Introduction

The burden of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is substantial across the world. In 2020, HCC ranked as the sixth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality globally [1]. Alarmingly, the incidence and mortality rates of HCC are projected to increase by 55% between 2020 and 2040 [2]. While hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection remain the main risk factors for HCC, the importance of other contributors is gaining recognition. These include obesity, diabetes mellitus, and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) [3], which is a growing concern in the Southeast Asia region, particularly Malaysia.

The American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD), the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL), and the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) recommend liver ultrasound as the standard surveillance tool for individuals at risk of developing HCC [4-6]. However, the sensitivity of ultrasound in detecting HCC has been documented to be relatively modest, ranging from 40% to 80% [7, 8]. Ultrasound effectiveness heavily relies on the operator’s skill, and its performance can be hindered by factors such as obesity, ascites and nodular cirrhotic liver [9]. This limitation translates to a concerning miss rate of 30% to 40% for HCC tumours potentially going undetected during ultrasound screening, leading to delayed diagnosis at a later stage. In recognition of ultrasound’s limitations in detecting HCC, α-fetoprotein (AFP) is employed as an adjunct biomarker in the surveillance protocol. Multimodal HCC surveillance strategies incorporating both ultrasound and AFP have only demonstrated a modest 6% to 8% improvement in supplementary detection rate [10]. Furthermore, AFP has a limited diagnostic utility in the early stages of HCC. Notably, up to 40% of HCC patients may present with negative AFP levels [11].

Two new serum biomarkers have been evaluated for HCC surveillance: lection-reactive α-fetoprotein (AFP-L3) and protein induced by vitamin K antagonist II (PIVKA-II). AFP-L3 is a sub-fraction of AFP that carries higher specificity, aiding in differentiating HCC from other benign liver diseases causing elevated AFP levels [12]. Elevated AFP-L3 has been observed as an early indicator of HCC development, especially in cases where AFP levels are low and ultrasound findings are negative [13, 14]. PIVKA-II, a deviant form of prothrombin produced by hepatocellular carcinoma cells, has gained traction as both a diagnostic and prognostic test [15]. Several studies have indicated that, alone or combined with AFP, it offers superior diagnostic efficacy for HCC [16, 17]. Additionally, PIVKA-II trends may correlate with treatment response following locoregional therapy [18].

The GALAD model, a serum-based tool for predicting the probability of HCC in high-risk populations, incorporates three serologic biomarkers – AFP, AFP-L3, PIVKA-II – and two demographic risk factors: age and gender [19]. For detecting HCC, the GALAD model has been found to outperform AFP and liver ultrasound [20, 21]. The diagnostic efficiency of GALAD was observed to be outstanding in diagnosing early-stage HCC [22]. However, the biomarker performance differs with geographic region mainly due to diversity in patients’ characteristics and ethnicity, and differences in the aetiology. The effectiveness of the GALAD model has been confirmed through validation in various regions, including Europe, Japan, and the United States, but has not yet been evaluated in Malaysia and Southeast Asian cohorts.

The objective of this research was to assess and compare the sensitivity, specificity and diagnostic efficacy of each biomarker, namely AFP, AFP-L3, PIVKA-II and the GALAD score, in screening HCC in Malaysian cohorts.

Material and methods

Study design

This was a single-centre, case-control study involving patients with HCC and cirrhosis at the gastroenterology clinic and wards, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre (UKMMC) from February 2022 to January 2023. The study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) (FF-2022-048).

Sample size

HCC prevalence in Malaysia is 4.53 per 100,000 population. The incidence risk is further amplified in chronic liver disease (CLD) and patient with cirrhosis. At the hepatology clinics at UKMMC, we observe a considerably higher prevalence of HCC among patients with underlying liver disorder, reaching approximately 10%. We determined the minimal sample size required for sensitivity and specificity tests using the established table developed by Bujang Ma and Adnan TH using PASS software [23]. This analysis indicated that a minimum sample size of 120 was necessary for the control group and 12 for the group of patients with HCC. Our study achieved the required power and sample size for analysis.

Study population

In this single-centre study, we enrolled a total of 44 newly diagnosed HCC patients and 179 control subjects from February 2022 to January 2023 at the UKMMC in Malaysia. In this study, the diagnosis of HCC followed the EASL guidelines and was based on either pathology or imaging. The disease stage was assessed using the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system. The control group in this study consisted of patients with HBV, HCV, MAFLD, and liver cirrhosis. Liver cirrhosis was diagnosed through either imaging or histopathological examination.

