Introduction

Viral hepatitis is a disease caused by a variety of viruses, five of which are categorized as primarily hepatotropic [1]. Hepatitis as a health threat, both individual and public, has been a significant challenge for many centuries, causing epidemics since ancient times, with documented outbreaks as far back as 5,000 years ago in China [2]. The group of primary hepatotropic viruses includes those designated by five consecutive letters of the Latin alphabet: A (HAV), B (HBV), C (HCV), D (HDV), and E (HEV) [1].

Despite their shared ability to infect hepatocytes, they are taxonomically and genomically distant. They also differ in transmission mode, geographic distribution with areas considered endemic, methods of treatment, and prevention [1]. Notably, specific prophylaxis in the form of vaccination has been available for many years only for HAV and HBV, and a vaccine against HEV has recently been licensed, while all efforts to develop a HCV vaccine have led to failure so far [3, 4]. These differences translate into clinical consequences. The non-enveloped viruses, HAV and HEV, are transmitted by the oral-fecal route, through contact with an infected person or ingestion of contaminated products, and infections caused by them are usually asymptomatic or mild. When symptoms do occur, they manifest as acute forms that do not require specific antiviral treatment, only symptomatic therapy [5, 6]. Infections with the larger enveloped HBV and HCV viruses, which are transmitted via blood-borne, sexual, or vertical routes, can result in not only acute but also chronic hepatitis, requiring complex and costly therapies. HBV and HCV viruses chronically infect tens of millions of people globally, making them the leading causes of cirrhosis, liver cancer, and hepatitis-related deaths [7, 8]. Whereas as the majority of HBV infections resolve spontaneously, spontaneous clearance of HCV occurs only in 15-25% of cases, with the majority of individuals progressing to chronic disease [9]. Of the primary hepatotropic viruses, HDV is the most unique, as it can only infect people with HBV infection, and such co-infection results in a more severe course of the disease, more serious clinical consequences, and higher mortality [10].

According to the most recent report of the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2022, approximately 254 million people worldwide were living with chronic HBV infection, of whom about 5% were co-infected with HDV, while the number of patients chronically infected with HCV was approximately 50 million [11]. The same report estimated that the number of deaths due to viral hepatitis rose from 1.1 million in 2019 to 1.3 million in 2022, making it the second most common infectious cause of death globally. Unfortunately, for the majority of affected individuals, testing and treatment remain inaccessible [11]. HAV and HEV infections are far less of a challenge. According to WHO estimates, hepatitis A caused 7,134 deaths worldwide in 2016, accounting for 0.5% of all viral hepatitis-related deaths [12]. Hepatitis E was responsible for about 44,000 deaths in 2015, accounting for 3.3% of all viral hepatitis deaths [13].

In response to the public health threat posed by parentally transmitted hepatitis B and C, the WHO has set an ambitious target for their global elimination: a reduction of 90% in new infections and 65% in deaths by 2030 compared to 2015. Key actions to achieve this goal include increasing education about viral hepatitis, implementing universal hepatitis B vaccination, ensuring access to hepatitis B treatment, and ensuring access to safe and highly effective direct-acting antiviral (DAA) drugs for hepatitis C [14]. However, scientists estimate that up to 80% of high-income countries will not reach this goal set by the WHO [15].

Among the many reasons for the failure to achieve the WHO target is the COVID-19 pandemic, which significantly disrupted healthcare systems worldwide, including in Poland, due to the overwhelming demand for medical care for COVID-19 patients. This diversion of resources and public attention had a notable impact on diagnosing and treating other diseases, including viral hepatitis [16, 17].

This retrospective study aimed to analyze long-term epidemiological patterns and trends in the burden of viral hepatitis caused by HAV, HBV ±HDV, HCV, and HEV in Poland. The study sought to understand the epidemiology of viral hepatitis infections and mortality, particularly examining how these trends were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Material and methods

Study design

A descriptive epidemiological study was performed using the nationwide retrospective data for viral hepatitis infection and mortality in Poland. For this study, we used all newly diagnosed cases of the main types of viral hepatitis infection (HAV, HBV ±HDV, HCV, and HEV), as well as deaths caused by particular types of hepatitis, over the years 2009-2023. The starting year of data analyses was 2009, considering comparable data for all types of viral hepatitis presented according to a uniform methodology [18]. All registered data covered each successive calendar year for viral hepatitis infections until 2023 and for deaths to 2022, as the last years in which complete data on infections were available. The analysis was based on anonymous secondary data from a publicly accessible national registry; therefore, the approval of the local Bioethics Committee was not required.

