Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most frequently diagnosed malignancy among women worldwide, with approximately 1 in 8 women (13%) developing the disease during their lifetime [1]. In Greece, BC accounts for 8,987 new cases annually, leading to 2,431 fatalities [2]. A well-established risk factor for BC is prolonged oestrogen exposure, particularly in postmenopausal women, where obesity plays a pivotal role due to the excess oestrogen production by adipose tissue. Chemerin, also referred to as retinoic acid receptor responder 2, is an adipokine implicated in multiple physiological functions, notably in immune modulation and metabolic regulation. It serves as a chemoattractant protein, orchestrating the recruitment and activation of immune cells such as dendritic cells and macrophages. Its involvement in obesity, metabolic syndrome, and conditions like polycystic ovary syndrome highlights its potential significance in BC pathogenesis, probably due to its role in inflammatory and metabolic pathways linked to these conditions [3]. Given its dual role in immune regulation and angiogenesis, chemerin may represent a promising biomarker for assessing BC progression, and it could potentially guide prognostic evaluation in clinical settings.

Chemerin plays a crucial role in key biological processes, including angiogenesis, cellular proliferation, migration, and immune regulation, primarily through its interaction with G-protein-coupled receptors [4]. Initially, it is secreted as an inactive precursor, known as prochemerin, which requires proteolytic cleavage by specific enzymes to become biologically active [5]. Its main receptors – chemokine-like receptor 1 (CMKLR1), G-protein-coupled receptor 1 (GPR1), and cysteine chemokine receptor-like 2 (CCRL2) – are predominantly expressed in adipocytes and immune cells, as well as in breast and tumor tissues [6]. Chemokine-like receptor 1, first identified in 1996, mediates signalling upon chemerin binding, leading to the activation of Gi proteins. This interaction reduces cyclic adenosine monophosphate levels, ultimately triggering the phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and the activation of nuclear factor κB [7]. Cysteine chemokine receptor-like 2, on the other hand, primarily functions as a chemerin-binding receptor, concentrating the adipokine at sites where CCRL2 is highly expressed, such as activated endothelial cells. Beyond its autocrine functions, chemerin also exerts paracrine effects, significantly contributing to inflammatory processes [8]. Notably, tumor necrosis factor-αenhances chemerin synthesis in adipocytes. The precise role of chemerin in cancer remains controversial, as it has been reported to exert both tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressive effects. These dual functions appear to be mediated through different mechanisms, including the recruitment of innate immune cells such as natural killer (NK) cells and macrophages, as well as the stimulation of angiogenesis in endothelial cells [9]. Chemerin has also been linked to mammary tumorigenesis, obesity, and diabetes, potentially influencing BC development. Notably, its pro-angiogenic effects are thought to be driven by the upregulation and activation of matrix metalloproteinases, which play a central role in tumor vascularization [10–12].

Numerous studies have investigated chemerin expression in tumour tissues, establishing its potential as both a predictive and prognostic biomarker in BC. Its expression levels have been correlated with key clinical parameters, including body mass index (BMI), tumour size, and the presence of metastases – both lymphatic and distant – as well as tumour grading. Notably, chemerin expression exhibits an inverse relationship with oestrogen receptor (OR) and progesterone receptor (PR) levels in BC, suggesting a potential role in hormone receptor-negative disease subtypes [13]. Despite its apparent clinical significance, research on chemerin’s function in BC remains scarce, with only a limited number of studies exploring its implications in tumour progression and patient outcomes.

