Introduction

Asherman syndrome (AS) or intrauterine adhesions (IUA) is/are defined as the complete or partial obstruction of the uterine cavity. It results from the endometrial injury and destruction of the basal endometrium resulting in/leading to loss or dysfunction of residual stem/progenitor cells in the basal layer [1]. Formation of intrauterine adhesions is multifactorial with multiple predisposing and causal factors. Pregnancy-related intrauterine surgery is the most important predisposing risk factor and has been reported in up to 91% of IUA cases [2]. However, it can also develop after gynaecological procedures or genital infection [3]. The prevalence of AS among subfertile women varies significantly, ranging 2.8–45.5%, depending on the specific subpopulation [4]. Most common clinical manifestations of IUAs are menstrual disturbances, amenorrhoea, recurrent pregnancy loss or infertility [5].

Treatment of choice for this condition is hysteroscopic adhesiolysis. However, the significant clinical challenges related to IUA remains/relate to a high recurrence rate of adhesions, particularly medium to severe ones. This recurrence occurs in up to 20–62.5% of cases, regardless of the surgical procedure [6]. In addition, even if the uterine cavity is reconstructed, endometrium remains thin and the pregnancy rate remains low [7]. So, in addition to adhesiolysis, two crucial strategies are essential: first, placing an intra-uterine barrier to prevent contact on the wounded wall and new adhesion formation; second, utilising medication that enhances endometrial thickness and promotes angiogenesis. Different intra-uterine barriers have been utilised including hormone therapy, intrauterine device placement, Foley balloon catheter, auto-cross-linked hyaluronic acid, and chitosan with varying results [8–10]. Xiong et al. [11] have reported that oestrogen performed better than other measures in preventing IUA recurrence. Vitale et al. [12] have suggested that cross-linked hyaluronic acid gel, with or without a copper intrauterine device as the most effective approach for prevention of IUA. Nevertheless, these agents fail to restore the endometrial function. Recently many articles have reported positive effects of stem cell therapy on the refractory endometrium in AS [13].

Adult stem cells are the progenitor cells that can differentiate into any cell line. Evidence has shown that it is found abundantly in the human body and has demonstrated the ability to enhance endometrial function by releasing anti-inflammatory cytokines and growth factors. This effect occurs either through direct secretion or via extracellular vesicles [14]. So, to assess the clinical effectiveness of stem cell therapy in terms of enhanced endometrial thickness, improved menstrual flow and pregnancy outcomes and providing guidance for future clinical management, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the studies that used stem cells for the management of AS.

Material and methods

Data source and search strategy

We (SJ, PP, VCJ) performed systematic literature search in PubMed, Embase and Google Scholar databases from inception to June 2024. Search was done using key words and Medical Subject Heading terms (AS, intrauterine adhesion, thin endometrium) and stem cell therapy. No restriction for study design, publication date or any other restrictions were applied. Duplicate studies were removed using Rayyan. In addition we checked the reference lists of selected articles to ensure all the eligible studies get included in the analysis.

Selection criteria

Study design: We included pre- and postintervention studies. We excluded case reports, conference abstracts, articles without full texts and studies with animal trials.

Participants: Women with primary or secondary infertility of the reproductive age group (aged 20–50 years) with AS (Grade I–IV) not responding to standard treatment (hysteroscopic adhesiolysis and hormonal therapy)

Intervention: Studies were included if they evaluated stem cell therapy.

Outcome: Primary outcome included pregnancy outcome and change in the endometrial thickness whereas secondary outcome included improvement in menstrual pattern.

Endometrial thickness was evaluated using transvaginal sonography, measured at baseline (before intervention) and then at 3rd, 6th and 9th month postintervention.

Pregnancy rate was defined as s a human chorionic gonadotropin level of > 5 mIU/ml confirmed by a positive pregnancy test or clinical detection after intervention per treated woman.

Menstrual improvement was defined as increase in the amount or duration of flow from baseline.

Two investigators (SS, ShJ) independently evaluated potential articles based on their titles and abstracts using Rayyan [15]. Then the full texts of potentially eligible articles were assessed based on the above-mentioned inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreement between the two investigators were discussed with SJ until final consensus was reached.

Data extraction

Data extraction from the eligible studies was performed independently by two investigators, SJ and VCJ. Extracted data included:

description of the study: author, year, participants, inclusion criteria and follow-up duration,

participant details: age, year of infertility, symptoms, previous treatments, prior treatment outcome and IUA grade, follow-up duration,

intervention details: source of mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), type of MSCs, amount of MSCs, site of transplantation, post-operative hormonal therapy,

outcome measures: pregnancy outcome, change in menstrual volume and endometrial thickness.

