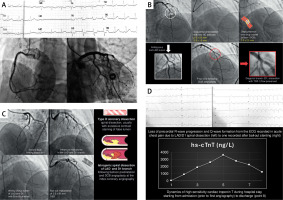

A 58-year-old female patient presented to the Emergency Department with chest pain that began 90 min before admission. A 12-lead electrocardiogram revealed ST-segment elevation in the inferior leads with reciprocal horizontal ST-segment depressions in the anterior leads, as shown in upper right corner of Panel A (Figure 1). She was an active smoker (38-pack years) and had a history of arterial hypertension, for which she was taking an ACE inhibitor and a β-blocker. The working diagnosis of inferoposterior ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) was made. The patient was loaded with dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT; ASA + ticagrelor) with i.v. administration of 5,000 IU of unfractionated heparin. Coronary angiography via the right transradial approach was performed, showing a patent right coronary artery (RCA) with normal left main stem and circumflex branch (Figure 1 A). However, an ambiguous lesion with borderline stenosis was identified in the middle segment of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery in the zone of the strong diagonal branch (D1) take-off. Due to ambiguous and unclear clinical presentation, a left ventriculography was performed, showing no regional contractile dysfunction resembling Takotsubo syndrome (TTS). The operator ultimately presumed this lesion to be of atherosclerotic origin and decided to perform an intervention. A primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) involved sequential predilatation using semi-compliant balloons (2.0 × 20 mm and 2.5 × 15 mm), followed by treatment with a 2.5 × 25 mm paclitaxel drug-coated balloon (DCB) inflated to nominal pressures of 6–8 atm. TIMI-3 flow was achieved in the LAD and D1 branch, although residual dissection appeared to persist in the D1 branch (Figure 1 B). Approximately 90 min later, the patient reported refractory chest pain and was promptly returned to the catheterization laboratory. Anticipating a post-procedural complication, an upfront 7F transfemoral approach was used with a 7F EBU 4 catheter. Angiography revealed a type D spiral dissection affecting both the LAD and D1 branch, almost completely obstructing distal flow. Simultaneous wiring of the LAD and D1 was performed with some difficulty in entering the true lumen. Eventually, a 2.5 × 50 mm sirolimus drug-eluting stent (DES) was deployed from the distal to the proximal LAD, achieving TIMI-3 flow and full visualization of the periphery (Figure 1 C). It is worth noting that from ECG recorded during active chest pain prior to the second angiography and the one recorded after stenting due to spiral dissection, the patient had developed Q-waves in precordial leads and lost normal R-wave progression, thus suggesting irreversible damage to the anterolateral left ventricle (Figure 1 D). This was also accompanied with a significant troponin rise during and after the onset of spiral dissection (Figure 1 D). Finally, transthoracic echocardiography following the second intervention revealed mildly reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (43%) with akinesia of the anteroseptal and apicolateral wall, and preserved RV function.

Figure 1

A – An admission 12-lead ECG suggesting inferoposterior ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) while subsequent index coronary angiography showed patent right coronary artery, LM, and circumflex artery. B – Coronary angiography revealed an ambiguous lesion in the middle segment of left anterior descending (LAD) artery that was adjudicated by the operator as the atherosclerotic culprit lesion for the acute coronary syndrome. This lesion was predilated with two semi-compliant balloons and finally treated with a drug-coated balloon (DCB) while non-flow-limiting dissection in the D1 branch remained following DCB angioplasty. C – Second coronary angiography was performed due to patients’ persistent chest pain showing a type D spiral dissection of LAD and D1 branch likely caused by the iatrogenic vessel injury during previous predilatations and DCB angioplasty. The spiral dissection was handled by bailout stenting and implantation of a long 2.50 × 50 mm drug-eluting stent covering the proximal and distal LAD. D – Severely flow-limiting spiral dissection of LAD and D1 branch caused significant infarction and myocardial necrosis as evident in the dynamic changes of the 12-lead ECG and accompanying dynamics of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T

There are several caveats to this challenging case. It is unclear what caused inferoposterior ST segment changes on the admission ECG, and there is a possibility that this was a transient phenomenon due to vasospasm, since no obstructive disease or lesions were found in coronary arteries supplying this territory. Regarding the ambiguous LAD lesion, a type 3 spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) could be considered in the differential diagnosis due to a possibility that it was an image of intramural hematoma, while TTS should also be suspected and excluded by left ventriculography at the index angiography, such as in our case. It is also possible that this was a non-obstructive “bystander” atherosclerotic lesion not related to the acute event. The learning point is that ambiguous or even non-significant lesions in the setting of ACS should be further interrogated with intravascular imaging (intravascular ultrasound – IVUS or optical computed tomography – OCT), and this was a missed opportunity. On the other hand, use of IVUS and OCT should be judicious in the SCAD setting, since that might propagate dissection and induce severe spasm. Similarly, non-critical lesions with TIMI-3 flow and absence of ongoing ischemia should be treated with medical therapy, and deferred functional testing using fractional flow reserve might be considered.

While DCBs are a legitimate treatment option for de novo coronary artery lesions [1, 2], this case highlights their potentially severe complications. Optimal lesion preparation is a critical step before DCB treatment. Intravascular imaging (IVI) such as with IVUS or OCT is warranted after lesion predilatation and prior to DCB application if there is a suspicion of non-benign dissection and/or residual stenosis. If an acceptable angiographic result is present after lesion preparation, satisfying three criteria – TIMI-3 flow, no flow-limiting dissection/or only type A/B dissections, and residual stenosis ≤ 30% – then DCB therapy may be pursued, although some operators are comfortable not intervening on residual non-flow-limiting type C dissections and post-interventional stenoses greater than 30%. The final angiography following DCB should be analyzed carefully as well, since TIMI-3 flow is only one of the determinants of a good result, but we need to be aware of potential dissection flaps and residual stenosis. As an important consequence, the described sequence of events in our case ultimately caused significant damage to the anterior and apicolateral wall, and the patient was discharged with heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF). Equally relevant as a teaching point, intravascular imaging (IVUS or OCT) should be considered to evaluate ambiguous de novo lesions and also post-DCB results to detect potentially important residual dissections [3]. It is likely that these lesions can be treated conservatively if there is preserved flow, no ongoing ischemia, no dynamic ECG changes, and no other culprit lesions identified. Finally, bailout stenting should be performed in cases of flow-limiting dissection to prevent further propagation. Gitto et al. reported a 29.3% rate of residual dissections after DCB angioplasty in de novo LAD lesions, with 30.2% requiring bailout stenting [4]. In this case, undetected residual dissection, in the zone of LAD/D1 bifurcation, was likely caused by balloon predilatations and DCB angioplasty and later propagated spirally, manifesting in chest pain, dynamic ECG changes, and finally significantly complicating the clinical course.