Introduction

The global prevalence of childhood obesity is constantly rising as a result of sedentary lifestyle and excessive calorie intake and results in the emergence of its metabolic comorbidities in the pediatric population – dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, diabetes type 2, hypertension, atherosclerosis and left ventricular hypertrophy [1, 2]. Rising prevalence of fatty (steatotic) liver disease among children is another problem strongly associated with obesity. Currently, it is estimated to affect nearly 10% of children, which makes it the most common childhood liver pathology [3]. Recently, experts proposed the introduction of the new term metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), which replaces the previous terms nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) [4]. Development of NAFLD/MASLD is known to be associated with metabolic syndrome components, while on the other hand it may promote diabetes type 2 and increase cardiovascular risk. Recently, researchers have shown an increased interest in a process of lipotoxicity as one of the factors leading to oxidative stress, inflammation and cell death in patients with steatotic liver. It is reported that severity of liver injury is associated not only with the amount but also the type of accumulated lipids and their interactions [5, 6]. Circulating fatty acids (FA) are among most commonly investigated molecules involved in the process of lipotoxicity [7]. Several studies have revealed that the impact of FA on metabolic syndrome depends largely on their saturation and length of the chain. Saturated fatty acids (SFA) are associated with increased cardiovascular risk and liver injury, while monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) are considered protective against steatotic liver by ameliorating blood lipid profile and decreasing insulin resistance [8]. On the other hand, the biological properties of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) seem to depend on the localization of the double bond in their backbone. N-3 PUFA were identified as anti-inflammatory and protective against cell death, while n-6 PUFA are considered to activate proinflammatory pathways [9]. Dihomo-γ-linolenic acid (DGLA) is among the most commonly investigated PUFA in metabolic syndrome and lipotoxicity. It is mostly synthesized from linoleic acid (LA) by desaturation to γ-linolenic acid by Δ6 desaturase (D6D) and further elongation. Afterwards, Δ5 desaturase (D5D) converts DGLA to arachidonic acid (AA) – a substrate for the synthesis of proinflammatory series 2 prostaglandins and leukotrienes. Recent studies, in adults, detected a strong association of increased serum concentration of DGLA with obesity and other components of metabolic syndrome such as insulin resistance and diabetes type 2 [10, 11]. Interestingly, it was found that high serum levels of DGLA may be observed up to ten years before the onset of metabolic syndrome and decrease after life-style modification [10]. Moreover, there was a strong association between concentrations of DGLA and inflammatory and endothelial activation markers such as interleukin 6 (IL-6) or soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1) [12]. Recent evidence suggests that a similar observation can be made in the pediatric population – the level of DGLA was positively associated with abdominal obesity, insulin resistance, and increased concentrations of triglycerides (TG) and cholesterol [13, 14]. Previous studies in adults have reported the link between high DGLA levels and hepatic steatosis [15]. Moreover, Jiang et al. reported significantly higher serum DGLA concentrations in adults with NAFLD and demonstrated its potential value as a serum biomarker of fatty liver [16]. However, only a few studies have been conducted on the association of DGLA with hepatic steatosis in the pediatric population. Hua et al. reported high levels of DGLA in schoolchildren with high-grade liver steatosis [17]. Therefore, the main purpose of this study was to evaluate serum concentrations of dihomo-γ-linolenic acid and associated long chain n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (linoleic, arachidonic acid) together with estimated desaturase activities and potential correlations with anthropometric measurements, parameters of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism and the degree of liver steatosis in children with obesity and MASLD.

