Case report

A 54-year-old hypertensive male patient underwent aortic valve replacement with a size 21 St Jude Medical Trifecta aortic bioprosthetic valve (St. Jude Medical, Inc., St. Paul, MN, USA) via ministernotomy for severe AS in 2012. Despite adequate counselling at the time of this index procedure, he insisted on a bioprosthesis since he did not want to live with anticoagulation. After suffering a minor cerebrovascular accident (CVA), diagnosed as an acute infarct in the left posterior cerebral artery territory, he recently presented with incidental detection of prosthetic valve degeneration causing moderate aortic stenosis (AS) and moderate aortic regurgitation (AR).

The echocardiogram revealed a degenerated prosthetic aortic valve with a peak and mean gradient of 95 mm Hg and 54 mm Hg and AR (5 mm vena contracta) with an aortic annulus measuring 19 mm. The ejection fraction was 60%.

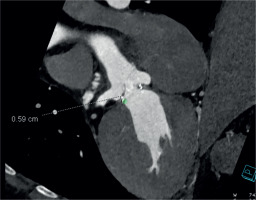

A computed tomography (CT) aortogram analyzed by 3Mensio software revealed an annulus of 20 mm and a sino-tubular junction of 26 mm. The coronaries were disease-free, and the coronary heights were 5.9 mm and 5.3 mm for the right coronary artery (RCA) (Figure 1) and the left main (Figure 2) respectively. These anatomical characteristics, in the presence of a degenerated valve prosthesis at his young age, precluded the option for a transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). His current body mass index (BMI) and body surface area (BSA) were 25.5 and 2.05, respectively. The calculated EuroSCORE for the patient was 1.53%.

A redo median sternotomy was performed. Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) was initiated via a high aortic cannulation and single-stage right atrial cannula. A right upper pulmonary vein vent was inserted followed by a high transverse aortotomy after cross-clamping the aorta. Antegrade ostial cardioplegia was delivered via a Medtronic floppy cardioplegia cannula. After explantation of the degenerated bioprosthesis, a medium-sized sutureless Perceval valve (Corcym S.r.l., Saluggia, Italy) was deployed using the Oldenberg snugger technique after calculating the BMI and BSA, which were 25.5 and 2.05 respectively. We confirmed that the coronary ostia were clear, by introducing the soft-tipped ostial cardioplegia cannula. CPB was weaned off, after routine aortic closure. The CPB time and cross-clamp time were 74 and 54 minutes, respectively.

The patient was extubated on postoperative day 1. After an uneventful postoperative period, he was discharged on day 5. During the 3-month follow-up, the patient was clinically stable, and the echocardiogram indicated a mean gradient of 9 mm Hg across the prosthetic valve causing no patient prosthesis mismatch.

Discussion

There is considerable interest in the lifetime management of aortic valve disease, as younger patients choose bioprostheses at an early age to avoid a life on anticoagulants. This, however, creates the necessity for a second or even third procedure in their lifetime. These repeat procedures could be in the sequence of a (i) surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR)-SAVR-TAVR, (ii) SAVR-SAVR-SAVR, (iii) SAVR-TAVR-TAVR, or (iv) SAVR-TAVR-SAVR.

Logic suggests that the final (often third) procedure, in older patients, will almost inevitably be a TAVR. The dilemma, therefore, centers around the choice of the second procedure.

Placing a TAVR as the first reintervention in a degenerated bioprosthetic valve is technically feasible, but fraught with risks such as high gradients, potential coronary obstruction, leaks, and comparatively earlier degeneration. The TAVR also does not lay an optimal ground for a subsequent TAVR. TAVR as a first reintervention procedure would, counter-intuitively, lead to a SAVR with explantation of the TAVR, if a second reintervention was required, i.e. a technically difficult procedure in an even older patient, associated with significant mortality. In a study by Hawkins et al., SAVR after TAVR was found to be associated with a mortality of 17% compared to SAVR after SAVR, which stands at 9% [1]. The other option would be a valve in valve (ViV) TAVR with its attendant “Russian doll or Matryoshka effect”, higher rates of thromboembolism, paravalvular leaks, and high gradients.

