Introduction

Bladder cancer is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers worldwide and stands as a prevalent cause of death [1, 2]. About 80% of bladder cancer s are diagnosed at the stage of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) [3], which is generally associated with a good prognosis, given that patients adhere to strict cystoscopic surveillance and transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURB) [4, 5]. However, a certain proportion of cases progress to muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC), where cystectomy is a treatment of choice. Although TURB and cystoscopies are regarded as minimally invasive procedures, patients who endure these interventions repeatedly are put at risk of certain procedural complications, which include urinary tract infections and bladder perforation among others. Those kinds of procedures also are related to substantial healthcare costs. Therefore, new prognostic modalities are needed to decrease patient burden and optimize the use of healthcare resources.

For the time being, clinical as well as morphologic and histologic tumour features, are the leading determinants of the intensity of cystoscopic surveillance after TURB for NMIBC [6, 7]. However, many trials which aimed to develop new prognostic modalities for NMIBC follow-up optimization, have failed to present any improvement in terms of stratifying the risk of possible recurrence or progression of non-muscle invasive tumours [8, 9]. Therefore, the main purpose of this study was to evaluate prognostic capabilities of series of blood count derived biomarkers as well as nutritional risk scores, for predicting recurrence or progression after TURB for NMIBC. Furthermore, an additional aim was to verify whether inflammatory biomarkers improve the prognostic properties of European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) risk scores.

The investigated biomarkers included the following neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), derived NLR (dNLR), modified Glasgow prognostic score (mGPS) and prognostic nutritional index (PNI).

Material and methods

The study is a post hoc analysis of a prospective observational pilot study. The approval of the Bioethical Committee of the Wroclaw Medical University was obtained (approval number: KB-692/2019; Ethical Statement Date: 22 October 2019, Wrocław). The informed consent form (ICF) was obtained from each participant. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was funded by a research grant of the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (grant number: 0073/DIA/2019/48). The whole study database is available in an open-source repository under DOI: 10.17632/65p8fnnf8d.1.

The primary aim of the study was to assess an array of novel biomarkers as predictors of poor oncologic outcome after TURB for NMIBC. Due to paucity of clinical data in this topic, no sample size calculation was performed. The secondary aim, discussed in this paper, was to evaluate complete blood count (CBC) biomarkers (NLR, MLR, PLR, dNLR) and three nutritional markers (GPS, mGPS, PNI) in the same clinical context.

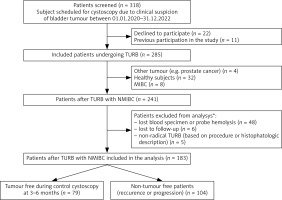

Between 01.01.2020 and 31.12.2022, all patients with a clinical suspicion of bladder tumour visiting the Urology Outpatient Clinic of the Wroclaw Medical University Hospital were screened for eligibility using prespecified criteria. The criteria are described in the National Clinical Trial (NCT) registration number: NCT06235853. 318 subjects were deemed to be potentially eligible. After obtaining ICF a total of 285 patients were included in the study. The flowchart of the screening and enrolment process is presented in Figure 1.

Fig. 1

Flowchart of the enrolment process, follow-up and study workflow

MIBC – muscle-invasive bladder cancer, NMIBC – non-muscle invasive bladder cancer, TURB – transurethral resection of bladder tumour, * One patient was both lost to follow-up and had no specimens collected.

After inclusion, blood samples were drawn from each patient before their visit in the Outpatient Urology Clinic. A hospital admission to perform cystoscopy (and possibly TURB) was made if deemed indicated by the attending physician. The blood samples were drawn and a dedicated laboratory panel was performed. During hospitalization, cystoscopy and/or TURB was carried out as appropriate. Surgical data was gathered using the procedure report. After completion of endoscopic treatment all necessary data was collected and the described biomarkers were calculated.

