Introduction

Depressive disorders are a serious social and health problem, causing a significant impact on socio-occupational functioning of affected individuals at all ages, in different cultures and ethnic groups [1–3]. This often places a huge burden on affected people, their families, and, more broadly, the social and economic system of the country [4, 5]. Depression reduces work productivity and the sense of life satisfaction, and is a cause of reduced quality of life and disability [6].

The EZOP study, (Epidemiology of Psychiatric Disorders and Accessibility of Psychiatric Health Care EZOP-Poland) [3] confirmed the pervasive problem of depression in Polish society. Depressive disorders and neurotic disorders were diagnosed in 13.1% of respondents, affecting about 5 million people in Poland. Approximately 3% of the Polish population have experienced at least one depressive episode during their life. In comparison with other European Union countries, Poland is in 9th from last place on the ranking list for the rate of suicides, undoubtedly related to depressive disorders. This indicator has remains unchanged for several years, ranging from 13–14 per 100 000 inhabitants [7].

The gap between the prevalence of mental disorders (based on the study EZOP) and the number of patients treated in mental health clinics (Central Statistical Office, Health and Health Care in 2014) suggests that many patients with mental disorders (primarily depressive disorders and anxiety) are not seen by a specialist psychiatrist at all. However, they often visit other doctors, non psychiatrists (i.e. internists, GPs, neurologists), usually complaining about various somatic problems, the main source of which is unrecognized depression [8]. The prevalence of depression in the primary care population is as high as 23% [9]. It is estimated that only half of these patients have a properly established diagnosis and are given antidepressant treatment [10]. Meanwhile, available studies confirm the importance of early diagnosis of depression and quick implementation of appropriate therapy. A shorter period of untreated depression translates directly into higher response rates, remissions, and lower disability rates, and reduces the risk of mortality and health complications [11, 12].

Depression, especially when untreated, increases the risk of somatic diseases, and vice versa – somatic diseases, especially chronic ones, increase the risk of depression [13, 14]. According to the World Health Organization Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020 [2], people with mental disorders experience a disproportionately greater number of disabilities and illnesses in their lives. About 31% of adults with diabetes have clinically significant symptoms of depression [15]. The relationship between depression and hypertension is also bilateral – higher rates of hypertension in people with depression were observed in the study of Wang et al. [16]. Moreover, effective antidepressant treatment led to blood pressure normalization [17]. Similarly, the relationship between depression and ischaemic heart disease and the risk of sudden cardiac death has been undisputedly confirmed in many studies [18–22]. Depression is also very often associated with cancer [23], reducing the patient’s willingness to be treated, affecting the immune system, and worsening the prognosis in cancer. As many as 20 years after a cancer diagnosis, the risk of depression decreases to a comparable level as in the general population [23].

A particular problem is the occurrence of depressive episodes in the postnatal period. The prevalence of depressive disorders in women in the postnatal period is estimated to be around 15–20% [24, 25], which makes it the most common postnatal complication [26].

Patients with depression often, due to different reasons (for example fear of stigmatization, lack of knowledge about the condition, lack of insight, difficulties in access to a specialist doctor), do not go to a psychiatrist at all. With limited availability of specialist psychiatric care, the most appropriate measures seem to be those aimed at increasing the competence of doctors of other specialties, especially GPs and internists (appropriate screening tool, specific guidelines for diagnosing and treating depression) in the diagnosis and treatment of depression.

