Introduction

Hepatitis C remains a global health challenge, with an estimated 58 million individuals living with chronic infection as of 2019. The Eastern Mediterranean Region and the European region [1] exhibit the highest rates of infection worldwide.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) prevalence varies across European Union (EU)/European Economic Area (EEA) countries, with Italy, Romania, and Latvia being among those with the highest anti-HCV prevalence estimates. However, true prevalence rates across the EU/EEA are unknown due to the heterogeneity in HCV surveillance methods and coverage [2].

In 2020, the EU/EEA reported approx. 4.1 hepatitis C cases per 100,000 population, with Luxembourg and Latvia recording the highest rates at 58 and 36.2 cases per 100,000, respectively [3]. Notably, a screening-based study in Latvia found an anti-HCV prevalence of 2.4% [4], while psychiatric hospitals reported a higher prevalence of 6.8% [5]. Recognizing the global impact of hepatitis C, in 2016 all 53 countries in the WHO European region committed to eradicating viral hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030 [6].

Hepatitis C is a leading cause of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma [7], contributing to an estimated 290,000 deaths in 2019 according to the World Health Organization (WHO). The virus primarily spreads through blood contact, with unsafe medical procedures, injectable narcotics, and transfusions of unscreened blood or blood products being common modes of transmission [1]. Within the EU/EEA Member States the leading mode of transmission is use of injectable narcotics followed by intercourse between men, and nosocomial causes [3]. While most modes of infection are unknown in Latvia, some are attributed to dental, other medical [8] and cosmetic procedures [9].

Long-term assisted living facilities (LTALF) provide procedures that can lead to bloodborne pathogen transmission when infection control measures are not conducted. Some of the procedures are phlebotomy, podiatric, nail care and glucose monitoring [10, 11]. These procedures have been linked to 46 HCV outbreaks in long-term care facilities in the USA during the years 2008-2019. However, it is likely that this is only a fraction of the actual number of outbreaks [10]. Assisted living facilities, also known as group homes, have similar bloodborne pathogen transmission risk factors [10, 12].

Additionally, the homeless population, characterized by risk behaviours such as narcotic use [13-15] and prior incarceration [13, 16], has demonstrated a higher anti-HCV prevalence compared to the general population of the same region [14, 17, 18]. Residents in long-term care facilities, group homes, and shelters are at risk of transmission through the sharing of personal items such as razors, toothbrushes, and nail clippers [19]. Understanding the prevalence and associated risks of HCV in these specific populations is crucial for developing targeted prevention and intervention strategies.

Material and methods

The retrospective study aimed to analyse data collected by HIV Prevention Point employees during their routine work over a two-year period from October 1, 2020 to October 31, 2022. The screening was conducted in shelters and LTALF. Some shelters operated only as overnight stays, while others provided full-time shelter during the colder months. In this study, LTALF include group homes and social care centres, also known as nursing homes. In both types of LTALF, residents live there long term, share common spaces, and receive assistance with daily activities. The main difference is that social care centres provide 24/7 assistance, while group home residents have usually a more independent lifestyle. The screening, which was offered free of charge, involved 46 LTALF and 6 shelters randomly selected from the social service providers register of Latvia. The register can change as facilities are added or removed; therefore, only an estimate can be provided. Currently, there are 25 shelters and 324 LTALF in the register. The register only includes information about the maximum number of residents who can reside at a facility. The cumulative capacity for shelters is 451, and for LTALF, it is 21,796. To ensure the list remained unchanged during facility selection, it was used only as a downloaded file, then the facilities were contacted in alphabetical order.

The screening utilized HCV rapid plasma immunochromatographic qualitative antibody tests provided by the Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (CDPC) of Latvia. The tests were conducted by HIV Prevention Point employees who had undergone specialized five-hour training from the CDPC of Latvia. This training covered safe testing procedures, proper disposal of medical waste, and accurate interpretation of rapid immunochromatographic test results. Employees also learned how to conduct interviews to gather information about risk factors. The training included both theoretical and practical sessions and was led by a senior HIV Prevention Point employee with over 10 years of experience.

To ensure accuracy and reliability, all procedures strictly followed the test manufacturer’s instructions. During testing, two employees were present to minimize distractions and ensure accurate result interpretation. Additionally, the CDPC checks the rapid tests used by HIV Prevention Points in Latvia annually or upon request, using blood samples from diagnosed patients provided by the Infectology Centre of Latvia. Whilst conducting an HCV rapid test the participants were asked questions concerning demographic and risk factors such as sexual activity, intravenous narcotic use, and incarceration (Table 1). The interview was conducted in Latvian, Russian or English according to the participant’s preference. Every participant was asked the same set of questions. No identifying data were collected during the screening. Positive test results prompted a short consultation, informational leaflets, and a referral to a National Health Service compensated infectious disease specialist visit.