Data sources and hepatitis infection variables

Information on diagnosed viral hepatitis infection was obtained from the Epimeld database, published by the National Institute of Public Health NIH – National Research Institute and the Chief Sanitary Inspectorate in Poland [19]. Data from the Central Statistical Office were used to analyze deaths from viral hepatitis. Diagnosed cases and deaths due to viral hepatitis were classified using the International Classification of Diseases version 10 (ICD-10) codes. We investigated data with ICD-10 codes related to viral hepatitis as follows: HAV (B15), HBV in total (B16.0, B16.1, B16.2, B16.9, B18.0, B18.1), including HBV with HDV (B16.0, B16.1, B18.0) and HBV without HDV (B16.2, B16.9, B18.1), HCV (B17.1, B18.2), HEV (B17.2); other (B17.0, B17.8, B18.8, B18.9, B19), and total (B15-B19). The rates of newly diagnosed hepatitis viral infection were calculated as the number of new cases in total and separately encompassing the main types of viral hepatitis per 100,000 population for each year. In order to analyze deaths from viral hepatitis infection in total and by main type of viral hepatitis, we used age-standardized mortality rates (ASMRs), calculated using the method of direct standardization and the 2013 edition of the European Standard Population as the reference population.

Statistical analysis

To assess the burden of newly diagnosed viral hepatitis infections during the last 15 years (2009 to 2023) and for mortality over 14 years (2009 to 2022), we used joinpoint regression [20]. This method allows us to examine long-term trends and analyze the changes in trends [21]. Joinpoint regression identifies joinpoints that connect different line segments to identify years in which a significant change in the slope of a linear trend over time occurs in the data. We started with the minimum of joinpoints (e.g., zero joinpoints, which is a straight line) and used a maximum of three joinpoints (corresponding to four-line segments). Estimated linear segments were presented as an annual percentage change (APC) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). A summary of the 2009-2023 period revealed the annual average percentage change (AAPC) and its 95% CI, calculated as a weighted average of partial trend APC. The trend was identified as increasing when the APC (or AAPC) value and its 95% CI were positive, and it was decreasing when negative. If APC (or AAPC) had a value from –0.5 to 0.5, the trend was defined as stable [20].

Additionally, the burden of new viral hepatitis infection and mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic was analyzed by calculating the percentage change in the rates of new viral hepatitis diagnoses and mortality.

All statistical calculations were conducted using the statistical package IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 24.0. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

General epidemiology of viral hepatitis

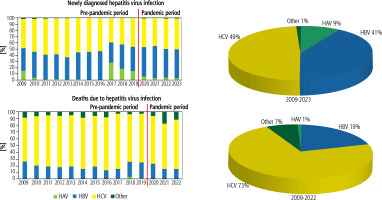

In Poland, a total of 85,265 new cases of viral hepatitis infection were recorded between 2009 and 2023, with a high proportion of these cases for HCV type (49%) and HBV type (41%). From 2009 to 2022, a total of 3019 deaths were recorded due to viral hepatitis infection, among which the HCV type predominated (73%) (Fig. 1). Deaths due to HBV infection accounted for 19%, including HBV infection without HDV superinfection, which was 16%.

Fig. 1

Distribution of newly diagnosed viral hepatitis infection and death (by hepatitis type) in Poland

