Introduction

Oral squamous cell cancer (OSCC) accounts for approximately 2–3% of all malignancies [1]. It is well established that this type of cancer is associated with a history of smoking and alcohol consumption [2]. Other risk factors include improper dental hygiene, genetics, and human papilloma virus (HPV) infection, which is typically associated with oropharyngeal cancer, but its role in oral cancer is not well understood [3]. Despite advances in diagnostics and therapy the mortality rate of OSCC remains high at about 50% [4]. There are several tumour prognostic factors that influence treatment outcome, including the stage of the disease, perineural/vascular invasion, extranodal extension, and margin status [5]. Attention is being paid to biomarkers that would allow for early diagnosis and thus better treatment outcomes. Cancer biomarkers are molecular indicators of cancer risk and oncological activity of the disease. The clinical application of biomarkers is broad. They can also be used for screening, predicting response to treatment, and monitoring response after treatment. There is an increasing focus on precision oncology in the development of targeted therapies because they are only effective in patients with specific cancer mutations. Biomarkers are then the tools used to identify these subgroups of patients [6]. In head and neck, prognostic molecular biomarkers are not yet approved for clinical application, mainly due to conflicting results; therefore, ongoing research is underway to provide more real-world data. One of those factors is HPV status, which is in daily use in oropharyngeal cancer (HPV-related tumours have better prognosis) [7]. In oral cancer mandatory tests have not been performed; therefore, the incidence of HPV in oral cancer is unknown and ranges between 2 and 43% [8]. With such a wide range of results, it is difficult to assess its impact on prognosis. Another biomarker being widely discussed in head and neck cancer in recent years is the status of programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1). Programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) is a key inhibitory receptor that regulates central and peripheral T-cell tolerance. In tumour cells the upregulation of PD-L1 leads to immune escape [9]. The prognostic value of PD-L1 positivity in oncology is inconsistent. Most of the studies (dealing with oeso-phageal and lung cancer) reveal worse outcomes, whereas favourable outcomes have been observed in PD-L1-positive cancers in melanoma and colon cancer [10–13].

The aim of our study was to determine the true HPV and PD-L1 status in oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma and their influence on patients’ outcomes.

Material and methods

This was a case-control retrospective study of 68 adult patients treated surgically for primary OSCC from 2018 to 2022 at the Department of Head and Neck Surgery, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, The Greater Poland Cancer Centre. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, approval from the Ethics Committee was not required.

Patients who underwent surgery for OSCC (with fresh tumour tissue that was immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C) during the study period were included, except for those who met any of the following exclusion criteria: recurrent OSCC (12 patients); second primary malignancy (3 patients); synchronous primary malignancy; follow-up of < 24 months (unless recurrence or death occurred earlier; 5 patients); and primary treatment other than surgery (4 patients).

Evaluation of the following variables was done: demographics (age, sex, smoking status), and pathologic factors (T stage; N stage; disease stage; primary tumour margin status; perineural invasion [PNI]; lymphovascular invasion [LVI]; extranodal extension [ENE]; and adjuvant treatment [radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy]).

All patients underwent surgical resection (en bloc intent) with a macroscopically-free (1 cm) tumour margin resection. Based on the patient’s preoperative tumour stage and diagnostic evaluation, simultaneous neck dissection was carried out when indicated.

Tumours were staged according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). Recurrences were documented based on clinical, histopathological, and/or radiological examination. Failure was classified as local, regional, or distant. New tumours located ≥ 2 cm from the primary tumour were classified as second primary tumours. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the time elapsed (in months) from the date of surgery until recurrence. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from the date of surgery to the last follow-up or death.

Samples were immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C until RNA isolation. The procedures were approved by the Local Ethical Committee of Poznan University of Medical Sciences (Protocol code 452/20, date of approval 17 June 2020).

RNA isolation, reverse transcription, and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis

Total RNA was isolated from tissues using an RNA purification kit (RNeasy Mini Kit, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA samples were quantified by spectrometric measurement and qualified by gel electrophoresis. Subsequently, the samples were reverse-transcribed into cDNA with the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), using 500 ng of total RNA. qPCR was carried out with the CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using PowerTrack SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and primers specific for the PD-L1 gene (forward primer GGACAAGCAGTGACCATCAAG, reverse primer CCCAGAATTACCAAGTGAGTCCT). The PD-L1 gene expression level was normalised to SDHA (succinate dehydrogenase complex flavoprotein subunit A) gene, and the relative expression level was determined by the Pfaffl method. The calibrator was prepared as a mixture of the patients’ cDNA, and successive dilutions were used to create a standard curve to evaluate the efficiency rate of each primer. The primer sequences used in this study are listed in Supplementary File S1. Upon review, the ΔΔCq values obtained from qPCR approximated log-normal distribution, which is why the values were log10-transformed prior to analysis. After log-transformation, the data followed a normal distribution (assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test).

