Introduction

Chronic liver disease represents a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide and a significant economic burden for the healthcare system. Slovakia ranks at the top of the prevalence of liver cirrhosis in the world [1]. Moreover, liver diseases are the leading cause of death in the age group of 25-50 years [2]. The dramatic increase in the number of patients with liver diseases in our region is disproportionate to the current hepatology network and workforce, prompting the search for ways out. Telehepatology may represent a solution for delivering high-quality, cost-effective, and patient-oriented medicine with a limited need for additional resources.

The COVID-19 pandemic has catalysed the implementation of telemedicine (TM) in the field of hepatology and liver transplantation [3, 4]. This crisis has created an opportunity to explore the advantages and limitations of TM in real-life clinical practice [5]. In Slovakia, the implementation of social distancing policies has resulted in skewed specialized/tertiary care. Most planned and on-demand outpatient services have been postponed, acute hospitalizations have been redirected to lower-rank institutions and liver transplantations have been deferred, except for urgent indications. According to our registry study, it significantly increased the non-COVID-related mortality rate [6] and introduced a potential new predictor of outcome – time-to-tertiary care [7]. These findings have become a driving force behind the search for new solutions within the paralyzed healthcare system. In cooperation with Goldmann Systems, we have initiated a telemedicine prospective open-label feasibility trial based on the Telemon system; we aimed to investigate the potential of the new branch of medicine that is telehealth, in terms of uptake and adherence by patients and of metrics reflecting the outcome. We designed this project following our previous experience [8].

In this feasibility study, we retrospectively evaluated signals from three domains: the patients’ uptake and technical grasp of TM; data flow and fidelity; and their first-order-granularity medical usability.

Material and methods

Study design and participants

We conducted a prospective open-label trial to implement TM for patients with liver cirrhosis and post-liver transplantation and retrospectively analysed the implementation process. We included patients aged 18 and older with liver cirrhosis enrolled in the RH7 Cirrhosis Registry and those who had undergone liver transplantation under the care of the outpatient and inpatient tertiary care liver clinic (Division of Hepatology, Gastroenterology, and Liver Transplant, II Internal Medicine Department, F.D. Roosevelt University Hospital). We excluded patients who declined study participation and those who were unable to familiarize themselves with TM technology. This study was supported by the project “Telemedicine as a tool for effective management of the healthcare system affected by the pandemic caused by the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)”, ITMS 2014+: 313011ATK9, supported by the Operational Programme Integrated Infrastructure funded by the European Regional Development Fund. The protocol was approved by the Institutions Review Board at F.D. Roosevelt University Hospital of Banska Bystrica (FDR UGH Ethics Committee, 20/2021 and 17/2023). All patients provided written informed consent before participation.

Patients who decided to participate and met the inclusion and exclusion criteria received a TM package. On the day of discharge or during their outpatient department visit, they underwent an initial interview with the TM coordinator. During this interview, patients learned how to use the TM package and the frequency of measurements required. The TM package contained a mobile hub, digital automatic blood pressure monitor (G.LAB, MD4781), non-contact infrared thermometer (Rycom, JXB-182B), glucometer (FORA Diamond MINI), and body composition scale (Medical monitor, W62) in TM1 and a mobile hub, digital automatic blood pressure monitor (G.LAB, MD4781), non-contact infrared thermometer (Berrcom, JXB-182B), glucometer (FORA Diamond MINI), body composition scale (Xiaomi), ECG monitor (Heal Force), fingertip pulse oximeter (ChoiceNMed Oxywatch) and spirometer (Contec, SP80B) in TM2. All listed devices were provided to all included patients in one TM package. Subsequently, technical support in cooperation with patients verified the functionality of the devices and the connection and data transition to the mobile hub and online central database. Threshold values were configured for each patient for every measurement. Data were only collected in the pilot phase (TM1); in the subsequent phase (TM2), data were collected simultaneously and implemented in health care. In the event that the measured values exceeded the predetermined thresholds, the physician received a notification via email. If the physician assessed this alert as relevant, he/she contacted the patient about adjustments to the treatment or the need for further examination by a GP or in the hepatology outpatient clinic. In the course of the study period, patients had access to telephonic technical support. All included patients underwent regular laboratory follow-ups tailored to the severity of their condition and based on clinical recommendations, either at their general practitioner’s clinic or at our hepatology outpatient clinic. Extra outpatient visits for laboratory follow-ups were arranged based on alerts. Telemedicine, including the loan of devices, home monitoring, telephone technical support, and contact by a physician in case of pathological values, was provided to patients free of charge. Laboratory monitoring, outpatient visits, and alert-based teleconsultations were covered by patients’ healthcare insurance.

