Introduction

Ultrasonography (US) is a fast, cheap, user- and patient-friendly, cost-effective, and safe imaging method that can be performed at the bedside without radiation. It is often used for the abdomen, neck and cervical area, breast and related clinical situations. In the recent decade, use for diagnosing diseases of the pleura, chest wall, diaphragm, and some lung parenchymal diseases including interventional procedures (US-guided thoracentesis) is becoming popular. Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS), Focused Assessment With Sonography in Trauma (FAST), Extended-FAST, and Bedside Lung Ultrasound in Emergency (BLUE) protocols are used in practice. Studies have proven the value of US in defining pleural adhesions, thoracentesis, catheter placement, and pneumothorax, hemothorax, and port incision locations.

Advances in medical technology have introduced portable, affordable, and bedside usable handheld-US (HH-US) devices into clinical practice more commonly. They are primarily used in intensive care units and various inpatient clinics, including emergency services. These devices provide urgent and bedside diagnostic support in certain clinical situations [1, 2]. Hand-held ultrasonography (HH-US) has limited experience and evidence in thorax imaging [1]. HH-US devices have gained popularity among thoracic surgery clinics due to their safety, lack of ionizing radiation exposure, and ability to provide real-time images for physicians. These repeatable imaging devices are increasingly used for diagnosing and treating various diseases, particularly pleural effusion [3]. The efficacy and reliability of these devices are evident in numerous research articles, indicating their increasing use in the short and long term.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we introduced a handheld ultrasound device into our clinical practice due to limitations of patient mobility in the hospital sites. The number of consultations requested for pleural drainage were high, with various diagnoses from many different clinics.

Aim

This study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic values of thoracic HH-US examinations and compare them with chest X-rays (CXR) and computed tomography (CT) findings and examine the effectiveness of handheld ultrasound in evaluating patients who were referred for consultation due to pleural effusion. This included using it in our learning process and establishing a habit of utilizing it in thoracic surgery consultations.

Material and methods

Between January 2020 and November 2023, patients referred to the thoracic surgery clinic for drainage due to pleural effusion who had evaluation of the pleural space indicated on chest radiography or thoracic tomography were also scanned with thoracic ultrasound. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patient data were analyzed retrospectively. Inclusion criteria were patients referred to thoracic surgery for consultation due to a differential diagnosis of pleural effusion, hemodynamically stable, had a pulse oximeter reading in room air above 90%, and provided written consent. Emergencies were excluded.

Ninety-one patients were included in the study. Thoracic HH-US examination was performed by the thoracic surgery clinic associate and research assistant team using an HH-US device (Philips Lumify C5-2 5-2 MHz Curved Array Transducer) in B, M, and color Doppler modes (Figure 1). All patients were first evaluated with US, and then underwent chest X ray or computed tomography. US technique included scanning the entire thorax, focusing on the symptomatic or clinically suspicious site, using a probe. The probe was moved transversely and longitudinally along intercostal spaces, oblique, lateral decubitus positions, parasternal line, middle and lateral clavicular line, and anterior. We used the Balik [4] formula to calculate the volume of pleural effusion. The patient stood supine with slight (15°) trunk elevation, with the transducer perpendicular to the dorsolateral chest wall. Measurements were taken at end-expiration. The operator measured the maximum distance (in millimeters) between the visceral and parietal pleura; pleural effusion volume (ml) = (measured distance) × 20. If the measured distance was 3 cm or less, it was considered minimal effusion and drainage was not applied. Clinical and radiological information was evaluated, including demographic findings, CXR, CT, HH-US, interventional procedures, and complications. CT images were accepted as the reference test and final diagnostic method by the radiologist. CXR and CT findings were compared with HH-US findings, and the sensitivities of both imaging methods were calculated.

Figure 1

Handheld US device and pleural effusion view on US. A – HH-US probe and screen. B – Pleural effusion and compressed lung parenchyma. C – Pleural adhesions and loculated pleural effusion

Statistical analysis

Mean, standard deviation, median, lowest, highest frequency and ratio values were used in the descriptive statistics of the data. Concordance between variables was investigated by kappa analysis. The program SPSS Statistics 28.0 (IBM – New York, United States) was used in the analyses.

Results

There were 57 (62.6%) males and 34 (37.4%) females. The mean age was 61.1 (18–95) years, with no significant difference. Demographic values, US indications, and clinical needs are listed in Table I. CXRs revealed unilateral pleural effusion in 36 (39.6%) cases, bilateral effusion in 6 (6.6%) cases, and 75 (82.5%) of cases requested a CT. CTs revealed unilateral pleural effusion in 61 (67%) cases and bilateral effusion in 14 (15.4%) cases. Radiology findings and catheter insertion data are shown in Table II.

