Introduction

Cervical insufficiency (CI) is characterized by painless cervical shortening and dilation without uterine contractions, typically occurring in the second trimester of pregnancy, and leading to membrane prolapse, rupture, late miscarriage, or early preterm birth (PTB) [1–3]. Cervical insufficiency affects approximately 0.1–2% of pregnancies [2, 4–7], and is responsible for up to 20% of second-trimester miscarriages and PTBs [8]. However, its true prevalence is difficult to determine due to the lack of uniform diagnostic criteria [9, 10]. A short cervix, defined as a cervical length (CL) of ≤ 25 mm before 24 weeks of gestation, can indicate an ongoing CI process or be an independent risk factor for PTB [2, 11, 12]. Reported prevalence varies between 1–8% [13]. Transvaginal ultrasound assessment of CL is recommended during the second-trimester anomaly scan, performed 18–22 weeks of gestation, as a cervix measuring ≤ 15 mm is associated with a significantly increased risk of PTB [2, 5, 10, 11, 13, 14].

Multiple management strategies exist for CI and short cervix, including progesterone therapy, pessary placement, and cervical cerclage. Traditional cerclage indications include:

history-indicated: previous spontaneous second-trimester miscarriages or PTBs,

ultrasound-indicated: CL ≤ 25 mm before 24 weeks of gestation in women with a history of second-trimester miscarriage or PTB,

physical examination-indicated: advanced cervical dilation without symptoms or with membrane prolapse [2, 7, 10, 15–17].

While international guidelines agree on ultrasound- and physical examination-based cerclage indications, controversy remains regarding history-indicated procedures, particularly the number of prior second-trimester pregnancy losses and PTBs required for prophylactic intervention [3, 7]. Additionally, there is no consensus on the optimal CL threshold for cerclage placement in cases of short cervix, with some experts advising against cerclage in such cases [2, 10, 11, 13, 15, 16].

The objective of this study was to retrospectively assess pregnancy outcomes, defined by miscarriage rates and PTB rates before 32, 34, and 37 weeks of gestation, following history- and ultrasound-indicated cerclage procedures performed over a ten-year period at our center.

Material and methods

Study design

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at the Department of Obstertrics and Perinatology Jagiellonian University Collegium Medicum in Kraków, a tertiary healthcare center. The study included women with singleton pregnancies who underwent cervical cerclage placement and subsequently gave birth in our department between 2013–2023.

Cervical cerclage was performed based on one of the following indications:

history-indicated: at least one previous second-trimester miscarriage (14 0/7 to 21 6/7 weeks of gestation) or PTB (22 0/7 to 27 6/7 weeks of gestation) or prior cerclage placement in previous pregnancies,

ultrasound-indicated: CL ≤ 25 mm before 24 weeks of gestation, with or without a history of at least one second-trimester miscarriage or PTB before 34 weeks of gestation.

Data collection

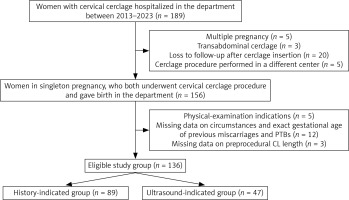

Participants were identified through a review of electronic and paper hospital records. Data extracted included maternal age, body mass index (BMI), history of hysteroscopy and dilation and curettage procedures, gravidity, parity, previous miscarriages and PTBs (with gestational age and delivery circumstances), and past cerclage placement. Additional parameters recorded for the index pregnancy included indication for cerclage procedure, gestational age at cerclage placement, shortest CL measurement, cervical dilation at admission, and follow-up outcomes such as gestational age at cerclage removal, gestational age at delivery, and neonatal birth weight. Women with multiple pregnancy, transabdominal cerclage, or physical examination indications for the procedure, as well as those lost to follow-up after cervical cerclage placement or who delivered in our department, but who had a cerclage procedure performed elsewhere, were not eligible for inclusion. Furthermore, cases with missing data on the circumstances of previous miscarriages and PTBs, as well as CL measurement prior to cerclage placement in the index pregnancy, could not be adequately categorized and were therefore excluded from the analysis. A detailed flow chart is presented in Figure 1.