Measurements of serological biomarkers

A minimum of 6 ml of venous blood was drawn from subjects recruited in the clinic or wards. Four millimetres of the venous blood was sent for biochemical investigations, while the remaining 2 ml was centrifuged immediately and stored frozen at –80°C until analysis. The measurement of AFP, AFP-L3, and PIVKA-II was conducted using the μTASWako i30 microfluidic fully automated immunoanalyzer. This instrument has an assay sensitivity of 0.3 ng/ml for AFP, and the measurement of AFP-L3 was performed when AFP levels exceeded 0.3 ng/ml.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics software, version 26. We compared median and interquartile range of serum parameters between the HCC and control groups using the Mann-Whitney U test, and the p-values were calculated. We calculated the GALAD score in estimating the risk of HCC using the following formula:

GALAD = (–10.08 + 0.09 × age) + (1.67 × gender) + 2.34 log10 (AFP) + (0.04 × AFP-L3) + (1.33 × log10 PIVKA-II)

In this equation, gender is assigned a value of 1 for male and 0 for female.

Sensitivity and specificity were analysed for every single serum biomarker namely (AFP, AFP-L3, and PIVKA-II) and the GALAD score. We used cut-offs of 10 ng/ml for AFP, 10% for AFPL3, 40 mAU/ml for PIVKA-II, and −0.63 for the GALAD scores [24, 25]. The optimal cut-off value was established using Youden’s index. The diagnostic performance of AFP, AFP-L3, PIVKA-II and GALAD scores was assessed through receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis. All the ROC curves were compared using the DeLong et al. method [26].

Results

Patient characteristics

In this study, 44 new HCC patients and 179 controls with liver cirrhosis were enrolled. As shown in Table 1, a significant male predominance was observed in the HCC group, with a male-to-female ratio of 6.3 to 1. The median age for the HCC and control groups was 64.2 ±11.3 and 64.6 ±10.4 respectively. The majority of the HCC patients had HBV infection, 59.1% (22), followed by MAFLD, 22.7% (n = 10), HCV 13.7% (n = 6), alcohol-related liver disease, 6.8% (n = 3), and others, 6.8% (n = 3). The distribution in the control group shared a similar pattern as the HCC group, in which HBV (50.3%) was the most prevalent, followed by MAFLD (35.2%). The majority of patients were in Child-Pugh stage A, accounting for 45.4% of HCC patients and 64.8% of controls. No significant differences were observed in terms of patients’ age, ethnicity, aetiology and Child-Pugh class between the two groups.

Table 1

Patient demographic characteristics for both the hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and control groups, including age, gender, ethnicity, aetiology and Child-Pugh class

As shown in Table 2, most of the HCC cases were diagnosed at an intermediate or late stage (BCLC B, C and D), accounting for 84.1% of cases, while only 15.9% (n = 7) of the patients were diagnosed at an early stage (BCLC 0 and A). Among the HCC patients, 35 were found to have a tumour size of more than 3 cm.

Biochemical and biomarker levels

Patients with HCC exhibited significantly more advanced liver derangement compared to the control groups. This was evident in elevated levels of total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels in the HCC group compared to controls. Conversely, albumin levels were lower in HCC patients. Table 3 summarizes the serum biochemistry and biomarker levels for both HCC and control patients.

Table 3

Blood biochemical parameters and serum biomarker levels in both hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients and control group

The median serum marker levels of AFP, AFP-L3, PIVKA-II, and the resulting GALAD score were notably higher in HCC than the control group (AFP 41 ±1152.2 vs. 3 ±41.8, p < 0.0001; AFP-L3 15 ±329.94 vs. 0.0 ±7.59, p < 0.0001; PIVKA-II 400 ±23503 vs. 19 ±139.07, p < 0.0001; AFP + PIVKA-II 14.07 ±6.43 vs. 6.38 ±2.14, p < 0.0001; GALAD 2.15 ±15.02 vs. –3.08 ±1.77, p < 0.0001).

