Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a hematological malignancy characte-rized by the clonal expansion of myeloid progenitor cells, leading to impaired differentiation and the accumulation of blasts in the bone marrow and peri-pheral blood, and can develop either de novo or as therapy-related AML following chemotherapy for malignancies such as lymphoma. A critical factor in the pathogenesis of AML is the transcription factor C/EBPα, which plays an essential role in myeloid differentiation [1–4]. CEBPA is expressed as two isoforms, the full-length p42 and the truncated p30, arising from alternative translation initiation sites. The p42 isoform is crucial for normal granulocyte differentiation, while the p30 isoform acts as a dominant-negative inhibitor, often contributing to leukemogenesis [5–7]. Mutations in the CEBPA gene are found in approximately 10% of AML cases and are associated with a favorable prognosis, particularly when biallelic mutations are present [8–10]. Dysregulation of CEBPA in AML occurs through various mechanisms, including mutations, promoter methylation, and altered expression of its isoforms [11–13]. N-terminal mutations often result in the exclusive expression of the p30 isoform, which lacks the transactivation domain necessary for normal function, contributing to the differentiation block characteristic of AML [14, 15].

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a diverse group of RNA molecules longer than 200 nucleotides that do not encode proteins [16]. They play crucial roles in regulating gene expression through mechanisms such as epigenetic modifications, chromatin remodeling, and transcriptional regulation [17]. Transcribed from non-coding regions of the genome, lncRNAs are classified into eight categories: intergenic, intronic, enhancer, promoter, natural anti-sense/sense, small nucleolar RNA-ended, bidirectional, and non-poly(A) lncRNAs [18, 19]. These molecules are involved in essential biological processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and migration [17, 20]. Dysregulation of lncRNAs is linked to various diseases, particularly cancers, where they can function as oncogenes or tumor suppressors [21–25].

Yu et al. [26] reviewed the expression levels of NEAT1 in various cancers and found that its aberrant overexpression was associated with poor prognosis in many solid tumors, such as lung, esophageal, colorectal, and hepatocellular carcinoma. However, in acute promyelocytic leukemia, NEAT1 was downregulated, correlating with a worse prognosis, as it promoted leukocyte differentiation [27].

NEAT1 exists as a short (3.7 kb NEAT1.1) and a long (22.7 kb NEAT1.2) isoform [28]. NEAT1.1 is involved in modulating gene expression and chromatin dynamics, regulating RNAs such as microRNAs (miRNAs) and mRNAs through sponging or direct RNA-RNA interaction [28, 29]. It is implicated in enhancing chemotherapy effects. Silencing NEAT1.1 in bladder cancer cells enhances the suppression of cell growth and invasion while promoting apoptosis under cisplatin treatment, suggesting its role in chemoresistance via pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin signaling [30]. NEAT1.2 plays a crucial role in the formation and stability of nuclear paraspeckles, subnuclear structures involved in regulating gene expression and cellular stress responses [31, 32]. It acts as a scaffold, enabling the assembly of paraspeckles by organizing proteins and other RNAs within these structures, influencing RNA editing, processing, and the stability and translation of mRNAs [33, 34].

In this study, we investigated how the two CEBPA isoforms, p42 and p30, influence the expression levels of NEAT1 during the differentiation of leukemic cells. By examining the interactions between these isoforms and NEAT1, we aimed to elucidate their roles in leukemogene-sis and differentiation, providing insights into potential therapeutic targets for AML.

Material and methods

TCGA

Data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network, which includes samples from 200 de novo AML patients, were used. This publicly accessible dataset provides comprehensive genomic information, enabling detailed analysis of gene interactions [35]. Our study focused on the interaction between the transcription factor CEBPA and the lncRNA NEAT1 in AML patients. We analyzed the correlation between CEBPA and NEAT1 expression across all AML patients. Subsequently, we categorized the patients into two groups: those with a CEBPA mutation (Mut) and those with wild type CEBPA (WT). In each group, we analyzed the expression levels of CEBPA and NEAT1 and compared the groups to identify any significant differences.

