Summary

A persistent patent foramen ovale (PFO) is a congenital heart defect that occurs in nearly 30% of the population, and its presence is associated with the risk of crossed embolism and thus stroke, especially cryptogenic stroke. Studies show that this defect is often accompanied by endothelial dysfunction. In our study, we focused on examining and comparing biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction between patients with PFO and post-stroke cerebrovascular disease and patients without PFO and without a history of a stroke episode. Post-stroke patients with PFO and had significantly higher serotonin levels compared to the control group. Moreover, the length and width of the PFO canal did not correlate with serotonin levels, indicating that regardless of the size of the leak, serotonin levels are significantly elevated, which may reflect the thrombotic and ischemic potential of patients.

Introduction

A persistent patent foramen ovale (PFO) is a congenital heart defect, a form of preserved interatrial communication. After birth, it closes within 1 year [1, 2] through the pressure changes that occur. In about 20–28% [3] of people, this process does not occur completely, resulting in the formation of a channel between the primary and secondary septum.

The discussion on the relationship between the presence of PFO and thromboembolic complications, including the most serious one – stroke – has been ongoing for many years [4, 5]. The concept of crossed (paradoxical) embolism has been documented in the literature [6, 7]. This results in embolic complications, including transient ischemic attack, or stroke. In addition, it appears that PFO-related strokes are not solely due to crossed embolism. The canal itself is a potentially thrombogenic surface where de novo thrombus formation can occur.

Among strokes, we distinguish cryptogenic strokes, i.e. ischemic strokes of the brain with no other identifiable cause (embolic stroke of undetermined source – ESUS). In patients < 55 years of age, they account for almost half of all ischemic strokes. Moreover, in these patients, PFO is found as much as 40–61% of the time, which may indicate its important role in the pathogenesis of cryptogenic strokes [8, 9].

The European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) recommends interventional PFO closure for secondary prevention of stroke in patients < 60 years of age, after thorough neurological consultation and after exclusion of other possible causes, and when anatomical or clinical risk factors are present. However, given the prevalence of this defect and its clinical importance, it seems extremely important to look for risk factors in patients with PFO that will support the decision to close the defect after a stroke episode, or by which it will be possible to identify vulnerable patients who may benefit from defect closure and protect them from a primary stroke incident and thus disability or death.

There are data indicating that patients with PFO have endothelial dysfunction more often than in the general population. This may increase thrombogenic potential and contribute to the formation of embolic material and an ischemic episode. One marker of endothelial dysfunction is serotonin, the levels of which may be elevated in patients with PFO due to its passage through the patent foramen ovale instead of into the lungs, where it is physiologically degraded. Its elevated levels may also be a cause of migraine with aura, which is more common in people with PFO. Given this, we decided to investigate whether endothelial dysfunction is a significant risk factor for cerebral embolism in patients with patent foramen ovale.

Aim

To investigate the potential association between endothelial dysfunction and the occurrence of cryptogenic stroke in patients with PFO, compared with patients without PFO and without a history of cryptogenic stroke.

Material and methods

The study recruited 79 patients, male and female, who underwent PFO closure between 2009 and 2021 within the Clinical Department of Cardiovascular Diseases of the John Paul II Specialized Hospital of Krakow, Poland. All patients recruited into the study group had a history of cryptogenic stroke. In addition, 79 patients (males and females) younger than 55 years were recruited as a control group who had previously undergone transesophageal echocardiography for indications other than assessing the presence of PFO, who did not have PFO detected, and who had no history of a cryptogenic stroke episode. The “other indications” listed above are refractory severe migraine headaches, verification of a leaky heart defect by transesophageal echocardiography and vascular lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain.

Inclusion criteria for the study group included cryptogenic stroke occurring under the age of 55 confirmed by an epicardial report from the Stroke Unit and informed consent from the patient to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were: diagnosed supraventricular tachyarrhythmia, endocrine disorders, known coagulation disorders or pregnancy. Patients who were slightly over the age of 55 and who had an episode of cryptogenic cerebral stroke before that age, after a thorough clinical evaluation, were also included in the study.

All patients in the study group underwent the same diagnostic procedures that are used in the routine diagnosis of cryptogenic stroke of unknown cause, extended by additional laboratory tests. Each patient underwent a detailed history and physical examination. Transthoracic echocardiography and transesophageal echocardiography were performed. In addition, standard laboratory tests were performed, extended by analysis of markers of endothelial dysfunction: serotonin levels, homocysteine and factor VIII.

