Introduction

Intrahepatic cholestasis (ICH) is the most common liver disease of pregnancy. Its prevalence varies according to ethnicity, geographical regions, and environmental factors [1]. Data in the literature show that it varies between 0.3% and 15% in different populations [2]. ICH is characterized by pruritus, especially on the palms and soles of the feet, and high serum bile acid levels without specific skin lesions. ICH is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes, including premature delivery, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, fetal asphyxia, and even stillbirth [3].

The pathogenesis of ICH is still not fully known today. It is thought that increased bile acids in the mother pass to the fetus through the placenta and accumulate in the amniotic fluid or myocardium and cause fetal complications. Increased fasting serum bile acids with itching of the hands and feet, especially at night, are diagnostic. However, measuring serum bile acid levels is an expensive and not easily accessible laboratory test. ICH usually causes clinical signs and symptoms after the second trimester. Therefore, prediction of ICH in the early gestational weeks may help clinicians carry out close follow-up and reduce adverse fetal outcomes by early diagnosis [4].

The aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to platelet (PLT) ratio index (APRI) is considered an indicator of liver fibrosis that can be easily calculated using routine laboratory blood tests [5]. The APRI score has previously been extensively studied to detect liver damage in patients with hepatitis C [6]. It has also been studied in obstetrics, particularly in ICH and HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet) syndrome [7, 8]. In summary, the APRI score is considered to be an inexpensive, non-invasive, and easily accessible test that can be used to predict liver injury. A review of the literature has shown that first-trimester APRI scores are useful in predicting cholestasis [4, 7].

In this study, we aimed to compare the first, second and third trimester APRI scores in pregnant women with and without ICH. Moreover, the utility of the APRI score was analyzed to understand its usefulness in clinical practice.

Material and methods

This study was designed as a retrospective case-control study. The data of pregnant women admitted to the obstetrics and gynecology department in our clinic between January 1, 2018, and March 31, 2024 were collected. Patient information was obtained from file archives together with a computerized electronic hospital system. The study was planned in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approval was obtained from the Selcuk University Faculty of Medicine Local Ethics Committee (Ethics Committee number: 2024/87) before starting the study.

Patients with pruritus together with fasting serum bile acid level > 10 μmol/l were diagnosed with ICH after exclusion of other hepatobiliary causes. Patients with known hepatobiliary diseases and maternal diseases, as well as those who did not meet the diagnostic criteria for ICH, were excluded from the study. The control group consisted of pregnant women with similar clinical characteristics and without any maternal diseases or fetal abnormalities. Exclusion criteria were multiple pregnancies, chromosomal or structural fetal anomalies, obstetric complications (placenta previa, hypertensive diseases of pregnancy, diabetes mellitus), and maternal comorbid diseases.

Maternal age, gravida, parity, body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters), AST values, PLT count, gestational age at delivery, pregnancy complications, mode of delivery, obstetric and perinatal outcomes were obtained for each patient. For patients diagnosed with cholestasis, data on bile acid levels and gestational week at diagnosis were also obtained.

In the study, laboratory test results for the period 8 to 14 weeks for the first trimester, 20 to 24 weeks for the second trimester, and 28 to 32 weeks for the third trimester were used to standardize laboratory findings. APRI scores were calculated using complete blood count and liver function tests. APRI score was calculated as AST/PLT ratio as described previously [5]. Demographic characteristics, neonatal outcomes, and laboratory findings were compared between the two groups.

Statistical analysis

The analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22. Descriptive data were presented as n, % values for categorical data, and median with interquartile range (25th-75th percentile values) for continuous data. Chi-square analysis (Pearson χ2) was used to compare categorical variables between groups. Compliance of continuous variables with normal distribution was evaluated by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to compare paired groups. The IPC diagnostic value of the APRI value was measured by ROC analysis. The Youden index was used to calculate the most appropriate cut-off value. The statistical significance level was accepted as p < 0.05 in the analyses.

Results

A total of 113 patients (54 in the case group and 59 in the control group) were included in the study. Demographic data, obstetric characteristics, and neonatal and delivery outcomes of the patients are presented in Table 1. Gestational age at delivery was 37.00 (36.00-37.00) weeks in the cholestasis group and 38.00 (38.00-39.00) weeks in the control group (p ≤ 0.001). Birth weight was 2910.00 g (2500.00-3100.00) in the cholestasis group and 3340.00 g (2980.00-3640.00) in the control group (p ≤ 0.001). The rate of preterm delivery was 27.8% and 1.7% in the study and control group, respectively (p ≤ 0.001) The rate of intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) was higher in the cholestasis group than in healthy pregnant women (13.0% vs. 1.7%, p = 0.027).