Chemerin has been widely studied across various malignancies, with its expression levels exhibiting tumour-specific variability. In several cancers, including melanoma, lung, prostate, liver, and adrenal tumours, chemerin expression is markedly reduced compared to normal tissue counterparts, suggesting a potential tumour-suppressive role [14]. In contrast, certain malignancies, such as mesothelioma and squamous cell arcinoma of the oral cavity, display elevated chemerin levels, indicating a more complex and context-dependent function of this adipokine [5]. Moreover, multiple studies have linked chemerin expression within the tumour microenvironment (TME) to clinical outcomes, with higher expression levels often being associated with improved patient survival [15]. However, despite its established involvement in other malignancies, the role of chemerin in BC remains poorly understood. Therefore, this study aims to comprehensively analyse chemerin expression in BC tissue and its surrounding matrix, specifically investigating its presence in tumour cells, fibroblasts, and adipocytes. Furthermore, it seeks to explore potential associations between chemerin levels and key clinico-pathological parameters, including tumour grade, lymph node involvement, hormone receptor status, and overall disease progression. By elucidating these relationships, our findings may contribute to a deeper understanding of the role of chemerin in BC pathophysiology and its potential as a biomarker for disease prognosis and therapeutic targeting.

Material and methods

This retrospective study conformed to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2013. From January 2015 to December 2018, a total of 77 Greek patients suffering from invasive breast carcinoma who attended the Breast Unit of the University Hospital of Patras were chosen. All patients included in this study were operated by the same surgeon. Patients who had only ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) and breast sarcomas were excluded. All the patients included in the study suffered from early breast cancer, and none of them received primary systemic therapy or underwent breast-conserving therapy or mastectomy. Concomitant presence of DCIS on surgical specimens was allowed. Paraffin blocks of the malignant tissues were obtained from each case. The eligibility criteria for the patient slides chosen for this investigation were based on the potential availability of adequate breast tissue. The clinical and pathological data are given in Table 1.

Table 1

Demographic and pathological characteristics of the female breast cancer patient

Diagnoses were made based on paraffin-embedded 4 μm tissue sections after haematoxylin and eosin staining. Tissues were classified according to histological subtypes as invasive breast carcinoma (ductal and lobular carcinoma) of different grades (n = 77). Invasive tumours were evaluated according to the Nottingham combined histologic grade (Elston-Ellis modification of the Scarff-Bloom-Richardson grading system) [16]. The staging of BC was determined based on the tumour-node-metastasis system based on definitions and recommendations of the European Society of Medical Oncology, 2015 [17].

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining was performed on 4 μm thick sections of each tumor’s most representative paraffin blocks. Slides were heated at 60°C overnight deparaffinised the next day in xylene, and heated again for 15 minutes. The slides were rehydrated by replacing graded alcohol with water. Heat-induced antigen retrieval was achieved by boiling sections in a citrate buffer, pH 6, in a microwave oven at 900°C for 2 minutes, after 300–400°C for 7 minutes, and then for 20 minutes at room temperature. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with peroxidase block solution for 20 minutes in a dark room, and the slides were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline 2 times. Sections were incubated for 30 minutes with primary rabbit polyclonal to chemerin antihuman chemerin antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) using a 1 : 400 dilution. Normal tissue adjacent to BC was also analysed as control. To ensure consistency, all immunohistochemical assessments were independently reviewed by 2 experienced pathologists who were blinded to clinical data and outcomes.

Interpretation and quantification of immunostains

We examined the positive signal for chemerin in BC tissue and in adipocytes and fibroblasts because these constitute part of TME. The cytoplasm and nucleus were the primary locations of the positive chemerin signal. The estimation of the score was semi-quantitative and based on the percentage and intensity of tumour cells that were positively stained. The intensity of chemerin staining was classified using the 4-point scale as 0 (no signal), 1 (weak staining), 2 (moderate staining), or 3 (strong staining). Percentage scores were assigned as 0, no staining; 1, 1–25%; 2, 26–50%; 3, 51–75%; and 4, 76–100%. The multiplication of their intensity score and area score was computed in each region. Thus, the score should range between 0 and 12. Chemerin immunostaining scores of 1–4 were classified as 1 (low expression), 5–8 as 2 (intermediate), and 9–12 as 3 (high expression) for statistical analysis.