Material and methods

The prospective study included 57 children (46 males and 11 females) aged 7 to 17 years (median age 12 years) with obesity (body mass index [BMI] > 95th percentile for sex and age) admitted to the department to diagnose initially suspected liver disease (elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity and/or ultrasonographic signs of liver steatosis and/or hepatomegaly). Exclusion criteria included viral hepatitis (HCV, HBV, CMV), autoimmune (autoimmune hepatitis – AIH), toxic (drug-induced liver injury – DILI), celiac disease, selected metabolic liver diseases (α1 antitrypsin deficiency, Wilson’s disease, cystic fibrosis) and type 2 diabetes. Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease was diagnosed based on the criteria proposed by Rinella et al. [4]. The reference group comprised 19 children with normal weight (BMI < 85th percentile) without any somatic organ pathology matched for age and sex. An informed consent form was signed by a parent and all subjects older than 16 years old participating in the study. The research was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Bialystok and was in line with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The anthropometric measurements (height, weight, waist circumference) were obtained from each patient, BMI was calculated, and age and gender adjustments were performed according to the OLAF growth charts [18]. Blood samples of patients were analyzed for activity of alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT), lipid profile (total cholesterol, high- and low-density lipoprotein (HDL and LDL), triglycerides), glucose and insulin levels. Homeostasis model assessment estimated insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated in each patient using Matthews et al.’s formula [19]. In each patient magnetic resonance proton spectroscopy (1HMRS) was performed using a 1.5 T scanner (Picker Eclipse) and PRESS sequencing was used for assessing the total intrahepatic lipid content (TILC) in relative units (r.u.) in comparison to the unsuppressed water signal. Water suppression was performed using the MOIST (Multiply Optimized Insensitive Suppression Train) method. A voxel of 3 × 3 × 3 cm (27 cm3) was selected in the region of the right liver lobe on the basis of T2-weighted images in the frontal and transverse planes. The voxel was localized in such a way as to avoid large vessels and bile ducts. Spectroscopy was conducted in a fasting state. The cut-off value for TILC was 55 r.u. 1HMR spectroscopy is considered to be an accurate and noninvasive method for evaluating hepatic fat content [20, 21]. Fasting blood samples used for DGLA assessment were drawn from both study and reference groups and stored after centrifugation at –80°C until analyses were performed.

Serum samples (100 μl) with the addition of an internal standard and methylation mixture (acetyl chloride, methanol, and butylhydroxytoluene) were incubated at 85ºC for 45 minutes. After incubation, 500 μl of hexane was added to each sample and mixed by vortexing. Then, the test tubes were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 3000 rpm. Finally, 100 μl of the supernatant’s upper layer was taken and analyzed. Subsequently, the individual fatty acid methyl esters were quantified according to the standard retention times using gas liquid chromatography (Hewlett-Packard 5890 Series II gas chromatograph, an Agilent J&W CP-Sil 88 capillary column (50 m × 0.25 mm inner diameter), and a flame-ionization detector (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California)). Plasma concentrations of dihomo-γ-linolenic acid, linoleic acid, and arachidonic acid were estimated and expressed in milligrams per liter of blood serum. The estimated Δ5 desaturase (D5D) activity was calculated based on the AA to DGLA ratio and the estimated Δ6 desaturase (D6D) activity based on the DGLA to LA ratio. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 13.0 software. All the parameters were expressed as median with 25th-75th percentile (quartiles Q1-Q3). Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables used in the study. Nonparametric data were compared using the Mann-Whitney two-sample test. Correlation analyses were performed using the Spearman rank-correlation test for non-parametric data and the Pearson method for parametric data. ROC analysis was performed to determine the optimal cutoff value, and AUC to determine the accuracy of DGLA concentration to detect liver steatosis in 1HMRS. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

The study group included 57 children with obesity with a predominance of males (46 males vs. 11 females). The reference group comprised 19 children (9 males vs. 10 females) with normal BMI without any somatic organ pathology. Median BMI of the study group was 27.44 (25.7-31.9) kg/m2. MASLD was diagnosed in 25 patients, which accounted for 43.9% of the study group. Nearly three quarters of children with obesity were diagnosed with insulin resistance (42 patients, 73.7%). General characteristics of the whole study group and two subgroups – obese children with MASLD and obese children without MASLD (non-hepatopathic obese patients) – are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Characteristics of the whole study group (n = 57), obese children with MASLD (n = 25) and obese children without MASLD (n = 32)

Children with MASLD had significantly higher BMI (p < 0.05), waist circumference (p < 0.05), ALT activity (p < 0.001), GGT activity (p < 0.001) and TILC (p < 0.01) in comparison to obese children without MASLD.

DGLA concentration was significantly elevated in the study group compared to the reference group (p < 0.01). Similar observations were made in the subgroup of obese children with MASLD when compared to the reference group (p < 0.001). Moreover, DGLA concentration was significantly higher in a subgroup of children with MASLD in comparison to the rest of obese children (p < 0.05). The difference between the subgroup of children without MASLD and the reference group was not significant (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

DGLA concentration in the subgroup of children with obesity and MASLD, children with obesity but without MASLD and the reference group. Data shown as median (Q1, Q3). Significant differences between the groups are shown as *p < 0.01

