Introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is the seventh leading cause of death in Europe for cancer-related reasons [1, 2]. In accordance with the National Cancer Registry in 2020 in Poland a total of 3 589 people (1764 men and 1825 women) developed PC. The highest incidence was observed in the Lower Silesian Voivodeship and the lowest in the Lesser Poland Voivodeship [3].

Complete surgical resection provides the only chance for a cure; however, only 20% of patients are diagnosed with resectable disease [4, 5]. Specific early symptoms are generally lacking, which contributes to delayed diagnosis [6, 7]. In these cases, PC is diagnosed in a metastatic stage with a particularly poor prognosis [8] and a total survival rate of 6% at 5 years [4, 5]. An additional option for the induction treatment of locally advanced PC is a combination of chemotherapy with stereotactic body radiotherapy [9]. For PC patients who were not eligible for surgical resection, chemotherapy and radiotherapy may be considered as treatment options [10–12]. The most common type of PC, comprising approximately 80% of new cases is pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [13]. It is characterized by resistance to chemotherapy and radiation. New therapeutic options that demonstrate statistically significant improvements in overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) are still being sought.

Since 1997, gemcitabine monotherapy (GEM) has been the standard therapy treatment for patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer (mPC) [14]. A combination of gemcitabine with nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel was found to produce further improvements in survival [15]. In the phase III metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma clinical trial (MPACT) published in 2013, a combination treatment of nab-paclitaxel with gemcitabine (GEM-NAB) achieved better OS compared to GEM; median OS 8.5 vs. 6.7 months. However, the median PFS was 5.5 months vs. 3.7 months [16, 17]. In the MPACT trial, GEM-NAB was well tolerated, grade > 3 adverse events (AEs) were effectively managed by dose reductions and delays [18]. These encouraging results have set a new standard and international guidelines now recommend GEM-NAB as first-line treatments in patients with mPC [19, 20].

A combination regimen consisting of 5 FU/leucovorin plus oxaliplatin and irinotecan (FOLFIRINOX) has also been shown to improve survival compared with GEM [21, 22]. The American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends FOLFIRINOX for younger patients with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG) of 0–1 [23, 24]. Gemcitabine monotherapy is recommended for patients with ECOG 2 with worse comorbidity profiles.

There are only limited data on real-world treatment outcomes in PC, and data from clinical trials, which conform to strict eligibility criteria, are not representative of real world practice. The aim of our retrospective analysis of patients with mPC was to assess the effectiveness and treatment tolerance GEM-NAB in the real world. We also report the development of a validated predictive model for survival based on routinely collected data (demographic, clinical and laboratory parameters).

Material and methods

Patient collection

The aim of the clinical study was a retrospective analysis of the medical history of 182 patients with the diagnosis of mPC, who were treated with GEM-NAB as part of the drug program initiated by the Minister of Health titled Treatment of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma between February 2017–September 2023 in the Oncology Department of the National Medical Institute of the Ministry of the Interior and Administration in Warszawa.

The drug program is a separate funding stream for financing drug technologies by the public payer, the National Health Fund. The decision to initiate the program is made by the Minister of Health following the receipt of opinions from the President of the Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Tariff System and the Economic Commission of the Minister of Health. The program precisely defines criteria for patient inclusion, monitoring, and exclusion from therapy, adhering to the fundamental requirements of a clinical trial program (through the criteria in the drug program are less restrictive than those adopted in clinical trials) [25].

Inclusion criteria were: cytologically or histologically confirmed metastatic adenocarcinoma PC, age ≥ 18 years, measurable tumour lesions, performance status of at least 70 according to the Karnofsky performance scale, normal values of renal and hepatic parameters, not eligible for chemotherapy according to the FOLFIRINOX regimen. In laboratory tests at qualification, bilirubin levels did not exceed 1.5 times the upper limit of normal, creatinine values remained normal, and haemoglobin ≥ 10 g/dl. The main exclusion criteria were a neutrophil count less than 1,500/mm3 and a platelet count less than 100,000/mm3 [26]. The cancer stage was determined based on computed tomogra- phy (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with imaging examinations no later than 4 weeks before the commencement of treatment. During each 28-day cycle, nab-paclitaxel was administered intravenously over 30–40 minutes at a dose of 125 mg/m2 on the 1st, 8th and 15th days, followed by gemcitabine at a dose of 1,000 mg/m2 administered intravenously over 30–40 minutes. Prior to each subsequent administration, patients’ creatinine, bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and peripheral blood count were checked, and neurological assessments were conducted.

