Introduction

The use of contraceptives is a key public health strategy, as it allows women to control their reproductive health, prevent unintended pregnancies, and actively participate in family planning. The availability and access to these methods not only improve maternal and child health outcomes but also help reduce unintended pregnancies, contributing to fewer induced abortions and the prevention of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV [1]. Moreover, the proper and consistent use of contraceptive methods promotes women’s autonomy, enhances their quality of life, and facilitates the economic and social development of communities [2].

However, one of the most important and often underestimated groups regarding contraceptive use is women of advanced reproductive age. Although fertility decreases with age, the risk of unintended pregnancy persists due to ongoing sexual activity and residual fertility in these women. The lack of effective contraceptive use in this age group can result in unintended pregnancies, with both physiological and social consequences. Women over 40 years of age face a higher risk of obstetric complications, such as miscarriage, chromosomal abnormalities, preeclampsia, and postpartum hemorrhage, making the use of contraceptive methods even more important at this stage [3–5].

Contraceptive use must be understood as a multifactorial construct influenced by health system factors – coverage, provision, availability, and public policies – as well as by individual factors of sociodemographic, cultural, educational, and economic nature [6]. Globally, only 16.03% of women aged 40 to 49 use some form of contraception, according to United Nations data; while in Peru, this figure rises to 22.55% [7]. Indeed, actions to ensure women’s sexual and reproductive health are mainly focused on younger women, creating an unmet need for family planning among older women and neglecting the impact that limited visibility and inaction have on their well-being and that of their on those around them.

Among older women, the reproductive risks and the social and health implications of not using contraceptive methods are diverse. Healthcare providers must recognize that their approach should not focus solely on the decision and selection of a method, but also on the influence of the woman’s social environment and her personal preferences regarding childbearing intentions. Thus, it is necessary to promote a more comprehensive and accessible approach for this group, improve public health policies, and optimize care strategies to reduce unintended pregnancies and enhance maternal and perinatal health outcomes.

Thus, this study aimed to determine the prevalence and factors associated with contraceptive use among Peruvian women aged 40 to 49 years.

Materials and methods

Study design and data source

A quantitative, analytical, cross-sectional study was conducted based on the 2023 Peruvian Demographic and Health Survey (ENDES). This survey collects and records information on various health and demographic topics.

Sample size

ENDES participants were selected through stratified, cluster, random sampling. This study included women aged 40 to 49 who answered the question regarding current contraceptive use. Women who were pregnant at the time of the interview or who reported being in menopause were excluded. The final sample consisted of 5,347 women who met all the selection criteria.

Study variables

The analyzed variables were sociodemographic, gynecologic-obstetric and related to partner violence. The main variable was contraceptive use (referred to as “use of contraceptive methods” or “use of CMs” in the study), derived from variable V312 and dichotomized into current use (yes/no). Marital status was obtained from variable V501 and recategorized into two groups: “married or living with partner” and “never married, widowed, divorced, or not living with partner”. The number of live births came from variable V201 and was grouped into three categories: 0–2, 3–5, and 6 or more children. Knowledge of the ovulatory cycle was based on variable V217 and was considered correct only when the respondent answered “mid-cycle”; any other response was classified as a lack of knowledge. The desire to have more children was obtained from variable V602 and dichotomized between those who wanted more children and those who did not. Educational level was derived from V106 and grouped into three levels: no education or primary, secondary, and higher education. The variable “psychological or verbal violence” was created based on affirmative responses to variables D101A, D101F, D103A, D103B, and D103D, while “physical violence” was constructed with variables D106 and D107. Finally, the “total violence” variable considered the presence of any form of violence, including psychological, verbal, physical, or sexual violence.