Statistical analysis

The normality of the observed patients’ data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The difference between 2 groups was assessed with Students’ t test (if data followed normal distribution) or with the U Mann-Whitney test (if data did not follow a normal distribution). The difference between more than 2 groups was estimated with one-way ANOVA (if data followed the normal distribution) or Kruskal-Wallis’ test (if data did not follow the normal distribution).

The correlation between the studied variables was determined using Spearman’s rank correlation. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 10 software, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The patient survival analyses were estimated using the Kaplan- Meier method. We used Cox proportional hazard regression analysis to assess how continuous data impacts survival. The optimal cutoff points of expression differentiating patients based on survival were determined using the Cutoff Finder [14]. In all graphs, p ≤ 0.05 is marked as *, p ≤ 0.01 is marked as **, p ≤ 0.001 is marked as ***, p ≤ 0.0001 is marked as ****, and not significant is marked as ns.

Results

The analysis included 44 patients with a mean age of 61 years (range 26–90), mostly males (n = 30, 68%). About half of the patients were treated in early local stage disease (T1–2, n = 21; 47%), with 25 pts (60%) treated with no neck disease. Clinical and demographic characteristics of the group are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

PD-L1 gene expression of oral tongue tumours stratified by clinical characteristics

HPV E6/E7 mRNA positivity was confirmed in 2 patients (4%) of the whole cohort. Both patients were free from recurrence with 3 years of follow-up. Due to small sample number, we did not noticed any correlation with survival.

Mean PD-L1 transcript level was 28.55 (median 2.26; SD 119.28). There was no correlation between the level of PD-L1 and age of patients, smoking status, alcohol dependence, T stage, N stage, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, extranodal extension, margin status, recurrence, and adjuvant treatment.

We used Cox proportional hazard regression analysis to assess whether PD-L1 expression impacts patients’ overall survival. We used a model with one variable: log10(ΔΔCq) of PD-L1.

After fitting the model, it was determined that PD-L1 expression was a key predictor variable influencing survival probability (HR = 0.5655, 95% CI = 0.3448–0.8851, p = 0.0118). Based on these results, higher expression of PD-L1 was indicative of significantly improved overall survival. Analysis of scaled Schoenfeld residuals vs. time graph, and deviance residuals vs. covariate graph, showed no gross violation of proportional hazards assumption and no apparent outliers to be removed.

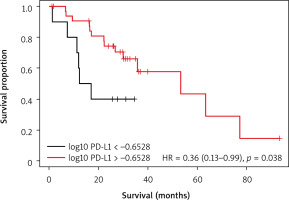

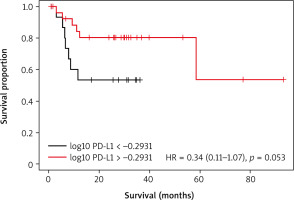

To assess the effect of PD-L1 mRNA level on patient outcomes the transcript level was divided into 2 groups: low and high mRNA level determined by optimal cutoff point based on OS and DFS. Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed a significantly better OS in patients with higher level of PD-L1 (p = 0.038) (Fig. 2). No significant difference was observed between low and high expression of PD-L1 regarding DFS (p = 0.053) (Fig. 3).

Figure 1

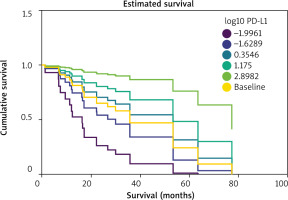

mRNA level of PD-L1 is a predictor of overall survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) patients. Estimated cu mulative survival graph was plotted for six log10 expression values: minimum (–1.9961), first quartile (–0.6289), second quartile (0.3546), third quartile (1.175), maximum (2.8982), and all patients (baseline)

Discussion

Our study is the first to summarise the true incidence of HPV and PD-L1 status in oral SCC.