Cervical cerclage procedure

All cerclages were placed in the operating theater by senior obstetricians using the McDonald technique and a braided polyester non-absorbable 5 mm tape. Procedures were performed with the patient in the lithotomy position, under spinal, rarely general, anaesthesia, and only after disinfection of vagina and cervix with antiseptic solutions. Periprocedural antibiotic prophylaxis consisted of 1 or 2 g (depending on the patient's weight) of cefazolin administered intravenously 30 minutes before the operation. Preprocedural vaginal and cervical cultures were not routinely performed, and even when they were, cerclage placement was not usually deferred to await its results. As for the timing of the procedure, history-indicated cerclages were typically inserted at around 14–16 weeks of gestation, whereas ultrasound-indicated cerclages were typically inserted up to 24 weeks of gestation. Asymptomatic patients were typically discharged 1–2 days after cerclage placement. Postprocedural ultrasound CL measurements were not performed as cerclage efficacy was assessed only by evaluating CL and dilation by digital examination. The cerclage was usually removed around 37 weeks of gestation or at the time of the scheduled caesarean section or earlier in cases of preterm premature rupture of membranes, labor onset, chorioamnionitis, or vaginal bleeding.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data were presented using means and standard deviations for variables that exhibited normal distribution and by medians and quartiles (Q1 and Q3) for skewed distributions. The χ2 test was employed for qualitative data, provided the assumption of an expected count of more than 5 in each cell was satisfied; otherwise, Fisher’s exact test was used. In cases where estimates could not be obtained due to table size for Fisher’s test, the Fisher-Freeman-Hamilton exact test was conducted. For continuous data, the normal distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Subsequently, the Student t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was applied for normally distributed or skewed data. Results with a p-value < 0.05 were deemed statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 29.0.2.0 (20).

Results

Study group characteristics

A total of 136 women met the inclusion criteria, of whom 89 (65.4%) underwent history-indicated cerclage, while 47 (34.6%) received ultrasound-indicated cerclage. There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of maternal age and BMI (p ≥ 0.05) (Table 1). However, women in the history-indicated group had a significantly higher number of previous pregnancies (p < 0.001), deliveries (p = 0.023), miscarriages (p = 0.004), second-trimester miscarriages (44.9% vs. 23.4%, p = 0.014), second-trimester PTBs (48.3% vs. 8.5%, p < 0.001), PTBs before 34 weeks of gestation (48.3% vs. 12.8%, p < 0.001), and previous cerclage procedures (28.1% vs. 10.6%, p = 0.020).

Table 1

Study group characteristics

Cervical cerclage – pre- and postprocedural characteristics

The median CL was significantly shorter in the ultrasound-indicated group than in the history-indicated group (15.0 mm vs. 33.9 mm, p < 0.001) (Table 2). The median gestational age at cerclage placement was 15.6 weeks for the history-indicated group and 22.0 weeks for the ultrasound-indicated group (p < 0.001). However, the median gestational age at cerclage removal did not differ significantly between the groups (37.7 weeks vs. 37.1 weeks, p = 0.097).

Table 2

Cervical cerclage – pre- and postprocedural characteristics

Pregnancy outcomes

The median gestational age at delivery was 38.4 weeks for history-indicated cerclage and 38.3 weeks for ultrasound-indicated cerclage (p = 0.728) (Table 3). Among the 136 pregnancies, there were four miscarriages (2.9%), 38 PTBs before 37 weeks of gestation (27.9%), and 94 term deliveries (69.1%). There were no statistically significant differences in miscarriage rates (3.4% vs. 2.1%, p = 0.999) or PTB rates before 32 (9.0% vs. 14.9%, p = 0.388), 34 (11.2% vs. 14.9%, p = 0.540), and 37 weeks of gestation (22.5% vs. 38.3%, p = 0.050) between the two groups. The median neonatal birth weight was comparable (3265 g vs. 3230 g, p = 0.648), and no neonatal deaths were reported.