Data collection

We conducted a retrospective analysis of the medical records of patients discharged from the tertiary care liver department following a visit or hospitalization due to decompensation of liver cirrhosis and liver transplantation. The study was divided into two phases: TM1 (pilot phase), which took place from August 2021 to August 2022, and TM2 (subsequent phase), which took place from September 2022 to October 2023. Patients conducted measurements according to a predefined plan, including blood pressure twice daily (morning and evening), body temperature twice daily (morning and evening), body weight once daily (morning), glycemia three times daily (morning fasting, 1 hour after the main meal, before bedtime), EKG once daily (morning), spirometry once daily (morning), and oximetry once daily (morning). Recorded values were collected in a mobile hub and subsequently transmitted to an online central database. We also recorded basic data about participants, MELD, grade of hepatic encephalopathy, Liver Frailty Index (LFI), acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) in patients with liver cirrhosis, the occurrence of new onset of arterial hypertension and diabetes after liver transplantation, mortality, and hospitalization rate. The healthcare provided based on alerts received from the central database was consistently documented and retrospectively evaluated. The collected data were recorded in a confidential electronic case report form, the electronic database was managed only by the study’s main researchers, and data were de-identified before analysis.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome of this study was the assessment of the feasibility and fidelity of TM in the advanced liver unit. This was evaluated by analysing the number of shortened, averted, and timely resolved hospitalizations and assessing the adherence to TM based on a comparison of planned versus actual measurements and the reasons for any termination. The secondary outcome of this study was the evaluation of the difference in shortened, averted, and timely resolved hospitalizations and adherence between the pilot and subsequent phases.

In the realm of statistical analysis, we succinctly summarized categorical variables through frequencies and percentages, providing a comprehensive distribution overview. For normally distributed continuous variables, we applied standard procedures, including the t-test (or ANOVA if applicable), to compare means and measure variability. Conversely, variables lacking a normal distribution were presented as the median and interquartile range. Appropriate statistical methods were employed for categorical variables, while robust methods such as the Mann-Whitney U test were utilized for continuous variables that did not follow a normal distribution. The data transfer speed methodology involved identifying all clinical measurements and setting time intervals for transferring values (30 seconds to over 24 hours). Measurements were categorized based on these intervals using timestamps. Calculating the data transfer ratio in each interval offered an efficiency overview; the emphasis was on evaluating the 2-minute threshold. All analyses were executed in Jupyter Notebook (v6.4.8) via Anaconda virtual env, ensuring the robustness of our statistical evaluations.

Results

From August 2021 to October 2023, a total of 95 patients were included in the study (58% men and 42% women). The age analysis showed that the modal age of patients was 58 years.

In the pilot phase of the study (TM1), we enrolled 24 patients. The mean age was 53 years; 67% were men, 63% had a history of liver cirrhosis, 25% had undergone liver transplantation, and 12% had various other internal medicine diagnoses. In patients with liver cirrhosis, the mean MELD at admission was 18.8 ±7.9 (signifying a decompensated state), the mean Liver Frailty Index (LFI) was 4.1 ±1.1, and 8% met the criteria for ACLF. Twenty-one percent of cirrhotic patients had hepatic encephalopathy (HE) grade 1, and 4% grade 2 according to the West Haven classification. The aetiology of liver cirrhosis in this cohort was alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) in 46%, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) in 4%, autoimmune liver disease in 13%, viral hepatitis and Wilson disease in 4%, and cryptogenic cirrhosis in 29% (Table 1).