Table 1

Relationships between hepatitis C virus (HCV) risk behaviours, gender, and anti-HCV rapid test results and HCV prevalence among various population groups

Data, including test results and questionnaire responses, were recorded on a pre-developed paper form. The questionnaire was developed by the CDPC of Latvia for HIV Prevention Point use. Later the information was transferred to Google Sheets and Microsoft Excel, and statistically analysed using the program SPSS.

To determine the significance the chi-square (χ2) test was performed. Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s exact test was used to determine the p value. A significance level of p < 0.05 was used for statistical analysis. Negative confidence intervals were considered not applicable due to the small size of the population exhibiting some risk factors. To ensure proper statistical analysis, consultation on the appropriate methodology was sought from the Riga Stradins University’s Statistics Unit.

The interview-based data collection method and assurance of participant anonymity created conditions where there were no missing data.

This study was approved by Riga Stradins University Ethics committee.

Results

2838 tests were done by HIV Prevention Point employees during their routine work in LTALF and 349 in shelters. In LTALF 118 (4.2%; 95% CI: 0.3-0.5%) tests showed presence of HCV antibodies and 42 (12.0%; 95% CI: 0.09-0.15%) in shelters.

The mean age of subjects in LTALF was 55.5 (range 5-102 years) and in shelters 49.5 (range 31-67 years). However, the mean age of subjects whose tests were positive for anti-HCV was 53.1 (range 28-85) and in shelters 51.8 (range 31-67). In LTALF 49% of the tested persons were men and 51% women. In shelters 84% were men and 16% women.

10.1% of LTALF residents noted that they had been sexually active in the last 12 months, 5.6% admitted incarceration, and 1.2% intravenous (IV) narcotic use. In shelters 32.7% had been sexually active during the last 12 months, 26.9% admitted incarceration, and 6.8% IV narcotic use. Of those with a positive anti-HCV test in LTALF, 12.7% had a history of IV narcotic use (p < 0.001), 22.9% had been incarcerated (p < 0.001) and 91.5% did not use a condom during their last intercourse (p = 0.024). In shelters in cases of a positive anti-HCV test 26.2% had a history of IV narcotic use (p < 0.001) and 54.8% had been incarcerated (p < 0.001). Other risk factors were not found to be statistically significant (Table 1).

Out of all the positive anti-HCV tests in LTALF 71.2% were administered to male participants and 28.8% to female participants (p < 0.001). In shelters 88.1% were administered to male and 11.9% to female participants (p = 0.436) (Table 1).

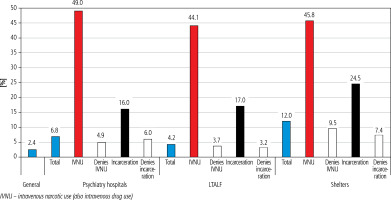

In both LTALF and shelters males had a higher anti-HCV prevalence, 6.0% and 12.6% respectively. In the female population the prevalence was 2.3% in LTALF and 8.9% in shelters (Table 1). The prevalence among intravenous narcotic users was similar in both LTALF (44.1%) and shelters (45.8%). This was the highest prevalence amongst any of the statistically significant risk factor groups both in LTALF and shelters. The second highest prevalence in groups of statistically significant risk factors was amongst participants with incarceration history. In LTALF it was 17.0% and in shelters 24.5%. The prevalence amongst those who denied intravenous narcotic use was 3.4% in LTALF and 7.4% in shelters. In the group that denied prior incarceration the prevalence was 3.7% in LTALF and 9.5% in shelters (Table 1).

Discussion

The present retrospective study adds valuable insights into the anti-HCV prevalence in Latvia, particularly in underrepresented populations such as residents of long-term assisted living facilities (LTALF) and shelters. The existing limited prevalence studies in Latvia underscore the significance of the current investigation. Notably, the prevalence in LTALF (4.2%) is nearly twice that of the general population, providing a unique contribution to the understanding of HCV epidemiology in the country.

The only population-based study discovered a prevalence of 2.4%. However, children, prisoners and the homeless were not included [4]. Prevalence may vary in different populations. A screening study of Latvia’s psychiatric hospitals revealed a prevalence of 6.8% [5].

Studies have showed that anti-HCV prevalence is higher in the homeless population. A screening-based study in Dublin, Ireland discovered an anti-HCV prevalence of 37% in the homeless population [18]. In Sidney, Australia it was 29% [17]. A study conducted in Pennsylvania, USA discovered HCV antibodies in 4.6% of the homeless population [15], but in San Francisco and Minneapolis, USA it was 21.1% [14], and in Alameda, USA 25.5% [20].

The anti-HCV prevalence amongst LTALF varies. A study carried out in southern Italy reported a 2.8% anti-HCV prevalence amongst nursing home residents, which is lower than expected based on previous epidemiological studies [21]. At that time the anti-HCV prevalence in the general population was reported as 2.3% [22]. However, a more recent screening study done in Rome, Italy reported a prevalence of 4.4% [23]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of HCV infections in the elderly of long-term care settings found a pooled anti-HCV prevalence of 3.4%. However, the prevalence in the studies varied from 1.4% to 11.8%. Only 2 out of 6 studies had a significantly higher prevalence then the general population. It is important to note that the included data are not recent [24].