The DGLA/LA ratio (surrogate parameter for D6D activity) was significantly elevated, while the AA/DGLA ratio (surrogate parameter for D5D activity) was significantly lower in obese subjects compared with the reference group. Detailed results are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Differences between serum fatty acid concentrations (DGLA, LA, AA) (mg/l) and estimated D5D and D6D activity in the study group, the group of children with obesity and MASLD and the reference group

| Parameter | Study group (n = 57) Median (Q1-Q3) | Obese children with MASLD (n = 25) Median (Q1-Q3) | Reference group (n = 19) Median (Q1-Q3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DGLA (mg/l) | 30.29 (23.80-40.76)b | 34.09 (28.77-43.85)b | 23.26 (21.59-28.19) |

| LA (mg/l) | 665.3 (590.4-820.3) | 704.7 (590.4-877.0) | 583.5 (524.7-713.3) |

| AA (mg/l) | 124.1 (95.3-142.5) | 125.0 (109.0-155.9) | 130.9 (119.9-161.8) |

| AA/DGLA (D5D activity) | 3.95 (3.21-4.79)b | 3.82 (3.18-4.37)b | 5.51 (4.88-6.68) |

| DGLA/LA (D6D activity) | 0.05 (0.04-0.05)a | 0.05 (0.04-0.06)a | 0.04 (0.03-0.05) |

There were significant, positive correlations between DGLA concentration and activities of ALT (R = 0.35, p < 0.01), AST (R = 0.29, p < 0.05), γ-glutamyl transferase (R = 0.39, p < 0.01), concentrations of total cholesterol (R = 0.5, p < 0.001), LDL cholesterol (R = 0.34, p < 0.05), and triglycerides (R = 0.60, p < 0.001) and total intrahepatic lipid content (TILC) (R = 0.42, p < 0.01). LA and AA concentrations were significantly, positively correlated with total cholesterol (R = 0.62, p < 0.001 and R = 0.59, p < 0.001 respectively), LDL cholesterol (R = 0.47, p < 0.001 and R = 0.49, p < 0.001 respectively) and triglycerides (R = 0.55, p < 0.001 and R = 0.30, p < 0.05 respectively). Moreover, there was a significant, negative correlation between estimated D5D activity and triglycerides level (R = –0.35, p < 0.01) and a positive correlation between estimated D6D activity and BMI (R = 0.31, p < 0.05), activities of ALT (R = 0.36, p < 0.01) and AST (R = 0.29, p < 0.05) and TILC (R = 0.43, p < 0.01).

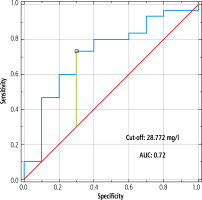

The ability of DGLA concentration to detect liver steatosis was significant (AUC = 0.72, p < 0.05, sensitivity = 73.3%, specificity = 70%, cut-off > 28.772 mg/l) (Fig. 2).

Discussion

In this study, the main aim was to assess the serum concentration of dihomo-γ-linolenic acid and associated long chain n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (linoleic, arachidonic acid) together with estimated desaturase activities in obese children with liver steatosis in relation to their clinical and laboratory data. This study has shown significantly elevated concentration of DGLA in children with obesity in comparison to children with normal weight. Moreover, DGLA concentration was positively correlated with elevated liver function tests, parameters of lipid profile and total intrahepatic lipid content. In accordance with the present results, previous studies have demonstrated significantly elevated DGLA concentrations in obese individuals. Ni et al. presented the results of the metabolomics analysis of serum samples of subjects from four independent studies. DGLA was considered a significant marker to distinguish metabolically healthy and unhealthy individuals. They also noted that DGLA levels decreased after weight loss interventions, both dietary and surgical [10]. The study conducted by Tsurutani et al. on adults with diabetes type 2 also reported higher DGLA concentrations in obese individuals. DGLA concentration was strongly correlated with ALT activity and body fat percentage [22].

In the current study children with obesity demonstrated significantly increased estimated D6D activity and significantly decreased estimated D5D activity. There was a significant negative correlation between estimated D5D activity and triglycerides and a positive correlation between estimated D6D activity and BMI, aminotransferase activity and total intrahepatic lipid content. The present findings seem to be consistent with an elegant systematic review and meta-analysis performed by Fekete et al., who found a significantly higher DGLA concentration and DGLA/linoleic acid ratio and significantly lower arachidonic acid/DGLA ratio in overweight or obese subjects compared with controls [23]. Similar observations were made by Warensjö et al., who reported an association of elevated DGLA concentration and altered desaturase activities (increased D6D and decreased D5D) with excessive weight [24]. These observations are supported by Kawashima et al., who noted higher estimated D6D activity and lower D5D activity in obesity and metabolic syndrome. Moreover, estimated D5D activity was considered to be a predictive factor for abdominal obesity [25]. A cross-sectional study conducted with Spanish premenopausal women demonstrated a significant positive correlation between DGLA concentration and total fat percentage, which corroborates our findings. Similarly to our study, estimated D6D activity was positively associated with BMI and total fat percentage, which is consistent with our findings [26].

