Introduction

Head and neck cancer remains the sixth most common malignancy worldwide, with an estimated annual incidence of approximately 800,000 new cases [1]. Surgical resection of these tumours frequently results in substantial functional impairments, necessitating advanced reconstructive strategies [2]. Despite significant progress in surgical techniques, data on innovative reconstructive approaches aimed at restoring essential functions and addressing aesthetic concerns in patients with head and neck cancer remain limited [3, 4].

Among the available options, free tissue transfer with microvascular anastomosis has emerged as a highly effective method, enabling extensive tumour resections while preserving an acceptable quality of life [5]. The versatility of this technique, particularly its ability to accommodate flap modifications tailored to individual defect geometries, makes it well suited for addressing the complex challenges associated with aggressive oncologic surgery [6].

While venous coupler devices have gained widespread acceptance in microsurgical anastomoses –including head and neck reconstruction – their arterial counterparts have posed greater technical challenges [7]. Variations in arterial wall histology and the difficulty in selecting appropriately sized couplers have led many surgeons to continue relying on traditional hand-sewn techniques for arterial anastomoses [8]. However, growing evidence suggests that arterial coupler anastomosis is a promising and viable alternative in head and neck reconstruction [9, 10]. Reported benefits include reduced operative time and a lower incidence of flap failure, positioning this method as a valuable advancement in microsurgical practice [11–13].

In this study, we report our five-year experience with the simultaneous use of arterial and venous coupler anastomoses in microvascular reconstruction for head and neck cancer patients. Our aim was to prove that simultaneous use of both arterial and venous coupler anastomosis serves as a feasible approach and can be successfully trained by a microsurgeon. This retrospective analysis offers robust evidence supporting the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of this approach in a large patient cohort. Our findings clearly demonstrate that simultaneous arterial and venous coupler anastomosis is a reliable and time-efficient strategy that contributes to reduced rates of post-surgical complications while also exhibiting a satisfactory and reproducible learning curve.

To our knowledge, this is the first study conducted on such a large patient cohort – operated on entirely by a single microsurgeon – assessing the routine application of arterial coupler anastomosis in head and neck reconstruction.

Material and methods

Subjects

This retrospective study included 127 patients who underwent free flap reconstruction for head and neck cancer between January 2019 and January 2024. Eligible patients had tumour resection (with or without lymph node dissection) followed by microsurgical reconstruction using couplers. Data were collected from medical records using patient and hospital identifiers. All procedures were performed under general anaesthesia, including tumour resection, flap harvest, vessel preparation, and microvascular anastomosis. Evaluated variables included patient-related factors (age, gender, smoking, digastric muscle, atherosclerosis, radiotherapy – RTH, chemotherapy – CHTH), tumour characteristics (location, histology), and surgical parameters (flap type, coupler size, vessel type). Postoperative complications and potential risk factors for flap necrosis were analysed. Operative time was defined/measured from the first incision to final closure.

Microsurgical coupler device

The Synovis Microvascular Anastomotic Coupler Device (Synovis Micro Companies Alliance, Inc., Alabama, USA) was employed to perform both venous and arterial anastomoses. No device-related complications were observed in any of the cases.

Post-surgical flap assessment

During the immediate postoperative period, flaps were monitored daily for five consecutive days. In addition to an initial assessment on the day of surgery (12:00 AM), evaluations were conducted every six hours (6:00 AM, 12:00 PM, 6:00 PM, and 12:00 AM) using a standardized flap chart (Table 1). Monitored features included flap colour, oedema, and vascular flow, each scored 1–3. Colour: 1 = blue, 2 = pale, 3 = pink; Oedema: 1 = hard, 2 = swollen, 3 = flabby; Vascular flow: 1 = no flow, 2 = doubtful, 3 = good flow. A total score ≤ 6 indicated flap abnormality; > 6 confirmed a healthy flap. Blood flow was assessed with an 8 MHz Doppler device (Sonomed®, MD4, Warsaw, Poland). All patients received 40 mg of heparin sodium and were maintained with crystalloid fluids to ensure hemodynamic stability. Other postoperative complications (oedema, infection, hematoma) were assessed three times daily for the first seven days and at monthly follow-ups during the first postoperative year. These were recorded using a binary scale (1 = complication present, 0 = normal flap).