Performance of biomarkers in HCC detection

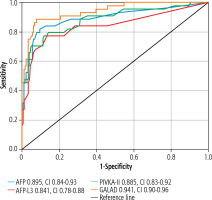

ROC curves were plotted to analyse the performances of AFP, AFP-L3, PIVKA-II and GALAD models in HCC detection, as shown in Figure 1. The AUC for AFP was 0.895 (with a confidence interval [CI] of 0.831-0.959 and p-value < 0.0001), indicating that AFP had a higher diagnostic performance than AFP-L3 (0.841, CI: 0.761-0.921, p < 0.0001) and PIVKA-II (0.885, CI: 0.821-0.948, p < 0.0001). GALAD was ob-served to have the best diagnostic ability with the highest AUC (0.941, CI: 0.901-0.980, p < 0.0001) compared with a combination all individual biomarkers. The ROC curves were compared among individual biomarkers, and their differences were not statistically significant (AFP vs. AFP-L3, p = 0.17; AFP vs. PIVKA-II, p = 0.80). However, the GALAD model was statistically significant (GALAD vs. AFP, p = 0.03; GALAD vs. AFP-L3, p = 0.01), and the comparison of GALAD vs. PIVKA-II was not significant, p = 0.077.

Fig. 1

ROC curves of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) for the GALAD scores and its individual components (AFP, AFP-L3 and PIVKA-II). GALAD attained the highest AUC compared to AFP, AFP-L3 and PIVKA-II

As presented in Table 4, optimal cut-off values for AFP, AFP-L3, PIVKA-II, and GALAD were determined. To distinguish between HCC and controls, AFP exhibited the same sensitivity as PIVKA-II of 79.5%. However, AFP had a higher specificity of 91.6% compared to PIVKA-II (84.9%) at a cut-off value of 10 ng/ml, which makes it the best single biomarker, whereas AFP-L3 only had a sensitivity of 59.1% and specificity of 94.9% at a cut-off value of 10%. However, combining these markers in the GALAD model yielded improved sensitivity (84.1%) and specificity (93.8%) at a cut-off of –0.63. At the optimal cut-off value of –1.03, sensitivity further increased to 88.6%, while specificity remained high at 92.2%.

Table 4

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) for both the standard and best cut-off value of biomarkers in the detection of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

| Parameter | Cut-off value | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Youden index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard cut-off | ||||||

| AFP (ng/ml) | 10a | 79.5 | 91.6 | 70 | 94.8 | – |

| AFP-L3 (%) | 10a | 59.1 | 94.9 | 74.3 | 90.4 | – |

| PIVKA-II (mAU/ml) | 40a | 79.5 | 84.9 | 56.5 | 94.4 | – |

| GALAD | –0.63b | 84.1 | 93.8 | 77.1 | 96.0 | – |

| Best cut-off | ||||||

| AFP (ng/ml) | 10 | 79.5 | 92.2 | 70 | 94.8 | 0.717 |

| AFP-L3 (%) | 6.5 | 77.3 | 86.6 | 58.6 | 93.9 | 0.639 |

| PIVKA II (mAU/mL) | 40 | 79.5 | 84.9 | 56.5 | 94.4 | 0.656 |

| GALAD | –1.035 | 88.6 | 92.2 | 73.5 | 97.1 | 0.808 |

The sensitivity of each biomarker and the GALAD model was studied at different tumour stages according to BCLC, as shown in Table 5. The GALAD model recorded the highest sensitivity of 100% for early-stage HCC (BCLC 0/A) compared to AFP (85.7%), AFP-L3 (85.7%) and PIVKA-II (71.4%) at their best cut-off value.

Table 5

Sensitivity of each biomarker and GALAD model in different stages according to BCLC

Discussion

Alpha-fetoprotein has been a mainstay in HCC screening for decades. However, its shortcomings as a standalone marker are gaining wider recognition, necessitating more sensitive and accurate alternatives. This study evaluated the ability of various tumour markers in distinguishing HCC from benign liver disease. Our results revealed significant elevations of all biomarkers in HCC patient compared to individuals with cirrhosis. The performance of PIVKA-II and AFP-L3 in detecting HCC was promising, suggesting their potential as reliable markers. Despite exhibiting a higher AUC value, and greater sensitivity and specificity, AFP did not show statistically significant differences when its ROC curve was compared to PIVKA-II and AFP-L3. Our findings align with observations from other studies in Asia and Europe [24, 27]. As a result, while PIVKA-II or AFP-L3 might not entirely replace AFP for HCC surveillance, they hold promise to play a complementary role in improving the accuracy of HCC diagnosis.