Cell culture

The cell lines K562-C/EBPα-p42-ER, K562-C/EBPα-p30-ER, and K562-ER (control) were provided by Daniel G. Tenen from Harvard University, Boston, MA, USA. Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (without phenol red) supplemented with 10% charcoal-treated fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 1 µg/ml puromycin. The cultures were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Cell differentiation

To induce granulopoietic differentiation of K562-C/EBPα- ER cells, 5 µM β-estradiol (final concentration), dissolved in ethanol, was added. An equal volume of ethanol was used as a control. Differentiation was verified by measuring the surface marker CD11b using flow cytometry. CD11b antibody staining was performed using the manufacturer’s guidelines (130-110-559; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) and was measured in the APC channel of a flow cytometer (BD, FACSCanto II, Franklin Lakes, USA).

Isolation and detection of RNA

Total RNA was extracted using the Machery & Nagel NucleoSpin RNA isolation kit, following the manufacturer’s guidelines (REF 740955.250, Machery & Nagel, Düren, Germany). RNA was isolated from 1,000,000 cells for all experiments. One microgram of total RNA was converted into complementary DNA (cDNA) using the SCRIPT Reverse Transcriptase kit from Jena Bioscience (PCR-505S, Jena Bioscience, Jena, Germany) and random hexamer primers. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed to quantify the expression levels of NEAT1.1 (thermofisher assayID: Hs03453535_s1; Cat#:4331182, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) and NEAT1.2 (thermofisher assayID: Hs03924655_s1; Cat#: 4426961, Thermo Fisher Scien-tific, Waltham, USA). GAPDH (forw. 5′CAATGACCCCTTC-ATT-GAC3′; rev. 5′TTGATTTTGGAGGGATCTCG3′) was used as a housekeeping gene for normalization. Expression levels were analyzed using the delta-delta CT method.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software with Student’s t-test, Welch’s t-test and Pearson correlation. The results were presented graphically, with significance indicated. P-values below 0.05 were deemed statistically significant. Each experiment was performed with three biological replicates.

Results

AML patients with mutated CEBPA showed reduced levels of the lncRNA NEAT1

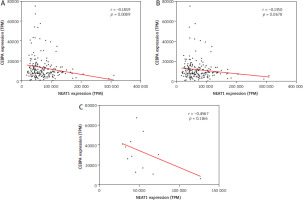

We analyzed the transcriptome data of 200 de novo AML patients in the TCGA database, focusing on CEBPA mutation status and the expression levels of CEBPA and NEAT1. Complete data were available for 197 pa-tients. Initially, we observed a significant negative cor-re-lation between CEBPA and NEAT1 expression levels (Pearson r: –0.1859, p-value: 0.0089, Figure 1A).

Figure 1

Pearson correlations between NEAT1 expression and CEBPA expression in: A) 197 AML patients, B) 184 AML patients with CEBPA-WT and C) 13 AML patients with CEBPA-Mut

To investigate this further, we divided the patients into two groups based on CEBPA mutation status: 184 with CEBPA-WT (Figure 1B) and 13 patients with different individual CEBPA-Mut (Figure 1C) – not all truncated CEBPA. In both subgroups, the correlation between CEBPA and NEAT1 was no longer significant.

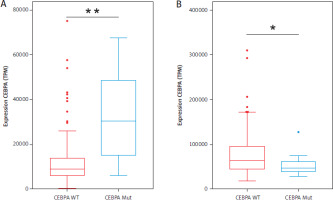

A comparison of the expression levels of CEBPA revealed significant differences between the two groups. Patients with CEBPA-Mut showed almost three times higher CEBPA expression than those with CEBPA-WT, with a p-value of 0.0014 (Figure 2A). In contrast, NEAT1 expression was significantly higher in the CEBPA-WT group, with a p-value of 0.0166 (Figure 2B). These findings highlight distinct expression patterns correlating with CEBPA-Mut status.