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the distribution in rates of newly diagnosed viral hepatitis infection and mortality. The median value of the rate of newly diagnosed hepatitis viral infections for HCV and HBV types was 6.91 per 105 and 6.61 per 105, respectively. The lowest median value of newly diagnosed hepatitis infection occurred for HAV (0.29 per 105); in the case of HEV it was 0.05 per 105 (minimum 0.02 per 105, maximum 0.07 per 105) in the years 2022-2023. However, for mortality, the median of ASMR was very low for all types of hepatitis; especially, the data for ASMR of HAV were very unstable. The total median for ASMR due to hepatitis viruses was 0.67 per 105.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics for viral hepatitis infection and mortality in Poland

| Indicator | Median | Mean | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newly diagnosed infection rates per 100,000 population† | ||||

| HAV | 0.29 | 1.27 | 0.09 | 7.82 |

| HBV | 6.61 | 6.18 | 2.59 | 9.9 |

| HCV | 6.91 | 7.32 | 2.49 | 11.1 |

| Other | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.2 |

| HEV†† | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Total | 14.1 | 14.85 | 5.4 | 27.0 |

| Age-standardized mortality rates per 100,000 population††† | ||||

| HAV | 0.0 | 0.003 | 0.0 | 0.02 |

| HBV with HDV | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.17 |

| HBV without HDV | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.16 |

| HCV | 0.5 | 0.45 | 0.2 | 0.68 |

| Other | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.08 |

| Total | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.28 | 0.9 |

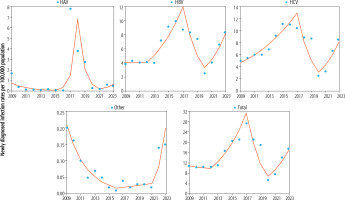

Joinpoint analysis of long-term trends in new viral hepatitis infections

The results of the joinpoint analysis of newly diagnosed viral hepatitis infection rates in the years 2009-2023 are presented in Table 2 and Figure 2. The results indicate fluctuations in the trend direction of hepatitis infections when they appeared in two (or three) joinpoints connecting a three-line (or four-line) segment of the trend. In the case of the total rate of newly diagnosed infection due to viral hepatitis, a four-line trend was observed, which in the initial period was flat and insignificant (ptrend > 0.05). In the second trend, there was growth (APC2012-2017 +25.8%, ptrend < 0.05), and then in the third segment, a decline was observed (APC2015-2020 –39.2%, ptrend < 0.05). Finally, in the fourth segment of the trend, there appeared a sharp increase for the total rate of newly diagnosed infection due to viral hepatitis (APC2020-2023 +35.9%, ptrend < 0.05). Dynamic changes were visible in the case of newly diagnosed HAV infection, and although initially there was a downward trend, there was very high growth of HAV infection in the next segment after 2015 (APC2015-2018 +341.8%). In the following years, the HAV trend turned negative, and in 2021, the infection rates were on the rise again. The HBV trend was quite similar to the changes that occurred for the total rate of newly diagnosed infection due to viral hepatitis, although a significant upward trend was visible in the second and fourth segments of the trend (APC2012-2017 +23.9% and APC2020-2023 +37.0%, respectively). HCV trends were significant in each of the three segments, with the first line being an upward trend (APC2009-2017 +13.5%). Later, the trend changed direction twice: in the second segment, it declined (APC2017-2020 –37.5%), and in the third segment, it again rose (APC2020-2023 +38.7%). For other viral hepatitides, first a downward trend was observed (APC2009-2016 –29.5%, ptrend < 0.05), and in later years, there was growth, which after 2021 was sharp (APC2021-2023 +146.8%, ptrend > 0.05).

Table 2

Trends of newly diagnosed viral hepatitis infection and mortality rates by type over the years 2009-2023 in Poland

| Type of viral hepatitis infection | Joinpoint analysis to identify changes in trends over 2009-2023 | AAPC | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trend for period 1 | APC | Trend for period 2 | APC | Trend for period 3 | APC | Trend for period 4 | APC | ||

| Newly diagnosed viral hepatitis infection | Trend over 2009-2023 | ||||||||

| HAV | 2009-2015 | –31.3 (–55.8, 6.7) | 2015-2018 | 341.8 (–67.4, 5881.5) | 2018-2021 | –69.0 (–97.7, 319.3) | 2021-2023 | 88.2 (–86.1, 2448.2) | 6.5 (–11.2, 27.7) |

| HBV | 2009-2012 | 0.4 (–23.9, 32.5) | 2012-2017 | 23.9* (3.9, 47.7) | 2017-2020 | –34.9 (–62.7, 13.4) | 2020-2023 | 37.0* (3.8, 80.9) | 3.0 (–2.4, 8.6) |