Table 3

Pregnancy outcomes

Time between cerclage insertion, cerclage removal and delivery

The median time between cerclage insertion and removal was 154 days for the history-indicated group and 106 days for the ultrasound-indicated group (p < 0.001). Similarly, the median time from cerclage insertion to delivery was 158 days for history-indicated cerclage and 114 days for ultrasound-indicated cerclage (p < 0.001). The time interval between cerclage removal and delivery did not significantly differ between the groups (p = 0.233) (Table 4).

Table 4

Time between cerclage insertion, cerclage removal and delivery

Discussion

Cervical cerclage remains one of the most established interventions for preventing PTB in high-risk pregnancies [18]. However, the optimal criteria for its application, particularly regarding history-indicated procedures, continue to be debated. International recommendations on the use of cervical cerclage vary significantly. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists advocates for history-indicated cerclage in cases of at least one previous second-trimester miscarriage or PTB [10]. In contrast, other organizations, such as the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada, and the Polish Society of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (PTGiP), suggest stricter criteria, requiring at least three prior second-trimester pregnancy losses or PTBs before recommending a prophylactic cerclage procedure [15–17] (Table 5). Notably, the PTGiP guidelines were published shortly after the conclusion of our study [2]. A fundamental issue in history-indicated cerclage is the relatively high probability of term delivery even in women with prior PTBs. Studies have shown that approximately 85% of women with a history of one spontaneous PTB will carry their subsequent pregnancy to term, and even among those with two prior PTBs, around 70% will deliver at term [19–21]. Consequently, some researchers argue that obstetric history alone may not be a sufficiently strong predictor for adverse pregnancy outcomes [20]. This is further supported by epidemiological data showing that up to 85% of preterm deliveries occur in women without a prior PTB history [13]. Despite these considerations, our study found that only 2.2% of women in the history-indicated group met the strict criterion of at least three prior second-trimester miscarriages or PTBs (data not shown). This low prevalence makes it challenging to conduct large-scale prospective studies assessing the benefit of cerclage in such cases. Previous studies have attempted to compare outcomes between women with one vs. at least two prior PTBs, showing slightly better results in the former group, with a potential tendency for later gestational age at delivery and lower PTB rates [3–5, 8, 9, 22].

Table 5

Comparison of recommendations on cervical cerclage in singleton pregnancy

| Society | Year | History-indicated cervical cerclage | Ultrasound-indicated cervical cerclage | Short cervix |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACOG [10] | 2014 | At least one previous second-trimester pregnancy loss or cervical cerclage in prior pregnancy | At least one prior PTB before 34 weeks of gestation and CL < 25 mm before 24 weeks of gestation | Not recommended |

| SOGC [17] | 2019 | At least three previous second-trimester pregnancy losses or extreme PTBs | At least one prior PTB or possible CI and CL ≤ 25 mm before 24 weeks of gestation | Not recommended |

| FIGO [16] | 2021 | At least three previous PTBs and/or mid-trimester losses | At least one prior PTB and/or mid-trimester pregnancy loss and CL < 25 mm before 24 weeks of gestation | Can be considered on an individual case basis in high-risk women |

| RCOG [15] | 2022 | At least three previous PTBs | At least one prior second-trimester pregnancy loss or PTB and CL ≤ 25 mm before 24 weeks of gestation | Only in presence of other risk factors for PTB |

| PTGiP [2] | 2024 | At least three previous miscarriages over 16 weeks of gestation or PTBs before 34 weeks of gestation or previous pregnancy with advanced CI and amniotic membranes protrusion | At least one previous miscarriage over 16 weeks of gestation or PTB before 34 weeks of gestation and CL ≤ 25 mm before 24 weeks of gestation | Can be considered in case of CL less than 15 mm amid progesterone therapy failure to retain CL between 25 and 15 mm |

[i] ACOG – American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, CI – cervical insufficiency, CL – cervical length, FIGO – International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, PTB – preterm birth, PTGiP – Polish Society of Gynecologists and Obstetricians, RCOG – Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, SOGC – Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada

Another standard indication for cerclage placement is an ultrasound-diagnosed short cervix (CL ≤ 25 mm) before 24 weeks of gestation in women with a history of at least one second-trimester pregnancy loss or PTB (Table 5). However, significant discrepancies exist between guidelines regarding the management of women with a short cervix but no history of PTB (Table 5). A meta-analysis by Berghella et al. [23] suggested no overall benefit from cerclage in women with CL < 25 mm, except in a subgroup with CL ≤ 10 mm, where cerclage reduced PTB rates before 35 weeks of gestation (RR = 0.68; 95% CI: 0.47–0.98). In our study, cerclage was performed in cases where cervical shortening progressed despite progesterone therapy or in women with previously undiagnosed CL ≤ 15 mm. These cases (n = 31) were analyzed alongside classic ultrasound-indicated cerclages (n = 16), yielding a total of 47 cases. No statistically significant differences were found between these subgroups in terms of miscarriage rates, PTB rates at different gestational thresholds, or gestational age at delivery (data not shown). Previous studies have also reported highly variable PTB rates before 37 weeks of gestation in ultrasound-indicated cerclage cases, ranging from 17.1% [4] to 54.2% [5]. Differences in inclusion criteria likely contribute to these discrepancies. While some studies included all women with cervical shortening [4, 9], others restricted their analysis to those with prior PTBs [5, 8]. Despite this heterogeneity, our study’s findings align with or exceed the outcomes reported in these studies, suggesting that a selective approach to cerclage may be appropriate.

One of the key takeaways from this study is that pregnancy outcomes do not differ significantly between history-indicated and ultrasound-indicated cerclage groups. These results align with previous research [4, 5,8, 9, 22] (Table 3). Given this evidence, the clinical focus should shift from primarily performing prophylactic cerclage towards a more individualized approach based on systematic CL monitoring. The predominance of history-indicated cerclage in clinical practice (65.4% in our study) highlights the tendency toward prophylactic intervention despite the increasing recognition of CL screening as a reliable alternative. Prophylactic cerclage, typically performed in the late first or early second trimester, has a low risk of complications [6] and is often preferred by both obstetricians and patients due to anxiety surrounding prior pregnancy loss [24]. However, the reliance on history alone may lead to unnecessary interventions. A meta-analysis by Berghella et al. [25] demonstrated that most women with a prior PTB do not develop cervical shortening in subsequent pregnancies, further supporting a more selective approach. Moreover, the inherent biases in comparative studies must be considered. Pereira et al. [26] described cervical changes as a continuum, with only a subset of women progressing from a normal cervix to cervical shortening and, eventually, PTB. Performing cerclage in women with an anatomically intact cervix may artificially inflate its perceived benefit, as many of these women would have delivered at term without intervention [9]. Additionally, inconsistent documentation of prior miscarriages and PTBs may lead to CI overdiagnosis and unnecessary cerclage placement.

Strengths and limitations

This study’s strengths include a rigorous review of cerclage procedures performed over a decade in a tertiary referral center. The strict inclusion criteria for history-indicated cerclage also ensured a focus on cases highly suggestive of CI. The observed median gestational age at delivery (38.4 weeks in the history-indicated group and 38.3 weeks in the ultrasound-indicated group) confirms the effectiveness of cervical cerclage in prolonging pregnancy without introducing additional maternal or neonatal risks. However, limitations include its single-center and retrospective design. Missing data on prior preterm deliveries limited the ability to precisely classify some cases, introducing potential selection bias. Additionally, some women who underwent cerclage at our institution but delivered elsewhere were lost to follow-up. Future studies should aim to refine history-based indications for cerclage and evaluate pregnancy outcomes following physical examination-indicated cerclage in a larger and more diverse cohort.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that pregnancy outcomes following history-indicated cervical cerclage are comparable to those of ultrasound-indicated procedures, with no statistically significant differences in miscarriage rates or PTB rates before 32, 34, and 37 weeks of gestation. These findings provide further evidence that cervical cerclage is an effective intervention for prolonging pregnancy and enabling women with CI to reach term. Given the comparable efficacy of both history-indicated and ultrasound-indicated approaches, it is recommended that clinical practice prioritize systematic CL screening and adopt a more selective approach to cerclage placement, reserving the procedure for those cases where it is most likely to provide benefit, rather than routinely performing prophylactic cerclage procedures.