Introduction

Cholestasis is a medical condition characterized by disruptions in the bile flow. Cholestasis is linked to various liver diseases [1-3]. Physiologically, the bile, which consists of various chemicals such as bile acids and bilirubin, plays a crucial role in the digestion and absorption of nutrients from the small intestine. In cases of cholestasis, these bile components (e.g., potentially cytotoxic bile acids) accumulate in the liver and eventually enter the bloodstream. While cholestasis primarily affects the liver, other tissues such as skeletal muscle, kidney, brain, heart, and lungs can also be damaged by the toxic bile constituents during cholestatic liver disease [3-6].

Cholemic nephropathy (CN), also known as bile cast nephropathy, is a form of kidney injury that occurs in the setting of cholestasis. Cholemic nephropathy could manifest as acute kidney injury (AKI) or chronic kidney disease (CKD) in patients with underlying liver diseases, such as primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, or drug-induced liver injury [5, 7-12]. It has been well documented that CN in cholestatic/cirrhotic patients is a prevalent and acute complication with a poor prognosis [9-11]. Cholemic nephropathy is associated with severe interstitial renal inflammation, bile/protein cast formation, and tissue fibrosis. These events could finally lead to renal failure [8, 13-16]. Although the precise mechanisms of CN at the molecular level need more investigations to be clarified, numerous studies have indicated that oxidative stress and its associated events, mitochondrial dysfunction, apoptotic cell death, and immune system-mediated response are crucial factors in development of this complication [17-20]. It has been reported that antioxidant systems are impaired, and mitochondrial function and energy metabolism are disturbed in the kidney tissue during CN [21-25]. Moreover, inflammatory response and cytokines also play an essential role in the pathogenesis of renal fibrosis during CN [18, 24, 26]. Therefore, targeting oxidative stress and inflammation could be viable in managing CN.

Sildenafil is an inhibitor of the phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) enzyme commonly used for erectile dysfunction. Meanwhile, several other pharmacological effects of sildenafil have been identified. The protective effects of sildenafil on the liver, lung, and central nervous system have been repeatedly mentioned in experimental and/or clinical studies [27, 28]. The effect of PDE5 inhibitor drugs such as sildenafil on the kidney is also one of the most interesting pharmacological properties of these drugs, attracting the attention of many researchers [29-31]. It has been found that sildenafil can protect kidneys from a wide range of xenobiotics [29, 30]. This drug has also demonstrated nephroprotective properties in several kidney diseases [31-33]. Interestingly, some clinical trials have also highlighted the nephroprotective properties of PDE5 inhibitors. In these studies, drugs such as sildenafil exerted significant nephroprotective effects in patients undergoing nephrectomy, those with postcardiac surgery-induced acute kidney injury, and individuals with valvular heart disease-related renal impairment [34-37]. All these data underscore the value of sildenafil in protecting renal tissue and evaluating its nephroprotective properties/mechanisms in various experimental models.

Several mechanisms have been suggested for the renoprotective properties of sildenafil. The effects of sildenafil in improving renal blood flow, blunting oxidative stress, modulating inflammatory responses, and enhancing mitochondrial function seem to play a role in the mechanism of its protective properties [30, 38-40]. As mentioned, oxidative stress and the inflammatory response play an essential role in the pathogenesis of CN [41]. Hence, the current study was designed to assess the potential protective properties of sildenafil in an animal model of CN.

Material and methods

Reagents

Trichloroacetic acid, sodium acetate, n-chloro tosylamide (chloramine-T), n-propanol, p-dimethyl amino benzaldehyde, sodium citrate, dithiothreitol, 2,4,6-Tri(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine, thiobarbituric acid, ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid (EDTA), sucrose, meta-phosphoric acid, and 2-amino-2-hydroxymethyl-propane-1,3-diol-hydrochloride (Tris-HCl) were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Sildenafil citrate, dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DFC-DA), and reduced glutathione (GSH) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Kits for evaluating cholestatic liver injury and renal dysfunction biomarkers were purchased from Pars-Azmoon (Tehran, Iran).

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (n = 40, 250-300 g weight) were obtained from Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. Animals were housed in a standard environment (temperature of 23 ±1°C, 43 ±2% relative humidity, and a 12 h light : 12 h dark photoschedule). Animals had free access to a typical rodent’s diet (Behparvar, Tehran, Iran) and tap water. All experiments were conducted in conformity with the guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals and approved by the ethics committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran (IR.SUMS.REC.1399.1344).