Material and methods

An overview of the worldwide literature, as well as available recommendations for prevention, screening, and treatment of patients with depression was performed. The search was conducted from inception of the database to November 2020 using the keywords “depression” OR “depressive disorder” OR “major depression” AND “guideline” OR “recommendation”. The following electronic bibliographic databases were searched: MEDLINE/PubMed, EmBASE, PsycINFO, and Cochrane library. Forward and backward citation searches of included articles was also performed to further locate papers that were not identified in the database search. Additionally, we searched the following websites of agencies and scientific associations related to mental health or preventive medicine: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org), World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (http://www.wfsbp.org), Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health (https://comp-ocpm.ca/english/community-partnerships/canadian-agency-for-drugs-technologies-in-health-cadth.html), European Psychiatrist Association (http://www.europsy.net/publications/guidance-papers), American Psychiatric Association (https://www.psychiatry.org), Royal College of Psychiatrists (https://www.racgp.org.au), National Institute of Mental Health (https://www.nimh.nih.gov), American College of Preventive Medicine (https://www.acpm.org), Michigan Quality Improvement Consortium (http://www.mqic.org), Institute of Clinical Systems Improvement (https://www.icsi.org), American Family Physician (https://www.aafp.org), Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (https://www.racgp.org.au), Beyondblue (https://www.beyondblue.org.au), Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (https://canadiantaskforce.ca), Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (https://www.canmat.org), Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense (https://www.va.gov/vadodhealth), National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (https://www.nice.org.uk), American Geriatrics Society(https://www.americangeriatrics.org), Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (https://www.sign.ac.uk), and New Zealand Guidelines Group (https://www.guidelinecentral.com/summaries/organizations/new-zealand-guidelines-group). Guidelines that concern screening, diagnosis, and management of depression in settings other than mental health services, in English language, regularly updated, most recently over the last 5 years were considered. Further evaluation was performed in accordance with the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluations (AGREE II instrument) [27]. The final recommendations for Polish physicians were compiled based on the selected guidelines (Table 1).

Table 1

Guidelines for screening and treatment of depression

| Organization | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| US Preventive Services Task Force [27] | Recommends a routine screening of the adult population. At the same time, it indicates the need to provide coordinated treatment. |

| American College of Preventive Medicine [28] | It recommends routine screening for depression in the adult population. Stresses the need for coordinated patient care. |

| Michigan Quality Improvement Consortium Guideline [29] | Recommends a routine screening for depression in the adult population using PHQ-2 and/or PHQ-9. In people with risk factors, the screening should be performed at each visit. |

| Institute of Clinical Systems Improvement [31] | Recommends routine screening for depression in the adult population using PHQ-2 and/or PHQ-9. |

| American Family Physician [30] | Recommends routine screening of the adult population and children and adolescents (12–18 years old) using the PHQ-2 and/or PHQ-9 or Geriatric Depression Scale-15 questionnaires in the elderly population. |

| Royal Australian College of General Practitioners [41] | It recommends routine screening of the adult population and children and adolescents (12–18 years old) using PHQ-2 and/or PHQ-9. In people with risk factors the screening should be performed at each visit. |

| Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care [50] | It does not recommend routine screening for depression in the general population or in patients at risk. |

| National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence [25, 26] | It recommends that patients in the high-risk group, especially patients with chronic somatic disease, be carefully monitored and screened using a set of 2 questions. Furthermore, it recommends a graded approach to treatment. |

| Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense [61] | It recommends routine screening for depression using PHQ-2 in patients that are not currently treated for depression, and PHQ-9 in patients with diagnosed depression to monitor the treatment. Stresses the need for coordinated patient care. The first-choice treatment for an uncomplicated episode of mild to moderate depression should be pharmacotherapy and/or psychotherapy. Patients who have not responded to treatment with antidepressants used in the therapeutic dose after 4–6 weeks should be referred to a psychiatrist for further treatment. The treatment should be continued for at least 6 months. |

| Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments [60] | Stresses the need for coordinated patient care. It specifies in detail the drugs used as first- and second-line treatment for depression. |

Results

The results of the literature and recommendations review in terms of the prevention of and screening for depression

According to the available data, recommendations for the prevention, screening, and treatment of depression have been developed in many countries around the world. The recent review of guidelines for the management of depression identified all national (n = 82) and international (n = 13) clinical practice guidelines from around the world [28]. All these recommendations were developed in the 21st century and are updated periodically. In this study we have focused on the most comprehensive guidelines targeting depression in adults in settings other than mental health services.

The most comprehensive recommendations, covering many issues related to depression, are depicted in the guidelines of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [29, 30] and in documents developed by American organizations and associations (US Preventive Services Task Force – USPSTF, American College of Preventive Medicine – ACPM, Michigan Quality Improvement Consortium Guideline – MQICG, American Family Physician – AFP, Institute of Clinical Systems Improvement – ICSI) [31, 35].

Many experiences in the prevention of depression also come from Australia. One of the best-known programmes is the Australian-led Beyondblue programme [36] (www.beyondblue.org.au), which was established in 2000 as a 5-year national initiative to raise public awareness of early responses to depressive behaviour. Retrospective research conducted in subsequent years confirmed the effectiveness of this program in terms of increased public awareness and improved treatment of depression in Australia [37, 38].