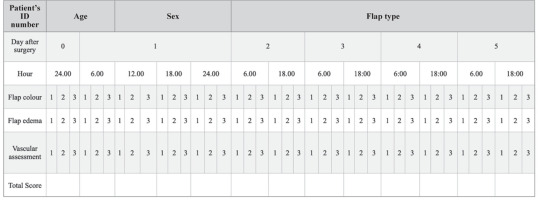

Table 1

Flap assessment chart used to evaluate flap viability during the postoperative period

|

[i] Three clinical parameters – colour, oedema, and vascularity – were each scored on a scale 1–3. Colour: 1 = blue, 2 = pale, 3 = pink. Oedema: 1 = firm, 2 = swollen, 3 = flabby. Vascularity/Vascular flow: 1 = absent/no flow, 2 = questionable/doubtful flow, 3 = good flow. A cumulative score ≤ 6 indicated flap compromise/abnormality, while a score > 6 was consistent with a viable flap.

Surgical time analysis and learning curve assessment

The total surgical time was measured from the initial incision to the completion of the procedure. Learning curve assessment was subsequently conducted based on these time measurements to evaluate the progression of surgical efficiency over time. Cumulative sum (CUSUM) analysis was performed to assess the surgical learning curve. Cumulative sum analysis serves as a sequential statistical technique detecting small shifts in data over time. In medicine, it is frequently used to evaluate procedural learning curves by identifying the point at which performance stabilizes. In this study, CUSUM analysis was performed to evaluate changes in surgical time across consecutive cases, organized chronologically by operation date. The cumulative sum value for the first case (CUSUM1) was calculated as the difference between the surgical time of the first case (OT1) and the mean surgical time (OTmean) across all cases, using the formula: CUSUM1 = OT1 – OTmean. For each subsequent case, the CUSUM value (CUSUMn) was computed as the sum of the previous CUSUM value (CUSUMn) and the difference between the surgical time of the current case (OTn) and the overall mean surgical time: CUSUMn = (OTn – OTmean) + CUSUMn–1. This process was repeated sequentially for all cases. The resulting CUSUM values were plotted to produce a learning curve. A rising slope in the CUSUM plot indicates longer-than-average surgical times (early learning phase), while a downward slope suggests improving efficiency. A plateau indicates consistent performance. Subsequently, the breakpoint in the learning curve was determined retrospectively using piecewise linear regression. A segmented (broken-line) model was applied to identify the case numbers corresponding to transitions between the initial learning phase, performance improvement phase, and the plateau phase.

Statistical analyses

The age data were reported as mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD), with all data presented in tabular form. The χ2 test was applied to compare qualitative variables between groups. The Wilcoxon test was used to compare quantitative variables with distributions that deviated significantly from normality. Statistical analysis was performed using R in the RStudio Software (RStudio Version 1.4.1564 on MacOS 10.15.7). Results were considered statistically significant with p-values < 0.05.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population

A total of 127 patients were included in the study. Women comprised 40.2% (n = 51) of the cohort, while men accounted for 59.8% (n = 76). The mean age of the patients was 61.96 ±11.32 years (mean ± SD). Diabetes mellitus was present in 15.7% (n = 20) of participants, and 25.4% (n = 32) had atherosclerosis. A history of smoking was reported by 58.3% (n = 74). Preoperative RTH was administered in 11.8% (n = 15) of cases, while postoperative RTH was given to the majority of patients (64.4%, n = 82). Preoperative CHTH was used in 6.3% (n = 8), a proportion comparable to that of patients receiving postoperative CHTH (8.7%, n = 11) (Table 2).

Table 2

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population

Comprehensive analysis of tumour location and histopathological classification

The most common tumour location identified was the tongue, accounting for 27.6% (35) of cases, which was comparable to the percentage of tumours located in the floor of the mouth – 24.4% (31). The third most common tumour location in the study group was the cheek mucosa, representing 10.2% (13) of cases (Figure 1 A). Regarding tumour histology, squamous cell carcinoma was the most common diagnosis, confirmed in 85% (108) of patients. The second most common cancer type identified was basal cell carcinoma, accounting for 3.1% (4) of cases, followed by adenoid cystic carcinoma, which was the third most common type, representing 2.4% (3) of cases. Detailed data on tumour histology are presented in Figure 1 B.