Table 1

Baseline characteristics (TM1)

[i] ALD – alcohol associated liver disease, MASLD – metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, AIH – autoimmune hepatitis, PSC – primary sclerosing cholangitis, PBC – primary biliary cholangitis, HE – hepatic encephalopathy, LFI – Liver Frailty Index, MELD – Model for End-Stage Liver Disease, ACLF – acute-on-chronic liver failure

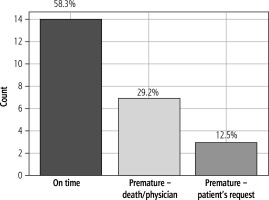

Patients were monitored using TM for an average of 218.6 days; two patients were monitored over 700 days. In the pilot phase, we monitored glucose levels, body temperature, blood pressure, and body weight. The highest average number of recorded values was for blood pressure (257), followed by body temperature (240). The lowest number of measurements was observed for glucose, with an average of 101, and the average number of weight measurements was 149. In the overall comparison of planned and executed measurements, 47% did not fulfil the intended number of measurements. The analysis of the termination of telemedical monitoring in the pilot phase revealed that 58% of patients finished the TM monitoring at the scheduled time, 29% of TM protocols were terminated due to the patient’s death or upon the physician’s recommendation due to a significant deterioration or improvement of health status; and 13% of patients terminated measurements based on their own decision, unrelated to health status.

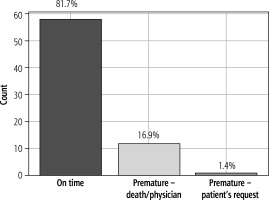

In the subsequent phase (TM2), continuously following the pilot phase (TM1), we enrolled 71 patients. The mean age was 66 years; 52% were men, 48% were women, 56% had a history of liver cirrhosis, and 44% had undergone liver transplantation. In patients with liver cirrhosis, the mean MELD at admission in patients with liver cirrhosis was 19.5 ±6.9, the mean LFI was 3.9 ±0.8, and 24% met the criteria for ACLF. The majority of patients (75%) did not have hepatic encephalopathy; only 13% had hepatic encephalopathy grade 1, and 3% grade 2 according to the West Haven classification. The aetiology of liver cirrhosis in this cohort was ALD in 54%, MASLD in 4%, autoimmune liver disease in 23%, viral hepatitis and Wilson disease in 1%, and cryptogenic cirrhosis in 17% (Table 2). Patients were monitored using TM for an average of 138 days. In the subsequent phase (TM2) besides glucose levels, body temperature, blood pressure, and body weight, we monitored electrocardiography (ECG), oxygen saturation by oximeter, and lung function by spirometry. The highest average number of recorded values was for body temperature (176), followed by blood pressure (173). The average number of measurements for glucose level was 103, while for body weight it was 96. The average number of measurements for lung functions was 84, and for ECG it was 81. The lowest average number of measurements was observed for oximetry, which was 76. The comparative analysis between the planned and executed measurements showed that 18.3% of the measurements did not meet the expected frequency (non-adherence). The analysis of the cessation of TM monitoring during the subsequent phase of the study revealed that the majority of patients (81.7%) successfully concluded monitoring at the designed time. A small fraction (16.9%) discontinued due to death or the physician’s decision, while only 1.4% of patients terminated the process based on their discretion, unrelated to any health complications (Figs. 1 and 2).

Table 2

Baseline characteristics (TM2)

[i] ALD – alcohol associated liver disease, MASLD – metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, AIH – autoimmune hepatitis, PSC – primary sclerosing cholangitis, PBC – primary biliary cholangitis, HE – hepatic encephalopathy, LFI – Liver Frailty Index, MELD – Model for End-Stage Liver Disease, ACLF – acute-on-chronic liver failure

As for the third domain, we evaluated the impact of TM on the hospitalization rate. Out of the total number of participants in the pilot (TM1) phase (24), hospitalization was shortened for 0% of patients, averted for 4.2%, and accelerated (timely hospitalization for development of potentially severe complications) for 8.3%. Subsequently, in the TM2 phase, we focused on patients enrolled, and during this phase, individual alerts were personalized and evaluated by the physician. Out of the total of 71 patients, hospitalization was shortened for 11.3% of patients (1.4% with advanced chronic liver disease [ACLD] vs. 9.9% post-LT, respectively), averted for 14.1% of patients (8.5% vs. 5.6%), and accelerated (timely hospitalized) for 22.5% of patients (5.6% vs. 16.9%).