Treatment was performed until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity or patient refusal.

Data collection

The analysed medical data encompassed gender, age, ECOG, pathological variables (tumour site, tumour size, tumour stage), sites of metastases, treatment data (type of the operation, adjuvant chemotherapy), laboratory results, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), calculated as the absolute neutrophil count divided by the absolute lymphocyte count measured in ×103/ml, Ca 19.9 response rate, comorbidities, medications, biliary stent implantation and AEs.

Clinical data were extracted from medical records, and mortality data were obtained from the Polish national database. Laboratory tests were carried out by the Diagnostic Department of the National Medical Insti-tute of the Ministry of the Interior and Administration. Counts of inflammatory cells for calculating immune inflammation biomarker, NLR, were taken from results of laboratory tests, which were done immediately prior to treatment initiation. The response rate in terms of reduction in Ca 19.9 was evaluated before the beginning of treatment and then every 8 weeks until disease progression.

Treatment characteristics included concomitant treatments, treatments duration, discontinuation, number of cycles, dose reductions and interruptions. Dose modifications were based on the Summary of Product Characteristics [27].

Statistical analyses

The primary objective was OS defined as the time from the start of treatment to death from any cause. Secondary objectives included overall response rate (ORR), PFS defined as the time from the start of treatment to disease progression or all-cause death and safety. The analysis was conducted using PQStat version 1.8.6 and SPSS Statistics. Median OS (mOS) and median PFS (mPFS) were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method with 95% confidence intervals. The quantitative variables, NLR and CA 19.9, were transformed into binary variables with the cut-offs values of 3 and 34 U/ml, respectively.

Response criteria were assessed according to the radiological criteria, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1. Radiological assessments using CT of the chest, abdominal cavity, and pelvis were conducted every two treatment cycles.

Safety was assessed in terms of AEs graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0 [28].

Results

The analysis encompassed a cohort of 182 patients, comprising 104 women (57%) and 78 men (43%) undergoing treatment for mPC with first-line chemotherapy using GEM-NAB from February 2017 to September 2023. The age range of the research sample was 37–84 years, with a median age of 66 years (mean 64.8, standard deviation SD = 8.8). In the female subgroup, the median age was 67 years (mean 65.7, standard deviation SD = 8.6), while in the male subgroup, it was respectively 63.3 years (mean 63, standard deviation SD = 8.9). Most patients (94%) recorded a baseline ECOG of 1.

Regarding the location of PC, 64% (116) of cases were located in the head, 25% (46) in the body, and 11% (20) in the tail.

In the complete analysed cohort, 55 (30%) patients underwent Whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy, and 24 (13%) underwent distal pancreatectomy. Fifty one (28%) patients received adjuvant chemotherapy. The interval between the completion of adjuvant chemotherapy and the initiation of the GEM-NAB regimen was on average 250 days. Metastases were identified for 119 (65%) patients in the liver, for 43 (24%) in the lungs, for 38 (21%) in the lymph nodes, and for 23 (13%) in the peritoneum. Lung-only metastases were observed in 9% of patients. Patients received a total of 2–53 cycles of chemotherapy. Demographic, clinical and pathological features are reported in Table 1.

Table 1

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics (n = 182)

Complete response, as the best overall response, was observed for single patient. Partial response was observed for 25 out of 182 patients who had imaging performed by the end of data collection. Disease progression (PD) was observed for 35 patients. Disease stabilization was achieved for 97 patients. The remaining 24 patients continued treatment. A total of 182 patients had a baseline CA19.9 measurement. Fourteen percent of patients had a decrease from baseline of less than 50%, 23% had a decrease of at least 50%.

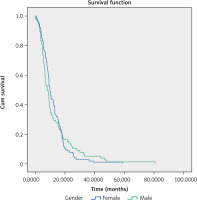

The mOS in the observed group was 9.2 months (95% CI: 8.3–10.03) (Fig. 1).

The analysis did not reveal statistically significant differences in mOS based on gender: for women, mOS was 9.9 months (95% CI: 8.8–11), and for men, mOS was 8.03 months (95% CI: 5.98–10.09), as well as for patients under 65 years, mOS was 9.17 months (95% CI: 7.34–11), and for patients of 65 years of age or more, mOS was 9.17 (95% CI: 8.27–10.07).