Interesting experiences in this matter also come from European countries. A 2-year program to combat depression conducted in Nuremberg [39] allowed for a significant reduction in the number of suicides (by about 20%) and improved early detection and care for patients with depression. The concept of this program is based on different levels of impact: cooperation and training for GPs, social campaigns to raise awareness and basic knowledge about depression, training for key professions (i.e. teachers, priests, police, carers of elderly people), and the creation of support groups and specific facilities for access to professional care for patients with a higher risk of suicide. This program, with various modifications, has been implemented in many other countries. Evaluation of its effectiveness in subsequent years confirmed a significant decrease in the number of suicides and improved early detection of depression.

Country-specific recommendations for depression screening either in routine screening in the general population, which is widely recommended by American organizations [31, 35], or screening in selected risk groups, as applied in the UK (NICE, 2009, 2018) [29, 30]. The USPSTF recommends routine screening of adult populations [31]. The ACPM [32] supports this guideline, recommending its implementation in primary care settings and the development of patient care models based on collaboration with psychiatrist consultants [40]. O’Connor et al. [41] and Pignone et al. [42] also point out that screening is more effective if a system of follow-up care is properly organized. Belnap et al. [43] and Gilbody et al. [44] note that comprehensive care for depressed patients based on cooperation between different professionals is more effective than the traditional approach. The MQICG (2016) [33] also recommends routine screening of the adult population but does not specify how often such screening should take place. However, patients at higher risk of depression, as well as patients who are suspected of depressive symptoms, should be screened at every opportunity. The above guidelines recommend the use of the Patient Health Questionnaire version 2 (PHQ-2) and/or the Patient Health Questionnaire version 9 (PHQ-9) for screening. Similarly, the ICSI [35] recommending routine screening of the general population with PHQ-2 and/or PHQ-9. In the case of positive screening, further testing is recommended. The ICSI recommends referral to psychiatric care in the following situations: if the patient declares suicidal thoughts, has no response to the treatment, or has other psychiatric conditions. The doctor should also educate each patient about depression and assess the level of support in their immediate surroundings. Also, the AFP [34] (www.aafp.org), like other American organizations, recommends a routine survey of the adult and youth population (12–18 years old). It recommends the use of the most practical screening tool for a given doctor. Most often it is a PHQ-2. If the patient answers positively to any of the 2 questions, further testing with PHQ-9 is recommended.

In Australia, the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) [45] also recommends screening for depression in the adult population if there is a suitable structure for further treatment and coordinated patient care. In the case of a patient with risk factors, it recommends always considering the possibility of depression and performing screening in this population.

Some studies indicate the need for additional laboratory tests, e.g. assessment of TSH levels in blood in patients with symptoms of hypothyroidism [46]. The American Geriatrics Society [47] has also issued recommendations for additional tests, recommending the following tests in people with suspected depression: TSH, vitamin B12, calcium, electrolytes, parameters for kidney and liver function, morphology, and urine testing.

Concerning screening in risk groups, such an approach is recommended in the UK. Comprehensive recommendations for the detection and treatment of depression in adults and in people with chronic somatic diseases were published in 2 NICE documents (“The treatment and management of depression in adults” and “Depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem: recognition and management”).

According to the NICE document (Depression with a chronic physical health problem; NICE Clinical Guideline, 2009) [30] depression is 2–3 times more common in patients with chronic somatic diseases. Therefore, NICE and the vast majority of other guidelines recommend routine screening in the population of people with chronic somatic disease. Depression in this group of patients is often more difficult to diagnose because the symptoms of the disorders can be very similar. According to the American Psychiatric Association (APA) [48], many depressed patients do not complain at all about decreased mood or anhedonia, but instead complain about a variety of non-specific somatic problems or fatigue and are more likely to visit internists or GPs [49]. At the same time, depression worsens the prognosis in some chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases or diabetes [50, 51]. Therefore, early identification of depression through screening is particularly advisable.

Depression risk factors include the following [29, 30, 52, 55]:

past episodes of depression,

family history of depression,

other mental illness, addictions,

cancers,

Parkinson’s disease,

cardiovascular diseases,

diabetes mellitus,

neck pain, chronic pain,

other chronic somatic diseases,

unemployment, difficult life situation,

older people experiencing various life difficulties (chronic illness, mourning, institutional care).

