Introduction

Minimally invasive surgery has replaced classic general surgery in almost every area, providing many benefits of less invasive approaches [1, 2]. In recent years, cardiac surgery has also seen a significant increase in minimally invasive procedures in the last decade [3, 4]. Minimally invasive aortic valve replacement (MS) has emerged as a significant advancement in cardiac surgery, offering a less traumatic alternative to traditional open-heart procedures [2, 3]. The conventional approach, which typically involves a full median sternotomy (FS), is associated with considerable postoperative pain, longer recovery times, and increased risk of complications such as infections and blood loss [5, 6]. In contrast, minimally invasive techniques, such as partial upper hemisternotomy and right mini-thoracotomy, aim to minimize surgical trauma while maintaining effective surgical outcomes [7, 8]. However, the literature presents mixed findings regarding the mid- and long-term outcomes of MS versus FS methods, with some studies indicating comparable survival rates and complication profiles [9–11]. This suggests that while MS may offer immediate benefits, the mid-term efficacy remains an area of ongoing research and debate.

Aim

The purpose of our study was to determine early and mid-term outcomes of minimally invasive J-shaped hemisternotomy in comparison to fully sternotomy patients with aortic valve disease requiring valve replacement.

Material and methods

Study population and clinical variables

We retrospectively analyzed the cardiac surgical database of patients treated between 2014 and 2024 in the Department of Cardiac Surgery at the Medical University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland. The Institutional Review Board was consulted, and patient consent was waived (PCN/CBN/0052/KB/118/22, 2022-06-15). Initial clinical and procedural data, along with follow-up outcomes, were recorded in predetermined electronic case report forms. Survival status was assessed by the National Health Fund.

The study included 1289 elective patients referred for surgical isolated elective aortic valve replacement (AVR) for severe aortic stenosis and/or insufficiency who underwent MS or FS. Additional procedures such as coronary artery bypass grafting, aortic aneurysm surgery, and mitral or tricuspid valve surgery were excluded. Patients who underwent urgent, emergency, or salvage AVR were also excluded. Assignment to either treatment arm was determined by the multidisciplinary Heart Team after careful consideration. The choice between minimally invasive and conventional aortic valve replacement reflected both surgeon preference and specific patient-related factors, such as experience of the surgeon and anatomical complexity.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was 5-year survival after AVR in relation to the MS and FS access. MS was defined as a minimally invasive partial hemisternotomy, J-shaped, extending to the fourth intercostal space. FS was identified when classic access to the heart with full sternotomy was performed. The 30-day, 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year mortality and survival were also reported.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in R version 4.2.0. We first inspected the patterns of missing data by visual inspection and then applied Little’s MCAR test within clinically coherent blocks of variables. The results indicated that missingness was likely not completely at random (MNAR), and, given the heterogeneity of our dataset and the potential for complex non-linear relationships, we elected not to pursue multiple imputation. Next, we estimated propensity scores for each patient’s likelihood of undergoing a minimally invasive procedure using a logistic regression model that incorporated all key preoperative covariates. Matching was carried out on complete cases only by means of one-to-one nearest-neighbor matching without replacement, using a caliper width of 0.1 standard deviations of the logit of the propensity score. Adequacy of matching was confirmed by ensuring all standardized mean differences were below 0.10 and by passing the Hansen-Bowers global balance test.

Baseline clinical characteristics were compared both before and after matching. In the unmatched cohort, continuous variables were assessed for normality with the Shapiro-Wilk test and then compared by Welch’s t-test if normally distributed or by the Mann-Whitney U test if not. Categorical variables were compared using the χ² test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. In the matched cohort, paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used for continuous variables, and McNemar’s test was applied for categorical variables.

Survival outcomes were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method, with differences assessed by the log-rank test in the full cohort and by the stratified log-rank test in the matched cohort. To quantify the effect of surgical technique on mortality, we fitted Cox proportional hazards models; in the matched sample, these models incorporated a robust sandwich variance estimator clustered by matched pairs. Finally, the relationship between surgical approach and each individual postoperative complication was evaluated using univariable logistic regression in the full cohort and conditional logistic regression in the matched cohort. All regression and survival analyses employed an available-case approach, excluding only those patients who lacked data for covariates included in a given model.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The initial study cohort comprised 1,289 patients, including 1,216 undergoing full sternotomy and 73 in the MS group. At baseline, the groups were largely comparable in terms of preoperative risk and comorbidities. There were no statistically significant differences in median EuroSCORE II (1.24 vs. 1.18; p = 0.134), age (67 vs. 65 years; p = 0.123), or body mass index (BMI) (28.1 vs. 27.8 kg/m²; p > 0.999) (Table I). Similarly, the prevalence of comorbidities did not differ significantly. A key difference was higher incidence of acute coronary syndrome in the MS group (5.5% vs. 0%; p < 0.001). Echocardiographic assessment revealed no significant baseline difference in left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) (median 55% in both groups; p = 0.276). A significant disparity was observed in valve pathology, with a much higher prevalence of bicuspid aortic valve in the MS group (52.2% vs. 34.0%; p = 0.003) (Table II).