Table I

Patient characteristics

Table II

Results

Sixteen patients underwent ultrasound, with only diagnostic thoracentesis (due to suspicion of malignancy) (effusion volume in the range 600–1000 ml), and catheter thoracostomy to relieve symptoms of dyspnea in 47 patients (effusion volume 1000 ml and above). In 6 patients there was no pleural collection requiring intervention (the common pathology in patients was lung atelectasis), and minimal effusion was diagnosed in 14 patients (effusion volume 600 ml and less). Chest tube insertion was performed in 7 patients, with two due to empyema and five due to accompanying pneumothorax (2 patients were detected by the US before effusion drainage and pneumothorax was detected in 3 patients after drainage). One patient with pleural effusion refused all surgical intervention.

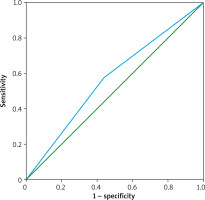

No tissue (parenchyma, bronchus, diaphragm) injury and no other complications occurred after the procedures. On average, HH-US examination procedures lasted 20 minutes per patient. The sensitivity of US in detecting fluid effusion compared to CXR was 83.3%, positive predictive value was 57.4%, specificity was 25.7%, negative predictive value was 56.3%, and concordance was 57.1% (Table III). The sensitivity of US in detecting fluid effusion compared to CT was 88.5%, positive predictive value was 85.7%, specificity was 35.7%, negative predictive value was 41.7%, and concordance was 78.7 (Table IV). When compared to CXR for the diagnosis of pleural effusion, US had similar results. The area under the ROC curve was 56.8% (Figure 2). When evaluated with US and CT, the diagnostic power of US was not less than CT. The area under the ROC curve was 46.4% (Figure 3).

Table III

US and CXR analyses

| Parameter | Effusion on CXR (-) | Effusion on CXR (+) | Sensitivity | Positive predictive value | Specificity | Negative predictive value | Concordance | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effusion with US | (–) | 9 | 7 | 83.3% | 57.4% | 25.7% | 6.3% | 57.1% | 0.330 |

| (+) | 26 | 35 | |||||||

Discussion

Our study analyzed the diagnostic value of thoracic HH-US examination in patients. As a result, we found that it has high diagnostic value for pleural effusions. It is safe, easily applied, feasible and also helpful in the treatment of these effusions. HH-US devices are commonly used in clinical units such as emergency departments [5, 6], but less commonly in pulmonary and thoracic surgery sections. These provide faster triage and performance in diagnosing massive pleural effusion, hemothorax, pneumothorax, tension pneumothorax, cardiac tamponade, and in referring patients for life-saving surgical interventions such as pericardiocentesis and tube thoracostomy, it has been demonstrated to provide faster triage and performance [7]. In one series, in 61 cases of thoracic trauma, the sensitivity of HH-US was 100% and the specificity was 92% for effusion [8]. Our results encourage the use of US more commonly and for it to be added to the education program of residents, even senior surgeons working in the field.

In many clinical units, including emergency rooms, HH-US devices are routinely employed as a supplemental diagnostic and imaging technique [5, 6]. There are limited data currently available on the use of HH-US in chest diseases and pleura. In 61 cases of thoracic trauma, Brooks et al. [8] found that HH-US had a 100% sensitivity and a 92% specificity for hemothorax in emergency evaluation. Thoracic HH-US was mostly utilized in diagnosis of pleural effusions in our daily work. Bedside evaluations with HH-US can help for detecting effusion and decision making for treatment, mostly for patients with mobility limitations. This would also be helpful for such procedures as echocardiographic examinations, complications after cardiac surgery, evaluation of the source of pulmonary embolism, evaluation of infective endocarditis, evaluation of aortic diseases, evaluation of intracardiac and pulmonary shunts, and evaluation of issues related to these procedures [9]. The article highlights the use of thoracic HH-US examination for diagnosing and treating pleural effusions, despite chest Xray and lung tomography having superior features. Additionally, HH-US provides real-time information, is less costly, and has a time advantage [10]. However, there are no data on clear indications for HH-US in the literature. Pleural thickening, a common pleural disease due to asbestos exposure, lung diseases, fibrotic diseases, tuberculosis sequelae, empyema, and chronic pleurisy, is often confused with pleural fluid, making the diagnosis harder. Thoracic HH-US examination and ‘fluid color sign’ are used for differential diagnosis of pleural fluid and pleural thickening. Pleural effusions cause color formation due to fluid movement with respiration in color Doppler mode, while pleural thickening does not cause fluid color symptoms. No cases with a preliminary diagnosis of pleural effusion were diagnosed with pleural thickening using an HH-US device, resulting in no complications.

The study involved patients who underwent thoracentesis using an HH-US device, with 47 (51.6%) undergoing HH-US guided catheter thoracostomy with a Pleuracan (Braun, Hessen, Germany). The study found that the HH-US device can help treat pleural effusion in real time, reducing complications such as pneumothorax, hemorrhage, hemothorax, liver, spleen, and adjacent organ injuries. It can also detect pleural adhesions and loculated pleural effusions [11]. Lisi et al. compared the HH-US device and lung radiography in cases with pleural fluid requiring thoracentesis. They found that the HH-US device integrates and completes the physical examination, providing additional information to CXR in diagnosing and treating cases with suspected pleural fluid [12]. The study found that pleural fluid was detected in 61 of 91 cases (67%) and thoracentesis was performed in 47 (51.6%) cases. There were no procedure-related major complications in any of the patients, except for 3 pneumothorax cases.