Figure 1

Distribution of tumour location and histologic subtype among patients undergoing head and neck microvascular reconstruction. Bar graph depicting the anatomical location of primary tumours. The most common tumour sites were the tongue, floor of the mouth, and cheek mucosa (A), bar graph showing the histologic classification of tumours (B)

Squamous cell carcinoma was the predominant histologic type, followed by basal cell carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma. Other histologic variants were infrequent.

Assessment of flap type, arterial and venous recipient vessels, and coupler sizes used

The analysis of flap types demonstrated that the radial forearm free flap was the most frequently employed technique for microsurgical reconstruction, used in 55.6% (n = 70) of cases. This was followed by the anterolateral thigh flap in 34.9% (n = 44) and the free fibula flap in 9.5% (n = 12). Evaluation of arterial recipient vessels revealed that the facial artery was the predominant choice, utilized in 87.4% (n = 111) of cases. The superior thyroid artery was used in 11.0% (n = 14), while both the transverse cervical and pharyngeal arteries were each used in a single case (0.8%). Regarding arterial coupler sizes, size 3.0 was the most commonly selected (50.4%, n = 64), followed by size 2.5 (40.9%, n = 52). Smaller proportions of patients received size 2.0 (3.9%, n = 5) or size 3.5 (4.7%, n = 6) couplers. For venous anastomoses, the facial vein was the most frequently utilized recipient vessel (n = 111), followed by the superior thyroid vein (n = 17). Venous coupler sizes most commonly used were 3.5 and 3.0. Notably, two venous anastomoses were performed in 27.6% of cases (n = 35). Comprehensive data on vessel types and coupler sizes, along with their respective frequencies, are presented in Table 3. An exemplary intraoperative image illustrating simultaneous venous and arterial coupler anastomoses is shown in Figure 2.

Table 3

Assessment of flap type, vessel type, and coupler size

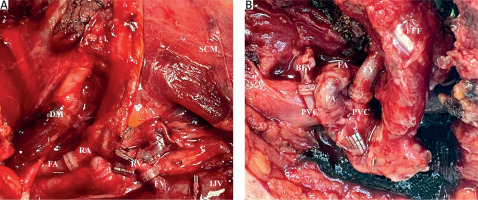

Figure 2

Intra-operative images illustrating the simultaneous use of arterial and venous coupler anastomoses in head and neck microvascular reconstruction. Radial forearm free flap reconstruction showing arterial anastomosis between the radial artery and facial artery, and venous anastomosis between the radial vein and facial vein, both performed using microvascular couplers (A), free fibula flap reconstruction demonstrating arterial anastomosis between the peroneal artery and facial artery, along with venous anastomoses between the peroneal venae comitantes and recipient veins, all completed with coupler devices (B)

BFV – branch of the facial vein, DM – digastric muscle, FA – facial artery, FFF – free fibula flap, FY – facial vein branch, FV – facial vein, IJV – internal jugular vein, PA – peroneal artery, PVC – peroneal venae comitantes, RA – radial artery, RV – radial vein, SCM – sternocleidomastoid muscle

Surgical training assessment

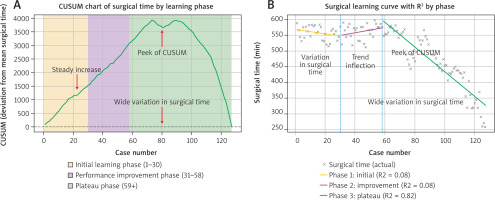

To evaluate the progression of surgical proficiency over time, we employed both CUSUM analysis and piecewise linear regression. The cumulative sum chart plotted cumulative deviations from the mean surgical time (506.8 ±82.1 minutes) and revealed a distinct learning curve trajectory: an initial upward slope indicating prolonged operative times during early cases, a peak around case 76, and a subsequent sharp downward trend reflecting consistent performance improvement. Based on inflection points in the CUSUM curve, we defined three phases: Initial Learning Phase (cases 1–30), Performance Improvement Phase (cases 31–58), and Plateau Phase (cases 59 onward) (Figure 3 A). To validate this phase-based structure, we applied piecewise linear regression to actual surgical times. The model confirmed a limited trend in the first two phases, with low explanatory power (R2 = 0.08 for both Phase 1 and Phase 2), indicating high variability in surgical duration. In contrast, Phase 3 demonstrated a strong linear decrease in operative time (R2 = 0.82), consistent with skill acquisition and standardization of the technique (Figure 3 B). The comparative analysis of the learning phases did not reveal any significant statistical differences (Table 4).