Bile duct ligation surgery for cholestasis induction

Animals were anesthetized (a mixture of ketamine : xylazine : acepromazine; 70 : 10 : 2 mg/kg, i.p.), and the laparotomy was performed through the linea alba. The common bile duct was identified, doubly ligated (4/0 silk suture), and cut between the ligatures [42]. The sham operation consisted of laparotomy and bile duct identification and manipulation without ligation [42].

Treatments

Rats (n = 40; 8 animals/group) were treated as follows: 1) sham-operated (vehicle-treated; 2.5 ml/kg; oral, for 14 consecutive days), 2) bile duct ligation (BDL), 3) BDL + sildenafil citrate (5 mg/kg, i.p., for 14 consecutive days), 4) BDL + sildenafil citrate (10 mg/kg, i.p., for 14 consecutive days), and 5) sildenafil citrate (20 mg/kg, i.p., for 14 consecutive days). Sildenafil doses (5, 10, and 20 mg/kg) were selected based on previous studies on the nephroprotective properties of this drug [43, 44]. The time frame (14 days) of investigation was selected based on previous studies that indicated appropriate induction of cholestasis and the involvement of organ injury (including the renal tissue) in the BDL model [45-47].

Serum and urine biochemistry

Urine samples were collected during animal handling (300 µl), diluted with 300 µl of ice-cold (4°C) normal saline, and centrifuged (3000 g, 5 min, 4°C). Then, the clear supernatant was collected and used for urinalysis [48]. Blood samples were collected from the abdominal aorta in gel-coated tubes and centrifuged (3000 g, 20 min, 4°C) to prepare serum. Commercial kits (Pars-Azmoon, Tehran, Iran) and a Mindray BS-200 auto-analyzer were used to measure serum and urine biomarkers of organ injury. Serum bile acids were measured using a commercial kit (EnzyFluo Bile Acid Assay Kit, BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA 94545, USA).

Tissue histopathology and organ weight index

Tissue samples were fixed in a buffered formalin solution. Then, paraffin-embedded sections of the kidney tissues (5 µm) were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Renal cast formation was monitored by Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) staining [49]. Kidney fibrosis was determined by Masson’s trichrome staining [50, 51]. ImageJ software was used to quantify the fibrotic area in trichrome staining images (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nLfVSWcxMKw). The organ weight indices for the liver, spleen, and kidney were assessed as organ weight index = [wet organ weight (g)/body weight (g)] × 100.

Reactive oxygen species formation

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) in kidney samples were measured using 2’,7’ dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA). Kidney tissue (500 mg) was homogenized in 40 mM Tris-HCl buffer. Then, 100 µl of tissue homogenate was mixed with 900 µl of Tris-HCl buffer and DCF-DA (final concentration 10 µM). After 10-minute incubation at 37°C in the dark, fluorescence intensity was recorded using a fluorimeter at 485 nm excitation and 525 nm emission [52, 53].

Lipid peroxidation in the kidney

The thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) test was used to assess lipid peroxidation in the kidney tissue of cholestatic rats. The reaction involved 500 µl of tissue homogenate in Tris-HCl buffer mixed with thiobarbituric and phosphoric acid. The mixture was heated at 100°C for 45 minutes, cooled, then mixed with n-butanol and centrifuged (3000 g, 5 min). The absorbance of the n-butanol phase was measured at 532 nm using a plate reader [52, 53].

Protein carbonylation

Oxidative damage to renal proteins in cholestatic rats was assessed using 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) [54]. A tissue homogenate (10% w : v in 40 mM Tris-HCl buffer) was prepared and centrifuged, and the supernatant was treated with DNPH and incubated for one hour at 25°C (orbitally shaking incubator). After adding trichloroacetic acid, the mixture was centrifuged, and the pellet was washed with ethanol-ethyl acetate. The residue was dissolved in 6 M guanidine and centrifuged. The absorbance was measured at 370 nm using a plate reader [54].

Renal glutathione content

The DTNB (5,5’-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid) method was used to measure reduced glutathione (GSH) levels in the renal tissue [52, 53]. For this purpose, 500 µl of tissue homogenate (10% w : v in 40 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH = 7.4) was treated with 100 µl of TCA (50% w : v), mixed well, and centrifuged (16,000 g, 15 min, 4°C). Then, the supernatant was mixed with 1 ml of Tris-HCl buffer (pH = 8.9) and 100 µl of DTNB solution (0.1 M in methanol). Samples were mixed well and incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes (protected from light). Finally, the absorbance was measured at 412 nm [52, 53].

