Introduction

Cervical cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women, after breast cancer. Despite advances in radical treatment, the relapse rate remains significant, affecting 11–22% in the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stages Ib–IIa and 28–64% in FIGO stages IIb–IVa [1]. The burden of cervical cancer varies considerably across Europe, with Eastern European countries, including Poland, experiencing some of the highest incidence rates and less favourable treatment outcomes compared to Western Europe. Although the incidence of cervical cancer in Poland is declining, the country still reports one of the highest mortality rates in Europe (10.5 per 100,000), which is double the European average, alongside a low 5-year survival rate of 55.1%. Contributing factors include limited human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination (10%, with a national program initiated only in 2023) and inadequate uptake of cytology screening (< 25%), which continue to impede improvements in outcomes [2].

Treatment for metastatic cervical cancer typically involves systemic therapy, with a platinum-based chemotherapy regimen serving as the backbone. The addition of bevacizumab has shown significant improvements in overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in the GOG 204 phase III clinical trial [2] and has become a standard component of first-line therapy. For patients with programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1)-positive tumours, pembrolizumab (anti-programmed death receptor 1 – PD-1, monoclonal antibody) combined with chemotherapy and bevacizumab further improves outcomes, providing a substantial survival benefit [3]. For those with progression after chemoimmunotherapy, subsequent-line therapies include immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) (if not previously administered), tisotumab vedotin (not approved in Europe), or single-agent chemotherapy tailored to the patient’s prior treatment history and molecular profile. Despite these advances, the prognosis remains poor, with an objective response rate (ORR) of up to 20%, particularly for patients previously exposed to platinum-based therapies, highlighting the need for continued research into effective treatment options for this population [4–6].

Immune checkpoint inhibitors represent a promising therapeutic option for patients with metastatic cervical cancer in subsequent lines of treatment, particularly those with PD-L1-positive tumours. Pembrolizumab, approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration [7], has demonstrated response rates of 15–17% in the second-line setting when not previously administered, as evidenced in the phase II trial [8]. Cemiplimab (anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody) has also shown efficacy in recurrent cervical cancer without prior exposure to immunotherapy in a phase III trial, achieving a 30% reduction in the risk of death (median OS: 12.0 months vs. 8.5 months; hazard ratio [HR] for death, 0.69; 95% CI: 0.56–0.84) and a 25% reduction in the risk of disease progression (HR 0.75; 95% CI: 0.63–0.89) compared with chemotherapy [9]. The objective response rate increased from 6.3% with chemotherapy to 16.4% with cemiplimab. Programmed death ligand 1 expression was retrospectively assessed in baseline tumour samples from one-third of patients. Among patients with PD-L1 expression ≥ 1%, cemiplimab further improved OS (13.9 vs. 9.3 months; HR 0.70; 95% CI: 0.46–1.05), while its benefit was less pronounced in those with PD-L1 expression < 1% (7.7 vs. 6.7 months; HR 0.98; 95% CI: 0.59–1.62). The European Medical Agency approved cemiplimab for this indication regardless of PD-L1 expression [10].

In Poland, pembrolizumab, combined with chemotherapy, has been reimbursed since July 2024, and cemiplimab as monotherapy in subsequent lines of treatment since January 2025. Before this, ICIs were accessible only through clinical trials or the rescue access program in reference centres, contingent on regional authority approval and the unavailability of better treatment options. This study aims to present real-world data from the rescue access program on ICI monotherapy in patients with recurrent/metastatic cervical cancer (r/mCC), and to compare our findings with pivotal clinical trials and other real-world evidence (RWE).

Material and methods

Study design and population

This RWE study was conducted across 5 reference centres in Poland, because the rescue access program is only available in such institutions. It involved 39 adult patients with r/mCC. The study cohort comprised individuals who had progressed on prior platinum-based chemotherapy and were subsequently treated with ICI monotherapy under a rescue access program. Eligibility required completion of at least one treatment cycle between 18 October 2022 and 30 January 2025. Data collection concluded on 30 January 2025, and it was conducted retrospectively for baseline characteristics and prospectively for outcomes.