Finally, we analysed the transfer speed of measured data from the patient to the online central database. Out of the total of 39,711 measurements, 87% of the recorded values were transmitted within 2 minutes, and 96.6% within 24 hours. Thirteen percent of the measured data required more than 2 minutes for transmission, with the greatest delays observed in data coming from the spirometer (43.8%), followed by data from the blood pressure monitor (22.8%).

Discussion

Digital health and telemedicine have become important concepts in the modern healthcare system. The World Health Organization defines digital health as the development and utilization of digital technologies to meet healthcare-related requirements. TM involves the provision of healthcare services remotely through communication exchanges between healthcare providers who seek clinical guidance and support from their counterparts (provider-to-provider TM), or between remote healthcare users and healthcare providers (client-to-provider TM) [9, 10]. The development and availability of technologies have enabled interactive communication (synchronous TM), tracking variable medical parameters with later analysis and interpretation by distant medical professionals (remote monitoring), and further interaction at different times (asynchronous TM) [11]. The World Health Organization has also identified four key components that TM must possess: provide clinical support, overcome geographic barriers, involve various communication technologies, and improve health outcomes [12]. The rapid utilization of digital technologies in the healthcare sector enabled it to fill the healthcare quality gap in three different TM models: teleconsultations, televisits, and telemonitoring [11, 13, 14].

Teleconsultations enhance access to tertiary care for patients in remote areas and enable healthcare providers to collaborate with specialists for patient management. Published articles have documented the effective utilization of teleconsultations in managing hepatitis C, hepatocellular carcinoma, and pre- and post-transplantation care. Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of teleconsultations in managing patients with hepatitis C in rural and underserved areas, comparable to the standard of care, with no significant differences in sustained virologic response rates [15-17]. Teleconsultations have been shown to increase hepatitis C treatment rates [18] and appear to be a cost-effective approach [19, 20]. Moreover, several studies have highlighted promising outcomes in the global efforts to eliminate HCV infection [21]. In the care of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, teleconsultations facilitate effective management through multidisciplinary evaluations conducted in virtual tumour boards [22]. Furthermore, the implementation of teleconsultations in liver transplant programmes can significantly affect the evaluation process by reducing the time from referral to the initial evaluation of liver transplant candidates, particularly among patients with low MELD scores, shortening the listing time [23, 24], and early identification of non-candidates for transplantation before completing the full workup, resulting in cost reduction [25]. Additionally, teleconsultations have the potential to improve care before and after liver transplantation [26].

Televisits represent a direct form of consultations between caregivers and patients, which have proved to be particularly beneficial for patients with chronic liver disease, as well as those before and after liver transplantation [26, 27]. This form of TM has the potential to improve patient care and outcomes through early symptom detection, followed by intervention, education, and support. Increased follow-up through televisits can prevent complications, resulting in higher survival rates, with no significant difference or even reduced readmission rates, and similar or higher patient satisfaction. Several studies have documented increased compliance, a decrease in dropout rates, and lower costs compared to in-person treatment [17, 28-30]. Additionally, televisits have shown promise in managing alcohol-related liver disease, with video consultations being effective in preventing relapses, reducing hospitalization, and improving the quality of life of patients [31].

The final component of TM is telemonitoring, which enables the monitoring of vital signs and the collection of medical information outside of the conventional clinical environment. These data facilitate the safe and early transition of care from hospitals to patients’ homes and allow caregivers to implement timely therapeutic interventions. Collected data from telemonitoring have the potential to effectively manage complications associated with cirrhosis [32-36] and transplantation care [27, 37], leading to a positive impact on readmission rates and improving patients’ quality of life [38-40]. Additionally, the data can serve as digital biomarkers to predict outcomes, understand the mechanisms of disease, identify impending complications, and guide early intervention to improve healthcare outcomes and prevent readmission [41, 42].