| HCV | 2009-2017 | 13.5* (9.2, 18.1) | 2017-2020 | –37.5* (–56.3, –10.5) | 2020-2023 | 38.7* (15.9, 65.9) | 0.4 (–6.0, 5.6) | ||

| Other | 2009-2016 | –29.5* (–38.4, –19.3) | 2016-2021 | 12.6 (–18.3, 55.2) | 2021-2023 | 146.8 (–10.5, 580.0) | –5.8 (–16.2, 6.0) | ||

| Total | 2009-2012 | –3.0 (–23.8, 23.6) | 2012-2017 | 25.8* (7.9, 46.6) | 2017-2020 | –39.2* (–62.6, –1.3) | 2020-2023 | 35.9* (6.7, 73.2) | 1.3 (–4.5, 7.4) |

| Mortality due to viral hepatitis infection | Trend over 2009-2022 | ||||||||

| HBV with HDV | 2009-2015 | –0.7 (–6.9, 5.8) | 2015-2022 | –14.4* (–18.6, –10.0) | –8.6* (–11.1, –5.9) | ||||

| HBV without HDV | 2009-2019 | –6.1* (–9.4, –2.7) | 2019-2022 | –22.9* (–38.8, –2.9) | –8.9* (–11.4, –6.4) | ||||

| HCV | 2009-2016 | 5.6* (0.8, 10.7) | 2016-2019 | –32.0* (–52.2, –3.3) | 2019-2022 | 0.6 (–15.6, 20.0) | –7.8* (–12.0, –3.5) | ||

| Other | 2009-2016 | –0.9 (–15.5, 16.2) | 2016-2019 | –40.4 (–81.9, 95.9) | 2019-2022 | 74.5 (–3.7, 216.3) | –6.8 (–14.0, 1.0) | ||

| Total | 2009-2015 | 5.8* (0.7, 11.2) | 2015-2020 | –21.0* (–28.1, –13.3) | 2020-2022 | 8.1 (–19.4, 45.1) | –7.7* (–11.2, –4.0) | ||

Fig. 2

Newly diagnosed viral hepatitis infection by type over the years 2009-2023 in Poland using joinpoint regression

The analysis throughout 2009-2023 showed that the AAPC outcome had a positive value in all types of newly diagnosed viral hepatitis infection, except for other viral hepatitis types, but these changes did not reach statistical significance (Table 2).

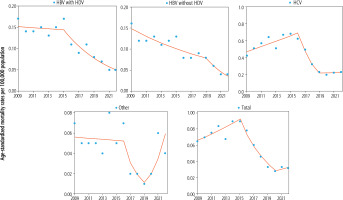

Joinpoint analysis of long-term trends in mortality due to viral hepatitis infections

The analysis of mortality due to viral hepatitis during 2009-2022 showed the changes with one joinpoint connecting two-line segments or two joinpoints connecting three-line segments of the trend (Table 2 and Fig. 3). For total ASMR due to viral hepatitis, the first trend was upward (APC2009-2015 +5.8%, ptrend < 0.05), while in the second segment of the trend, the direction was reversed into negative with high APC values (APC2015-2020 –21.0%, ptrend < 0.05). The third trend for total ASMR after 2020 revealed growth but did not reach statistical significance. Quite similar dynamics of the trend of total ASMR due to viral hepatitis were visible in mortality due to HCV. The first trend for ASMR due to HCV was upward (APC2009-2016 +5.6%, ptrend < 0.05), and in the second trend, there was a steep decline (APC2016-2019 –32.0%, ptrend < 0.05). However, in subsequent years, stagnation occurred (APC2019-2022 +0.6%, ptrend > 0.05). The direction of the trend in mortality due to HBV with and without HDV was downward, with one joinpoint connecting two-line segments. For HBV with HDV, the trend declined dynamically in the second trend (APC2015-2022 –14.4%, ptrend < 0.05). In the case of HBV without HDV, a significant downward trend was observed throughout the analyzed period, with a faster decline after 2019 (APC2019-2022 –22.9%, ptrend < 0.05). For ASMR, due to other viral hepatitis infections, the trend had three segments (the first two were negative and the third positive), but none of them reached statistical significance. Considering the changes in the whole analyzed period over 2009-2022, the AAPC values were negative for mortality of all types of viral hepatitis infection (Table 2).