A few studies have been conducted in the pediatric population, and the results seem to be consistent with the present findings. Xu et al.’s study showed a significant decrease in DGLA concentration after 4 weeks of intervention with exercise and dietary restriction in obese adolescents [27]. Significantly higher DGLA concentration and elevated D6D activity in obese children in comparison to non-obese children were observed by Okada et al. [28]. A recent study by Hua et al. involved a group of schoolchildren aged 7-18 years who were divided into groups based on the presence of excessive weight and abdominal obesity. DGLA concentration was significantly higher in obese and overweight children in comparison to normal-weight controls. Moreover, elevated DGLA levels, as well as increased D6D and decreased D5D activities, were strongly correlated with hypertriglyceridemia and metabolic risk scores, which led to the conclusion that these parameters are associated with abdominal obesity and increased metabolic risk in children who are obese and overweight. These findings are in agreement with our results. Similarly, in a study by Steffen et al. overweight adolescents were found to have significantly higher DGLA concentrations, as well as elevated D6D and lower D5D activity, in comparison to individuals with normal weight, which is in line with our findings. Moreover, consistent with our results, DGLA levels and increased D6D activity correlated positively with triglyceride and total cholesterol concentrations [29].

The second major finding was that DGLA concentration was significantly increased in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in comparison to the group of children with obesity but without MASLD and the reference group. Moreover, children with MASLD has significantly decreased estimated D5D activity and elevated estimated D6D activity compared to the reference group. There was a significant, positive correlation between DGLA concentration and elevated estimated D6D activity with aminotransferase activities and total intrahepatic lipid content. Another interesting finding to emerge from this study is the significant ability of DGLA concentration to detect liver steatosis in children. These findings are in agreement with Matsuda et al.’s study conducted on adults with metabolic syndrome components. They detected a significant correlation of DGLA level and low D5D activity with liver steatosis and considered high DGLA level and low D5D activity useful markers predicting hepatic steatosis [15]. The results of Fridén et al. are partially consistent with our findings. In their recent study they observed an inverse association of linoleic acid and Δ5 desaturase index and direct associations of dihomo-γ-linolenic acid, arachidonic acid and Δ6 desaturase index with liver fat [30]. Our study did not reveal a correlation of LA, AA and estimated D5D activity with total intrahepatic lipid content. It may be related to the small number of subjects in the examined groups, and therefore the analyses should be repeated in larger groups. Jiang et al. also found a significantly increased DGLA concentration in adult individuals with NAFLD and confirmed its usefulness to predict liver steatosis [16]. The results of two studies conducted in the pediatric population are consistent with our results. Children with steatotic liver (NAFLD) had significantly higher concentration of serum DGLA as well as elevated estimated D6D and decreased estimated D5D activity in comparison to healthy controls [17, 31]. In contrast to our findings, both studies detected significantly lower LA concentrations and higher AA concentrations in a group of children with NAFLD. Our research did not reveal significant differences in LA and AA concentrations between the groups. A possible explanation for this inconsistency is the small group sample.

In the literature, there are only a few studies investigating n-6 PUFA and desaturase activities in the pediatric population. The novelty of these findings is the key strength of our research. This is the first study reporting serum concentration of dihomo-γ-linolenic acid and associated long chain n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (linoleic, arachidonic acid) together with estimated desaturase activities in obese children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Finally, some important limitations need to be considered. First, the number of individuals recruited to the study group is quite small. Moreover, the concentrations of n-6 PUFA and estimated activities of desaturases were assessed in children who already had steatotic liver disease; therefore the cause and effect relationship between development of MASLD and alteration in n-6 PUFA concentrations still remains unknown. Larger studies with a prospective design are needed to confirm our results.

Conclusions

Serum DGLA levels may be considered as a potential novel noninvasive biomarker for liver steatosis detection in children. The differences in the serum concentration of DGLA and associated long chain n-6 PUFA between the groups and correlations found between their concentrations and other parameters suggest their potential role in pathogenesis and development of MASLD in children with obesity.