The classification of chemerin expression into low, intermediate, and high levels was based on a composite scoring system that combined both the intensity and the percentage of positively stained cells, a method commonly employed in immunohistochemical evaluations. Specifically, the staining intensity (scored 0–3) was multiplied by the percentage score (scored 0–4), resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 12. This approach allows for semi-quantitative assessment while accounting for both staining strength and distribution. To facilitate statistical analysis and interpretability, the resulting scores were grouped into 3 categories: scores of 1–4 were classified as low expression, 5–8 as intermediate expression, and 9–12 as high expression. This classification strategy is consistent with previously published immunohistochemical scoring methods used in cancer biomarker research, and it aims to balance granularity with clinical relevance in differentiating levels of protein expression [18–20].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and categorical variables as numbers (percentages). We used the Kendall tau b test to determine if there is a correlation between a continuous and an ordinal variable, and the χ2 test or the Fisher’s exact test to detect whether the proportions for one categorical variable are different among values of the other ordinal variable. Correlation coefficients < 0.30 were considered as negligible; 0.30–0.50 as low; 0.50–0.70 as moderate; 0.70–0.90 as high; and > 0.90 as very high correlation [21]. The threshold for statistical significance was set at an αlevel of 0.05.

Results

A total of 77 women with primary BC were included. The mean age of patients was 62.42 ±13.74 years at a range of 34–89 years. Their pathological diagnosis was invasive ductal carcinoma in 77 cases (100%). Lymph node (LN) metastasis was present in 37.7% of cases, and the mean number of LN metastases was 2.05 ±4.45 with a range of 0–24. Tumour grading was moderate (grade II) in 33 cases (42.86%). Table 1 shows a summary of the demographic and pathological characteristics of the cases included in this study.

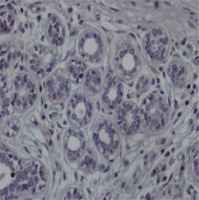

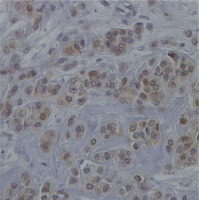

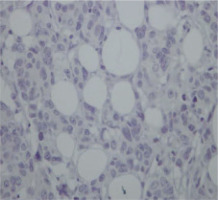

Of the 77 patients, 7 cases (9.1%) showed high expression levels of chemerin in malignant tissue and 36 cases (46.8%) showed negative staining for the protein chemerin (Figs. 1–3). There was a negligible negative association between chemerin tumor level and c-ERB2 level, which was statistically significant [τb(77) = –0.387, p < 0.001]. There was a low negative association between chemerin fibroblast level and c-ERB2 level, which was statistically significant [τb(77) = –0.277, p = 0.016]. There was a low positive association between chemerin fibroblast level and LN value, which was statistically significant [τb(77) = –0.236, p = 0.026]. There was a low negative association between chemerin adipocytes level and c-ERB2 level, which was statistically significant [τb(77) = –0.277, p = 0.016]. There was a low positive association between Chemerin adipocytes level and LN value, which was statistically significant [τb(77) = –0.236, p = 0.026] (Table 2). The varying levels of chemerin expression among tumor cells, fibroblasts, and adipocytes suggest that stromal and adipose components of the tumor microenvironment may play a more active role in modulating its influence on breast cancer progression. There was association between chemerin fibroblast and LVI, [χ2(1) = 5.302, p = 0.021] (Table 3). There was association between chemerin adipocytes and LVI, [χ2(1) = 5.302, p = 0.021] (Table 4). There was no association between chemerin tumor level and DCIS (p = 0.925), chemerin fibroblast (p = 0.435), and DCIS, nor chemerin adipocytes andDCIS (p = 0.021).