The study adhered to the Good Reporting of Outcomes in Real-world Evidence Studies (GROW) guidelines, emphasising robust RWE methodology [11]. Key aspects such as study design, patient demographics, data collection, strategies for handling missing data, and safety evaluations were systematically addressed. Supplementary Table S1 outlines detailed examples of the application of the GROW principles in this study.

Eligibility criteria

The patients were treated under a rescue access program, with eligibility criteria aligned with pivotal clinical trials and a summary of product characteristics [7, 10]. The local pathological review confirmed all cancer diagnoses, and the study included patients with squamous-cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and adenosquamous carcinoma, regardless of PD-L1 expression status. Prior exposure to anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 therapies was not allowed. Patients with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance-status score of 0–2 were enrolled. Participants were required to have adequate renal, liver, and bone marrow function, as well as measurable disease.

To enhance the population’s representativeness, the study included patients reflective of real-world clinical practice, encompassing a range of histologic subtypes and ECOG performance statuses (0–2). This approach aimed to capture the diversity of clinical scenarios observed in routine oncology settings.

Exclusion criteria included previous treatment with ICIs in clinical trials, ongoing or recent autoimmune disease, immunosuppressive glucocorticoid use exceeding 10 mg of prednisone daily (or equivalent) within 4 weeks prior to the initial dose, and active infections requiring treatment (bacterial, viral, fungal, or mycobacterial).

Data collection and quality assurance

Data were retrospectively obtained from electronic health records, encompassing baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, prior treatment history, PD-L1 expression, and HPV status when evaluated. Information on therapeutic outcomes and adverse events (AEs) was prospectively documented.

Programmed death ligand 1 expression was presented as a combined positive score (CPS), defined as the ratio of PD-L1-positive cells (tumour cells, lymphocytes, and macrophages) to the total number of viable tumour cells multiplied by 100. Programmed death ligand 1 positivity was defined as a CPS > 1. The study was conducted on paraffin-embedded tissue sections using immunohistochemistry with the monoclonal mouse anti-human PD-L1 antibody (DAKO) and the EnVision Flex High pH Detection Kit (DAKO).

To maintain data integrity, the research team conducted thorough assessments of the completeness and accuracy of the extracted information. Missing data were addressed through complete case analysis, with no imputation methods applied.

Follow-up

The patients were followed up during subsequent drug administrations every 3 weeks or earlier if the emergence of toxicity required clinical supervision. Additional assessments were conducted every 12 weeks or sooner if clinically indicated, with imaging (computed tomography – CT, scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis) performed according to response evaluation criteria in solid tumours (RECIST) v1.1 guidelines [12]. Survival status was recorded for patients during subsequent lines of treatment and for those disqualified from further therapy to provide additional data on OS.

Study objectives and outcome measures

The primary objective of the study was to assess the RWE of ICI monotherapy in patients with r/mCC treated in later lines of therapy. Efficacy endpoints included OS, defined as the duration from the start of treatment to death; PFS, measured as the time from treatment initiation to either radiologically confirmed disease progression (PD) or death; ORR, representing the proportion of patients achieving a complete response (CR) or partial response (PR); and disease control rate (DCR), calculated as the proportion of patients attaining CR, PR, or stable disease. Tumour response was evaluated locally in each centre using RECIST v1.1 criteria [12], with CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis performed every 12 weeks or earlier if clinically warranted.

The secondary objective was to evaluate the safety profile of the treatment, focusing on the incidence, type, and severity of AEs.

Safety assessments

Adverse events were classified according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v5.0 [13]. Immune-related adverse events (irAEs) were defined as treatment-emergent toxicities with a presumed immune-mediated mechanism based on a clinical assessment or requiring immunosuppressive therapy, as per European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines [14]. The safety evaluation concentrated on the frequency, nature, and severity of AEs. The management of irAEs followed the recommendations outlined in the ESMO guidelines [14].