In patients in the control group, laboratory tests were performed to assess serotonin and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels.

History and physical examination

Each patient was interviewed based on a standardized questionnaire, including, among other things, data on the current course of the disease, treatment and chronic diseases. A detailed physical examination was also performed, including, in particular, cardiovascular, neurological and anthropometric examinations.

Transthoracic echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) was performed by an experienced echocardiographer using a PHILIPS Epiq 7 c ultrasound machine. Measurements were performed according to the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC, European Society of Cardiology). Left ventricular systolic and diastolic structure and function, right ventricular systolic function, assessment of left atrial volume and function, atrial septum and atrial septal leakage and the likelihood of pulmonary hypertension were evaluated.

Transesophageal echocardiography

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) was performed by an experienced echocardiographer using a PHILIPS Epiq 7 c ultrasound machine. The atrial septum and the presence of a persistent oval opening were evaluated. The length and width of the persistent oval opening were measured. The leakage at its level was then checked using the color Doppler option. The leakage of contrast bubbles between the right and left atrium was analyzed, both spontaneously and during the Valsalva maneuver. For the assessment of the leak, 9 ml of physiological saline mixed with 1 ml of blood was used. Three beat cycles were analyzed. The assessment of the PFO leak was performed twice times. The PFO lumen dimensions were analyzed in 2D mode. The leak was considered significant or not. Routinely, the examination also included visualization of the pulmonary vein runoff, the width of the pulmonary trunk and evaluation of the left atrial appendage.

Laboratory tests

Basic laboratory parameters such as glucose, lipid profile, CRP, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and international normalized ratio (INR) were analyzed. Activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) values were not analyzed due to insufficient data. Blood counts were analyzed, with a focus on platelet parameters. In addition, for the purpose of the study, serotonin levels, a marker of endothelial dysfunction, as well as homocysteine and factor VIII levels, were analyzed in each study. To analyze the concentration of serotonin, homocysteine and factor VIII, an immunoenzymatic test was carried out using an ELISA test (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay). Blood for laboratory tests was collected before the PFO closure procedure.

Statistical analysis

The data obtained from the survey were collected in a database prepared for this purpose, and statistical analysis was carried out. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess conformity to a normal distribution. The mean values of continuous variables between the two groups were compared using Student’s t-test. To compare continuous variables with nonparametric distribution, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. Univariate linear regression analysis was used to identify relationships between quantitative variables, and univariate logistic regression analysis was used between qualitative variables. Correlations between continuous and qualitative variables were performed using Pearson and Spearman tests. Regression models were internally validated by calculating the coefficient of determination (R2) and mean absolute error. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS software package.

Results

Seventy-nine patients were recruited to the study, including 51 (64.65%) women and 28 (35.44%) men, whose mean age was 48.34 ±13.13 years. The patients’ mean body mass index (BMI) was 25.80 ±4.28 kg/m2.

The most common chronic disease observed was hyperlipidemia, which was present in 39 (49.37%) patients. Hypertension was present in 19 (24.05%) patients, nicotinism in 8 (10.13%), type 2 diabetes in 2 (2.53%) patients, chronic kidney disease in 1 (1.26%) patient, coronary artery disease in 3 (3.80%) patients and migraine in 22 (27.85%) patients. All participants had a history of cryptogenic stroke, while 13 (16.46%) of them were additionally diagnosed with a past transient ischemic attack (TIA) episode.

No significant abnormalities were observed on echocardiography. The median values of left atrial size and area were 33 mm and 17 cm2, respectively. The median left ventricular ejection fraction, calculated by the SIMPSON method, was 65%. Transesophageal echocardiography was used to analyze the morphology of the PFO channel. Its median length was 13 mm, while its width was 3 mm. There were no significant abnormalities in baseline laboratory tests. The values of fasting glucose, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, eGFR, TSH and INR were analyzed. Blood morphology components including hemoglobin, leukocyte and platelet count, as well as platelet distribution width (PDW) and mean platelet volume (MPV), were also analyzed, and their mean values were also not different from normal. Additional laboratory tests included analysis of serotonin, homocysteine and factor VIII as markers of endothelial dysfunction (Table I). Factor VIII and homocysteine values did not deviate from normal (N: 70–150% and N: 3.0–15.0 µmol/l, respectively). However, a significant increase in serotonin values was observed in the study group (1645.55 ±801.26 ng/ml) (Table II).

