Introduction

Implanted venous ports have become widely used in cancer patients [1, 2]. However, placing this auxiliary device carries a risk of complications [3–6]. Delayed complications include infection, catheter thrombosis, vessel thrombosis and stenosis, displacement of the catheter tip due to shoulder movements, catheter fracture with extravasation, or fracture with migration or embolization of catheter material [3–6]. A rare complication, so-called pinch-off syndrome, which is a spontaneous event, refers to a disconnection of the catheter port from the injection port, exceptionally rarely to its rupture at the connection point or during removal of an unnecessary or infected system [7–23] with subsequent migration of the catheter into the right atrium [16, 18], right ventricle [21, 22] or pulmonary arterial bed [9, 14, 17, 18, 20]. The symptoms and consequences of venous port catheter migration have been described in a number of studies [7–23] and all the investigators emphasize that the most common presentation of central venous port-catheter dislodgement is resistance during flushing, although the presence of a catheter tip in the right ventricle may be associated with the occurrence of arrhythmia [7] or palpitations and chest discomfort [23]. For the removal of catheters with their tip in the superior vena cava or in the right atrium, the femoral access using a lasso loop is usually used, whereas goose neck snares, pigtail catheters and stone basket catheters are used individually or in combination [10–13, 16, 18, 21, 22]. Both lasso loops, goose neck snares, and stone basket catheters are straight catheters thus impeding precise maneuvering in the right ventricle or pulmonary arteries, therefore pigtail catheters are used as auxiliary tools to help position the grasped port catheter in a convenient location or move it to the right atrium [9, 14, 17, 18, 20]. The usefulness of curved catheters equipped with a hemostatic valve has not been described, the possibility of using upper/subclavian access for maneuvering lasso or goose neck snare catheters in the pulmonary arteries has not been described, either, and the removal of the grasped port catheter through the site of tool entry into the venous system has only been marginally considered (there is a real possibility of cutting the catheter).

Aim

The aim of the study was to describe 4 cases of removing venous port catheters dislodged into the pulmonary circulation using various techniques and tools designed to remove migrating fragments of broken intracardiac leads [24, 25].

Methods

Study population

The 4 patients with a pulmonary artery venous port catheter were selected from a group of 111 people undergoing transvenous catheter extraction (TCE) procedures (removal of 71 dialysis catheters and 40 venous ports) at a TCE reference center between February 2015 and January 2025. The selection of patients was spontaneous. In all patients with venous ports referred for their removal, there were only 4 cases of pinch-off syndrome, i.e. disconnection of the catheter from the injection capsule (3 cases) or rupture of the port catheter in the area of the injection capsule (1 case). In all 4 patients, the port catheter moved spontaneously (with the blood stream) to the pulmonary circulation. Registry data were entered prospectively and analyzed retrospectively.

Approval of the Bioethics Committee

Retrospective analysis of medical patient records was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and after receiving final approval from the Bioethics Committee in Lublin no. 288/2018/KB/VII. Before the procedure all patients signed informed consent to anonymous processing of their results/tests and agreed to be contacted by phone to obtain information about their health.

Results

Basic patient data are summarized in Table I.

Table I

Basic patient data

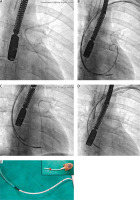

Case 1. A 52-year-old woman with a venous port implanted 7 years ago as part of treatment for gallbladder cancer (surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy). The treatment was effective. The initial port removal was incomplete due to catheter fracture at the point of entry into the venous system. For 2 years the patient had been experiencing various nonspecific chest complaints (palpitations, episodes of dyspnea, unclear discomfort). Radiographic examinations revealed the cause of the problem (Figure 1 A).

Using a pigtail catheter via the femoral approach, a guidewire was introduced into the pulmonary trunk (Figure 1 A) followed by a “lasso” assembly (Figure 1 B), and the end of the catheter was grasped (Figure 1 C). The grasped port catheter was pulled down to the femoral vein (Figures 1 D, E). Due to unequal diameters of the port catheter and the lasso catheter, and due to concerns about cutting the catheter or damaging the femoral vein, a set of catheters designed to facilitate extraction of intracardiac electrodes was used to guide the port outward (Figures 1 E, F). The patient remains in good health, working as a neurosurgical nurse.