Figure 2

Expression levels of AML patients with CEBPA-WT and CEBPA-Mut. A) CEBPA expression and B) NEAT1 expression. 184 AML patients with CEBPA-WT are shown in red, and 13 AML patients with CEBPA-Mut are shown in blue. Significance was tested using an unpaired twotailed Welch’s t-test; **p = 0.0014; *p = 0.0166; TPM – transcripts per million

C/EBPα isoforms regulate NEAT1.1 expression during differentiation in vitro

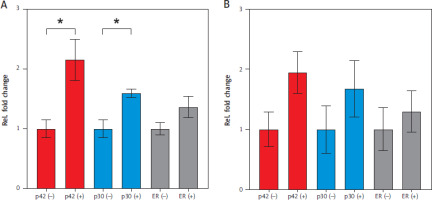

To test the regulation of NEAT1.1 and NEAT1.2 by C/EBPα, we used the K562-C/EBPα-ER cell lines in vitro. After stimulation with β-estradiol, C/EBPα translocates into the nucleus, binds to its target promoters and thus induces differentiation. K562 and K562-ER cells are unable to produce endogenous C/EBPα. As a result, these cells cannot induce C/EBPα- dependent differentiation. In flow cytometry, the differentiation was analyzed using the granulocyte marker CD11b. After 24 h of stimulation, about 40% of the cells were CD11b posi-tive at p42, about 10.5% at p30 and 0% at ER (Supplementary Figure 1). To exclude the possibility that the differences in differentiation were due to different expression levels of CEBPA isoforms, Western blot analysis was performed. There was no significant difference between the untreated cell lines. Nevertheless, an approximately 20% signal reduction of C/EBPα was observed in the K562-C/EBPα-p30-ER cell line (Supplementary Figure 2).

After 24 h of stimulation with β-estradiol, p42 significantly upregulated NEAT1.1 expression by 2.15-fold (p = 0.0363), while p30 induced 1.59-fold upregulation (p = 0.0159) (Figure 3A). In the ER cell line, which produces only the truncated estradiol receptor, no significant regulation of NEAT1.1 was observed. Additionally, the longer isoform NEAT1.2 did not show significant upregulation in any of the three cell lines after 24 h (Figure 3B).

Figure 3

Relative fold change of NEAT1 expression induced by CEBPA isoforms after 24 h. A) Relative fold change in NEAT1.1 expression. B) Relative fold change in NEAT1.2 expression. Results are color-coded: red for CEBPA-p42, blue for CEBPA-p30, and grey for the truncated estradiol receptor ER. Differentiation was induced with β-estradiol (+) and EtOH was used as a control (–). Data represent mean values with S.E.M. from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was tested using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. p-value: p42 p = 0.0363; p30 p = 0.0159

Discussion

In 2016, Yu et al. [26] reported that the lncRNA NEAT1 is a tumor driver in most cancers, with the exception of acute promyelocytic leukemia, in which NEAT1 acts as a tumor suppressor. NEAT1 has also been implicated in the Wnt signaling pathway [36–39]. In AML stem cells, NEAT1.1 is released from the nucleus into the cytoplasm, where it interacts via the E3 ubiquitinase Trim 56 and the Wnt component DVL2 to inactivate the Wnt pathway [39]. The release of NEAT1.1 from the nucleus into the cytoplasm in AML stem cells is regulated by the nuclear protein NAP1L1 and the transcription factor C/EBPβ [40]. Since CEBPB and CEBPA belong to the same family of transcription factors and CEBPA is known to be mutated in about 10% of de novo AML cases, we wanted to investigate whether CEBPA also influences the regulation of NEAT1 [41, 42].