Risk of bias

Risk of bias of the included studies was assessed using Quality Assessment Tool for Before-After (Pre-Post) Studies with No Control Group [16]. The checklist includes 12 items and assesses for potential risk for selection bias, information bias, measurement bias, or confounding bias. Two investigators (SJ, VCJ) evaluated the studies for potential risk of bias according to the checklist. Any disagreement was subjected to the third reviewer (PP) for final decision.

Statistical analysis

For the pregnancy rate, the risk ratio (RR) with 95% CI had been calculated for each individual study. To measure the effect size for change in endometrial thickness, standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI was calculated and for menstrual flow, the RR with 95% CI had been calculated for each individual study. Then the data were pooled using a random-effects model. Heterogeneity was evaluated with the I2 test which is expressed as a percentage variation across studies and I2 > 50% was considered as significant heterogeneity. All analyses were performed using the command metanalysis in MedCalc (13.01.15, Belgium). Subgroup analysis was also performed based on the follow-up period.

Result

Search result

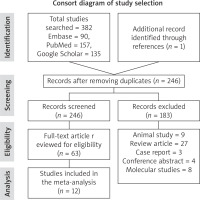

We identified 382 studies from our constructive search strategy. 137 studies were removed as duplicate. 246 studies were evaluated for the relevance to the objectives of the study, out of which183 were removed. 63 studies were re-evaluated for the suitability for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Finally, 12 studies were included for the meta-analysis and review. The detailed study selection process is demonstrated in Figure 1.

Study characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the included studies are described in Table 1. The included studies were published in 2014–2023. All enrolled studies were non-controlled trials. Most of the studies (50%) were from China [17–22], 25% from India [23–25], one from Spain [26], one from Korea [27], and one from Turkey [28]. In total, data of 137 patients were analysed. Most of them had failed to conceive after conventional therapy (hysteroscopic adhesiolysis with intrauterine device (IUD) placement or hormonal therapy).

Table 1

Baseline characteristics of the included studies

Table 2 describes the details of intervention done in the included studies. 6 studies used bone marrow- derived stem cells [18, 23–26, 28], 3 studies umbilical cord-derived stem cells [19, 21, 22], 2 from menstrual blood [17, 20], and 1 from adipose tissue [27]. Stem cells were injected at the sub-endometrial layer, uterine cavity or trans-myometrial/used trans-myometrial transfer. One study used intra-arterial injection of stem cells [25]. All studies had used post-operative hormonal therapy extending 3–12 weeks except for 2 studies [21, 22]. The follow-up period ranged from 1–60 months.

Table 2

Details of interventions done in the enrolled studies

Risk of bias

Included studies were evaluated for risk of bias using National Institutes of Health quality assessment tool for before-after (pre-post) study without control group [16]. Table 3 describes the 12 parameters used for evaluation of enrolled studies. Overall, all the studies were rated as good quality except for few parameters (sample size and blinding of assessors).

Table 3

Quality assessment of the enrolled studies

Publication bias

Results of Egger’s and Begg’s tests showed a risk of publication bias in endometrial thickness after treatment (Egger: p = 0.01, Begg: p = 0.03), pregnancy rate (Egger: p = 0.02, Begg: p = 0.01) and menstrual function (Egger: p = 0.01, Begg: p = 0.03)

Meta-analysis of outcome

Endometrial thickness

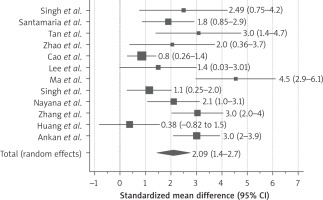

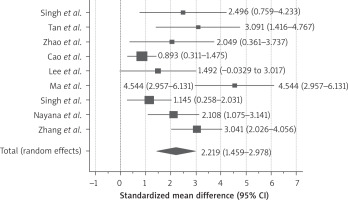

All included studies recruited the patients with failed conventional therapy (hysteroscopy, IUD and hormone therapy – HT) and persistent thin endometrium after adhesiolysis. In all the studies, patients served as self-control. All of them demonstrated increase in endometrial thickness after stem cell therapy at 3-, 6- and 9-month follow-up as shown in Figure 2. The standardised mean difference was 2.09 (95% CI: 1.4–2.7)

We conducted subgroup analysis according to the months of follow-up. 9 studies had reported 3 months’ follow-up of the patients (Figure 3) and demonstrated increase in endometrial thickness after stem cell therapy, the SMD was 2.21 (95% CI: 1.4–2.9).