Case 2. A 22-year-old man with a venous port implanted 2 years ago during treatment for lymphoma (Th3-Th6 spinal canal tumor) with effective aggressive chemotherapy and radiotherapy. During removal of the no longer needed port system, the catheter was fractured near the injection port and the broken port catheter spontaneously moved deeper into the venous system and then to the pulmonary artery. Several weeks after a failed attempt of removal the patient was referred to the TCE center. Radiographic examinations revealed the location of the port catheter with the proximal end of the catheter pinned to the pulmonary valve (Figure 2 A). To facilitate maneuvering in the pulmonary circulation and right ventricle, the left upper access (natural curvature of the catheter path) was used (Figures 2 B). First, the pigtail catheter and twisting technique [24, 25] were used to free the proximal end and move it to the right ventricle (Figure 2 B). To guide insertion of the pigtail catheter and lasso catheter, catheters designed for implantation of coronary sinus leads were used as the steering catheter (Figures 2 B–D). The broken port catheter was then grasped with the lasso catheter (Figure 2 C), which was removed together with the other catheters (Figure 2 D). The internal diameter of the catheter for implantation of coronary sinus leads was sufficient for safe removal of the port catheter through the venous entry site (Figure 2 E).

Case 3. A 44-year-old man with a venous port implanted 2 years ago as part of treatment for colon cancer (surgery, chemotherapy). The treatment was completed, and the port was regularly flushed. During the last check-up, resistance to flushing was felt. An attempt was made to remove the unnecessary port, but after opening the pocket, no catheter was found. The unnecessary injection port was removed (Figure 3 A). Radiographic examination revealed the location of the catheter in the pulmonary circulation; the proximal end was found in the pulmonary trunk and the distal end was looped in the lower lobar artery (Figure 3 A). For easier maneuvering in the pulmonary circulation and the right ventricle, a left upper access (natural curvature of the catheter path) (Figure 3 B) and a catheter designed for implantation of coronary sinus leads were used (Figures 3 B–F). The catheter has a soft flexible atraumatic tip and a hemostatic valve. The catheter lasso was used to grasp the port catheter (Figure 3 C) and they were both removed through the 12F introducer sheath (Figures 3 D–F).

Case 4. A 66-year-old woman with a venous port implanted 3 months ago during breast cancer treatment (surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy). The initially successful treatment was continued. But dysfunction of the port system was noted during flushing and a leakage between the injection port and the catheter was suspected. Radiographic examination confirmed the catheter pinch-off syndrome and prevented unnecessary search near the injection port (Figure 4 A). The patient was referred to the TCE center. Due to the location of the obstruction, a catheter for implantation of coronary sinus leads (Figures 4 B–E) was used as a steering/working catheter via the femoral access. It was possible to slide the lasso catheter onto the proximal part of the port catheter from below (Figures 4 B, C) and remove the port catheter through the femoral access. The procedure was performed under the control of transesophageal echocardiography to avoid damage to the heart structures. In the next step, the injection port was removed and a new port was implanted to continue chemotherapy.

Discussion

“Spontaneous” disconnection (obstruction due to a clot or sharp kinking plus injection-induced overpressure) of the catheter from the injection port, rupture of the port during an unsuccessful attempt at removal may lead to migration of the port catheter into the venous system [6–23] and sometimes into the pulmonary circulation [9, 14, 17, 18, 20]. This problem was addressed in single case studies [7, 8, 14, 16, 18, 20–24], case report series [15, 17, 19] or larger research on migration of disconnected venous port catheters [9–13]. The investigators describe the most common techniques: femoral access, goose neck snares, pigtail catheters and stone basket catheters used individually or in combination [10–13, 16, 18, 21, 22] and pigtail catheters used as auxiliary tools. It should be emphasized that there are no tools designed to remove venous port catheters from the circulatory system. The removal of dislodged venous ports is usually performed by interventional radiologists using tools they are familiar with. The complication is somewhat similar to migration of torn intracardiac leads [25, 26] suggesting that some techniques and tools used in interventional cardiology may also be useful (“spaghetti twisting technique”, use of catheters for implantation of left ventricular leads, methods for removal of foreign bodies through the venipuncture site, etc.). We have presented 4 cases of removing venous port catheters from the pulmonary circulation performed by a cardiologist. It is noteworthy that all procedures, similarly to extraction of intracardiac leads, are performed under the control of transesophageal echocardiography. Procedures are performed looking at a flat fluoroscopic image and the “forward”/”backward” tip is an extremely valuable navigation aid when grasping the catheter end. Similarly, information on pulling on cardiac structures increases procedure safety, not to mention early recognition of bleeding complications.

This is a case series that is intended to demonstrate techniques that may be used to remove venous port catheters from the pulmonary circulation. This study does not address the removal of indwelling, non-removable catheters. Techniques and tools were selected individually in each case always remembering to choose the safest option.

Conclusions

Pinch-off syndrome is a rare complication of venous port catheters. The movement of a disconnected port catheter into the pulmonary circulation creates a troublesome situation and the patient requires admission to the TCE reference center. Transvenous removal of venous port catheters from the pulmonary circulation is possible, effective and safe, but requires experience and a wide range of dedicated and non-dedicated tools. Some techniques and tools designed for removal of intracardiac leads may also be useful.

Data availability

Readers can access the data supporting the conclusions of the study at www.usuwanieelektrod.pl.