As a tertiary and transplantation centre, our liver department has been providing teleconsultations to guide on-site doctors in caring for patients with liver disease and assessing potential candidates for liver transplantations for over a decade. The social distancing policy restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic set in March 2020 and the consequent restriction of hepatology tertiary care led to the postponement of most planned outpatient services, diverting acute hospitalizations to regional, lower-rank institutions and deferring LT except for urgent indications. To prevent downgrading of outpatient care, we initiated TM to monitor health status, including quality of life, and offered advice in managing emergencies [43]. Simultaneously, with the help of TM, we optimized solutions for hospitalized patients at risk for COVID-19 infection and vulnerable patients after discharge [44]. International professional societies have released recommendations encouraging the implementation of TM in daily practice, particularly telemonitoring, which seemed to be an answer for a large cohort of patients [45, 46]. Although in-person clinic visits have resumed in the post-pandemic period, TM has remained a component of our healthcare portfolio due to its potential to fill pre-existing healthcare gaps and meet patient needs.

The number of patients enrolled in the whole TM study increased between the pilot (TM1, 24 patients) and subsequent phase (TM2, 71 patients). While the profile of both cohorts was similar, in the TM2 phase, patients had a higher average age (53 vs. 66) and were more acutely ill (more patients with ACLF than in TM1: 8% vs. 24%); likewise, the number of post-liver transplantation patients nearly doubled (25% vs. 44%). Despite there being a higher number of patients in TM2 as compared to the TM1 phase, the number remained relatively low in comparison to all hospitalized patients. In TM2, patients were selected based on their willingness to participate, mental status, technical literacy, and internet coverage, enabling telemedical monitoring. Simultaneously, patients were selected based on the expected benefits of shortening or averting hospitalization on the one hand and accelerating early rehospitalization in the case of TM-registered deterioration on the other. This selection process focused on patients with complications of cirrhosis, such as ascites and infection, or patients with post-liver transplantation complications, such as infection, hypertension, and diabetes. We aimed at earlier discharge prior to full stabilization of health status, i.e., we shifted the discharge paradigm from “normalized” to “improved”; the initial impact on the pre-set variables might be seen as relatively modest: shortened hospitalization in 11.3% patients, averted/prevented hospital admissions in 14.1%, and accelerated rehospitalization in 11.3%. However, upgrading paradigms necessitates time and effort for mind- and system-changing processes to take place. On the other hand, our findings highlight the system-related and economic potential of the TM-implementation process, which requires only en-route optimization, continuous feedback, recall policy evaluation, and identification and addressing of barriers.

Potential barriers may arise on both the patients’ and providers’ sides. During the pilot phase, we identified several of them, such as altered patient’s mental status (hepatic encephalopathy, health literacy) [47]; limited internet access; economic and social milieu [48]; technical skills and trust in technologies, partially associated with increasing age [49]; language barrier, present in marginalized groups such as ethnic minorities, etc. Although all patients in this study received necessary devices free of charge, socioeconomic status may represent an additional barrier in the implementation process in the future – outside the research [50]. It is important to acknowledge that these barriers have the potential to uncover hidden health inequalities. Therefore, it will be crucial to find ways to overcome them [51, 52].

Additional potential barriers were identified on the provider side. Despite physicians’ awareness of the benefits of TM and the increase in the number of enrolled patients between the pilot and subsequent phase, they were not fully able to integrate TM into their everyday decision-making process. Although studies indicate that the time required to incorporate clinical innovations into routine practice spans more than a decade [53], the implementation process can be enhanced by various means, including incorporating incoming data into the hospital information system. Another potential barrier could be dealing with a large volume of data and alerts coming from patients to providers. Some of these alerts may not be clinically significant and could be challenging to manage during off-hours; besides, reviewing alerts represents an additional workload for physicians alongside routine patient care. All these domains call for the innovation and adoption of advanced computing systems, big data analytics, and artificial intelligence. Creating an independent virtual ecosystem based on AI that is connected to the hospital system can significantly reduce the workload of physicians. Additionally, it can help in better and more comprehensive evaluation of incoming data, which can help in the timely identification of patients at risk of decompensation and rehospitalization. This, in turn, can enhance the overall quality of healthcare [54]. This vision represents one of the future directions of this project. An effective way to enhance the implementation of TM and reduce hospitalization rates is by using remote monitoring for other indications. Some potential areas where remote monitoring can be used are testing hepatic encephalopathy to prevent HE-related readmissions, particularly based on AI assessment of slower speech and longer word duration as a potential biomarker [55]. Telemedicine also holds the potential to manage malnutrition and frailty, monitor and encourage physical activity [56, 57], and address addiction and alcohol abuse [58]. For liver transplantation patients, a promising approach seems to be a home monitoring system connected to software allowing the recording and transfer of blood test results, symptoms assessment, medication reminders, and communication and education background [59].