All patients underwent a control cystoscopy, which timing was at the discretion of the treating physician. In cases of evident or suspected disease recurrence, patients were qualified for TURB. If the patients changed the treating centre or did not show up for their control visits, follow-up by means of telephone contact was attempted. The decision to introduce Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) treatment or intravesical chemotherapy was made on a case-by-case basis by the treating physician.

The main outcome was the occurrence of oncological events, namely the composite of the recurrence of NMIBC and the progression of NMIBC to MIBC during the first surveillance cystoscopy.

The following biomarkers derived from laboratory blood works and three nutritional risk scores, were investigated using the given:

Glasgow prognostic score and mGPS are calculated using C-reactive protein (CRP) and albumin levels. Considering GPS, patients with elevated levels of CRP (> 1 mg/dl) and hypoalbuminemia (< 3.5 g/dl) are given 2 points, patients with elevated CRP (> 1 mg/dl) or hypoalbuminemia (< 3.5 g/dl) are allocated a score of 1, whereas patients within normal levels are allocated 0 points [10]. The modified GPS demonstrates elevated inflammatory biomarkers as follows: patients with CRP levels above 1 mg/dl and hypoalbuminemia are allocated 2 points, patients with elevated CRP levels (> 1 mg/dl) are given 1 point and patients with normal CRP levels are allocated 0 points (≤ 1 mg/dl) [11].

Mean standard deviation or median and interquartile ranges were used to present non-binary data. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to evaluate the distribution of the data. Categorical data were expressed in terms of numbers and percentages. To compare categorical data, χ2 or Fisher’s exact test was conducted. The Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test was implemented to evaluate the statistical significance of differences in continuous data according to the data distribution. Receiver operator curves (ROC) were generated to assess the predictive value of the investigated biomarkers. The area under the curve (AUC) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), specificity, sensitivity, Youden’s point with the best cut-off value was calculated for each ROC curve. Spearman’s rank correlation (due to skewed data distribution) was employed to examine the correlations between continuous data. A two-tailed p-value of < 0.05 was statistically significant. To perform all analyses Statistica Software version 13.2 (StatSoft, Tulsa, Oklahoma, United States) was used.

The study was retrospectively registered in the Clinicaltrials.gov, with registration number NCT06235853. Due to the pilot character of the study no sample size calculation was performed. The test power for the most robust findings was calculated retrospectively using JMP Pro software.

Results

A total of 318 patients were screened for eligibility and 241 were deemed potentially eligible. After excluding cases of screening failure, lost laboratory specimens, specimen haemolysis and patients who were lost to follow-up, a final group of 183 patients with complete dataset was analysed. Figure 1 presents the enrolment process.

The patients were divided into two groups according to whether they were tumour free during the initial follow-up (n = 79) – Group 1 (classified by either cystoscopy with cytology or histopathology result of subsequent TURB), and those in whom tumour recurrence occurred or cancer progression to MIBC was documented during the follow-up period (n = 104) – Group 2. The median time to first surveillance cystoscopy after primary TURB was 94 days. A demographic description along with levels of investigated biomarkers is shown in Table 1. Restaging TURB (reTURB) was performed in 4 cases in Group 1 and in 9 cases in Group 2. After primary TURB, 9 and 12 BCG-naive patients in Group 1 and Group 2 had BCG therapy prescribed, respectively. In most cases where BCG or intravesical therapy was initiated before TURB, it was continued except for 3 subjects with poor treatment tolerance.