NICE [29, 30] recommends that patients in the high-risk group are closely monitored and screened using a set of 2 questions:

Have you had feelings of sadness, depression, or hopelessness in the last month?

In the last month, did you experience reduced interest or reduced pleasure?

In the case of obtaining a positive answer to any of the questions, it is advisable to make a further assessment of the patient’s mental condition or refer them to a psychiatrist. For patients with chronic somatic illness, NICE recommends asking further questions:

Have you felt worthless during the last month?

Have you had problems with concentrating?

Have you had suicidal thoughts?

If the patient answers positively to any question, it is advisable to carry out further evaluation of the mental state or refer them to a specialist psychiatrist. It should also be considered whether the depression is not caused by drugs used in a somatic illness or otherwise related to the patient’s somatic condition.

Two questionnaires are most often mentioned in all of the above recommendations: PHQ-2 and PHQ-9. PHQ-2 is recommended for screening the population of all people over 12 years old. It consists of 2 questions. A result of 3 or more (out of 6 possible) means an indication for further evaluation, usually using PHQ-9. PHQ-9 consists of 9 questions that help to diagnose depression and assess its severity. It takes about 3 minutes to complete the questionnaire. PHQ-9 is recommended both as an initial assessment tool and as another supplementary questionnaire after PHQ-2, and it is particularly useful in monitoring symptoms when treating depression [56, 57]. A score of 6 or above for PHQ-9 requires further examination for depression [58]. Detailed guidelines of how to use PHQ-9 can be found at http://www.phqscreeners.com/instruc.Skala. The sensitivity of this questionnaire was assessed at 61% and its specificity at 94% [56]. A recent systematic review revealed that a 2-stage screening, in which a clinical interview confirmed or refused the preliminary PHQ-9 assessment, is the most recommended system [59].

Suicide risk assessment

The majority of recommendations refer to the potentially most serious depression-related situation – to an assessment of the risk of suicide, recommending an evaluation of the severity of such thoughts and an assessment of the patient’s ability to implement them. It is also stressed that the patient should be asked about their immediate environment and the support they can get there. For example, MQICG [33] recommends asking patients directly about their suicidal thoughts and plans, as well as about their family history of suicide. If such thoughts are declared, the risk of their implementation should be assessed and the patient should be referred for further psychiatric treatment (outpatient or inpatient treatment) as appropriate.

NICE [29, 30] recommends that patients with chronic somatic disease and depression are routinely asked about suicidal thoughts. If there is a positive history, it is recommended that the level of support in patient’s environment is assessed, all the medication that are taken are considered and the amount of these medications reduced if possible, intensifying contact with the patient is considered, including by telephone, and further assistance to apply to the threat is provided. However, the recommendations do not recommend routine population screening for suicide risk. The USPSTF states that there is insufficient evidence for screening the general population (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for suicide risk. May 2004) [60].

The results of the literature and recommendations review in terms of the treatment of depression

In patients with dysthymia and mild depression who do not require any formal intervention, an education, a visit plan (next visit in 2 weeks), and psychosocial interventions are recommended.

The first-choice treatment for an uncomplicated episode of mild to moderate depression is pharmacotherapy and/or psychotherapy [29, 61, 62]. The choice of treatment (pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy) is often dictated by the patient’s preferences and access to a psychotherapist [63]. Among the available psychotherapeutic methods for treating depression, cognitive-behavioural psychotherapy is preferred. However, it should be taken into account when choosing the treatment method that access to psychotherapy under public health care conditions is still limited in Poland, especially outside large urban areas [64].

In moderate to severe depression, the treatment of choice is pharmacotherapy with antidepressants [29, 64, 65]. Patients who have not responded to treatment with antidepressants used in a therapeutic dose after 4–6 weeks should be referred to a psychiatrist for further treatment [29, 64, 67].