Table I

Preoperative characteristics before and after PS matching

Table II

Echocardiographic parameters

Analysis of the unmatched groups revealed longer procedural times for the MS approach. Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) time was significantly longer (median: 71 vs. 63 min; p = 0.005), while the difference in aortic cross-clamp time (median: 55 vs. 50 min; p = 0.064) was not significant (Table III). The incidence of postoperative complications was not statistically different between the groups at baseline despite postoperative bleeding, which was, both before (520 ml vs. 460 ml, p = 0.054) and after propensity score matching (600 ml vs. 460 ml, p = 0.052), lower in the MS compared with the FS group (Figure 1 A, Table IV). One patient required conversion when significant bleeding occurred 4 h after the operation from the musculo-phrenic artery, which could not be controlled from the ministernotomy access.

Table III

Operative characteristics before and after PS matching

Table IV

Outcomes before and after PS matching

Propensity score matching

To minimize selection bias, one-to-one nearest-neighbor matching was performed without replacement, using a caliper width of 0.1 standard deviations of the logit of the propensity score. The propensity score was derived from a logistic regression model which showed good discriminative ability (AUC = 0.645).

From an initial cohort, the procedure yielded 65 matched pairs. Seven patients (3 FS, 4 mini-AVR) were excluded from the propensity score model due to missing data in key covariates. After matching, excellent covariate balance was achieved. All standardized mean differences (SMDs) were reduced to below the recommended 0.1 threshold. The overall balance was confirmed by non-significant results from global multivariate tests, including the Hansen-Bowers test (p = 0.122).

Survival and mortality analysis

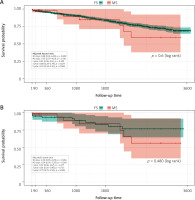

Analysis of key endpoints revealed no statistically significant difference in survival between the MS and FS groups (log rank = 0.6, stratified logrank after PSM = 0.48). The primary endpoint analysis, a multivariable clustered Cox regression on the matched cohort, reinforced these findings (Table V). Early mortality was minimal across the study, with only a single event noted in the unmatched cohort and zero events in either group after propensity score matching. This lack of a significant difference persisted at the 30-day follow-up, both in the initial unmatched cohort (1.6% for MS vs. 2.0% for FS; aHR = 0.88; p = 0.899) and in the propensity score-matched cohort, with non-significantly lower mortality in MS (1.7% vs. 4.9%; aHR = 0.34; p = 0.266) (Table VI).

Table V

Complications before and after PS matching

Table VI

Mortality before and after PS matching

Similarly, for late mortality at 1 year, the difference between the groups was not statistically significant, both before matching (1.6% vs. 4.2%; aHR = 0.43; p = 0.399) and after (1.7% vs. 6.7%; aHR = 0.32; p = 0.177). This lack of a significant difference in survival between the two groups persisted throughout the entire long-term follow-up period, including at 3 and 5 years after the procedure. The 5-year survival was not significantly different in both groups: before PSM (aHR = 0.92; 95% CI [0.34–2.5]; p = 0.868) (Figure 1 A) vs. after PSM (aHR = 0.79, 95% CI [0.25–-2.5]; p = 0.688) (Figure 1 B).

The final model demonstrated good discriminative ability (concordance index = 0.710) and identified a higher EuroSCORE II as the main independent predictor of mortality (HR = 1.22, 95% CI: 1.03–1.45; p = 0.024) (Figure 2 B).

Adverse events in the propensity score-matched cohort

In this matched cohort, CPB time remained significantly longer for the MS group (median: 73 vs. 63 min; p = 0.034), while the difference in aortic cross-clamp time was still not statistically significant (median: 56 vs. 51 min; p = 0.094). Postoperatively, the rates of new-onset AF, renal failure, and pacemaker implantation remained similar between the groups, without significant differences. However, the MS procedure was associated with a significantly higher requirement for norepinephrine support (90.8% vs. 61.5%; p < 0.001) and a longer cardiopulmonary bypass time (median: 73 vs. 63 days; p = 0.034) (Table IV).