Ferric reducing antioxidant power

The freshly prepared ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) reagent consisted of acetate buffer, 40 mM TPTZ in HCl, and 20 mM ferric chloride hexahydrate. Then, 100 µl of the homogenate was mixed with 900 µl of the FRAP reagent and incubated at 37°C for 5 minutes in the dark. Finally, the absorbance was measured at 595 nm using a plate reader [52, 53].

Kidney hydroxyproline content

Kidney hydroxyproline content was measured by digesting 500 µl of kidney tissue homogenate (10% w : v in 40 mM Tris-HCl) in 1 ml of 6 N hydrochloric acid at 120°C for 24 hours. Then, a 250 µl aliquot of the digest was mixed with 250 µl of citrate-acetate buffer (pH = 6) and 500 µl of 56 mM chloramine-T solution. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes. Subsequently, 500 µl of Ehrlich reagent was added, and the mixture was incubated at 65°C for 15 minutes. Finally, the absorbance was measured at 550 nm using a plate reader [55].

Activity of antioxidant enzymes

The activity of catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and glutathione reductase (GR) was assessed using commercial kits (colorimetric) based on the manufacturer’s instructions (ZellBio, Germany). The details are available from the manufacturer’s website (https://zellbio.eu).

Inflammatory cytokines in the kidney tissue

The pro-inflammatory cytokine (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β) levels in the renal tissue were measured using commercial kits (ELISA method), according to the instructions provided by Karmania-Pars-Gene (Kerman, Iran). Briefly, 500 µl of the tissue homogenate was centrifuged (16,000 g, 10 min, 4°C), and the supernatant was used to assess pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Statistical methods

Data are given as mean ±SD (n = 8 animals/group). The data sets were compared using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc test. Renal histopathological alterations are presented as median and quartiles and were analyzed using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by the Mann-Whitney U-test. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

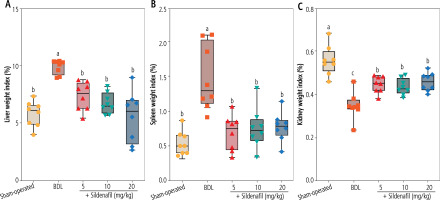

Evaluation of the organ weight indices revealed significant hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and decreased kidney weight index in cholestatic animals (Fig. 1). It was found that sildenafil (5, 10, and 20 mg/kg) significantly improved liver, spleen, and renal weight changes induced by cholestasis (Fig. 1). The effect of sildenafil on organ weight indices was not dose-dependent in the current study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Organ weight indices in cholestatic rats. Data are given as box and whiskers (min to max) for n = 8 animals/group. Data sets with different alphabetical superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05). BDL – bile duct ligation

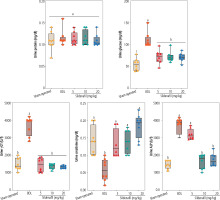

Significant alterations in serum biochemistry, including increased ALT, AST, LDH, ALP, total bilirubin, bile acids, and γ-glutamyltransferase (γGT), were evident in BDL animals (Fig. 2). Serum levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) (≈ 2 fold) and creatinine (Cr) (≈ 1.5 fold), as biomarkers of renal injury, were also significantly higher in the BDL group compared to sham-operated animals (Fig. 2). It was found that sildenafil significantly improved serum biochemical alterations induced by cholestasis (Fig. 2). The effect of sildenafil on serum biochemistry was not dose-dependent in the current study (Fig. 2). On the other hand, sildenafil had no significant impact on some serum parameters such as total bilirubin, bile acids, γ-glutamyltransferase (γGT), and ALP (Fig. 2). As the bile duct was permanently obstructed in the BDL model of cholestasis, it was expected that markers of bile duct injury (total bilirubin, bile acids, γGT, and ALP) would constantly increase in this study (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2

Serum biochemical measurements in bile duct ligation (BDL) model of cholestasis. Data are given as box and whiskers (min to max) for n = 8 animals/group. Data sets with different alphabetical superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Urinalysis of cholestatic rats revealed a significant increase in urine glucose, γGT, ALP, and Cr (Fig. 3). It was found that sildenafil (5, 10, and 20 mg/kg) significantly decreased urine biomarkers of renal injury in BDL rats (Fig. 3). The effect of sildenafil on urine biomarkers was not dose-dependent in the current investigation (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