Patients with severe depression, moderate depression, and other coexisting health problems that impact normal daily functioning should receive comprehensive, coordinated care [30]. The NICE guidelines recommend a graded approach to treatment:

Step 1 – suspicion of depression: examination and assessment of symptoms, support, psycho-education, intensive monitoring, possibly referral to further specialist care

Step 2 – confirmed mild/moderate depression: psychosocial interventions, psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, possibly referral to further specialist care

Step 3 – severe depression or lack of response to treatment in previous steps: pharmacotherapy, intensive psychotherapeutic interventions, combined treatment, referral to further specialist care

Step 4 – severe depression or other concomitant disorders, life threatening: pharmacotherapy, intensive psychotherapeutic interventions, combined treatment, referral to further specialist care, electroconvulsive therapy, hospital treatment

Basic principles of pharmacological treatment of depression

Basic knowledge of the diagnostics and treatment of depression by non-psychiatrists seems indispensable. It allows for the implementation of therapy in patients who would probably never go to a psychiatrist, as well as for a prompt referral to a psychiatric emergency unit (i.e. psychotic depression, auto-aggressive and aggressive behaviour, restriction of meals and liquids, presence of suicidal thoughts) [67–69]. With mild or moderate intensity of symptoms, prompt implementation of treatment by internists or GPs saves time, shortens the patient’s period of suffering, and prevents further aggravation of symptoms [64, 65].

The main aim of depression treatment is to achieve the fastest and fullest therapeutic response as well as symptomatic remission and return to pre-disease functioning. The basic principle of the treatment is to select drugs that act comprehensively, on the whole set of symptoms, and not only on its individual components (such as anxiety or sleep disorders) [65, 67, 68]. In the therapeutic process, cooperation with the patient, providing him/her with information about the diagnosis, course of the disease, methods of treatment, legitimacy of taking medicines, and ways of preventing and recognizing early symptoms of relapse is crucial [65]. The effect of the drug is usually visible after 2–4 weeks.

Choosing an antidepressant

A meta-analysis indicates that antidepressants, regardless of their mechanism of action, generate comparable percentages of treatment responses, ranging from 50% to 75%, significantly higher than placebo [63]. It is not only the efficacy that determines the choice of drug, but also the safety and tolerability. The choice of medication should also take into account the clinical features of depression in a given patient, coexisting diseases, and consequently other drugs taken by the patient and the risk of potential interactions.

The following should be taken into account in the selection of antidepressant for a given patient [65, 67, 68]:

clinical features of depression,

side effects profile,

coexisting somatic diseases and all drugs taken,

age of the patient and body weight (e.g. features of malnutrition, cachexia),

treatment used in previous depressive episodes (its effectiveness and tolerance),

co-morbidity with other mental disorders,

intensity of depressive symptoms (severe depression with psychotic symptoms, severe depression without psychotic symptoms, moderate depression, mild depression),

the patient’s compliance with the recommendations (e.g. in case of difficult cooperation with the patient, choosing a drug with the simplest possible dosing regimen, involvement in the treatment of the patient’s relatives, psychoeducation of the family),

doctor’s experience with the use of the medicine and the availability and price of the medicine.

Pharmacological treatment of episodes of postpartum depression in a woman who is not breastfeeding does not deviate from the recommendations for the treatment of depression not related to pregnancy and the postpartum period. The benefits of treatment for the mother should be considered when deciding on the inclusion of pharmacological treatment during breastfeeding, and the risks arising from the child’s potential exposure to the drug should be taken into account. The specificity of depression treatment during pregnancy and after childbirth in most cases requires treatment by a specialist psychiatrist (Table 2).

Table 2

An important factor in the selection of antidepressant treatment is also the patient’s somatic load. When choosing a drug, it is necessary to take into account possible side effects that may occur during the therapy. The following is a simplified proposal for the treatment of depression in selected somatic diseases (Table 3, Fig. 1).

Table 3

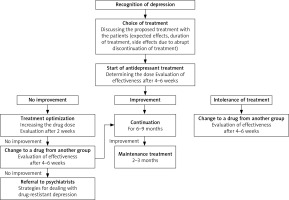

Treatment steps

Acute phase –active treatment (usually takes 6–8 weeks). This is the time from the beginning of the treatment to the remission of the symptoms. During this period, it is crucial not only to choose an antidepressant, but also to establish an adequate therapeutic dose (well tolerated by the patient and at the same time falling within the range of therapeutic doses). During this period, visits should be quite frequent to monitor the drug tolerance, occurrence of adverse reactions, and the occurrence of therapeutic response. It should be remembered that although signs of improvement may appear at the beginning of therapy, the reaction to treatment can only be assessed by using the drug in a therapeutic dose for at least 4–6 weeks.