Interventions

The patients were treated with either cemiplimab or pembrolizumab, as determined by the discretion of the treating physician. The doses followed the prescribing guidelines approved by the European Union [10, 13]. Cemiplimab was administered at 350 mg, and pembrolizumab at 200 mg, both given intravenously every 3 weeks. Treatment continued until PD, the occurrence of unacceptable toxicity, or the withdrawal of patient consent.

Although dose modifications were not allowed per protocol, treatment delays were permitted based on clinical assessment. However, these delays were not included in the analysis.

Bias and confounding

This study is subject to inherent risks of bias due to the retrospective nature of certain data collection processes. Selection bias stemmed from the treating physicians’ discretion in determining patient eligibility for the rescue access program, with regional authorities validating the applications. Information bias was minimised by meticulous manual data verification and direct clarification with treating physicians. Pathological assessments of the CPS and HPV status were conducted locally without centralised validation.

To address variability across centres, the study adhered to the ESMO guidelines [15] and employed standardised RECIST v1.1 criteria for tumour response evaluation [14].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using PS Imago Pro 9. Depending on the data distribution, categorical variables were compared between the groups using Fisher’s exact test or chi-square test. Continuous variables, determined to have non-normal distributions based on the Shapiro-Wilk test, were analysed using the Mann- Whitney U test. Overall survival and PFS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Survival differences were assessed through log-rank tests and Cox proportional hazards models. Variables with p-values < 0.05 in univariate comparisons were considered potential confounders and included in multivariate analyses. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 summarises the baseline characteristics of the study population at the time of radical treatment and immunotherapy initiation. Most patients (72%) had squamous cell carcinoma with unknown HPV status and prior radiochemotherapy. Half received bevacizumab in the first-line treatment of recurrent/metastatic disease and initiated ICIs after progression on platinum-based chemotherapy, while the remaining were heavily pretreated with ≥ 2 prior systemic therapies. At ICI initiation, 60% had PS 1, whereas 25% had PS 2. Combined positive score status was available in one-third of cases. The most common metastatic sites were non-regional lymph nodes, lungs, and bones.

Table 1

Baseline clinical characteristics of the enrolled patients (n = 39)

Treatment outcomes

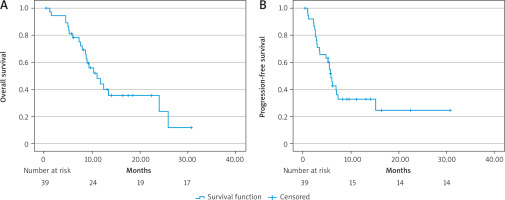

Immunotherapy was initiated at a median of 26.6 months (interquartile range – IQR: 26.5–65) from the primary diagnosis. Most of the patients received cemiplimab (n = 37, 94.9%), whereas 5.1% (n = 2) received pembrolizumab. The patients received a median of 6 cycles of ICIs (IQR: 4–9) during the treatment period of 4.9 months (IQR: 2.1–8.1). After a median follow-up of 8.8 months (IQR: 5.8–13), the median PFS was 5.7 months (95% CI: 4.9–6.4) (Fig. 1 A), and the median OS was 10.9 months (95% CI: 7.3–14.5) (Fig. 1 B). The 6-month and 12-month survival rates were 79.5% and 53.8%, respectively. As the best response to treatment, the DCR was 64% (n = 25), with an ORR of 23% (n = 9). Unfortunately, 35% of patients (n = 14) experienced PD at the first efficacy assessment.

During treatment, 3 patients (7.7%) received additional palliative radiotherapy, and one patient underwent metastasectomy (2.6%).

At the data cut-off, 33.3% of the patients (n = 13) were still receiving ICIs treatment, while 66.7% (n = 26) had discontinued therapy. Treatment discontinuation was due to PD or death in 61.5% of the patients (n = 24), while toxicity was the direct cause in only 5.1% (n = 2).