Using the TCGA database, we identified a slight but significant negative correlation between CEBPA expression and NEAT1 expression in de novo AML patients [35]. The limitation of the database did not allow us to distinguish between the different isoforms of CEBPA and/or NEAT1. However, we were able to divide the AML patients into a group with CEBPA-WT and a group with CEBPA-Mut. The 13 individual CEBPA mutations were grouped for statistical analysis. In both groups, we could no longer detect any significant correlation. Nevertheless, based on the negative correlation, we suspected regulation of NEAT1 by CEBPA, which we investigated further.

When comparing the two patient groups, we found that CEBPA mutated AML patients expressed significantly less NEAT1. Gene regulation in AML can therefore be directly influenced by mutations in CEBPA, but can also be influenced downstream by NEAT1, as NEAT1 itself is also involved in gene regulation [29]. This makes NEAT1 an interesting target for new AML therapies, as the restoration of normal NEAT1 expression could lead to normal differentiation of myeloid blasts.

In the cell lines U937 and NB4, which both produce endogenous C/EBPα, NEAT1 was found to have promo-ter sites that can bind C/EBPα [43]. Therefore, we used the cell line K562, which does not produce endogenous C/EBPα, in our in vitro experiments. By selective over-expression of the two C/EBPα isoforms p42 and p30, we were able to investigate their direct influence on the expression of NEAT1.1 and NEAT1.2. We assumed an equal expression level of both C/EBPα isoforms. No significant difference in C/EBPα expression was detected between the two untreated cell lines in Western blot analyses. The approximately 20% reduction in signal intensity observed in the p30-expressing cell line was most likely due to the lower number of antibody binding sites accessible to the truncated C/EBPα isoform. In this model, C/EBPα p30 represented the mutated CEBPA, although in vivo not all mutations in CEBPA automatically lead to truncation of CEBPA-WT [44–46].

The expression of NEAT1.1 was significantly upregulated more than twofold by C/EBPα p42-induced diffe-rentiation. C/EBPα p30-induced differentiation regulated NEAT1.1 at only about 50% of the p42 level. The critical regulatory region for cell proliferation and differentiation is located at the N-terminal end of CEBPA. This was shown in a study in which the N-terminals of CEBPA and CEBPB were exchanged in chimeric proteins. This study showed that C/EBPα upregulates the expression of genes that control the cell cycle, differentiation, and apoptosis [47]. One consequence of reduced C/EBPα transactivation is decreased NEAT1.1 expression. As a result, less NEAT1.1 is translocated to the cytoplasm, leading to insufficient inhibition of the Wnt signaling pathway and, consequently, increased cellular proliferation [40].

Differences in the regulation of lncRNAs by the two C/EBPα isoforms have also been identified. In the case of the lncRNA urothelial carcinoma associated 1 (UCA1), both C/EBPα isoforms bind to the promoter, but the expression of UCA1 is regulated with opposite effects [48]. P42 leads to downregulation and p30 to the upregulation of UCA1. In AML patients with a biallelic CEBPA mutation, higher expression of UCA1 was observed compared to AML patients with CEBPA-WT [48].

Compared to NEAT1.1, the expression of NEAT1.2 was slightly weaker and not significantly regulated by both isoforms of C/EBPα. Since paraspeckles are part of trans-criptional control, it is reasonable to assume that key components such as NEAT1.2, which form the scaffold of paraspeckles, are upregulated during differentiation [31, 49]. In addition, NEAT1.2 is also involved in splicing and mRNA processing through interaction with RNA binding proteins such as NONO and SFPQ [50, 51].

Conclusions

The data show that the expression of NEAT1 in AML cells can be regulated not only by CEBPB, but also by CEBPA and in particular by the CEBPA-WT isoform p42. Even tiny differences, such as truncation of the CEBPA transcription factor, can induce differentiation to varying degrees in vitro. It remains to be clarified which CEBPA isoform can bind to which promoter of NEAT1 and whether this could be one reason for the lower expression of NEAT1 in CEBPA p30 differentiation [43]. Overall, our work shows that NEAT1 is influenced by CEBPA in AML.