The adherence of patients to telemedical monitoring in this group was relatively high, and when comparing the pilot and subsequent phases, it increased. The percentage of patients who completed measurements at the scheduled time reached as high as 81.7% in the subsequent phase (vs. 58.3%), comparable to adherence in a similar study [27]. Only 1.4% of patients chose to terminate the measurements based on their decision (vs. 12.5%). Furthermore, the deviation from planned measurements was only 13.0% (vs. 41.0%). Behind this increased adherence lies a more effective selection of patients indicated for remote monitoring based on the previously discussed selection criteria. Conversely, lower adherence to TM in the pilot phase may be associated with lower treatment adherence and relapses in alcohol use disorder. A significant factor influencing adherence is patient satisfaction with TM [40], which may be similar to or potentially greater than conventional in-person visits [60-62]. A crucial determinant of patient acceptance and willingness to participate in TM appears to be sufficient education and the presentation of benefits for healthcare [63], with active caregiver participation in technology-based interventions [64]. The time on TM was reduced in the subsequent phase compared to the pilot phase. However, this was not due to lower adherence but rather because of a shorter minimum remote monitoring period, which was implemented to rationalize the TM programme. Furthermore, the summary of the frequency of measurements for each parameter in both phases only serves as an overview since the monitoring timetable in the subsequent phase is personalized, and therefore adherence cannot be accurately reflected.

Although the impact of TM on shortened, averted, and timely addressed hospitalization in this study may seem relatively modest, overall remote monitoring positively affected the hospitalization rate in one-third of patients. Similar studies confirmed reduced readmission rates and improved quality of life in patients with decompensated liver disease and after liver transplantation managed through TM [27, 32, 37-39]. The positive impact on the management of diabetes and hypertension has been documented in several studies [65-67], and its usability was proven in early diagnosis and management of decompensated diabetes and arterial hypertension in one-third of patients after liver transplantation. The shift of healthcare services from hospitals to the patient’s home and the reduction in hospitalization days have significant economic implications. For instance, the use of telemonitoring interventions to manage cirrhotic ascites was estimated to reduce costs by US $167,500 for 100 patients over six months [68].

Another aspect of assessing the quality of TM implementation in real-world practice involves evaluating technical infrastructure. As an indicator in this analysis, we selected the speed of transferring measured data from the patient to the online database. The majority of measurements (87%) were recorded in the online database within 2 minutes, with the greatest delay observed in spirometry and blood pressure measurements. Delays exceeding 2 minutes may be attributed to varying internet connection speeds or device time settings. The high speed of data transfer ensures their prompt availability for evaluation, thereby enhancing the efficiency of healthcare provision.

This study suffers several limitations related mainly to its retrospective nature and the size of the cohort. The enrolment was not systematized and was left to the attending physician’s discretion. Additionally, selected patients were not being evaluated systematically and daily for early discharge on remote monitoring. Although patients managed by our tertiary liver unit are typically readmitted to our centre, when necessary, we lack information about potential readmissions to regional hospitals. Since the protocol for measuring vital signs was individualized, evaluating the overall adherence to each vital sign measurement was impossible. We also lack information on the number of lost data in the virtual sphere, false measurements and alerts, and the use of technical support to assess technical feasibility relevantly. By exploring and understanding these factors, we can improve the implementation process and address exact control endpoints for further study phases.

In conclusion, this retrospective cohort study demonstrated that telemedicine positively impacts the hospitalization rate, particularly in shortened, averted, and timely resolved hospitalizations. Furthermore, the adherence of patients to remote monitoring in this study was high and comparable with other similar studies. Despite identified limitations and potential barriers in the tertiary liver unit, TM has the potential to improve the quality of healthcare and reduce the cost of care. En route amendments to the protocol (TM2 vs. TM1) have resulted in improved adherence and decreased hospitalization rates. By addressing identified barriers and precision patient selection in terms of personalization and consecutiveness, the impact of telemedicine can be further increased.