Table 1

Characteristics of the whole study population and study subgroups with investigated biomarker levels

[i] BCG – Bacillus Calmette-Guérin, dNLR – derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, CCI – Charlson comorbidity index, CIS – carcinoma in situ, EORTC – European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, GPS – Glasgow prognostic score, IQR – interquartile ranges, mGPS – modified Glasgow prognostic score, MLR – monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio, NLR – neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, PLR – platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, PNI – prognostic nutritional index

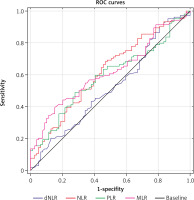

The analysed markers have shown poor predictive value for prognosing recurrence and progression of NMIBC after TURB. Table 2 presents the results of ROC analysis, where NLR showed the highest AUC of 0.618 (95% CI: 0.536–0.699). Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio > 1.5 can predict the study outcome with 90% sensitivity and 19% specificity. The odds ratio for predicting the main study outcome was 1.46 (95% CI: 1.104–1.921) with p < 0.0001. All of the generated ROC curves are presented in Figure 2. Among nutritional indexes, none has predicted disease progression or recurrence. The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer recurrence points predicted the composite study outcome with AUC of 0.804 (95% CI: 0.740–0.868). To evaluate the combined impact of nutritional risk scores and blood count based systemic inflammatory biomarkers along with EORTC points score, we have employed logistic regression analysis and tested both recurrence and progression point with each investigated parameter in a bivariable model analysis as shown in Table 3. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, MLR and dNLR consistently contributed to improving models’ diagnostic performance for EORTC recurrence and progression points. Similarly, to the univariable ROC curve analysis, GPS, mGPS and PNI did not significantly contribute to increasing the predicting capability of bivariable models.

Table 2

Characteristics of receiver operator curves for predicting the study outcome

[i] AUC – area under the curve, CI – confidence intervals, dNLR – derived neutrophile-to-leukocyte ratio, EORTC – European Organization for Research and Treat-ment of Cancer, (m)GPS – (modified) Glasgow prognostication score, MLR – monocyte-to-leukocyte ratio, NLR – neutrophile-to-lymphocyte ratio, PLR – platelets-to-leukocyte ratio, PNI – prognostic nutritional index, SE – standard error

Table 3

Bivariable logistic regression model analysis for predicting the study outcome

[i] AUC – area under the curve, CI – confidence intervals, dNLR – derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, EORTC – European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, GPS – Glasgow prognostic score, mGPS – modified Glasgow prognostic score, MLR – monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio, N/A – not available,

Fig. 2

Receiver operator curves of complete blood count biomarkers for predicting the study outcome

dNLR – derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, MLR – monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio, NLR – neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, PLR – platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, ROC – receiver operator curves

As NLR has shown the most robust performance among all investigated biomarkers we have also aimed to assess any possible correlation with tumour histology. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio values among study patient subgroups have been presented in Table 4. No statistically significant differences were found between subgroups.

Table 4

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio values according to the study outcomes and primary tumour histology

Discussion

Based on the analysis of generated ROC curves we suggest that NLR > 1.5 may serve as an ancillary screening biomarker for patients with NMIBC undergoing TURB, for prognostication of poor oncologic outcome. At the given cut-off it can detect patients with poor outcome after transurethral tumour resection with 90% sensitivity and 19% specificity. In our analysis MLR showed similar performance compared to NLR, with AUC of 0.617. Both NLR and MLR were predictive for poor outcome, independently from EORTC risk score. The remaining blood count biomarkers showed lower prognostic value than NLR and MLR. The analysed nutritional biomarkers also failed to predict NMIBC progression or recurrence 3 months post TURB. No association between analysed biomarker levels and tumour histology has been found.

According to the literature, systemic inflammatory response biomarkers such as NLR, PLR and dNLR, are able to predict detrimental outcomes in a number of pathologies [12–14], including various cancer types [15 ,16]. For instance, elevated NLR and PLR were inversely correlated with overall survival and progression-free survival in patients with metastatic small cell lung carcinoma who were treated with nivolumab [17]. Analogous correlation has been presented among others in colorectal cancer [18], breast cancer [19], head and neck cancers [20] or prostate cancer [21]. However in case of prostate cancer, some reports indicate that among inflammatory biomarkers, MLR is the strongest predictor of outcomes, outperforming both NLR and PLR [22].