Table 1

Comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics of case and control groups

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | ICH group (n = 54) | Control group (n = 59) | p* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |||

| Age | 29.00 (25.00-35.00) | 28.00 (24.00-33.00) | 0.188 | |

| Gravidity | 2.00 (1.00-3.00) | 2.00 (2.00-3.00) | 0.661 | |

| Parity | 1.00 (0.00-1.00) | 1.00 (0.00-2.00) | 0.114 | |

| BMI | 29.07 (27.53-32.87) | 29.69 (27.06-31.64) | 0.879 | |

| Bile acid value | 25.50 (17.00-42.00) | – | – | |

| Gestational age at ICH diagnosis | 32.50 (30.00-34.00) | – | – | |

| Gestational week at birth | 37.00 (36.00-37.00) | 38.00 (38.00-39.00) | < 0.001 | |

| Birth weight | 2910.00 (2500.00-3100.00) | 3340.00 (2980.00-3640.00) | < 0.001 | |

| APGAR score (1st minute) | 7.00 (6.00-8.00) | 7.00 (7.00-8.00) | 0.381 | |

| APGAR score (5th minute) | 9.00 (8.00-9.00) | 9.00 (8.00-9.00) | 0.152 | |

| Mode of delivery, n (%) | NVD | 22 (40.7) | 26 (44.1) | 0.721** |

| CS | 32 (59.3) | 33 (55.9) | ||

| Preterm labor ratio, n (%) | 15 (27.8) | 1 (1.7) | < 0.001** | |

| IUGR ratio, n (%), Yes | 7 (13.0) | 1 (1.7) | 0.027** | |

| Meconium amnion, n (%), Yes | 2 (3.7) | 0 (.0) | 0.226** | |

The findings of the laboratory results of the case and control groups are shown in Table 2. AST was similar in the case and control groups in the first trimester, whereas it was significantly higher in the case group in the second and third trimesters (p = 0.140, p ≤ 0.001, p ≤ 0.001, respectively). PLT was similar in case and control groups in all three trimesters (p = 0.271, p ≤ 0.275, p ≤ 0.947, respectively). APRI scores were significantly higher in the case group in all three trimesters (p = 0.028, p ≤ 0.001, p ≤ 0.001, respectively).

Table 2

Comparison of APRI scores of case and control groups

| Parameter | ICH group Median (IQR) | Control group Median (IQR) | p* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st trimester AST (U/l) | 15.00 (12.00-19.00) | 14.00 (12.00-15.00) | 0.140 |

| 1st trimester PLT (K/μl) | 240.00 (210.00-290.00) | 267.00 (218.00-316.00) | 0.271 |

| 2nd trimester AST (U/l) | 24.00 (18.00-38.00) | 14.00 (12.00-17.00) | < 0.001 |

| 2nd trimester PLT (K/μl) | 223.50 (195.00-268.00) | 239.00 (205.00-284.00) | 0.275 |

| 3rd trimester AST (U/l) | 52.00 (33.00-85.00) | 16.00 (13.00-18.00) | < 0.001 |

| 3rd trimester PLT (K/μl) | 214.00 (180.00-280.00) | 225.00 (186.00-271.00) | 0.947 |

| First-trimester APRI score | 0.06 (0.05-0.08) | 0.05 (0.04-0.06) | 0.028 |

| Second-trimester APRI score | 0.12 (0.08-0.18) | 0.06 (0.05-0.08) | < 0.001 |

| Third-trimester APRI score | 0.25 (0.14-0.45) | 0.07 (0.05-0.09) | < 0.001 |

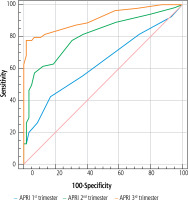

The utility of APRI scores to predict ICH was investigated by ROC analysis, and cut-off values were determined. We found that using a cut-off value of 0.06 for the first trimester APRI score, the sensitivity was 42.6% and the specificity was 83.1%; using a cut-off value of 0.1 for the second trimester APRI score, the sensitivity was 57.4% and the specificity was 93.2%; and using a cut-off value of 13 for the third trimester APRI score, the sensitivity was 77.8% and the specificity was 98.3% (Table 3, Fig. 1).

Table 3

Specificity and sensitivity of APRI values in determining severity of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the efficacy of using the APRI score, a non-invasive and convenient method for predicting ICH. AST levels in the second and third trimesters were found to be significantly higher in ICH patients compared to control patients. APRI scores were significantly higher in all three trimesters.

In a previous study, adverse perinatal outcomes, including preterm delivery and low birth weight, were found to be statistically significantly more frequent in the ICH group compared to the control group. Many studies in the literature have reported that ICH is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes [9, 10]. Cui et al. performed a meta-analysis using data from women with ICH and found that adverse perinatal outcomes (e.g., preterm delivery) were more frequent in women with bile acids above 40 μmol/l. This study found no effect on the risk of stillbirth compared to women with low bile acids [11]. Another meta-analysis reported that perinatal mortality was increased in patients with bile acids higher than 100 μmol/l. However, the exact reason for this could not be determined because there were very few patient groups with bile acids higher than 100 μmol/l. It was emphasized that the causes of stillbirth should be investigated in the future with large case series. In the same study, serial bile acid monitoring was recommended to reduce stillbirths, and it was argued that the mode of pregnancy management should be determined according to the highest bile acid level [12].