Figure 3

Assessment of the surgical learning curve for arterial and venous coupler anastomoses in head and neck microvascular reconstruction. Cumulative sum chart of surgical time plotted against case number, illustrating three learning phases: Initial Learning Phase (cases 1–30), Performance Improvement Phase (cases 31–58), and Plateau Phase (cases 59 onward). Shaded areas denote the respective learning intervals. The chart demonstrates an initial upward trend indicating longer surgical times, followed by a peak and subsequent decline, reflecting improved efficiency and skill acquisition (A), piecewise linear regression model applied to actual surgical times across the same three phases (B)

Phase 1 (orange) and Phase 2 (purple) show minimal correlation with surgical duration (R2 = 0.08), indicating high variability. In contrast, Phase 3 (green) demonstrates a strong linear decline in operative time (R2 = 0.82), consistent with procedural standardization and stable technical proficiency.

Table 4

Comparison of the three learning phases

Postoperative flap evaluation

Flap failure occurred in four cases. No significant correlation was found between flap necrosis and patient-related factors (gender, age, DM2, smoking, atherosclerosis) or surgical variables (artery type, vein type, venous coupler size). The only significant association was between flap failure and the use of a 3.5 mm arterial coupler (p < 0.049). Tumour characteristics (histopathology, location) and pre-/postoperative CHTH or RTH had no significant impact. Detailed statistical data are presented in Table 5 and the Supplementary Material. No intraoperative complications were observed during the study.

Table 5

Necrotic flap analysis

Necrotic flap assessment

Postoperative complication analysis revealed flap necrosis in only 3.1% of cases (n = 4). Detailed evaluation of these cases demonstrated that oedema was present in all patients, with no evidence of infection or bleeding. All necrotic flaps required surgical removal, during which intra-operative findings consistently revealed venous anastomosis failure due to thrombus formation. In all cases, the facial vein was used for venous anastomosis. Notably, the facial artery was consistently used across all cases and during surgery the arterial coupler anastomosis was confirmed to be patent. A comprehensive summary of flap failure cases and all assessed variables is presented in Table 5.

Discussion

Surgical management remains the most effective and widely preferred approach for patients with head and neck cancer [14]. Despite significant advancements in minimally invasive surgical techniques, the number of patients presenting with advanced head and neck malignancies continues to rise, necessitating extensive resections [15]. As a result, microvascular free flap reconstruction has become the gold standard for addressing complex defects in this patient population, with the dual goal of restoring both form and function [16, 17]. Although the rich vascular network in the head and neck region facilitates successful free flap transfer, the risk of flap necrosis – while relatively low – remains a concern [18, 19].

Traditionally, microvascular anastomoses are performed via hand-sewn techniques. However, anastomotic coupling systems have emerged to simplify these technically demanding and time-intensive procedures [20, 21]. Venous couplers have been already well-documented as a feasible and effective approach in head and neck reconstruction [22–24]. Nevertheless, the use of arterial coupler anastomosis remains limited [25].

In this study, we present comprehensive findings on the surgical learning curve associated with the simultaneous use of arterial and venous couplers for microvascular anastomoses in patients undergoing reconstruction for head and neck cancer. Our results highlight the feasibility, safety, and efficiency of arterial coupler application – a technique that remains underused in this anatomical region. Furthermore, by tracking the progression of operative performance over time, we offer robust evidence of microsurgical skill acquisition.