There are several papers discussing the HPV status in oral cancer, but the method of extraction is nonspecific. In a recent review by Shigeishi [8], the author discusses the differences in HPV incidence. There has been wide variation, from 2.2% in the Netherlands, 9.8% in USA, to over 43% in India, where the author suggested that it could be influenced by constant inflammation due to betel nut chewing. But there have been differences in examining the HPV incidence. Most of the studies were based on HPV-DNA by PCR, and only few studies tested the HPV incidence by HPV E6/E7 mRNA. In terms of detection, the association between HPV and p16 expression (routinely tested in oropharyngeal cancer) in OSCC varies. p16 expression is occasionally inhibited by mutation and methylation of its gene in oral cancers, suggesting that p16 expression is not necessarily dependent on E7 in oral cancers. Therefore, p16 expression is not applicable as a surrogate marker of HPV in oral cancers, concluding that high-risk HPV DNA and E6/E7 mRNA expression should be investigated to determine the presence of active HPV in agreement with high-risk HPV infection in oral cancers. In a study from Spain [15] there were 17% patients who were HPV+, but the authors only tested p16 status. In terms of prognosis, the authors stated that positive HPV status decreases overall survival. In a review published by Katirachi et al. [16], the authors stated that the HPV status in oral cancer varies widely, from 0% to 37%, concluding that HPV status may not be a strong risk factor in oral cancer oncogenesis. The authors examined over 5000 pts, but the differentiation method of HPV testing included p16, HPV – DNA, and E6/E7 mRNA; therefore, even with such a high number of patients the summary is somewhat controversial. Additionally, the authors did not examine the impact of HPV on survival. Christianto et al. [17] in their review focused on the prognostic aspect of HPV in oral cancer. The authors analysed over 3000 pts and concluded that HPV+ oral cancer patients have shorter overall survival but with no impact of disease-free survival, and local or regional control. The greatest limitation of their study was the differences in detection in the 22 included studies. The most adequate review was published by de Carvalho Melo et al. [18], in which the authors included 5 studies (2 from the United States and one each from China, Greece, and Chile). The HPV activity was measured by E6 and E7 mRNA, and 4.4% of the oral cancer patients were HPV positive, which is consistent with our results. Only 13% of the study population were Europeans. The authors did not study the prognostic significance of HPV infection. Finally, in a single-centre study from Japan [19]the authors analysed 127 pts with mobile tongue cancer and tested for HPV using p16, HPV-DNA, and E6/E7 mRNA. There were 14% of p16+, 7.1% HPV-DNA+, and 5.5% E6/E7 mRNA+ patients. What is interesting, out of 7 E6/E7 mRNA+ patients, only 3 had p16 overexpression. In terms of survival, only patients with p16 overexpression had better cancer-specific survival in comparison to p16-negative pts. HPV DNA and E6/E7/mRNA status had no impact on survival. To summarise, most of the studies suggest that even though HPV is detected in oral cancer patients, but contrary to oropharyngeal cancer patients, the virus is not biologically active in oral cancer. What should also be emphasised is that HPV is transmitted sexually, and sexual behaviour varies in each part of the world, which in turn will translate into the wide variation in presented results.

When discussing the incidence of PD-L1 positivity in oral cancer, most of the studies use immunohistochemi-stry for staining and composite positive score to evaluate the PD-L1 status, which makes it difficult to compare to our results. In a study by Subramaniam et al. [20] the authors examined 64 pts with oral cancer and found that the expression of PD-L1 in the whole group was low and did not impact survival apart from higher risk of lymphovascular invasion and bone invasion. Authors from Japan [21] analysed patients with tongue squamous cell cancer and concluded that 11.6% of pts had more than 50% PD-L1 positive cells, and about 60% of these had poor survival with nodal metastasis. In a recent study by Soopanit et al. [22], the authors evaluated PD-L1 status in non-drinkers/non-smokers in comparison to a drinkers/smokers group. In a group of 64 pts PD-L1 positivity was more frequent in the non-smokers/non-drinkers group (75% vs. 45.8%, respectively). The authors did not analyze separately the impact of PD-L1 status on survival. Adeoye et al. [23] in their review also focused on non-drinker/non-smoker oral cancer patients and discovered that this group had elevated levels of PD-L1. In our study we did not notice any connection with drinking and smoking. Finally, Kujan et al. [24] in their review analysed potential biomarkers in oral cancer, focusing on PD-L1 status. The authors analysed over 30 studies for predictive and prognostic roles of PD-L1 in oral cancer, but the results were contradictory. There were studies in which higher PD-L1 status improved survival, but in some of those studies the patients were treated with immunotherapy, which makes it difficult to compare with our results. In most studies, higher PD-L1 status led to decreased survival. Again, methods of detection were different to our study. To summarise, it should be stressed that differences in the cited studies are mostly due to high heterogeneity in terms of PD-L1 method detection. Most studies used IHC with several clones. Another factor is the scoring system, where subjectivity may exist when manually assessing PD-L1 staining. Therefore, standardised guidelines and methods of examination are crucial to overcome those issues.

Strengths and limitations

The greatest strength of our study is the method of detection of HPV and PD-L1, which we believe is the strongest and most reliable and repetitive method of detection. Another strong factor is that the patient group is homogenous with decent follow-up. The limitation of our study is the low number of patients qualified for the study.

Conclusions

Our results clearly show that HPV status is irrelevant in oral cancer, it does not affect survival, and should not be taken as prognostic factor. On the other hand, patients with higher PD-L1 status in our study had better survival, which is contradictory to most of the published studies. The reason for this may be the different detection me-thods, where we believe that examination through mRNA to be more precise and repetitive. Studies with higher numbers of patients are needed to validate our conclusions.