Continuation of treatment with maintenance treatment – after obtaining symptomatic remission, treatment should be continued for at least half a year (according to some authors even 9–12 months) [66]. Doses of drugs during this time should be maintained or reduced to the minimum therapeutic dose. The length of treatment depends on the intensity of symptoms at the beginning of the therapy, the time of untreated depression, the time to therapeutic response, and any coexisting adverse environmental factors (personal/family/occupational/economic difficulties). If, during maintenance treatment, the patient experiences an increase in depressive symptoms, the dose of the drug should be increased or, if this treatment proves ineffective, the drug should be changed to another one with a different mechanism of action or the combined treatment should be started.

Preventing recurrence – the aim is to prevent relapse in the case of recurrent depressive disorders or bipolar affective disorder.

Withdrawal of drugs – when deciding to discontinue antidepressant treatment, it should be remembered that doses should be reduced slowly because of the risk of withdrawal symptoms. In the case of short-term antidepressant treatment the medication should be discontinued over a period of 1–2 weeks, in the case of treatment lasting 6–8 months the doses should be reduced over a period of 6–8 weeks, and in the case of long-term treatment the dose should be reduced by 25% every 4–6 weeks until complete discontinuation.

The most common mistakes concerning pharmacotherapy

The most common mistakes made by doctors [67, 68] are as follows:

underestimating suicide risk,

insufficient dose of antidepressants,

insufficient treatment time, rapid change from one antidepressant to another,

polytherapy,

underestimating adverse effects, treating somatic complaints as a sign of hypochondria, underestimating the role of drug interactions,

underestimating the role of therapeutic contact and proper doctor-patient cooperation,

overuse of benzodiazepines, use of benzodiazepines for too long (risk of addiction), or replacement of antidepressants with benzodiazepines,

insufficient education of the patient and his/her relatives about the disease and the rules of its treatment.

Common reasons for treatment ineffectiveness

The aim of antidepressant treatment is to relieve symptoms and restore functioning at pre-disease levels, and to prevent relapse. In some patients, however, despite repeated modifications of the pharmacological treatment, remission and sometimes even stable improvement is still not achieved. Sometimes the treatment causes side effects that are not accepted by the patient and are the reason for early discontinuation of treatment. Studies have shown that about 20–30% of properly treated patients do not respond to treatment. In some cases, this can be so-called “pseudo-resistance”. The lack of therapeutic effect is then a result of misdiagnosis, inadequate pharmacotherapy (inappropriate drug, inadequate dose, inadequate treatment time, failure to follow the recommendations), or interaction with other drugs.

Potential causes of treatment ineffectiveness [67, 68] are as follows:

inadequate duration of treatment,

misdiagnosis,

inadequate dosage,

inappropriate choice of medication,

non-compliance with doctor’s recommendations, lack of doctor-patient cooperation,

coexistence of other mental or somatic disorders,

individual characteristics of the patient’s metabolism (slow metaboliser/fast metaboliser),

coexistence of somatic disorders,

interactions with other drugs taken by the patient,

presence of organic changes in the central nervous system,

old age,

factors supporting symptoms of disease,

omitting psychotherapeutic assistance,

withdrawal from treatment too early,

associated addiction to psychoactive substances/alcohol.

Discussion

Diagnosis of the situation in Poland – barriers and possible solutions

As already mentioned, registered reporting to psychiatric health care facilities is very low and does not reflect the prevalence of depression. This marked discrepancy highlights the scale of the problem and the extent of unmet needs. This naturally raises the question concerning the reasons. It seems that the problem is complex and requires careful consideration on several levels. Some patients do not realize the problem at all and do not seek medical help, some go to a doctor or other specialist, some to a psychologist, and only a small part to a specialist psychiatrist. The availability of public psychiatric care is a problem faced by patients throughout the country. It goes without saying that for a depressed patient, waiting several months for help and treatment is a very long and suffering-filled time, during which his/her chances of full recovery are diminishing. Studies confirm that early diagnosis and treatment of depression translates directly into a higher rate of remission, and reduces the risk of relapse and mortality [11, 12]. Various actions are possible to improve this situation. These include, in particular, increasing the knowledge and competence of doctors – the medical personnel who most often come into contact with people with depression. Many studies emphasize the need to develop recommendations in individual countries, taking into account various cultural factors as well as the specificity of the healthcare system in a given country [70]. A recent review of guidelines for the management of depression summarized all worldwide clinical practice guidelines [28]. The authors of this review also stressed the importance of considering the strategies to implement recommendations in given countries. Obviously, in various settings health-care personnel might be constrained in their ability to provide timely and appropriate mental health interventions [71]. The conclusion that could be drawn from above review is the importance of the practical aspects of application of guidelines in given countries. In particular, the government policies that require adherence to recommendations could facilitate their implementation. A clear indication on screening tools and algorithms for the treatment and management of depression could also be helpful. This could make it easier for physicians to do the work that they are already doing.