Fig. 2

Representative section of breast cancer tissue showing strong to moderate staining nuclear and cytoplasmic for the protein chemerin 40×

Fig. 3

Representative section of breast cancer tissue showing negative staining for the protein chemerin 40×

Table 2

Results of Kendall's tau tests

Table 3

Results of χ2 test for independence between chemerin fibroblast and LVI

Table 4

Results of χ2 test for independence between chemerin adipocytes and LVI

Discussion

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease with a complex interplay between tumor cells and the surrounding microenvironment, including stromal components such as fibroblasts and adipocytes. Increasing evidence suggests that adipokines, including chemerin, may play a crucial role in tumor biology by influencing cancer progression, immune evasion, and metastasis. However, the exact role of chemerin in BC remains insufficiently explored, particularly in relation to its expression in different cellular compartments of the tumor microenvironment [5, 13–15]. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to comprehensively investigate chemerin expression in BC by analysing its presence not only in tumour cells but also in fibroblasts and adipocytes, thereby providing a more integrated view of its potential diagnostic and prognostic significance. Our findings indicate a notable increase in chemerin expression in cases with LN metastases, suggesting a possible link between chemerin and metastatic dissemination.Conversely, reduced chemerin levels were observed in correlation with c-ERB2 (HER2) expression and LVI, raising questions about its potential role in tumour aggressiveness. The observed inverse correlation between chemerin expression and ER2 (c-ERB2) status is particularly noteworthy because HER2-positive tumours are often more aggressive. This may imply a compensatory role for chemerin or point to its reduced expression as a marker of tumour aggressiveness in this subtype. These observations highlight the dual nature of chemerin’s involvement in breast cancer, which may vary depending on tumour subtype cellular context, and interaction with other components of the tumour microenvironment. Further studies are needed to delineate the precise mechanisms underlying these associations and to determine whether chemerin could serve as a biomarker for disease progression or therapeutic intervention.

The tumour microenvironment plays a crucial role in BC progression, with dynamic interactions between tumour cells, immune components, fibroblasts, and adipocytes shaping disease behaviour. Adipocytes, in particular, have emerged as key regulators of cancer biology because their metabolic and secretory activities can significantly influence tumour cell proliferation, invasion, and immune evasion. The bidirectional crosstalk between adipocytes and cancer cells has been shown to induce phenotypic changes in both cell types, fostering a microenvironment that can either support or suppress tumour growth. One notable finding in this context is the role of chemerin as a modulator of the immune landscape within the TME. Pachynski et al. [6]were the first to demonstrate that increased chemerin expression in the BC TME could suppress tumour progression by recruiting NK cells and T-lymphocytes, thereby enhancing the local immune response.

These findings suggest that targeting chemerin-mediated immune activation could represent a novel immunotherapeutic strategy in breast cancer. In addition to immune cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) represent a dominant stromal component, accounting for approximately 80% of the total tumour mass in BC. Cancer-associated fibroblasts are highly heterogeneous in function, capable of promoting tumour growth through extracellular matrix remodeling, secretion of growth factors, and modulation of immune responses [22]. Their diverse roles add another layer of complexity to the TME, influencing how adipokines such as chemerin interact with various cellular components. Understanding the interplay between chemerin, CAFs, adipocytes, and immune cells may provide critical insights into its dual function in breast cancer, helping to refine its potential as a biomarker or therapeutic target. Interestingly, in other malignancies such as non-small cell lung cancer and oral squamous cell carcinoma, chemerin expression has shown variable prognostic value, further emphasising the complexity and context-specific nature of its role in tumour biology.