Safety

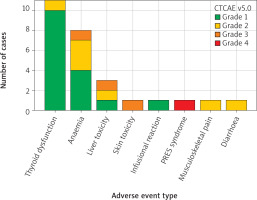

A total of 27 AEs were recorded in 23 patients (59%). Among them, 18 patients (78.3%) experienced a single episode, 3 patients (13%) had 2 episodes, and one patient (4.3%) had 3 episodes. Most AEs were grade 1 (59.3%, n = 16), followed by grade 2 (26%, n = 7), grade 3 (11.1%, n = 3), and grade 4 (3.7%, n = 1). The number and severity of all AEs are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Severity and frequency of reported adverse events according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (ver. 5.0)

PRES – posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome

Among irAEs, endocrine toxicities, primarily thyroid dysfunction, were the most frequent (40.7%, n = 11), followed by hepatic toxicity (11.1%, n = 3), skin toxicity (3.7%, n = 1), infusion reaction (3.7%, n = 1), and rheumatic toxicity (musculoskeletal pain, 3.7%, n = 1). Non-immune-related AEs included anaemia (29.6%, n = 8) and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome related to uncontrolled hypertension (3.7%, n = 1).

Adverse events typically occurred early in treatment, with a median onset of 2.5 months (IQR: 1–4 months). Systemic steroids were required in 3 patients (7.7%), with doses of 1 mg/kg prednisone (n = 2) and 0.5 mg/kg prednisone (n = 1). In 2 cases (5.1%), toxicity led to treatment discontinuation.

Factors influencing the outcome

In the univariate analysis (Table 2), liver metastases were associated with shorter PFS (HR 3.2, 95% CI: 1.2–8.2, p = 0.02), but this was not confirmed in the multivariate analysis. Prior bevacizumab use also correlated with worse PFS (HR 2.4, 95% CI: 1.1–5.5, p = 0.04) but lost significance after adjustment. Conversely, irAE occurrence was linked to significantly prolonged PFS (HR 0.2, 95% CI: 0.1–0.6, p = 0.002), particularly endocrine irAEs (HR 0.2, 95% CI: 0.06–0.6, p = 0.004).

Table 2

Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors potentially influencing treatment outcome

Bone metastases were associated with reduced OS in the univariate analysis (HR 2.9, 95% CI: 1.2–7.2, p = 0.02), but this effect was not retained in the multivariate ana- lysis. The use of bevacizumab showed a similar pattern (HR 2.7, 95% CI: 1.1–6.8, p = 0.04). Unlike in PFS, irAEs did not significantly impact OS.

Impact of prior bevacizumab

Because the univariate analysis demonstrated that patients receiving bevacizumab in the first-line setting had significantly worse outcomes in terms of PFS and OS compared to those who did not, we conducted an additional analysis comparing these 2 subgroups to further investigate potential differences in baseline characteristics and treatment outcomes. Bone metastases, related to worse OS in the univariate analysis, were significantly more frequent in the bevacizumab group (9 [45%] vs. 1 [5.3%] patient/s, p = 0.01). Additionally, patients receiving bevacizumab had a higher number of organs with metastatic lesions compared to those who did not (1.95 vs. 1.17, p = 0.02). Furthermore, the number of immunotherapy cycles was significantly lower in the bevacizumab group (5.65 vs. 12.5, p = 0.02), suggesting a shorter duration of immunotherapy in these patients.

Discussion

This study evaluated the RWE of ICI monotherapy in r/mCC treated in later lines of therapy. Disease control was achieved in two-thirds of the patients, while one-third had progressive disease at the first efficacy assessment. Regarding safety, AEs were primarily mild and most commonly involved thyroid dysfunction. Severe toxicities were infrequent, and treatment discontinuation due to AEs occurred in only 2 patients. Immunosuppressive therapy was required in 3 patients, all of whom responded to systemic steroids, which were sufficient for symptom management. In exploratory analyses, irAEs, particularly endocrine toxicities, were associated with prolonged PFS, but no significant correlation was found with OS. Conversely, liver and bone metastases and prior bevacizumab were correlated with worse outcomes in univariate analysis, although these associations did not persist in multivariate analysis. However, the lack of statistical significance in multivariate analyses suggests that these associations should be interpreted with caution. Additionally, subgroup comparisons indicated that patients treated with bevacizumab had a higher metastatic burden and received fewer cycles of immunotherapy, suggesting that bevacizumab was administered more frequently to patients with more advanced disease, which may have influenced treatment exposure and overall outcomes.