In contrast, a redo SAVR, as a first reintervention, would offer a durable solution with excellent outcomes and low complication rates, as demonstrated by Narayan et al. [2]. A meta-analysis of redo SAVR versus ViV TAVR followed for 5 years showed that, although ViV TAVR was associated with significantly lower mortality within 30 days, this advantage disappeared between 30 days and 1 year and reversed in favor of redo SAVR at 1 year after the intervention [3]. A propensity-matched study showed that the outcomes of a redo SAVR are durable [4], making this option the preferable second procedure when a third valve replacement is anticipated. A small subset of patients may choose to entirely exit the bioprostheses journey and revert to the choice of a mechanical valve.

If biological SAVR is chosen over TAVR as a second procedure, the choice of prosthesis at this point gains importance. It must have the following features:

Should not obstruct the low coronary ostia, during the redo SAVR;

Have a better expandable ring, for future ViV;

Have leaflets which do not have a high potential to obstruct the coronaries;

Leave a high valve-to-coronary (VTC) distance;

Provide a potentially high valve-to-sinotubular junction (VTSTJ) distance after a future TAVR.

The most appropriate valve option, for degenerated bioprostheses requiring redo SAVR, remains a subject under investigation. Newer stented bioprosthetic valves, e.g. the INSPIRIS RESILIA aortic bioprosthesis (Edwards Lifesciences LLC, Irvine, CA, USA), have been designed with dilatable rings, to facilitate a future ViV. At redo, however, the annulus of the aortic valve is often severely stiff, narrowed, and calcified, which makes the suturing of an adequately sized stented prosthesis challenging [5]. A sutureless alternative would avoid this issue. Due to their ease of implant and their design, which maximizes the effective orifice area, the sutureless Perceval rapid deployment valve may have a significant advantage compared to a conventional aortic valve prosthesis [6] in these cases. The use of the Perceval valve for redo aortic valve surgery has been reported with excellent results in multiple case reports [5, 7, 8] and international registries [9]. The Perceval has also been successful in challenging redo situations, and even via the minimal access route, as reported by Paparella and De Santis [10]. During any ViV TAVR, leaflets of a bioprosthetic AVR become pinned in an open position by the stent frame, creating a “virtual skirt” with potential for coronary occlusion or sinus sequestration [11]. Hence, anatomical conditions such as a small annulus, coronary heights and sinotubular junction (STJ) dimensions, which could preclude a future TAVR within conventional stented bioprostheses, gain significance [12, 13].

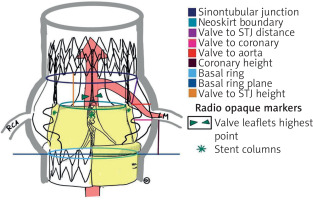

It has been shown that a patient with a VTC distance ≤ 4 mm is at an increased risk of coronary obstruction, and a cutoff of ≤ 3 mm is considered high risk [14]. The Perceval valve’s unique design (Figure 3) incorporates a minimal VTC and VTSTJ distances of 4 and 2 mm, respectively, due to its inherent design of 6 sinusoidal struts and three straight commissural struts. The Perceval pericardial leaflets, though taller, are located intra-annularly, mounted within the vertical commissural struts. VTC is thus not “virtual” but a geometrical characteristic of the prosthesis corresponding to the distance between the vertical struts and the outermost bulge of the sinusoidal struts. When stented valves are fractured, they may expand by up to 2–4 mm (5 mm VTC distance is considered as a minimum safety margin). The Perceval valve, instead, is not fractured, but thanks to its nitinol stent can by design be overexpanded up to 2.5 mm for each given size. Moreover, this expansion is even and circumferential, in contrast to what can be obtained by fracturing a stented bioprosthesis. Its design helps retaining the VTC distance, as both the vertical struts and sinusoidal struts participate equally in the expansion. In their series of 32 cases, Concistrè et al. never had to manage a coronary obstruction or plan a coronary ostia protection strategy [15].