It has been known for years that ICH is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes. Therefore, the diagnosis and management of this patient population are of great importance. The gestational age at delivery of these patients is still controversial. In one study, the prevalence of stillbirth for all bile acid groups was less than 1% before 35 weeks gestation. In the same study, it was found that there was no increase in stillbirth before 39 weeks gestation in singleton pregnancies with bile acid concentrations below 100 μmol/l; however, the prevalence of preterm delivery of 25.3% may have prevented late stillbirths [12]. In a meta-analysis, Lo et al. compared delivery at 36 weeks gestation with delivery at 35 weeks gestation to reduce perinatal death from ICH. They argued that the 36th week of gestation was the most appropriate delivery week, with life years adjusted for maternal and neonatal quality of life [13]. In our study, despite unfavorable perinatal outcomes, there was no perinatal death. We believe that this was due to the early identification of patients, early initiation of treatment, and planning of delivery at 37 weeks gestation.

Although the utility of APRI in predicting the development of ICH has been investigated in several studies, our knowledge is still limited due to the heterogeneous design of the studies and the relatively small number of cases [14].

Adverse perinatal outcomes due to intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) have been demonstrated in many studies. Chen et al. found an increased risk of preterm delivery and low birth weight, as well as a high rate of cesarean section in patients with ICP [15]. A meta-analysis clarified the adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with ICH and found that women with serum bile acids of 100 μmol/l or more had a significantly increased risk of stillbirth [12]. Brouwers et al. found that spontaneous preterm delivery, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, and perinatal death were significantly more common in patients with severe ICH. The risk of stillbirth was found to be significantly higher in women with meconium-stained amniotic fluid than in controls [16]. Our findings are consistent with the literature. Fetal growth restriction and preterm delivery were statistically significantly higher in the ICH group, while gestational age at delivery and birth weight were significantly lower in the ICH group compared to the control group.

Early recognition and management of ICH may help in reducing maternal and fetal complications. Several protocols have been proposed for the management of ICH. While early studies focused on risk factors, more recent studies have emphasized the diagnosis and management of the disease. The use of biochemical markers such as APRI and NLP (neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio) as screening tests to predict ICH has been attempted. According to the results of a previous study, the APRI score calculated in the first trimester of pregnancy can be used as a predictor of ICH development in the third trimester [7]. APRI has also been studied to predict the development of HELLP syndrome and other liver diseases, such as hepatic fibrosis. According to the results obtained, the first-trimester APRI score (0.64 ±0.10) of women who developed HELLP syndrome in the third trimester of pregnancy was found to be significantly higher than the control group (0.40 ±0.12) (p < 0.001). In ROC analysis, the sensitivity and specificity of a cut-off value of 0.55 for the first trimester APRI score in predicting the development of HELLP syndrome in the third trimester were calculated to be 88.1% and 94.6%, respectively [17].

The livers of pregnant women undergo physiological and pathological changes, and changes in liver enzyme activity and secretion reflect changes in serum enzymatic activity. Therefore, there are many studies evaluating the activities of alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) isoenzymes and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) in the serum of women with ICP. According to the analysis of these studies, ICP pregnancy is associated with statistically significantly elevated ADH I and total ADH activity. Additionally, total ADH activity has been found to be positively correlated with ALT, AST, and total bile acids [17-19].

In a study comparing ICH and control groups, Peker et al. found that APRI scores were significantly higher (p < 0.001) in the ICH group in all trimesters. The cut-off values of APRI scores for predicting ICH in the first, second, and third trimesters were 0.101 (79.7% sensitivity, 79.6% specificity), 0.103 (78.4% sensitivity, 76.3% specificity), and 0.098 (72.5% sensitivity, 72% specificity), respectively [4]. Tolunay et al. found that the first-trimester APRI scores of ICH patients were significantly higher (p < 0.001) compared to the control group. In ROC analysis, the cut-off value for the APRI score was determined to be 0.57, with 86.5% sensitivity and 77.3% specificity [7]. Similarly, in our study, the APRI score was found to be significantly higher in the ICH group compared to the control group in all trimesters (p = 0.028, p < 0.001, p < 0.001, respectively). The ROC analysis cut-off values for the APRI score to predict ICH were 42.6% sensitivity and 83.1% specificity when the cut-off value for the first-trimester APRI score was 0.06, and the cut-off value for the second-trimester APRI score was 0.06; when 1 was taken as the cut-off value, 57.4% sensitivity and 93.2% specificity were found; and when the cut-off value for the third-trimester APRI score was 13, 77.8% sensitivity and 98.3% specificity were found, and it was found to be a good predictor.

Although the results of our study provide important statistical data, it has limitations such as retrospective design, being single-center, and having a limited number of patients.

In conclusion, the APRI score was positively associated with ICH in our population. Bile acids are not always an easy laboratory result to use and access. Therefore, our findings can be used as a basis for future studies aimed at the prediction and prevention of ICH and related complications.