Table 3 provides an overview of the efficacy and safety outcomes of ICI monotherapy in subsequent lines of treatment for cervical cancer in other studies. The objective response rates for pembrolizumab or cemiplimab ranged from 9.4 to 24% [16, 17], with CR rates of 3–9% [16, 17] and PR rates in up to 20% of patients [16], similar to our findings with an ORR of 23%. Durable responses were observed, particularly in patients with favourable performance status (≤ 1) or PD-L1-positive tumours (CPS ≥ 1%) [15, 18]. The median PFS varied from 2.8 to 4.0 months [16, 17, 19], while the median OS was 8.4–12.0 months [16, 20], which aligns with our findings.

Table 3

Summary of studies on immune checkpoint inhibitors as monotherapy in advanced cervical cancer

| Ref. | Study design | Population | Treatment | Outcomes | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oaknin et al. [20] | Phase 3 randomised trial EMPOWER-Cervical 1; final OS analysis with 47.3-month median follow-up | 608 patients with recurrent cervical cancer after progression on first-line platinum-based chemotherapy; PD-L1 status not required; included both PD-L1-positive and negative populations | Cemiplimab vs. physician’s choice of single-agent chemotherapy | Follow-up 47.3 months; median OS: 11.7 months (cemiplimab) vs. 8.5 months (chemotherapy) (HR 0.67, 95% CI: 0.56–0.80, p < 0.00001). Survival benefit observed in both PD-L1-positive and negative populations | AEs of any grade: 89.7% vs. 91.7%; treatment-related AEs: 57.3% vs. 81.7%; most common: nausea (9.3% vs. 30.3%), fatigue (10.7% vs. 13.4%), anaemia (7.7% vs. 36.9%). Treatment discontinuation due to AEs: 9.0% vs. 5.2% |

| Hasegawa et al. [16] | Phase 3 subgroup analysis of EMPOWER-Cervical 1, conducted in Japan | 56 patients; PD-L1 status not required | Cemiplimab vs. investigator’s choice of single-agent chemotherapy | Follow-up 13.6 months; median OS: 8.4 months (cemiplimab) vs. 9.4 months (chemotherapy) (HR: 0.86); median PFS: 4.0 vs. 3.7 months; ORR: 17.2 vs. 7.4% | Grade ≥ 3 AEs: 37.9% (cemiplimab) vs. 66.7% (chemotherapy); overall AEs: 79.3% vs. 100% |

| Chung et al. [8] | Phase 2 basket trial (KEYNOTE-158), conducted internationally | 98 patients; median age: 46 years (range, 24–75); 83.7% with PD-L1-positive tumours (CPS ≥ 1); 65.3% with ECOG 1; 77 previously treated with ≥ 1 lines of chemotherapy for recurrent/metastatic disease | Pembrolizumab | Follow-up 10.2 months; ORR: 12.2% (95% CI: 6.5–20.4%); all responses in PD-L1-positive tumours: ORR 14.6% (95% CI: 7.8–24.2%); median DOR not reached | AEs in 65.3% of patients, most commonly hypothyroidism (10.2%), decreased appetite (9.2%), and fatigue (9.2%); grade ≥ 3 events: 12.2% |

| Choi et al. [15] | Multi-centre retrospective study conducted at 16 institutions in Korea (2016–2020) | 117 patients; median age: 53 years (range, 28–79); 54.7% with ECOG ≥ 2; median prior chemotherapy lines: 2 (range, 1–6) | Pembrolizumab | Follow-up 4.9 months; ORR: 9.4% (3 CR, 8 PR); median time to response: 2.8 months; median DOR not reached; in ECOG ≤ 1 population (n = 53): ORR 18.9%, median DOR: 8.9 months | AEs in 47% of patients, including grade ≥ 3 events in 6.8%; two treatment-related deaths reported |