Statistical analysis

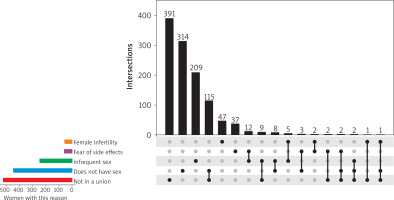

Databases containing the necessary variables were downloaded from the INEI web platform (https://proyectos.inei.gob.pe/microdatos/). Data processing was performed using STATA version 17. First, the databases were merged. We then used the svyset command to define the survey sampling structure, accounting for weighting factors, stratification, and clustering. Descriptive analysis reported absolute and relative weighted frequencies along with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The chi-square test was used to determine variable associations at a significance level of 0.05. Additionally, the RStudio 2024.12.1 software was used to produce a figure visualizing the reasons, individually and jointly, for not using contraceptives.

Results

A total of 5,347 women were included, with a weighted sample size of 6,886 adjusted for the complex survey design. Sociodemographic distribution showed that 60.25% were aged 40 to 44 years and 39.75% were aged 45 to 49 years. 35.38% were married or cohabiting. The majority resided in urban areas (81.46%), while 24.35% were employed. Regarding contraceptive use, 63.06% reported using some method. Statistically significant differences in contraceptive use were found according to age, with higher usage among women aged 40 to 44 years (p = 0.003), among married or cohabiting women (p < 0.001), unemployed women (p < 0.001), and rural residents (p < 0.001; Table 1).

Table 1

Sociodemographic characteristics of Peruvian women aged 40 to 49 years, ENDES 2023

Regarding gynecological-obstetric characteristics, 46.17% had 0–2 live births, 46.44% had 3–5, and 7.39% had 6 or more. Only 34.06% correctly knew the ovulatory cycle. 5.38% reported being visited by a health professional to discuss family planning, and 27.02% had a history of abortion. Additionally, 12.19% stated that they wanted more children. Regarding partner violence, 54.85% of women had experienced psychological or verbal violence, 31.85% physical violence, and 58.52% some form of violence. Statistically significant differences in contraceptive use were found according to the number of live births (higher among those with 3 to 5 children, p < 0.001) and among those who did not want more children (p < 0.001). Experiencing psychological or verbal violence (p < 0.001), physical violence (p < 0.001), or any form of partner violence (p < 0.001) was associated with lower contraceptive use (Table 2).

Table 2

Gynecologic obstetric characteristics of Peruvian women aged 40 to 49 years, by use of contraceptive methods, ENDES 2023

Among the group of women reporting contraceptive use, the most frequently used method was female sterilization (26.73%), followed by periodic abstinence (16.68%), and injectables (15.46%). Other methods included condoms (14.83%), withdrawal (9.84%), oral pills (8.05%), implants (2.63%), and other methods such as IUDs, male sterilization, and emergency contraception (5.78%). When grouping methods by type, 73.12% used modern methods, 26.52% used traditional methods, and 0.36% used folkloric methods (Table 3).

Table 3

Contraceptive methods used by Peruvian women aged 40 to 49 years, ENDES 2023

Among women not using contraceptive methods, 54.22% indicated that they intended to use them later, and 45.78% did not intend to use them. Among those expressing future intention to use contraceptives, the preferred methods were injectables (35.18%), condoms (21.43%), and implants (16.99%). Other methods mentioned included oral pills (12.29%), withdrawal (3.17%), female sterilization (2.72%), and others such as IUDs or emergency contraception (8.22%).

On the other hand, among women not planning to use contraceptive methods, the most frequent reasons were infrequent sexual activity (21.12%), female infertility (19.42%), not being in a union (18.42%), and the desire for more children (15.09%). Other reasons included fear of side effects (4.58%), menopause or hysterectomy (5.71%), health problems (3.57%), and other factors such as personal or religious opposition, partner’s infertility, or lack of access (12.09%) (Table 4).

Table 4

Intention to use contraceptive methods among Peruvian women aged 40 to 49 years, ENDES 2023

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the five most common reasons for non-use of contraceptives and their intersections with 18 additional reasons, resulting in a total of 23 possible reasons. The most frequent reasons included not being in a union, lack of sexual relations, infrequent sexual activity, fear of side effects, and perceived infertility – often reported in combination with other reasons. In the figure, black dots connected by lines represent specific combinations among the top five reasons, while black bars represent the frequency of intersections between these and the 18 additional reasons.