Our study has shown that NLR can be predictive for event-free survival (EFS) in patients with NMIBC treated with TURB and achieved a low AUC of 0.618. A recent meta-analysis revealed that NLR is also predictive of recurrence and progression of NMIBC [23]. However, the cited meta-analysis also reports high inter-study heterogeneity and included only retrospective studies. Our results are also coherent with a study conducted by Araujo et al. on a vast cohort of breast cancer patients, where it yielded AUC of 0.64 for prediction of EFS [24].

When it comes to investigated nutritional scores, none of them has presented prognostic capabilities in terms of prognostication in the discussed clinical scenario in our study. Available literature suggests that the investigated biomarkers mainly predict oncologic disease outcomes in more advanced or metastatic stages [25, 26]. Furthermore, its impact may also be significant in cases where major surgery is a part of oncologic treatment as in cases of gastric cancer, renal cell carcinoma or cancers treated with hepaticojejunostomy [27–29]. This may be associated with the fact that PNI is predictive of postoperative acute kidney injury, wound infection, stroke and perioperative mortality [30, 31]. The available studies that investigated PNI in the setting of NMIBC showed conflicting results. This parameter could improve prognostic accuracy of other risk scores, however its benefit was found to be marginal [32]. On the other hand, some studies have shown a significant correlation of PNI and GPS with recurrence-free survival in patients with NMIBC [33, 34].

According to the EAU 2024 Guidelines on NMIBC, many biomarkers have been tested for diagnosis and follow-up. None of them is recommended for identifying or predicting recurrence or progression. Although some biomarkers may be useful in determining whether to perform cystoscopy in the diagnostic process and recognizing patients at risk of recurrence or progression (especially in the high-risk group), the financial costs of these assays often exceed the ones of cystoscopy [35]. Therefore, cheap and cost-effective markers are still needed to tailor individualized therapy and follow-up.

Based on the literature, CBC biomarkers can be applied for prognostication with acceptable results in patients with locally advanced and/or metastatic cancers. In less advanced disease (as presented in our study on NMIBC patients and in a study by Araujo et al. [24] its impact on prognostication remains poor. We therefore hypothesize that only more advanced tumours have enough impact on immunological and hematopoietic system, to present with clinically important changes in CBC measurements, which may be prognostic of the disease course. Similarly nutritional prognostic indices as PNI and mGPS present the best prognostic utility for advanced neoplastic disease where nutritional deterioration is predictive of postoperative adverse events and worse response to immunotherapy or chemotherapy.

Regarding EORTC risk score, some studies showed that NLR can increase its predictive properties [36, 37]. The available literature does not provide any data on the correlation between EORTC scoring model and other CBC biomarkers, except for a study by Avcı et al. in which PLR and De Ritis ratio were analysed [38]. However, it did not demonstrate prognostic value for PLR.

Limitations of this study

The study we have performed has several limitations. First, the patient group remains relatively low. The retrospectively calculated test power for comparison of NLR (being the most robust biomarker) between groups was 75.9% making the study almost adequately powered. Second, the observation time was short. However, considering high recurrence rates, the group was well balanced in terms of event distribution. The strengths of our study include its prospective character as most of the scientific reports on the discussed topic are retrospective studies. Furthermore, the study group was a real-world heterogenous population since it included patients with primary and recurrent tumours, patients with previous BCG therapy and intravesical chemotherapy. On one hand, such heterogeneity may negatively impact the robustness of our findings but on the other, it increases generalizability of the results.

Conclusions

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and other CBC biomarkers can be predictive of recurrence or progression in patients with NMIBC treated with TURB, however their contribution to clinical practice remains insufficient. Prognostic nutritional index and modified GPS have no prognostic value for risk assessment in this patient group. However, CBC biomarkers might be a useful, economic and accessible diagnostic tool that enhances EORTC prognostic values.