| Alholm et al. [17] | Observational study treated in US community oncology settings (2014–2019) | 130; mean age: 53 years; > 60% with ECOG 0–1; second-line therapies | Chemotherapy (46%), combination therapy (35%), pembrolizumab (15%), and bevacizumab (5%) | Median OS: 9.1 months (95% CI: 7.2–12.2); median TTD: 2.8 months (95% CI: 2.5–3.3); median TFST: 4.9 months (95% CI: 4.2–5.7); no significant differences across second-line treatments | Safety data not reported |

| Miller et al. [18] | Retrospective cohort study conducted at a single institution in the US (August 2017 – November 2019) | 14 patients; PD-L1 CPS ≥ 1% | Pembrolizumab | Follow-up 14.4 months; ORR: 21% (2 PR, 1 CR); durable clinical benefit rate: 36% (2 SD ≥ 6 months); median TMB in responders: 12.7 mutations/megabase vs. 3.5 in non-responders | Safety data not reported |

| Tuninetti et al. [19] | Real-world retrospective multicenter study conducted in Italy (2022–2023) | 135 patients after platinum-based chemotherapy | Cemiplimab | Median OS: 12.0 months (12.0–NR); median PFS: 4.0 months (range: 3.0–6.0); CR/NED: 8.6%; PR: 21.1%; SD: 14.8%; PD: 44.5% | Most common AEs: anaemia (39.1%) and fatigue (27.8%); immune-related AEs occurred in 18.0% |

| Qi et al. [21] | Systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 clinical trials | 523 patients | Immune checkpoint inhibitors (PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors) | Pooled ORR: 24% (95% CI: 11–39%); CR: 3% (95% CI: 2–5%); PR: 20% (95% CI: 8–36%); SD: 31% (95% CI: 23–40%) | AEs rate (any grade): 81% (95% CI: 72–88%) |

| Chen et al. [30] | Individual patient data-based meta-analysis of 8 studies (randomized clinical trials and single-arm studies) | 1110 patients, stratified by low PD-L1 expression (CPS < 1) | ICI monotherapy vs. ICI combination therapy vs. non-ICI treatment | ICI monotherapy no OS benefit (HR = 2.60, 95% CI: 1.31-5.16, p = 0.008) and worse PFS (HR = 7.59, 95% CI: 3.53-16.31, p < 0.001) vs. non-ICI treatment or ICI combination therapy. Combination therapy OS benefits over non-ICI treatment (HR = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.36-1.04, p = 0.06) | Safety data not reported |

| Djuraev et al. [23] | Abstract, Phase 3 randomized trial comparing cemiplimab with single-agent chemotherapy | 180 women after progression on first-line platinum-based chemotherapy; CPS status not required | Cemiplimab vs. physician’s choice of single-agent chemotherapy | Median OS: 12.4 months vs. 7.5 months (HR 0.69; p < 0.001); PFS: HR 0.75 (p < 0.001); ORR: 16.1% vs. 6.3% | Grade ≥ 3 AEs: 45% (cemiplimab) vs. 53.4% (chemotherapy); consistent survival benefit across histologic subtypes and CPS levels |

| Ahmed et al. [29] | Abstract, Systematic review of 7 studies | 411 patients; mean age: 48 years (range, 21–76); received a median of 1–7 prior therapies | Pembrolizumab | Follow-up 10.5 months; ORR: 15%; CR: 3.8%; PR: 9.7%; stable disease: 19.3%; progressive disease: 41%; 6-month OS (3 studies): 67% | Safety data not reported |

[i] AEs – adverse events, CI – confidence interval, CPS – combined positive score, CR – complete response, CTLA-4 – cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4, DOR – duration of response, ECOG – Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, HR – hazard ratio, ICI – immune-checkpoint inhibitors, NR – not reached, NED – no evidence of disease, ORR – objective response rate, OS – overall survival, PD-1 – programmed cell death protein 1, PD-L1 – programmed death-ligand 1, PFS – progression-free survival, PR – partial response, SD – stable disease, TFST – time to first subsequent treatment, TMB – tumour mutational burden, TTD – time to treatment discontinuation