Also, there were no major complications in our study.

Lisi et al. [11] compared chest X- ray and the HH-US device in thoracentesis cases involving pleural fluid. They found that the HH-US device is a tool that integrates and completes the physical examination, giving CXR additional information for the diagnosis and treatment of cases involving suspected pleural fluid. They reported that thoracentesis was performed using the HH-US device. They evaluated 73 patients, 43 (63%) of whom underwent thoracentesis and had no post-procedural problems. They found that the thoracic HH-US examination took an average of 3.9 ±0.26 minutes per patient and that the method was both safe and effective. Comparable to previous research, our study found that 61 out of 91 cases (67%) had pleural effusion, and 47 (51.6%) cases underwent thoracentesis. With the exception of 3 pneumothorax cases, each patient received an average of 20 (SD 15 minutes) for our treatments, and none of our patients experienced any major post-procedural complication. Since patients were not recruited randomly or consecutively, selection bias should be considered.

The results of our investigation demonstrate the possibility of thoracic HH-US as a useful diagnostic aid in consultations for thoracic surgery. Here, we discuss the significance of our findings, the benefits and drawbacks of HH-US, and directions for further study and clinical application. In comparison to both CXR and CT, our investigation showed that HH-US has a high sensitivity for pleural effusion detection. Our results are supported by studies by Xirouchaki et al. and Koenig et al., which show that HH-US has a good sensitivity and specificity for pleural effusion detection [12, 13]. Moreover, there is a wealth of research demonstrating the usefulness of HH-US in directing thoracic procedures such catheter thoracostomy and thoracentesis. According to research by Laursen et al., HH-US can be safely and successfully used for thoracic procedures. Its ability to improve procedural accuracy and lower complication rates is particularly noteworthy [14]. When a prompt diagnosis is essential, HH-US can be a dependable and effective imaging technique for the preliminary evaluation and decision-making process in thoracic surgery consultations involving pleural effusion. HH-US devices are ideal for bedside examinations because of their mobility, simplicity of use, and ease of learning. This allows for prompt action when necessary.

This real-time feedback lowers the possibility of complications related to blind treatments and improves procedural precision. Our data showed similar sensitivity (83.3%) and positive predictive value (57.4%) between chest radiography (CXR) and US. Low values were found for specificity (25.7%) and negative predictive value (56.3%). The findings for positive predictive value (85.7%) and sensitivity (88.5%) between US and CT are greater. Low values are found for specificity (35.7%) and negative predictive value (41.7%). For diagnosis of pleural effusion, US seems to provide findings that are comparable to CXR. When compared to CT, US’s diagnostic efficacy is comparable to that of CT. With regard to USG, the area under the ROC curve (AUC) is 46.4%. These findings demonstrate that US is a useful technique for pleural effusion diagnosis.

HH-US is especially well suited for patient populations that are more susceptible to radiation exposure, such as pregnant patients.

Even though our study demonstrates the benefits of HH-US, it is crucial to recognize its drawbacks. Operator reliance is an important factor to take into account because conducting and interpreting HH-US examinations well calls for certain knowledge and training. Furthermore, in comparison to CT, HH-US may have a shallower penetration depth, which could make it more difficult to see tiny lesions or deeper structures. This is consistent with research by Mayo, Beaulieu, and Volpicelli et al., which highlighted the value of structured training courses for medical practitioners using HH-US in clinical settings [15, 16].

While HH-US has a number of benefits over conventional imaging modalities, it might only be a partial substitute for CT. The complementary roles of HH-US and CT in thoracic imaging have been highlighted by studies by Lichtenstein et al. and Alrajab et al., especially for assessing complex diseases and defining anatomical structures [17, 18].

Further research is needed to fully understand the potential of thoracic HH-US in clinical practice. Comparing HH-US to traditional imaging methods such as CT can provide valuable insights into its role in routine clinical care. HH-US is increasingly used in diagnosing and treating lung diseases, with new generation devices being used in many branches. The device’s immediate application at the bedside, ease of use, low cost, and time and labor advantages make it a valuable tool in thoracic surgery consultations. By leveraging real-time imaging, portability, and non-invasiveness, HH-US can enhance diagnostic accuracy, guide therapeutic interventions, and improve patient outcomes in managing thoracic diseases. Standardized application protocols and guidelines are crucial for safe and effective implementation. Creating educational programs for new generation residents also postgraduate courses for senior thoracic surgeons and training programs would expand the use in the field, thus helping clinicians in decision making and surgical interventions and also improving the quality of medical service.