This screening study discovered in shelters an anti-HCV prevalence 5 times higher than that in Latvia’s general population [4]. While the prevalence in other research varies, all the discussed studies show that it is higher than amongst the general population [14, 15, 17, 18, 20]. However, such consensus is not seen amongst the LTALF population [21, 23, 24]. This study revealed a prevalence almost 2 times higher than that in the general population [4]. Amongst the participants who denied both or one of the two most significant risk factors the prevalence was lower than the total in the population, but it was still higher than that in the general population. This was found to be true in both LTALF and shelter populations (Table 1, Fig. 1).

Regarding the homeless population, the statistically significant risk factors found in this study echo those of others. Studies have found a significant association between HCV infection and intravenous narcotic use [13, 15] and incarceration [13, 25].

In the discussed LTALF studies only one study partially overlapped the risk factors that were researched in this study. The only overlapping risk factor was injection drug use. However, no significant association was found [26]. Although other LTALF studies investigated other risk factors or none [21, 23, 24], a study carried out in a senior centre found intravenous narcotic use to be significantly associated [27]. Also, in the general population intravenous narcotic use [20, 28] and prior incarceration [28] have been found to be associated with antibody prevalence. Both intravenous narcotic users and prisoners have been established as high-risk groups by the World Health Organization [16]. There was also a weak association (p = 0.024) between unprotected intercourse and anti-HCV prevalence. Although the chances of infection are lower, unprotected sex heightens the risk of infection [19, 29].

While in both LTALF and shelters there was a higher anti-HCV prevalence amongst men, the association was found to be significant only amongst LTALF residents. This finding does not completely correspond with other authors’ work. Other studies found no statistically significant gender associations amongst residents of long-term care facilities [21, 23, 24], although one study found an association with female gender [24]. As regards the homeless population, the results were mixed. An association was found with male gender [14, 20] or there was no significant association [15]. Likewise, in the general population the results show no association [30] or an association with male gender [4, 28].

This study has some limitations. It was not possible to have participant follow-ups. Participants with a positive test were given referrals and would receive compensated confirmatory testing. However, due to anonymity, we could not track how many participants used the referrals or the confirmatory tests results. Without follow-up data, we can only assess the prevalence of HCV, not its incidence. Additionally, it is impossible to determine the true impact of false-positive test results. Immunochromatographic anti-HCV tests are likely to have false positives [31]. There is a trade-off between diagnostic accuracy, costs, feasibility, and linkage to care. This could be mitigated by introducing point-of-care HCV RNA assays, which would enable a test-and-treat approach. This would be particularly beneficial in shelter populations, where there is a high risk of loss to follow-up [32]. We also note that, while the whole testing process was done anonymously, it is reasonable to assume that some participants answered untruthfully to sensitive questions, fearing information leakage, especially questions related to homosexuality, due to high stigma levels.

In Latvia, blood donors and pregnant woman get screened for anti-HCV. Anyone can use HIV Prevention Point services to get tested with an anti-HCV rapid test and receive consultations free of charge. Based on epidemiologic data, including early data from this screening, the Cabinet of Ministers issued a plan regarding HCV and other infectious diseases in Latvia. Closed off communities such as LTALF and shelter residents were recognised as high-risk populations. It is planned to expand screening in high-risk populations. However, no further specification of plans has been made.

A simplified service delivery model would provide the opportunity to diagnose, treat, and limit the spread of HCV more efficiently. Systematic HCV screening with rapid anti-HCV tests could be implemented in LTALF and shelters. Rapid anti-HCV tests are convenient and can be administered by non-specialist medical staff. Alternatively, a team of test conductors, as used in this study, could visit the facilities to conduct the tests. A test-and-treat approach could be implemented using HCV RNA assay tests, which would be especially beneficial for populations with low follow-up rates, such as the homeless.

Conclusions

The anti-HCV prevalence amongst residents of long-term assisted living facilities of Latvia is 4.2%, almost two times higher than in the general population. As regards the population of shelters, the prevalence is 12.0%, four times higher than in the general population. In both populations those who denied prior incarceration and/or intravenous narcotic use were also found to have a higher prevalence than in the general population. The statistically significant risk factors in both populations were intravenous narcotic use and prior incarceration. In the LTALF population unprotected sex and male gender were also significant risk factors. Both screened populations should be recognised as high-risk.

While the study acknowledges its limitations, such as potential false-positive results and challenges in obtaining participant follow-up data, it serves as a crucial foundation for future research and public health interventions.

The elevated prevalence rates in LTALF and shelters emphasize the urgency of targeted interventions in these high-risk groups. The identification of significant risk factors, including intravenous narcotic use and prior incarceration, underscores the importance of tailored prevention, screening and treatment strategies.