Discussion

The need for contraception in women over 40 is frequently overlooked, despite the continued risk of unintended pregnancy. Personal and environmental conditions influence decision-making regarding reproductive self-care, which can increase the risk of an unplanned pregnancy and, consequently, disrupt life plans or expectations during this stage of life.

Choosing the type of contraceptive method is important, as it must be adapted to the sexual and reproductive needs of each woman. In this study, the prevalence of contraceptive use (63.06%) was similar to that reported by Sothornwit et al. [8] (75.5%). Furthermore, the most commonly used methods were female sterilization and injectable contraceptives. This finding is consistent with other studies reporting that permanent methods were the most widely used [8], as well as with research indicating that most women used progestin-only hormonal contraceptives [9].

The reasons for not using contraceptive methods were diverse. Infrequent sexual activity was one of the main reasons, along with health problems, the desire to have children, and fear of side effects. These findings are in line with other studies, in which women over the age of 40 cited similar reasons [8]. In the decision-making process regarding contraception, the role of the partner is fundamental [10, 11]; indeed, one study indicated that husbands discouraged their wives from using modern methods due to fear of side effects [12].

It is important to highlight that reproductive responsibility often falls solely on women within couples. In the present study, among women intending to use contraception in the future, male sterilization was notably absent from the responses. In this regard, Burgin and Bailey [9] reported that although women in long-term relationships discussed vasectomy, most male partners strongly refused it. In this context, healthcare professionals should prioritize the involvement of both partners, providing evidence-based information to dispel misconceptions about contraceptives and promote shared decision-making regarding sexual and reproductive health.

This study identified sociodemographic factors associated with contraceptive use. Regarding age, a higher proportion of older women were found among those who did not use any method compared to those who did. Similarly, Godfrey et al. [13] demonstrated that hormonal contraceptive use decreases with increasing age.

Moreover, reducing gender inequality is crucial to improving access to family planning services and preventing violence. In this regard, Muluneh et al. [14] demonstrated that experiencing intimate partner violence is a determinant for non-use of contraceptives. These findings are consistent with our results, as women who had experienced violence were less likely to use contraception.

Additionally, previous studies have shown that a history of abortion in women over 40 years of age is significantly associated with the non-use of contraceptives, as is the number of children [8]. These findings were similar to those observed in the present study, where both factors were associated with contraceptive use. The reproductive history of women is a relevant aspect to understand their decision-making, as satisfaction with parity or traumatic experiences such as abortion can encourage reproductive self-care.

Takyi et al. [12] highlighted that contraceptive counseling favors a conscious and responsible method selection, where healthcare personnel play an active role. Nevertheless, our study found that a visit from a healthcare professional to provide family planning counseling was not associated with contraceptive use, highlighting potential missed opportunities for effective counseling and intervention.

Study limitations

This study has some limitations. First, response bias may have been present, as some variables were subjective, and self-reported data could not be verified. Second, social desirability bias could have led women to withhold information to protect their personal image. Third, given the cross-sectional nature of the study, causality between variables cannot be established. Additionally, the limited literature on contraceptive use among Peruvian women aged 40 to 49 restricts broader comparisons of the results. However, this limitation also represents a strength, as the study provides original evidence in a scarcely explored field. Moreover, the sampling method used in the national survey ensures representativeness, allowing the findings to be generalized to the population of Peruvian women in this age group.

Conclusions

The present study contributes novel evidence on contraceptive use in Peruvian women aged 40 to 49, a population often underrepresented in reproductive health research. The findings underscore the complexity of reproductive decision-making in midlife and call attention to overlooked opportunities for intervention.

Public health programs should prioritize equitable access to contraceptive counseling and work to shift the cultural norms that place disproportionate contraceptive responsibility on women. Developing gender-transformative approaches and enhancing healthcare provider training could help address persistent barriers. Further research is needed to evaluate tailored strategies that engage both partners and address contextual factors such as reproductive autonomy, aging, and social expectations.