Changes in burden of viral hepatitis during the COVID-19 pandemic

Evident changes in newly diagnosed viral hepatitis infection occurred between the initial and final year of the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 3). The pattern was uniform for all types of hepatitis and was characterized by an upward trend in the rates of these infections. Considering the change in 2023 vs. 2020 for the total rate of newly diagnosed infection due to viral hepatitis, a rise of +227.7% occurred, ranging from +89.6% for HAV to +400.0% for other viral hepatitides. For mortality due to viral hepatitis infection, changes were slower in comparison with newly diagnosed viral hepatitis infection. Total ASMR mortality due to viral hepatitis infection changed in 2022 vs. 2020 by +14.3%, and the range for types of hepatitis was from +15.0% for HCV to +100% for other viral hepatitides. For mortality due to HBV with or without HDV, the result was negative.

Table 3

Changes in the newly diagnosed viral hepatitis infection and mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic

| Type of viral hepatitis infection | Newly diagnosed viral hepatitis infection rates† | Change 2023 vs. 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2023 | ||

| HAV | 0.29 | 0.55 | +89.6% |

| HBV | 2.59 | 8.34 | +222.0% |

| HCV | 2.49 | 8.66 | +247.8% |

| Other | 0.03 | 0.15 | +400.0% |

| Total | 5.4 | 17.7 | +227.7% |

| Mortality rates due to viral hepatitis infection† | Change 2022 vs. 2020 | ||

| 2020 | 2022 | ||

| HAV | NA | NA | NA |

| HBV with HDV | 0.07 | 0.05 | –28.6% |

| HBV without HDV | 0.06 | 0.04 | –33.3% |

| HCV | 0.20 | 0.23 | +15.0% |

| Other | 0.02 | 0.04 | +100.0% |

| Total | 0.28 | 0.32 | +14.3% |

Discussion

In this nationwide study, we comprehensively assessed the epidemiology of viral hepatitis in Poland. Among viral hepatitis types, HCV predominated in newly diagnosed infection (49%) and mortality (74%), followed by HBV (41% and 15%, respectively). The greater burden of HCV compared to the other types of viral hepatitis has been attributed to the different ways of transmission, opportunities for vaccination, prevention, and treatment. Combating HCV infection in Poland remains a challenge, mainly due to the lack of an effective vaccine reducing the risk of infection and insufficient medical care. Importantly, it is becoming difficult for most countries, including developed ones, to achieve the WHO targets of eliminating HCV by 2030, considering the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted the eradication of hepatitis [22]. An important result of the present analysis was the estimation of HEV for newly diagnosed cases, which rapidly increased in the years 2022-2023.

We found significant fluctuations in trends of viral hepatitis in Poland that occurred in both periods – before the COVID-19 pandemic and during the pandemic. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, among viral hepatitis infections, the HAV type stood out, the burden of which was initially low; however, in 2017, the rate reached a very high peak. This was related to the HAV epidemic but resulted in a different pattern of this infection during the COVID-19 pandemic. A low rate of new diagnoses of HAV infection occurred in 2021, although rates for HBV and HCV were at their lowest a year earlier. It should be emphasized that the emergence of the HAV epidemic generally affected the curve of newly diagnosed viral hepatitis infection. Therefore, this trend did not match the shape of the overall mortality curve for viral hepatitis. This was mainly reflected in the significant downward trend in viral hepatitis infections that began in 2017 and, in the case of mortality, the downward trend since 2015.

In the period before the COVID-19 pandemic, an upward trend of HBV infection was observed until the turn of 2016/2017, which resulted in a more thorough epidemiological assessment related to the mandatory reporting of cases of infection by the laboratories from 2014 [23]. An upward trend of HCV infection was also observed, but unlike HBV, its determinants were different and were related to the introduction of a routine pregnancy screening program for HCV and the strengthening of epidemiological surveillance [24]. However, these two growth trends reversed, becoming negative from 2016 to 2019. In the case of HBV, this was due to the protective benefit of vaccination, which led to a reduction in acute HBV infection and thus a reduction in chronic HBV infection over time. The favorable trends in HBV infection in Poland were consistent with trends observed in many other countries [23, 25]. A spectacular reduction in HCV infection occurred as a result of the introduction of treatment with modern drugs such as DAA [24, 26]. The downward trend in HBV and HCV infections has reduced mortality, which confirms the improvement in preventive and therapeutic activities.