Figure 3

Subgroup analysis of thickness change at 3 months

I2 77.51% (95% CI: 57.31–88.16), df = 8, p < 0.0001

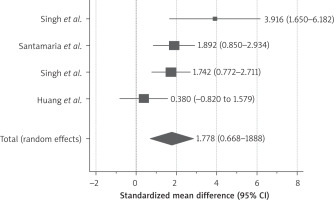

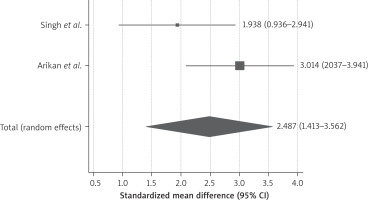

4 studies had reported 6-month follow-up after stem cell therapy (Figure 4), the reported SMD was 1.7 (95% CI: 0.66–2.8). Only 2 studies [24, 28] had reported follow-up till 9 months after stem cell therapy and demonstrated persistence of the stem cell therapy effect on endometrial thickness, as shown in Figure 5, the SMD was 2.48 (95% CI: 1.413–3.562).

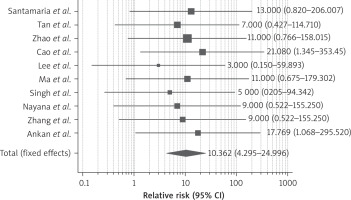

Pregnancy outcome

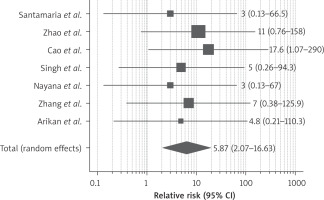

Ten studies reported improvement of the pregnancy rate after therapy. Pregnancy was conceived either naturally or with assisted reproductive technology. As demonstrated in Figure 6, the RR of getting pregnant after stem cell therapy was 9.35 (95% CI: 4.2–24.9) compared to conventional therapy (hysteroscopic adhesiolysis, IUD or HT). We detected no heterogeneity between the enrolled studies (I2 0%, p-value 0.01). 7 studies also reported on the live birth rate; stem cell therapy led to a significant rise in the live birth rate with RR 5.870 (95% CI: 2.071–16.633) as shown in Figure 7.

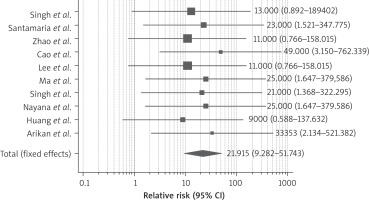

Menstrual function

Ten studies reported menstrual function after stem cell therapy. The results showed that, as shown in Figure 8, administration of stem cell therapy increases the menstrual function as compared to controls. During analysis we counted the event positive if patients had reported improvement in menstrual flow. In addition, the figure indicated no statistically significant heterogeneity among the included trials (I2 = 0%, p-value < 0.0001). However, one study reported that some patients experienced regression of menstruation in the 6 months’ follow-up compared to the first month after receiving stem cell-based therapy [26].

Safety

Five studies reported on the safety profile of stem cell therapy. Tan et al. [17] reported no complications or immunogenic reactions. Similarly, Cao et al. [19] found no surgical complications during surgery, and no inflammatory reactions were detected in endometrial biopsies three months post-surgery. Singh et al. [24] observed no adverse effects in any patients immediately after stem cell instillation or during follow-up. Zhang et al. [21] reported the absence of surgical complications, such as postoperative fever, and no inflammatory reactions were detected via HE staining after transplantation. Huang et al. [22] also noted no adverse effects on the heart, lungs, liver, kidneys, ovaries, blood, or immune system. We could not pool data on safety outcome as studies did not report any uniform and specific side effects of stem cell therapy.

Heterogeneity assessment

Heterogeneity was calculated using Q test. I2 value was 57.31–88.16% for endometrial thickness at 3 months, 22.32–90.28% for embryo transfer (ET) at 6 months and 0–91% for ET at 9 months. We did not detect heterogeneity between the studies for the menstrual function, pregnancy outcome and live birth rate.

Discussion

Primary findings

This meta-analysis included 12 eligible studies with 137 women. All enrolled studies evaluated stem cell therapy in infertile women with AS and failed conventional therapy. In all the studies, patients were taken as self-control. The result demonstrated that stem cell therapy significantly enhanced the endometrial thickness in patients with AS compared to conventional therapy. Stem cell therapy also showed improvement in menstrual flow in most of the patients. Improved endometrial microenvironments resulted in the increased pregnancy rate as well as the live birth rate after stem cell therapy.