The problem of availability of specialist psychiatric care and the organization of an effective system in this field is faced by many countries, including Poland. The solutions applied in other countries vary widely. However, the common denominator seems to be the shift of part of the burden of care to primary settings, internists, or neurologists. This applies in particular to the diagnosis of depression and the first-line treatment of typical, uncomplicated cases. So, it would make sense if the doctor the patient sees first were able to establish the proper diagnosis. These patients often complain about a variety of somatic problems, and the main source of these complaints is unrecognized depression. A study conducted in Poland indicated the prevalence of depression in the population of primary care patients reaching 23% [9].

Another important issue is the organization of the overall system to provide comprehensive, coordinated care for patients with depression. Such teams include internists, family doctors, psychiatric specialists, psychologists, therapists, and members of community care teams.

Leading organizations worldwide, such as the ACPM, recommend the implementation of collaborative care models with psychiatrist consultants [32]. In Poland, however, the separation of primary care from specialist psychiatric care is strongly expressed.

As well as system-organizational barriers, equally important and strongly rooted awareness barriers remain. The main problems seem to be lack of knowledge about depression in society and stigmatization. This has been confirmed by the results of the EZOP survey [3], which revealed very limited knowledge and experience with people with mental illness in Polish society. These views seem to be very deeply rooted and largely culturally independent, and many societies in the world are trying to rectify this problem.

Recommendations for prevention, screening, treatment, and management of depressed patients for physicians

The purpose of these guidelines is to define, for the use by physicians, the procedure of screening for depression in adults, as well as treatment and further management of patients with recognized depression.

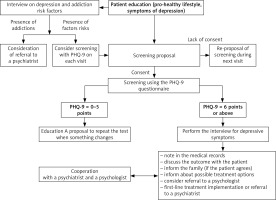

Recommendations for the prevention and screening for depression in adults

It is recommended that patients and their families are educated about possible early symptoms of depression and risk factors.

The presence of depressive symptoms should be routinely assessed during the first visit using the PHQ-9.

The presence of depressive symptoms should be routinely assessed at least once a year and in any situation indicating possible mental deterioration, as well as in patients with risk factors (in particular, patients with chronic somatic disease, chronic pain, and history of depression) at every possible opportunity using the PHQ-9.

It is recommended that the purpose of the screening be explained to the patient and their informed consent obtained to complete the questionnaire.

If the patient refuses to complete the PHQ-9, the screening should be offered again at the next visit.

It is advisable to perform an interview regarding depression risk factors. It is recommended that the following risk factors are asked about:

It is also advisable to ask about alcohol and drug addiction. In case of a positive history, it is recommended that referring the patient to psychiatric care be considered.

In the case of a score of more than 6 points in the PHQ-9, it is recommended that a further interview be conducted to confirm the diagnosis of depression or to refer to a psychiatrist. The interview should include questions about the occurrence of particular depressive symptoms according to ICD-10 criteria:

A positive result (6 points or more) of a screening test must be noted in the medical records. The following actions are then recommended:

discuss the result of the screening test with the patient,

if the patient agrees, inform relatives about the diagnosis and treatment plan,

assess the level of support in the patient’s immediate environment,

inform the patient about possible options for further treatment (psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy),

suggest a plan of further proceedings – implementation of pharmacotherapy/referral to a psychiatrist/ psychologist.

Coordinated care of a patient with diagnosed depression is recommended in cooperation with specialist psychiatrists and psychologists.