Table I

Correlation between serotonin levels and levels of homocysteine, factor VIII, CRP and platelet parameters in patients in the study group

| Parameter | Serotonin concentration [ng/ml] | |

|---|---|---|

| r | P-value | |

| Platelets [103/µl] | 0.16 | 0.17 |

| PDW [fl] | 0.02 | 0.86 |

| MPV [fl] | 0.11 | 0.34 |

| Factor VIII [%] | 0.21 | 0.20 |

| Homocysteine | 0.01 | 0.97 |

| CRP [mg/l] | 0.01 | 0.94 |

Table II

Echocardiographic and laboratory parameters in patients in the study group

[i] Q1 – first quartile, Q3 – third quartile. LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction, PFO – patent foramen ovale, LDL – low-density cholesterol, HDL – high-density cholesterol, TG – triglycerides, eGFR – estimated glomerular filtration rate, TSH – thyroid-stimulating hormone, INR – international normalized ratio, PDW – platelet distribution width, MPV – mean platelet volume, CRP – C-reactive protein.

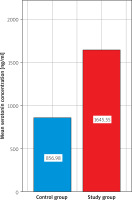

There was a statistically significant difference between serotonin levels in the study group and the control group (1645.55 ±801.26 vs. 856.98 ±781.63; p < 0.01). There was no statistically significant difference in CRP values between the control group and the study group (4.00 vs. 4.00; p = 0.77) (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Comparison of mean serotonin concentration [ng/ml] between the control group and the study group

Correlation and univariate linear regression analyses were performed to assess the relationship between serotonin concentration and channel length and width. The analysis showed no statistically significant relationship between the width (R = 0.08, R2 = 0.01; p = 0.47) and length (R = 0.08; R2 = 0.01; p = 0.45) of the PFO channel and serotonin concentration. There was also no correlation between serotonin levels and levels of homocysteine, factor VIII, CRP and platelet parameters (p = NS) (Table I). The vast majority of shunts were induced during the Valsalva maneuver. Therefore, the type of RA-LA shunt was not included in the statistical analysis.

Given the presence of migraine in 27.85% of patients, univariate logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the relationship between the presence of migraine and serotonin levels. No statistically significant relationship was found in this case (R = 0.02, p = 0.76, OR = 1.000, 95% CI: 0.999–1.001).

Discussion

The results of the above publication indicate a significantly increased serotonin concentration among patients with PFO with a history of ischemic stroke compared to patients without PFO and without a history of ischemic stroke. Additionally, no correlation was found between the parameters of the patent canal ovale and serotonin concentration, which may be important information in clinical practice.

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine), is an amine formed from tryptophan. In the cardiovascular system, it is stored mainly in platelets. It is a vasoactive, prothrombotic substance that accelerates the progression of atherosclerosis by promoting platelet aggregation, vasoconstriction and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells [10]. Its function is due, among other things, to serotonin (SERT) transporters present on platelets, but also in neurons, adrenal glands, neurons, the heart, and blood vessels [11]. Polymorphisms of the aforementioned transporters may predispose to cardiovascular events, including stroke. A study by Mortensen et al. [12] revealed a lower risk of ischemic stroke/TIA in individuals with the SERT genotype with higher expression. Serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) drugs appear to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events [13–15]. Serotonin is physiologically degraded within the lungs.

Due to the presence of PFO, in situations of increased pressure in the right heart cavities, serotonin passes from the right to the left atrium, thus avoiding degradation in the lungs, which leads to an increase in its concentration in the higher circulation, among others, within the vessels of the central nervous system [16]. This can result in increased platelet aggregation and vasospasm leading to ischemic episodes in the brain. An important issue is the potential decrease in serotonin levels after PFO closure. Ning et al. [16] described its decrease after the procedure to close the defect in question.

Patients with PFO also showed a difference in platelet parameters compared to patients without PFO. A higher MPV was noted in this group, suggesting greater platelet reactivity, as well as a propensity for thrombosis [17–19]. PFO closure has been shown to reduce MPV values [20]. Our study did not show higher MPV values or a correlation between MPV and serotonin levels; however, due to the lack of MPV values in the control group, it is impossible to show a difference between the groups. Given the physiological relationship between serotonin and platelets, it is possible that a reduction in serotonin leakage after PFO closure results in lower platelet activation and reactivity due to lower serotonin concentrations.