Discussion

The comparison between MS and FS has been extensively studied, with our research adding valuable insights. We conducted a retrospective study including 1,289 patients, with 73 undergoing MS and 1,216 undergoing FS. Before propensity score matching, significant differences were observed in several clinical outcomes. Prothesis size was larger in MS, 23 [23–25] vs. 23 [21–25] in FS, and this finding corresponds with Kapadia et al., suggesting that in MS sutureless vales are more frequently implanted, translating into a larger size of the prosthetic valves [12]. Cardiopulmonary bypass time was longer in the MS group (71 min) compared to the FS group (63 min), and this finding contrasts with Borger et al., who emphasize the efficiency of MS techniques. The length of stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) was shorter for MS patients (2 days) compared to FS patients (3 days), a benefit supported by Semsroth et al. (2015), who demonstrated that MS leads to reduced ICU stays, which can be also a cost-effectiveness benefit [7, 13]. Interestingly, inotropic demand was higher in the group with a minimally invasive technique, but it was also reported by Szwerc et al. [14]. All these differences after propensity score matching vanished despite longer CPB time and higher norepinephrine demand in the MS group. The longer CPB time in the MS group is consistent with other reports, including those by Khalid et al., who also noted increased CPB times in minimally invasive procedures [5, 15, 16]. This is related to the limitations of the method, as the minimally invasive access requires sequential execution of tasks in surgery, thereby extending the CPB time. The demand for norepinephrine in patients with MS was still higher, likely due to prolonged CPB times causing vasoplegia, resulting in higher doses of norepinephrine [14, 16]. Despite these differences, the overall complication rates were similar, echoing the results of Almeida et al. and Borger et al., who found no significant increase in adverse events with minimally invasive techniques [17, 18]. Moreover, this study supports, with borderline significance, reduced postoperative bleeding after surgery, which was in FS 600 ml (450–800) vs. 460 ml (335–610); p = 0.052 [19, 20]. Interestingly, higher incidence of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in the MS preoperatively (5.5% vs. 0%; p < 0.001) could be attributed to higher cardiovascular risk profiles of patients, compared to those undergoing traditional surgery [21]. Additionally, the stress and physiological changes associated with the preoperative period might exacerbate underlying coronary conditions, leading to a higher incidence of ACS especially when aortic stenosis is present [22]. Moreover, our MS patients had higher perioperative risk (EuroSCORE II) after PSM (HR = 1.22 (1.03–1.45); p = 0.024) (Figure 2 B).

We also evaluated the 5-year outcomes of patients undergoing MS for AVR compared to those undergoing FS. Our results showed no significant difference in 5-year survival rates between the MS and FS groups, both before and after PSM: before (aHR = 0.92; 95% CI [0.34–2.5]; p = 0.868) vs. after (aHR = 0.79, 95% CI [0.25–2.5]; p = 0.688). These results are consistent with the findings of Semsroth et al. and Gasparovic et al., who reported comparable survival rates between minimally invasive and conventional approaches [7, 10]. Similarly, Phan et al. conducted a meta-analysis that supported the equivalence in survival outcomes between the two surgical techniques [9, 23]. We also contribute with this study to the ongoing debate about the mid-term efficacy of MS [23, 24]. While immediate postoperative benefits are well documented, as highlighted by Thourani et al. and Johnston et al., the long-term outcomes remain a critical area of research [2, 25].

Several limitations of this study merit acknowledgment. The primary limitation is its retrospective, non-randomized design. Although we employed propensity score matching to balance baseline characteristics, the potential for bias from unmeasured or unknown confounding variables can never be fully excluded. A second major challenge was the presence of missing data. We made a deliberate decision to forgo multiple imputation due to a strong suspicion of a missing-not-at-random (MNAR) mechanism, where the reasons for missingness could be linked to patient outcomes. Furthermore, the complexity of imputing heterogeneous data types, including multicategorical variables, and the risk of misrepresenting potentially complex, non-linear clinical relationships led us to adopt a more conservative approach. Consequently, our core analyses relied on a complete-case methodology. Specifically, both the propensity score matching model and the primary Cox proportional hazards model were constructed using only patients with complete records for all variables included in those respective models. While this approach ensures that the models themselves are built on robust, complete data, it necessitated the exclusion of patients with any missing baseline information, which reduces statistical power and may limit the generalizability of our findings. Descriptive data for variables presented in tables but not included in the core PSM or survival models should be interpreted with caution, as they are subject to their own distinct patterns of missingness.