Adipokines, a diverse group of bioactive molecules secreted by adipose tissue, play a crucial role in tumourigenesis by modulating key biological processes such as inflammation, metabolism, and hormonal regulation. Their influence on BC progression has gained increasing attention because they can create a microenvironment that either promotes or suppresses tumour growth. Several adipokines, including leptin, resistin, apelin, and visfatin, have been implicated in cancer development due to their involvement in inflammatory pathways, insulin resistance, and the dysregulation of sex hormone production – factors that collectively contribute to a pro-tumourigenic environment [23]. Elevated circulating levels of these adipokines have been associated with increased cancer risk, tumour progression, and poorer clinical outcomes, particularly in obesity-related cancers such as breast cancer. Leptin, for instance, is known to enhance cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and resistance to apoptosis, while resistin has been linked to chronic inflammation and tumour aggressiveness. In contrast, certain adipokines, such as adiponectin, exhibit protective effects against tumour development. Adiponectin has been reported to possess anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative, and pro-apoptotic properties, counteracting the oncogenic influence of other adipokines [24]. Low adiponectin levels have been associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, particularly in obese postmenopausal women, further underscoring the complex interplay between metabolic factors and cancer progression. Given this dual role of adipokines in tumour biology, understanding their specific contributions within the BC microenvironment – including their interactions with chemerin – may provide novel insights into potential therapeutic strategies. Further research is needed to determine whether modulating adipokine levels could serve as a viable approach for BC prevention or treatment, particularly in patients with metabolic comorbidities such as obesity and diabetes.

The potential prognostic value of chemerin in BC has been highlighted by studies that report elevated chemerin expression in malignant breast tissues compared to adjacent normal tissues. Notably, its increased expression in lymph node metastatic tissue suggests that chemerin may serve as an independent predictor of poor prognosis in BC patients [13]. These findings point to chemerin’s potential role as a biomarker for aggressive disease, particularly in cases involving metastatic spread. The presence of chemerin in metastatic sites could indicate its involvement in the mechanisms of tumour dissemination, possibly by promoting angiogenesis, immune evasion, or tissue remodeling. If validated, chemerin could be integrated into clinical practice as a prognostic tool for assessing disease severity and guiding treatment decisions. However, conflicting evidence exists regarding the role of chemerin as a prognostic marker in BC. A study by Akin et al. [22] found no significant correlation between serum chemerin levels and BC stage, indicating that chemerin levels did not differ notably between metastatic and non-metastatic patients. This suggests that the relationship between chemerin and BC may be more complex than initially thought, possibly influenced by factors such as tumour subtype, microenvironmental conditions, and the method of chemerin measurement (i.e., serum versus tissue expression). The discrepancy between these findings underscores the need for further investigation into the precise role of chemerin in BC progression and its potential as a reliable prognostic biomarker.

Our study provides novel insights into the role of chemerin in BC, particularly in relation to its association with key prognostic factors. We identified a significant correlation between chemerin expression in BC tumour tissues and HER2 status, a finding that adds a new dimension to the existing body of research. Given that HER2-positive BC is often associated with increased aggressiveness and poorer clinical outcomes, this observation raises intriguing questions about the potential interplay between chemerin and HER2-driven tumour progression. Whether chemerin contributes to the oncogenic signalling pathways of HER2-positive tumours or represents a compensatory mechanism in response to aggressive tumour behaviour remains to be explored. Furthermore, our study is the first to report a direct association between chemerin expression in the tumour matrix and both LN involvement and LVI. These findings suggest that chemerin may play a role in BC dissemination, potentially by influencing tumour cell migration, adhesion, or immune cell infiltration within the tumour microenvironment. Given that LN metastasis and LVI are well-established indicators of poor prognosis, our results support the hypothesis that chemerin could serve as a marker of disease progression. Future studies are needed to elucidate the mechanistic pathways underlying these associations and to determine whether targeting chemerin-related signalling could offer new therapeutic opportunities in BC management.