However, the negative trends of viral hepatitis infections ceased when the COVID-19 pandemic occurred, and in 2020, the values of the coefficients declined significantly compared to 2019. The infection rate values achieved in 2020 rebounded, and their upward trend continued until 2023, the last year in our analysis. The initial period of the pandemic reduced the ability to diagnose viral hepatitis infections and provide medical care to patients. Thus, case reporting was limited, but disease transmission was not reduced. The reorganization in healthcare institutions from hospital hepatology departments to COVID-19 treatment centers has complicated the treatment of patients with viral hepatitis, which has been observed around the world [27, 28]. It should be emphasized that the infection rate values achieved in 2020 rebounded, and their rise continued until 2023, the last year in our analysis. In some types of viral hepatitis (HBV, other), rates have exceeded pre-pandemic infection levels. This growth may result from a change in the awareness of medical staff about viral infections and an upturn in the sensitivity of the epidemiological surveillance system.

On the other hand, in addition to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, attention should also be paid to other possible sources of the spread of viral hepatitis, especially after February 2022, related to the waves of migration of war refugees from Ukraine [29]. Therefore, there is a need for intensive action on implementing complex interventions, including reducing the burden of viral hepatitis, and focusing on better methods of prevention and intervention of viral hepatitis, such as early diagnosis, linkage to care, and treatment.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive analysis of the burden of viral hepatitis, taking into account virus types based on data from national registers in Poland. It was especially important to create an epidemiological picture of HBV ±HDV and HEV, which has not been the subject of retrospective descriptive studies. The strengths of this study include the use of innovative joinpoint regression to examine long-term trends in infection and mortality due to viral hepatitis with the possibility of demonstrating their changes. Moreover, our analysis draws attention to a previously unexplored impact of the entire period of the COVID-19 pandemic on changes in the burden of viral hepatitis over 2020-2023.

We are aware that the present study had certain limitations. They are related to the imperfection of the infectious disease registration system, which results in the incomplete reporting of infection and mortality due to viral hepatitis. The problem of underestimation of registered data on viral hepatitis also occurs in other countries [30-32] and in the case of other infectious diseases [33]. It also should be noted that national registries mainly contain symptomatic cases of viral hepatitis among patients who have had contact with medical care. However, the reporting system for hepatitis virus infection does not specify the circumstances in which the infection was diagnosed. As a consequence, there are difficulties in determining the number of infections diagnosed during the implementation of preventive programs dedicated to hepatitis virus infection. An example is the increase in the number of reported HBV cases in connection with the change in the program of prevention of HBV infection reactivation in which the indications for prevention were expanded in the course of biological therapies, chemotherapy, and immunosuppressive treatment [34]. Unfortunately, the reported epidemiology of viral hepatitis in Poland may also be influenced by poor access to medical care and suboptimal diagnostics. On the other hand, during the COVID-19 pandemic in the years 2022-2023, newly diagnosed cases of HEV infection were recorded in the epidemiological surveillance system, which may indicate a change in the awareness of medical staff related to increased testing for this disease.

We did not examine infections and deaths due to viral hepatitis according to socio-demographic characteristics such as age, gender, and place of residence, which were analyzed in our previous studies [21, 23, 24]. However, other data on the characteristics of viral hepatitis infections related to routes of transmission of individual types of virus were not available. Despite these limitations, the analysis of infection and mortality due to viral hepatitis in Poland performed in this population-based study is an important source of information for taking intervention activities aimed at eliminating these infections.

Conclusions

In Poland, the epidemiology of viral hepatitis has undergone evident changes over the past 15 years, encompassing shifts before the COVID-19 pandemic and during the pandemic. Although infection and mortality due to viral hepatitis significantly declined until 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the elimination of hepatitis. Intensive and coordinated actions are necessary to reverse the unfavorable upward trends of infections. National strategies are needed to reduce the burden of viral hepatitis, focusing on better methods of prevention and intervention for viral hepatitis, such as early diagnosis, linkage to care, and treatment. Continued monitoring of trends in viral hepatitis infection and mortality is critical. Future studies should analyze the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on hepatitis-related health.