Urinalysis of cholestatic rats. Data are given as box and whiskers (min to max) for n = 8 animal/group. Data sets with different alphabetical superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05). BDL – bile duct ligated

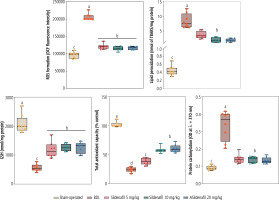

Significant increases in biomarkers of oxidative stress, including enhanced ROS formation, lipid peroxidation, protein carbonylation, and oxidized glutathione (GSSG) levels, were detected in the kidneys of BDL animals (Fig. 4). Reduced glutathione (GSH) and renal tissue antioxidant capacity were also significantly decreased in cholestatic rats (Fig. 4). On the other hand, a significant decrease in activity of the antioxidant enzymes SOD, CAT, GR, and GPx was evident in the renal tissue of cholestatic animals (Fig. 5). It was found that sildenafil significantly decreased biomarkers of oxidative stress in the kidneys of cholestatic rats (Figs. 4 and 5).

Fig. 4

Oxidative stress biomarkers in the kidney of bile duct ligated (BDL) rats. Data are given as box and whiskers (min to max) for n = 8 animals/group. Data sets with different alphabetical superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05). ROS – reactive oxygen species, DCF – 2’,7’-dichlorodihydrofluorescein, GSH – reduced glutathione, OD – optical density, TBARS – thiobarbituric acid reactive substances

Fig. 5

Activity of antioxidant enzymes in the kidney of cholestatic animals. Data are given as box and whiskers (min to max) for n = 8 rats/group. Data sets with different alphabetical superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05). BDL – bile duct ligated

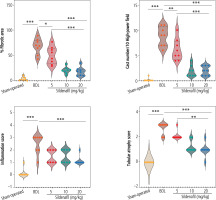

Significant interstitial inflammation and tubular atrophy were evident in the kidneys of BDL rats (Fig. 6; H&E staining and Table 1). As revealed by trichrome-Masson staining and hydroxyproline levels, biomarkers of tissue fibrosis were also significantly elevated in the renal tissue of cholestatic rats (Fig. 6 and Table 1). Significant elevation in renal cast formation was also detected in PAS staining of the renal tissue (Fig. 6 and Table 1). It was found that kidney fibrosis was decreased by sildenafil (5, 10, and 20 mg/kg) (Fig. 6 and Table 1). The effect of sildenafil on renal tissue fibrosis, cast formation, and other histopathological alterations was not dose-dependent in the current study (Fig. 6 and Table 1).

Table 1

Grade of renal histopathological changes in bile duct ligation (BDL) model of cholestasis

| Treatments | Interstitial inflammation | Tubular degeneration | Necrosis | Tissue fibrosis | Cast formation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham-operated | 0 (0, 0)# | 0 (0, 0)# | 0 (0, 0)# | 0 (0, 0)# | 0 (0, 0)# |

| BDL | 2 (2, 2) | 2 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 1) | 3 (2, 3) | 3 (3, 3) |

| BDL + Sildenafil 5 mg/kg | 1 (1, 1)# | 1 (1, 1)# | 0 (0, 0)# | 2 (1, 2)# | 2 (2, 2) |

| BDL + Sildenafil 10 mg/kg | 1 (0, 1)# | 1 (0, 1)# | 0 (0, 0)# | 1 (1, 1)# | 2 (1, 2)# |

| BDL + Sildenafil 20 mg/kg | 1 (0, 1)# | 0 (0, 0)# | 0 (0, 0)# | 1 (1, 1)# | 2 (1, 2)# |

Fig. 6

Effect of sildenafil on renal histopathological alterations in bile duct ligation (BDL) model of cholestasis. Significant tubular atrophy and interstitial inflammation were detected in the kidneys of BDL rats. The distribution of histopathological data was not normal in this study. The score of tissue histopathological alteration (non-parametric data) was analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Mann-Whitney U-test. The grades and statistical analysis methods for histopathological alterations of the kidney tissue in cirrhotic animals are represented in Table 1

Discussion

Cholestasis is characterized by the obstruction of bile flow, which leads to significant accumulation of the bile constituents (e.g., bilirubin and bile acids) in the liver [56]. Thus, the liver is the primary organ affected by cholestasis. However, it is well known that the potentially cytotoxic bile components could also influence other organs apart from the liver [7, 57]. Kidneys are among the organs significantly influenced by cholestasis [7, 25]. Cholestasis-induced renal injury is known as CN [23, 25]. There is no specific pharmacologic option against CN to date. The current study found that sildenafil administration could significantly protect renal tissue in cholestatic rats. The effect of sildenafil on oxidative stress and its associated complications and its ability to modulate the inflammatory response seem to play an essential role in its nephroprotective mechanisms.