To date, no published studies have examined the learning curve associated with arterial coupler anastomosis in head and neck cancer reconstruction. To objectively assess the progression of surgical proficiency, we employed both CUSUM analysis and piecewise linear regression. The cumulative sum chart revealed a distinct three-phase learning pattern: an initial upward trend in operative time, a peak around case 76, and a subsequent decline reflecting greater efficiency and consistency. Based on these inflection points, we defined the Initial Learning Phase (cases 1–30), Performance Improvement Phase (cases 31–58), and Plateau Phase (cases 59 onward). Piecewise linear regression supported this segmentation, demonstrating low predictive power in the first two phases (R2 = 0.08) and a strong correlation in the third phase (R2 = 0.82), indicative of technical proficiency and procedural standardization. These findings underscore the utility of CUSUM analysis in tracking surgical performance and identifying the threshold – approximately 58 cases – at which independent competence may be achieved.

Although numerous studies have established a correlation between surgical experience and improved outcomes in microvascular head and neck reconstruction, the majority have not involved in vivo human applications of microsurgical couplers. In a study by Pafitanis et al. [26], novice microsurgeons used couplers on a three-layer silastic vessel in an animal model. A total of 60 coupler anastomoses were performed – 40 in Phase 1, 12 in Phase 2, and 8 in Phase 3. On average, 8 (range 6–9) and 4 (range 2–6) repetitions were required in Phases 1 and 2, respectively, to reach expert-level performance. Performance improved by 69% in Phase 1 and 37% in Phase 2 (both p < 0.001). Similarly, Zdolsek et al. compared learning curves for sutured and mechanical microvascular anastomoses in a rat model. Among various techniques – including conventional suture, vascular closure system, and microvascular anastomotic coupler (MAC) – the MAC technique required the least time (13 minutes) and yielded the highest patency rate (95%) [27]. However, these studies did not explore the simultaneous use of arterial and venous couplers in clinical head and neck cancer microsurgery, as presented in our study.

Beyond the learning curve, we analysed clinical and pathological factors influencing flap viability. Although diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, and smoking are known to compromise vascular health [28, 29], no significant correlation with flap failure was observed in our cohort. Likewise, although prior studies by Chang et al. [30] and Pfister et al. [31] have implicated RTH and CHTH in impairing wound healing and vessel patency, our analysis did not reveal any impact of pre- or post-surgical adjuvant therapy on flap viability.

Tumour location and histology are essential in planning resection and reconstruction [32]. Despite the challenges posed by recurrent disease and prior surgical interventions, which may compromise recipient vessels [33, 34], we found no significant association between tumour characteristics, flap type, or anastomotic success.

We also examined vessel selection, known to influence patency [35]. Although the facial artery and vein were most frequently used, no correlation was observed between vessel choice and flap failure. Our data suggest that coupler size – particularly in arterial anastomosis – may play a more pivotal role. Venous discrepancies are generally manageable due to vessel wall compliance, whereas arterial mismatch presents greater difficulty [36, 37]. We observed that choosing a coupler to match the larger vessel, along with adjunctive techniques such as adventitiectomy or longitudinal slitting, improved outcomes. A notable finding was the association between 3.5 mm arterial couplers and flap failure, likely due to mechanical stress impairing blood flow and vessel integrity. While arterial dilation can risk intimal damage, this appears less severe than complications associated with hand-sewn techniques [38]. Therefore, larger studies are needed to confirm these associations.

Undersizing the coupler relative to the vessel was also associated with intraoperative failure. As noted by Pafitanis et al. [7], arterial wall thickness and rigidity can hinder eversion onto the coupler. Despite these challenges, our findings confirm that arterial coupler anastomosis can be effectively implemented in head and neck reconstruction.

A major limitation of this study is the low incidence of flap failures, which may reduce statistical power despite an adequate sample size. Most failures were likely attributable to poor vessel quality or insufficient venous drainage. While our statistical analyses did not yield significant predictors of failure, the overall data strongly support the safety and effectiveness of coupling techniques. Cumulative sum analysis, while valuable for identifying performance trends, lacks the capacity to account for confounding factors such as case complexity, trainee involvement, or concurrent procedures.

Conclusions

Nevertheless, this study is the first to document a successful learning curve for the concurrent use of arterial and venous couplers in head and neck cancer reconstruction. Our findings reinforce the coupler technique as a reliable, efficient alternative to traditional hand suturing, with significant implications for improving microsurgical outcomes in complex oncologic cases.