Regarding safety, ICIs were generally well-tolerated, with AEs of any grade occurring in 47–81% of patients [15, 21, 22]. Grade ≥ 3 AEs, including irAEs, were reported in 6.8–45% of cases [15, 23], with the most common toxicities being fatigue, hypothyroidism, and anaemia. Compared to chemotherapy, ICIs showed a lower incidence of severe AEs, enhancing their safety profile [17, 20]. In our study, we observed a similar trend with AEs in 59% of patients. Furthermore, the occurrence of AEs, particularly thyroid dysfunction, demonstrated predictive significance for treatment outcomes, consistent with findings that we previously reported in cervical cancer and other malignancies [24–28].

However, the included studies varied significantly in design, ranging from clinical trials [8, 16, 20] and systematic reviews [21] to retrospective cohort studies [15, 18, 19], and some data originated from conference posters without access to full publications [23, 29]. This heterogeneity in the study design introduces variability in the level of evidence, with clinical trials generally providing more robust data but often under controlled conditions that may not fully reflect real-world practice. Conversely, retrospective studies and RWE often capture more diverse patient populations and clinical scenarios but are prone to biases such as incomplete data and selection bias. Furthermore, the populations studied are diverse, with many investigations focusing on Asian [15, 16] or U.S.-based cohorts [18, 17], which may not fully reflect the characteristics of Polish or broader Caucasian populations. Differences in healthcare systems, genetic backgrounds, and treatment access could influence outcomes, underscoring the need for cautious interpretation of results and additional studies in European settings. Most studies had relatively short follow-up durations (4–14 months) [15, 18], which restricts the ability to assess long-term survival outcomes, durability of responses, and late-onset AEs.

Our study provides valuable RWE on the use of ICIs in r/mCC, addressing significant gaps in the current literature. Given that cervical cancer is rare in most developed countries and immunotherapy remains unavailable in many regions, data on ICI efficacy and safety in this setting are limited. Additionally, a notable lack of studies from Poland and the broader Eastern European population makes this analysis particularly relevant for understanding treatment outcomes in this region. Moreover, the study includes a heterogeneous and heavily pretreated population, providing insights into ICI use beyond strictly selected clinical trial cohorts.

Despite these strengths, several limitations should be acknowledged. The main limitation of the study is the relatively small population. However, we present data on treatment not reimbursed in Poland at the time of data cut-off. The study is subject to selection bias because, at the time of analysis, ICI treatment was only available through a rescue access program in reference centres and required central validation by regional consultants, limiting access to a subset of patients who progressed after platinum-based chemotherapy. Consequently, the findings may not fully represent all patients with metastatic cervical cancer in Poland. Additionally, response assessments based on CT scans and biomarker evaluations (PD-L1, CPS) were conducted locally, introducing potential variability in interpretation. The lack of centralised radiologic review and biomarker validation may have influenced response classification and treatment stratification. Furthermore, this study did not include a direct comparison between ICIs and standard chemotherapy used in later lines of treatment, which limits conclusions regarding the relative efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness of these therapies. Another limitation is that the study did not directly compare different ICIs, as both cemiplimab and pembrolizumab were included. However, the pembrolizumab subgroup was very small, increasing the heterogeneity of the study population. Regarding safety assessments, data collection was retrospective and based on medical records, which may have led to underreporting of AEs compared to clinical trials, where toxicity monitoring is more structured and systematic. Finally, while the follow-up period was relatively short, it is important to note that only one-third of the patients included in the analysis were still receiving treatment at the time of the data cut-off.

Conclusions

Immune checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy demonstrated modest clinical activity in pretreated patients with r/mCC, achieving disease control in two-thirds of the patients, while one-third experienced primary progression. Treatment was generally well tolerated, with thyroid dysfunction being the most common AE and a potential predictor of treatment response. These findings provide important RWE from an Eastern European population, where access to immunotherapy has been limited. Given the recent implementation of a fully reimbursed program in Poland, our data offer a solid foundation to support its utilisation in clinical practice in a broad population.