Several mechanisms have been proposed for CN, with oxidative stress being identified as one the fundamental mechanisms [19, 20, 58]. It is well known that supraphysiological concentrations of bile acids could induce oxidative stress in various tissues of cholestatic models, including the brain, heart, lungs, liver, reproductive organs, blood cells, and kidneys [17, 18, 21, 41, 42, 59-65]. The mechanisms of oxidative stress induction in these tissues include the damage of basic cellular antioxidant defense systems (e.g., depletion of cellular GSH reservoirs and defect of antioxidant enzymes) and increased intracellular ROS formation (e.g., increase in mitochondria-originated ROS) [18, 41, 60, 61, 65]. In this study, a significant increase in biomarkers of oxidative stress along with the suppression of renal antioxidant enzyme activity (SOD, CAT, GR, and GPx) was evident in the BDL model of cholestasis (Figs. 4 and 5). On the other hand, we found that sildenafil administration (5, 10, and 20 mg/kg) significantly decreased oxidative stress biomarkers in the renal tissue of cholestatic rats (Fig. 4). The activity of antioxidant enzymes was also significantly higher in the kidneys of cholestatic animals treated with sildenafil (Fig. 5). Previous studies have demonstrated that sildenafil provided nephroprotective properties by modulating kidney oxidative stress [33, 66-68]. For instance, in the cyclosporine A-induced nephrotoxicity model, sildenafil exhibited protective effects by decreasing serum creatinine and urea levels, reducing oxidative stress markers, and enhancing renal antioxidant enzyme activity [69]. In an animal model of chronic kidney disease (CKD), sildenafil improved renal function markers, significantly decreased oxidative stress, and reduced renal histopathological damage [30]. The effect of sildenafil on renal tissue histopathological alterations has been repeatedly mentioned in various experimental models of renal injury [66, 70, 71]. It has been well documented that sildenafil could significantly decrease tissue fibrosis, glomerular lesions, and interstitial inflammation [66, 70, 71]. The effect of sildenafil on oxidative stress and inflammatory response seems to play a significant role in its nephroprotective activity and prevention of renal tissue histopathological changes [66, 70, 71]. These data indicate that the effect of sildenafil on oxidative stress and its associated complications plays a fundamental role in its nephroprotective properties.

At the molecular level, the effects of sildenafil on oxidative stress in biological systems could be mediated through several mechanisms. Sildenafil is a phosphodiesterase 5 enzyme (PD5) inhibitor. Hence, this drug can increase the cellular cyclic GMP (cGMP) levels [72]. It is well known that an increased level of cGMP enhances the activity of protein kinase G (PKG), which it turn can activate pathways that decrease the production of ROS and improve the antioxidant defense system [72-74]. PKG also suppresses the activity of pro-oxidant enzymes and decreases oxidative damage [73]. The regulation of mitochondrial ROS by sildenafil is another interesting mechanism by which this drug can mitigate oxidative stress [75, 76]. It seems that sildenafil could influence mitochondrial oxidative stress [77]. Hence, regulation of mitochondrial function by sildenafil might help protect cells from oxidative damage.