One important limitation of our study is the absence of a true control group comprising healthy breast tissue from cancer-free individuals. While we included adjacent normal tissue on the same histological slides as a reference, this approach does not fully replicate the baseline expression profile of chemerin in truly non-malignant breast tissue. The use of adjacent normal tissue, although commonly accepted in tumour biology studies, may still reflect microenvironmental changes associated with the nearby tumour. Unfortunately, due to ethical and practical constraints, obtaining healthy breast tissue from individuals without cancer was not feasible within the scope of this study. Future investigations should aim to incorporate well-defined control cohorts, such as benign breast tissue from reduction mammoplasties or tissue banks, to better delineate the role of chemerin in breast tissue homeostasis and its potential dysregulation in carcinogenesis.

Limitations

Several limitations must be considered when interpreting the findings of this research. One key constraintis is the absence of a dedicated control group consisting of individuals without BC. While normal tissue adjacent to malignant lesions was analysed as a reference, it was included on the same histological slides as tumour specimens, which may not fully capture differences between cancerous and truly healthy breast tissue. Future studies should incorporate well-defined control cohorts to better delineate chemerin’s role in BC development and progression.

Another important factor to consider is the potential influence of external variables, such as diet and physical activity, on adipokine levels, including chemerin. It is well established that lifestyle factors modulate adiponectin levels, which in turn may impact chemerin expression and its biological activity in BC [24]. Therefore, a more comprehensive approach is needed to assess these variables systematically. Therefore, a more comprehensive approach is needed to assess these variables systematically.

Another limitation of this study is the absence of multivariate statistical analysis, such as logistic regression models, which could have helped to verify the independence of the observed associations between chemerin expression and clinic-pathological parameters. Given the relatively small sample size (n = 77), we opted to use univariate and bivariate statistical tests to minimise the risk of overfitting and to preserve statistical validity. However, we acknowledge that multivariate models would enhance the robustness of the findings by accounting for potential confounding variables. Future studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to incorporate multivariate analyses and validate the independent predictive value of chemerin expression in BC.

To gain a deeper understanding of the relationship between chemerin and BC, future research should adopt a standardized methodology that includes a thorough evaluation of patient medical history. Critical aspects to consider include menstrual and menopausal history, presence of metabolic disorders such as diabetes mellitus, family history of BC, and other relevant comorbidities. Additionally, integrating detailed physical examinations, particularly measurements of BMI, could help clarify the complex interplay between obesity-related metabolic alterations and chemerin expression in breast cancer. A well-structured, controlled cross-sectional study design would be instrumental in determining whether chemerin serves merely as a byproduct of metabolic dysregulation or plays a more active role in BC pathogenesis. Moreover, the expression levels of chemerin receptors such as CMKLR1, GPR1, and CCRL2 were not evaluated in this study. Their inclusion in future analyses may provide further insight into chemerin’s functional activity in the tumour microenvironment.

Conclusions

In summary, this study provides new insights into the expression of chemerin in both BC tumour cells and tumor cells and the surrounding tumor microenvironment. The findings indicate that chemerin levels are not significantly associated with BC stage, OR, or PR status. However, the broader role of adipokines in BC remains a promising area of research, as they hold potential as diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive biomarkers, offering valuable insights into disease progression, inflammatory processes, and overall patient outcomes. This study represents an initial exploration of chemerin’s involvement in BC, laying the groundwork for further research. Future investigations will expand upon these findings by examining additional adipokines, including visfatin, adiponectin, and lipocalin 2, in a larger patient cohort. Given the exploratory nature of the current results, studies with larger and more diverse sample size are essential to clarify the precise role of chemerin in BC pathogenesis, tumour progression, and metastatic potential. Furthermore, identifying novel therapeutic targets based on chemerin-related pathways could contribute to the development of innovative treatment strategies. For a more comprehensive understanding of chemerin’s function in breast cancer, future research should take into account external influences such as physical activity, dietary habits, body mass index, metabolic conditions like diabetes, and C-peptide levels. Because OR, PR, and HER2 are well-established biomarkers in BC classification and treatment decisions, further investigation into the interplay between chemerin and these molecular markers could provide deeper insights into its potential role in BC aggressiveness and therapeutic response.