The high success of ViV in Perceval, with both balloon-expandable and self-expandable valves, is achieved through meticulous attention to numerous technical details [16, 17]. Several radiopaque markers on the Perceval prosthesis can clearly show the transcatheter heart valve (THV) landing zone, the height and dimensions of the stent, the aortic root anatomy, and the final degenerated pericardial leaflet position and height. These could even permit a completely no contrast medium procedure from CT scan planning to THV implantation.

Our 54-year-old patient came for his second intervention 12 years after the first ministernotomy AVR with a Trifecta valve. The Trifecta valve, itself, is not ideal to house a TAVR since the externally wrapped taller pericardial leaflets make it prone to coronary obstruction. Besides VTC distance and coronary heights, stented bioprostheses with externally mounted leaflets are proven independent risk factors for coronary obstruction [13]. His young age, and smaller annulus, both made him less than ideal for a ViV TAVR.

In addition, he had very low coronary heights. This became the second issue in choosing a SAVR valve which would still permit a TAVR at a later stage. Many post SAVR patients have reduced coronary heights due to supra-annular valve seating at the first operation, as explained by Coti et al., who compared post-SAVR coronary heights using CT scan analysis [18]. The study showed a significant reduction in the coronary height in relation to the bioprosthetic sewing ring in 3 different sutured biological prostheses compared with that in rapid-deployment valves. They inferred that sutured prostheses were mostly implanted using 10–15 pledgetted sutures, which may distort the aortic root anatomy and further approximate the coronary ostium to the annular plane. In contrast, the rapid-deployment valve requires only 3 anchoring sutures, without the necessity of any pledget material. More recently, Kawamura et al. investigated the changes in the aortic root through CT-scan assessment after implantation of stented and sutureless and rapid deployment valves [19]. Their analysis showed that coronary heights and sinus of Valsalva diameters were decreased significantly after SAVR, especially in the sutured valve group, and were relatively preserved in the rapid-deployment/sutureless valve group, suggesting a potential advantage of these valves for future ViV. Predictably, implantation of a routine stented bioprosthesis would further reduce the coronary height, and a future TAVR would need a time-consuming BASILICA, chimney procedure [20] or the use of a Shortcut device for satisfactory deployment.

An additional point in favor of a redo AVR with a sutureless Perceval valve is that the type of original valve (bicuspid or tricuspid) is largely irrelevant. Once the native valve (whether bicuspid or tricuspid) has been excised and replaced with a prosthesis, at the first SAVR, it essentially creates a circular ring. This removes any significant anatomical differences (e.g. varieties of bicuspid valves) that might have existed in the original valve structure, which would have been contraindicated for a Perceval implant.

The patient’s postoperative recovery was excellent, with no evidence of any coronary or conduction disturbances. These advantages, along with the assured VTC distance provided by the Perceval frame, create an ideal landing zone for a future TAVR should the need arise. We have no medical indication to perform a CT analysis at this point, but one would of course be done if and when he needs a TAVR.

In conclusion, the lesson from our experience is that when a bioprosthesis degenerates early in a young patient, then a sutureless Perceval valve might be the preferred option for a redo SAVR. It makes the procedure itself easy, is relatively free of coronary height limitations, and provides inherent protection of the coronary ostia in case a future TAVR is needed.

Conclusions

In the lifetime management of AS, invariably the last procedure is the TAVR and the first procedure is usually the SAVR, and so the main dilemma seems to be the choice of the second procedure. From this single case experience, the sutureless Perceval valve seems to be a one-stop solution to address the challenges of coronary heights, annular dimensions, and ease of implantation.