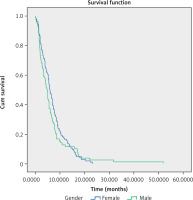

The median progression-free survival in the observed group was 5.47 months (95% CI: 4.83–6.1) (Fig. 2).

The analysis did not reveal statistically significant differences in mPFS based on gender: for women, the mPFS was 5.87 months (95% CI: 4.95–6.78); for men, mPFS was 4.7 months (95% CI: 3.69–5.71), and indicated age for patients under 65 years, mPFS was 5.47 months (95% CI: 4.88–6.04 ); for patients of 65 years of age or more, mPFS was 5.5 months (95% CI: 4.2–6.8).

The most common reasons for discontinuing treatment were PD (n = 35, 19%) and patient death (n = 33, 18%). After completion of treatment, 74 (41%) patients received 2nd line of chemotherapy, and further 23 (13%) patients received 3rd line of chemotherapy.

Safety

Treatment was well tolerated. Adverse events associated with treatment are presented in Table 2. The most frequent of them included alopecia, fatigue, neutropenia, anemia, and peripheral neuropathy. The most common grade > 3 AEs were neutropenia, fatigue, and anaemia (Table 3). Peripheral neuropathy occurred for only 4% of patients (no grade 4 reported).

Table 2

Treatment-associated toxicity (n = 182)

Table 3

Adverse events graded according to common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0 (n = 182)

Sixty one percent of patients had nab-paclitaxel dose reduction, and 51% of patients had gemcitabine dose reduction, most due to AEs. Dose delays ≥ 7 days occurred in 51% of patients. Detailed information about the effectiveness of treatment and use of additional therapies is available in Table 4.

Table 4

Effectiveness of treatment and additional therapies (n = 182)

Predictive factors

Analysis of the influence of baseline characteristics on survival showed that peripheral neuropathy and NLR < 3 influenced OS and PFS (Table 5).

Table 5

Multivariate analysis for overall survival and progression free survival

The antigen CA 19.9 < 34 before treatment and Ca 19.9 reduction ≥ 50% during treatment significantly influenced OS but did not reach the significance threshold in the PFS analysis. Mechanical jaundice had a significant impact on the PFS, but did not reach the significance threshold within the OS analysis. The time of initiation of treatment has significantly influenced OS, which includes introducing the need for immediate initiation of treatment. Also, the 2nd and 3rd lines of treatment showed a significant impact on OS, but it cannot be demonstrated which type of the 2nd and 3rd lines of treatment is significant.

Neither age, gender, ECOG, adjuvant chemotherapy, smoking or alcohol consumption showed a significant influence on median PFS and OS. Also the relationship between OS and PFS and the occurrence of other cancers for the patient has not been confirmed.

In the next step, the above estimates were used to determine the model’s predictive capabilities of OS and PFS (Tables 6, 7). The table of correlation coefficients indicates that both of these categories can be modelled with a different set of factors. The final forms of the obtained model estimates are presented below, sequentially eliminating statistically insignificant variables at the adopted significance level of p = 0.05.

Table 6

Predictive model for overall survival

Table 7

Predictive model for progression-free survival

The obtained models make it possible to indicate which parameters extend or shorten the patient’s life expectancy.

Discussion

Metastatic pancreatic cancer is a highly malignant tumour that poses significant challenges to treat. However, in recent years, progress has been observed in the treatment of advanced stages of the disease with the introduction of multidrug regimens [29].

This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness and safety profile of GEM-NAB for Polish patients with mPC, as the first line of treatment. Our findings are consistent with the analysis of the survival data of the MPACT study. Our analysis shows that treatment was well tolerated with a good ORR and a reduction in Ca 19.9 levels. Across the entire analysed patient group, we observed an extension of mOS by 0.7 months compared to the MPACT study (9.2 vs. 8.5 months), with the same mPFS (5.47 vs. 5.5 months). No statistically significant differences were found based on age and gender, supporting the inclusion of older patients in treatment. In our analysis, the patient population, in terms of gender and age, corresponds to those treated in clinical trials. The MPACT study encompassed patients of all ages (range 27–88 years, with a median of 63 years) [18]. In our analysis, the median age was 66 years (range 37–84 years). Patients over 75 years of age comprised only 10% of the study population. The proportion of patients receiving 2nd line of treatment in our analysis compared to the MPACT study was 41% vs. 40%, respectively, with 97% vs. 38% of patients receiving multidrug therapy, and 3% vs. 42% of patients receiving monotherapy. Probably, the significant advantage of more effective multidrug regimens, such as FOLFOX, FOLFIRI, FOLFIRINOX, and liposomal irinotecan + LF, used in our centre in the 2nd line of treatment contributed to the prolonged OS compared to the MPACT study.