The GALAD score, initially developed at a single centre in the United Kingdom, was subsequently validated in a multi-centre, multi-continent study involving over six thousand patients recruited from Germany, Japan, and Hong Kong. This validation demonstrated excellent performance, with an AUC of 0.93 (95% CI: 0.92-0.94) in the Japanese cohort and 0.94 (95% CI: 0.93-0.96) in the German cohort using the cut-off of –0.63 [28]. Our study aimed to assess the GALAD score’s effectiveness in a Malaysian cohort for the first time. The results confirmed its excellent performance, with an AUC value of 0.941, in distinguishing HCC from benign liver disease. Notably, the GALAD score achieved the highest sensitivity of 84.1% and specificity of 93.8% at a cut-off of –0.63, surpassing the performance of individual biomarkers in our cohort. This superiority was particularly evident for early-stage HCC (BCLC stages 0/A), where AFP sensitivity is known to be inadequate. As a result, the GALAD model demonstrates potential as a supplementary tool for enhancing the early detection of HCC. Meanwhile, imaging modalities remain essential for definitive diagnosis and staging of HCC.

While a cut-off of –0.63 yielded an excellent result in our study, the sensitivity of the GALAD score further increased to 88.6%, with a slight drop in the specificity of 92.2% at a slightly higher cut-off value of –1.035. However, there is no established consensus on the specific cut-off values for this novel model when it comes to detecting any-stage HCC. The –0.63 cut-off value for the GALAD score used in many studies originated from data in British cohorts [19]. It is reasonable to believe that the optimal cut-off value might vary geographically due to differences in population demographics and underlying aetiologies of HCC. In a multi-racial country like Malaysia, with a diverse population that includes Malay, Chinese and Indian inhabitants, along with varying predominant aetiologies of HCC such as HBV and MAFLD, the need for a cut-off value tailored to the specific characteristics of the local population is clear. Unfortunately, the relatively small sample size in the present study may limit the ability to propose a specific cut-off for Malaysian or South East Asian cohorts. Nevertheless, the overall performance of the GALAD score at a cut-off of –0.63 remains highly promising.

The GALAD model demonstrates superior sensitivity and specificity compared to AFP, making it an excellent tool for integration into a national HCC surveillance programme, especially for the very high-risk population. HCC prognosis varies significantly based on early detection, highlighting the importance of effective surveillance. While Japan’s local guidelines recommend ultrasound with AFP, AFP-L3 and PIVKA-II for surveillance, studies have shown that HCC is often diagnosed at later stages in other regions despite surveillance efforts [29, 30]. Apart from its superior diagnostic ability, the GALAD score offers several other advantages that can significantly enhance the overall surveillance experience for patients. The superior specificity of the GALAD score reduces the false positive rate, a common problem with AFP-based screening. By accurately identifying patients with elevated AFP levels but without underlying HCC, the GALAD model can reduce the need for unnecessary radiological examinations. These examinations expose patients to ionizing radiation, which carries a potential health risk. Additionally, the GALAD model can lower healthcare costs by reducing the extensive diagnostic workup required for patients with false-positive AFP results. Simultaneously, it alleviates patients’ anxiety associated with unnecessary follow-up procedures. By streamlining the diagnostic process and minimising false alarms, the GALAD score can enhance patients’ adherence and compliance with the surveillance programme while providing a more accurate assessment of HCC risk.

Our study is limited by the relatively small sample size of 44 patients with HCC compared to 179 controls, particularly in early-stage HCC (BCLC stages 0/A) cohorts. This limitation is primarily attributable to patient recruitment from a single facility over a one-year period, compounded by the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Although our sample size met the minimum requirement, future studies involving larger and more diverse cohorts sampled from the Southeast Asian region would be invaluable. This would allow for in-depth subgroup analyses, particularly focusing on the performance of the GALAD score in detecting early-stage HCC across various aetiologies. Moreover, given the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and time constraints, a case-control study, despite its retrospective nature, remains a suitable design for validating the GALAD score.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that the GALAD model outperforms AFP, particularly in detecting early-stage HCC. This suggests the potential value of incorporating the GALAD score into the national HCC screening programme to facilitate the detection of HCC at curative stages and ultimately enhance the survival rate of the patients. Nevertheless, future studies with larger sample sizes in the Southeast Asian region would further corroborate our findings.