Hysteroscopic IUA is widely regarded as the gold standard treatment for patients diagnosed with AS [29, 30]. Following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis, intra-uterine Foley’s catheter or intrauterine devices are commonly employed to minimize postoperative adhesion formation. However, there is limited evidence regarding their effectiveness in preventing the recurrence of IUA and improving subsequent fertility outcomes. Yang et al. [31] have reported that 2 out of 3 women with severe IUA would have recurrence. The primary goal following hysteroscopic surgery is to restore a normal uterine cavity and achieve a functional endometrial layer, particularly for women aiming to preserve or enhance their fertility. As suggested by Verdi et al. [32], severe damage to the basal layer of the endometrium can result in the loss of local endometrial progenitor cells, leading to regeneration failure and adhesion formation. It is now well recognized that cyclical regeneration of the endometrium is likely supported by the proliferation and differentiation of endometrial-intrinsic stem or progenitor cells.

Mechanism of repair of injured endometrium

Stem cells are a unique class of cells characterized by their robust self-renewal capacity and multidirectional proliferation and differentiation potential. These properties enable them to directly induce differentiation and replace damaged tissues, offering significant therapeutic advantages. Grossly, depending on its developmental sequence, stem cells can be embryonic stem cell or adult stem cell. Adult stem cells can be derived from various sources like bone marrow, adipose tissue, human umbilical cord, amniotic membrane and menstrual blood. In this meta-analysis, enrolled studies have used various sources of stem cells like menstrual blood, adipose tissue, bone marrow and human umbilical cord and demonstrated its potential in repairing damaged endometrial tissue. Stem cells primarily repair endometrial injuries through their differentiation capacity, paracrine activity, and immunomodulatory effects. The transplanted stem cells not only directly differentiate into endometrial cells, they also get differentiated into stromal cells and vascular endothelial cells which play a significant role in endometrial repair [33]. In addition, it can regulate expression of various genes in recipient cells involved in repair of endometrium and also influence the immunomodulatory function of endometrium and hence enhancing the implantation and pregnancy rate [34]. Among all included studies, 4 studies have reported on the molecular markers [18, 19, 21, 26]. Santamaria et al. [26] demonstrated that engrafted CD133+ bone marrow-derived stem cells stimulated the secretion of paracrine factors, including thrombospondin-1 and insulin-like growth factor. These factors activated mitosis in surrounding cells, thereby promoting endometrial regeneration. Zhao et al. [18] reported that stem cell therapy downregulated ΔNp63 in endometrium, which regulates its proliferation and differentiation. In addition, Cao et al. [19] demonstrated histologically that stem cell therapy upregulates the expression levels of estrogen receptor α (ERα), vimentin, Ki-67, and vWF (von Willebrand factor). Zhang et al. [21] reported an increase in the expression of Ki-67, ERα, and PR of endometrium after treatment. Ki-67 is a nuclear antigen mainly present in proliferating cells. These findings suggest that stem cell therapy improves the endometrial microenvironment.

All the enrolled studies used oestrogen following stem cell therapy. A high dose of oestrogen is thought to promote proliferation and reepithelization at the injured site [35]. However, oestrogen therapy alone has not been proven to be beneficial in improving the reproductive outcome [36]. This is also evident from all the enrolled studies, wherein all patients had previously failed outcome following hysteroscopic adhesiolysis and oestrogen therapy. So, the majority of the benefits of improved reproductive outcome were contributed by stem cell therapy. This meta-analysis had shown that stem cell therapy is safe and effective in the treatment of AS.

Heterogeneity explanation

We observed significant heterogeneity between the studies for endometrial thickness after the stem cell therapy. This could be due to variation in the sample size, years of infertility, endometrial thickness before and after treatment across the studies. For example, Cao et al. [19] reported SMD for endometrial thickness as 0.89 (95% CI: 0.3–1.4) whereas Ma et al. [20] reported 4.5 (95% CI: 2.9–6.1). Of note, measurement of endometrial thickness is operator dependent and hence might influence the outcome. In addition, all eligible studies recruited an extremely small sample size with only Cao et al. [19] and Arikan et al. [28] having recruited more than 20 patients. Small size is more prone to yield biased result compared to the large sample size and hence producing heterogeneity in the pooled data. We could not perform subgroup analysis due to the small number of eligible studies included for the meta-analysis to find out the significant contributor of the heterogeneity. Hence, results of the pooled data should be interpreted cautiously.

Strengths and limitations

The main limitation of this analysis is the limited number of studies on humans, so we could enrol only 12 studies. All eligible studies were pre- and post-test studies and hence lacked randomization and might have introduced selection bias. In addition, we also noticed publication bias as only the positive result would have been published. Source and dose of stem cells were varied in different studies, however, we could not classify them into subgroups and perform subgroup analysis due to the limited number of studies. The timing and route of stem cell instillation also varied in different studies. Although it was demonstrated that stem cell therapy is beneficial in the treatment of AS, we could not decide on its timing and route of administration.