The treatment showed a good safety and tolerability profile. In our analysis, grade > 3 AEs were neutropenia (36%), fatigue (28%), anemia (12%), thrombocytopenia (7%) and peripheral neuropathy (4%). Sixty six patients (36%) developed severe neutropenia (CTCAE grade 3) treated with G-CSF. Fifty seven percent of patients had anemia, grade ≥ 2, which was treated with erythropoietin subcutaneously.

In the phase III MPACT trial, the most common grade > 3 AEs were neutropenia, leukopenia, fatigue, peripheral neuropathy, anemia, and thrombocytopenia [18].

The incidence of peripheral neuropathy was a noteworthy difference between these two studies. In the MPACT population 17% of patients experienced grade 3 peripheral neuropathy compared with only 4% of Polish patients in this analysis. The reasons for this are ethnic differences and traditional variations in treatment neuropathy. In the real-world Chinese population analysis, 13% and 20.8% of patients experienced grade 3 peripheral neuropathy [30, 31].

In the MPACT trial, the majority of patients did not require a dose reduction and 71% of the nab-paclitaxel doses were delivered at the starting dose of 125 mg/m2. In our analysis in 100% of patients the starting dose was 125 mg/m2. Adverse events of grade ≥ 3 were effectively treated with dose reductions and delays. Sixty one percent of patients had nab-paclitaxel dose reduction, and more than half of patients had gemcitabine dose reduction.

In addition to assessing the safety and effectiveness of first-line GEM-NAB in real-life patients, we also analysed prognostic factors and their influence on survival in this setting.

Analysis of the influence of baseline characteristics on survival showed that only peripheral neuropathy had the greatest impact on OS and PFS.

The inflammation-based NLR score, identified as a prognostic factor for OS and PFS in patients receiving GEM-NAB in pivotal studies [17] and real-life practice [29, 32], influenced OS and PFS for our patients. In mPC, a proinflammatory status of the tumour results in worse prognosis, and therefore, influences treatment response and consequently, survival. Finally, the antigen CA 19.9 significantly influenced OS but did not reach the significance threshold in the PFS analysis.

Therefore, in accordance with the results of the MPACT trial, our study confirmed both serum levels of CA 19.9 and NLR as outcome predictors in patients with mPC.

Mechanical jaundice before treatment significantly influenced PFS, but did not reach the significance threshold in the OS analysis. The time of initiation of first-line treatment has significantly influenced OS, which includes introducing the need for immediate initiation of treatment. The results also indicate that 2nd and 3rd lines of treatment influenced OS.

Other factors, such as age, gender, ECOG, did not significantly influence either OS or PFS. This finding is particularly controversial for age, which has been identified as a major prognostic factor for all patients with mPC [33], and was subsequently confirmed for patients treated specifically with GEM-NAB [17]. As in previous analyses of real-life patients [29], stratifying patients according to the baseline ECOG score of 0–1 or > 1, shows an influence of ECOG on OS. In our analyses, most patients, 94%, had a baseline ECOG of 0.

The prognostic factors identified in our cohort allowed us to develop models for predicting survival of real-life patients treated with first-line GEM-NAB (Tables 6, 7). In addition to determining the effect of individual regressors on the survival, the estimated models confirm that it is much harder to model PFS than OS. This is indicated, for example, by the higher determination coefficient of the models. Whereas for the OS model the R2 amounted to 0.794 however, the R2 was only 0.16 for PFS in the best case.

Conclusions

Patients enrolled in clinical trials do not always fully mirror the characteristics of a real-life population. Thus, each oncological treatment needs to be assessed in daily clinical practice. Our results confirm the activity, efficacy and tolerability of GEM-NAB as standard first-line treatment in patients with mPC. Although PFS and OS are related to the same patients, the same cases, for better modelling of PFS it is necessary to seek for additional factors that could improve the goodness of fit of the model. Among the factors having the greatest impact on OS was 3rd line of treatment, and for PFS: the presence of peripheral neuropathy.