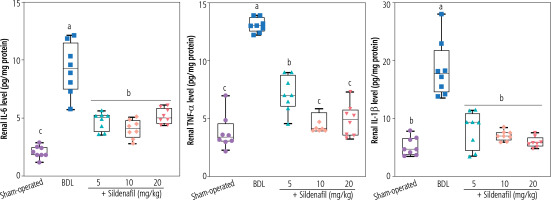

Another primary mechanism by which sildenafil mediates its nephroprotective properties seems to be mediated through the effects of this drug on inflammatory responses. In previous studies, sildenafil downregulated the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β [78, 79]. Mechanistically, the inhibitory effects of sildenafil on NF-kB signaling play a central role in its anti-inflammatory properties [78, 79]. Sildenafil significantly suppressed the production of proinflammatory cytokines by suppressing NF-kB signaling in various experimental models [78, 79]. There is also a connection between inflammatory response and oxidative stress. It is well known that inflammation is closely linked to oxidative stress as pro-inflammatory mediators often stimulate the production of ROS [80]. Moreover, the enzyme myeloperoxidase (MPO), primarily active in inflammatory cells such as neutrophils, could be responsible for ROS formation and oxidative stress [81]. It has been found that sildenafil could decrease MPO activity in previous experimental models of inflammatory diseases [82]. In the current study, we found that sildenafil could significantly suppress the level of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β) in the kidneys of cholestatic animals (Fig. 7). These data indicate that the effect of sildenafil on the inflammatory response could play an essential role in its nephroprotective mechanisms observed in this investigation (Fig. 8). It should be noted that the effect of sildenafil on the inflammatory response of renal tissue was not dose-dependent in the current study.

Fig. 7

Renal tissue level of pro-inflammatory cytokines in bile duct ligation (BDL) model of cholestasis. Data are given as box and whiskers (min to max) for n = 8 rats/group. Data sets with different alphabetical superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05)

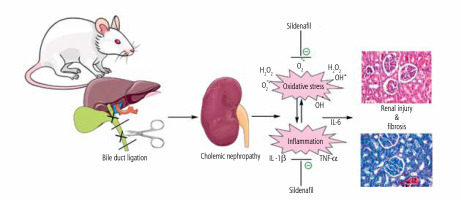

Fig. 8

Schematic representation of nephroprotective properties of sildenafil in cholestasis-associated cholemic nephropathy. The effects of sildenafil on oxidative stress biomarkers and the inflammatory response seem to play an essential role in its nephroprotective properties

Enhancing nitric oxide (NO) signaling is a central pathway by which sildenafil exerts its nephroprotective effects. It has been well documented that by inhibiting phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE-5), increasing cGMP levels, and consequently potentiating NO-mediated vasodilation, sildenafil improves renal blood flow and mitigates ischemic renal injury [83]. Additionally, sildenafil has been shown to attenuate oxidative stress by reducing the production of ROS and enhancing antioxidant defenses, such as SOD and GPx activities [33, 66-68]. Furthermore, sildenafil modulates inflammatory pathways by suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interleukin 6 (IL-6), while promoting anti-inflammatory mediators [83]. These combined effects – enhanced NO signaling, oxidative stress reduction, and anti-inflammatory action – collectively contribute to the nephroprotective properties of sildenafil, making it a promising therapeutic agent for renal pathologies.

Excitingly, several clinical trials have explored the nephroprotective properties of sildenafil. In these studies, sildenafil provided renoprotection in patients undergoing nephrectomy, those with postcardiac surgery-induced acute kidney injury, and individuals with valvular heart disease-related renal impairment [34-37]. Additionally, sildenafil demonstrated promising effects in patients with pulmonary hypertension, significantly decreasing the rate of renal failure [84]. In all these clinical trials, treatment with sildenafil significantly improved the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Sildenafil also significantly decreased serum levels of BUN and Cr, which are critical biomarkers of renal impairment. These compelling findings underscore the potential of sildenafil as an effective nephroprotective agent in clinical settings, highlighting its promise in enhancing kidney function and improving patient outcomes in various renal diseases. It is worth noting here that our findings indicate that the nephroprotective effects of sildenafil were not significantly dose-dependent within the tested range. This observation implies that lower doses of sildenafil may effectively provide renal protection while minimizing the risk of adverse drug reactions. Further studies are warranted to determine the optimal dosing regimen that balances efficacy and safety, which could have significant clinical implications for managing renal diseases.

In conclusion, the data obtained from this study identify sildenafil as a potential protective agent against cholestasis-associated CN. The effect of sildenafil on oxidative stress biomarkers and its ability to mitigate the inflammatory response seem to play a fundamental role in its renoprotective effects. Recent clinical studies have demonstrated that sildenafil could provide nephroprotective effects [31, 84]. Therefore, this drug might readily enter clinical trials to investigate its renoprotective properties in cholestatic patients. Thus, further studies are warranted to investigate the nephroprotective properties of sildenafil in clinical settings.

This study also had some limitations. One limitation is using an animal model, which may not fully represent the complexity of human pathophysiology; therefore, caution should be exercised when extrapolating these findings to clinical scenarios. Additionally, the long-term effects of sildenafil in the context of cholestasis were not explored in our study, which represents an important area for future research. Further investigations are warranted to assess the chronic impact and safety profile of sildenafil in cholestatic conditions, which would provide more comprehensive insights into its potential therapeutic applications in humans.