An important point raised in the study is the analysis of the relationship between the width and length of the PFO canal and serotonin concentration in patients in the study group, for which no statistically significant association was found. However, we consider this a very important observation, since the lack of correlation between PFO dimensions and serotonin levels indicates that these parameters do not affect serotonin levels in patients with PFO. Therefore, it can be assumed that even a small defect in the atrial septum can cause a significant increase in serotonin values and thus thrombogenic potential in patients with PFO. Notably, Węglarz et al. reported that PFO channel dimensions and the size of the right-left leak in combination with certain demographic and clinical factors were associated with ischemic neurological incidents in patients with PFO [21]. Thus, PFO dimensions may not be related to serotonin levels, but may be related to the risk of ischemic neurological incidents in patients with PFO, for example, by increasing the risk of paradoxical embolism, which does not exclude the existence of other thromboembolic risk factors.

The existence of a correlation between PFO and elevated serotonin levels and coexisting migraine with aura is also debatable. Serotonin receptors 5-HT1B and 5-HT1D, which are also located in the vessels of the central nervous system, play an important role in the pathogenesis of migraine with aura. It has been shown that elevated levels of serotonin can increase the occurrence of migraine by inducing transient ischemia [22]. In the general population, the number of patients facing migraine is about 10%, mainly between 20 and 50 years of age. Due to the presence of migraine in 27.85% of the subjects in the above study, which is almost 3 times higher compared to the population, a logistic regression analysis was performed, which showed no significance between serotonin levels and the presence of migraine. However, Deepak et al. noted a correlation between high serotonin levels and migraine co-occurrence, mainly due to leakage of vasoactive substances, at the level of the cardiac atria, into the vessels of the central nervous system. Weglarz et al. observed a higher incidence of migraine in PFO patients with ischemic neurological events, and the presence of a PFO was also associated with a higher incidence of TIA, syncope, reticular Chiari and ASA, and a lower incidence in the female gender, but only in patients 45 years of age or younger [23].

Markers of endothelial dysfunction in the above study, in addition to serotonin, include CRP, homocysteine and factor VIII. While the role of serotonin and its levels in patients with PFO and the potential reduction in its levels after defect closure are documented in studies, the role of the other markers is not clear. Lantz et al. found no reduction in markers of endothelial dysfunction, such as endothelin-1, hsCRP, vWF and Hcy, after PFO closure [24]. The initial values of these markers were within normal limits. There was no statistically significant difference between CRP levels in the study group and the control group, and their levels were within the normal range. Due to the lack of factor VIII and homocysteine results in the control group, it was not possible to compare them.

Analysis of endothelial dysfunction can also be done by functional tests such as flow-mediated dilation (FMD) [25]. FMD was found to be significantly lower in post-stroke patients compared to non-stroke patients. In addition, post-stroke PFO patients had significantly lower FMD parameters compared to non-stroke patients with PFO. Patients with cryptogenic stroke without PFO had significantly lower FMD values compared to non-stroke patients without PFO. This indicates the presence of significant endothelial dysfunction in this group of patients despite the discrepancy and lack of conclusive data associated with elevated markers of endothelial dysfunction.

Proper PFO closure reduces serotonin levels and provides secondary prevention of cryptogenic stroke [26, 27]. By closing the atrial septal defect, serotonin is broken down in the lungs, preventing it from entering the general circulation, thereby reducing the number of migraine attacks with aura.

The lack of a control study of serotonin after PFO closure prevents analysis of the correction of its concentration. This justifies the need for a study in this group of patients to assess serotonin levels after PFO closure surgery. Assessment of endothelial function using the above-mentioned markers is dictated by their pathophysiological role and association with the presence of PFO, as well as financial considerations, but we are no less aware of the need for further studies using markers with higher sensitivity. In order to more accurately assess endothelial dysfunction in patients with a history of PFO and stroke, studies should be conducted on a larger group of patients. Serotonin and CRP were obtained in the study and control groups, but homocysteine and factor VIII levels were analyzed only in the study group. This due to the subsequent inclusion of the above markers in the study, and the initial recruitment of a control group with which contact was difficult compared to the research group.

Conclusions

Serotonin levels appear to be significantly higher in patients with PFO after cryptogenic stroke compared with patients without PFO and no history of stroke. This may be related to both right-left leakage and concomitant endothelial dysfunction. The length and width of the PFO canal may not correlate with serotonin levels; nevertheless, based on the above results, this would indicate that regardless of the size of the leak, serotonin levels are significantly increased, potentially reflecting the thrombotic and ischemic potential of patients.