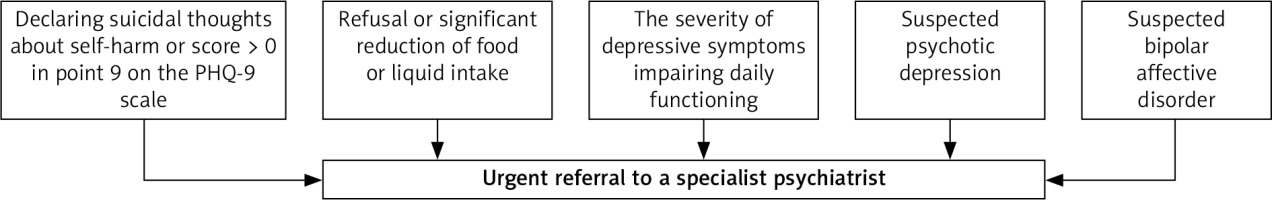

In the following cases, the patient should be referred urgently to a psychiatric consultation:

declaring suicidal thoughts and tendencies (or a score > 0 in point 9 on the PHQ-9 scale),

the severity of depressive symptoms, clearly impairing their daily functioning,

suspected psychotic depression,

suspected bipolar affective disorder,

when a patient refuses or significantly reduces meal or fluid intake (Figs. 2, 3).

[i] Note: In order to establish the diagnosis, it is necessary to determine the persistence of the symptoms for a period of at least 2 weeks, although this period may be shorter if the symptoms reach very high intensity and grow rapidly. At least 2 basic symptoms (reduced mood does not have to be one of them) and 2 additional symptoms must be found. In the case of depressive disorders that do not meet the recognition criteria for a depressive episode, e.g. when there is only one symptom from the list of basic symptoms, other depressive disorders should be considered (e.g. depressive reaction or mixed depressive-anxiety disorders).

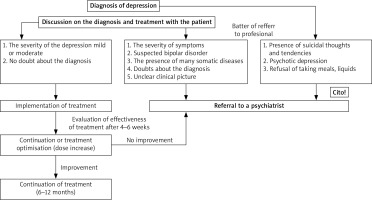

Recommendations for the treatment of depression and further management of an adult patient with diagnosed depression

The choice of an antidepressant should take into account the following: clinical features of depression, adverse reaction profile, coexisting somatic diseases, and all drugs taken.

In mild to moderate severity of symptoms, physicians may start the antidepressant treatment.

The patient should be referred directly to a psychiatrist in the case of doubts concerning the diagnosis, difficulties in establishing pharmacological treatment, when there is significant aggravation of symptoms, when it is a subsequent episode of depression, in the case of coexistence of other mental disorders (including alcohol dependence and sedative, sleeping pill, or other psychoactive substance abuse) or with coexistence of many somatic diseases.

In the situations listed above that require urgent specialist consultation, it is advisable to refer to a specialist psychiatrist without delay.

Antidepressants from the SSRI group are recommended as first-line drugs.

In the case of depression with sleep disorders and decreased appetite, treatment with mianserin or mirtazapine may be considered. In cases with sleep disorders, depression with anxiety, or anxiety disorders, trazodone or agomelatine may also be considered.

The drug should be administered in therapeutic doses.

It is recommended that the patient be informed about possible mild and transient side effects, which may occur during the first week of pharmacotherapy treatment, as well about the expected time of treatment, after which improvement may be expected (3–6 weeks).

If there are severe side effects, it is recommended that changing the medicine or referring patient to a psychiatrist be considered.

The aim of treatment is to achieve functional improvement, i.e. to return to pre-disease function.

The efficacy of antidepressant treatment should be assessed after 4–6 weeks.

If the mental state improves, antidepressant treatment should be continued for 6–9 months.

In the case of lack of response to treatment, it is advisable to verify the diagnosis and the patient’s compliance.

In the case of lack of effectiveness of treatment after 4–6 weeks, it is advisable to optimize the treatment (increase the dose) or refer to a psychiatrist.

Discontinuation of antidepressant treatment should be preceded by a reassessment of the patient’s mental state and an interview about the patient’s current life situation (withdrawal should be carefully considered if there are environmental risk factors for relapsing depression, such as difficult life circumstances).

The drug should not be discontinued suddenly; a slow dose reduction is recommended.

At each stage of treatment, it is advisable to consider the recommendation of psychotherapeutic interventions (in mild depression, – as the sole form of treatment, in more severe depressive symptoms – as additional treatment alongside pharmacotherapy) (Fig. 4).