Introduction

Heart failure is the final stage of many cardiovascular diseases, with a higher prevalence among individuals with diabetes [1]. Heart failure is a major health problem, impairing the quality of life of patients, leading to significant disability, and imposing a considerable burden on societies [2, 3]. Heart failure is associated with downregulation of fatty acid oxidation, enhanced glycolysis and glucose oxidation, decreased respiratory chain function, and impaired reserve for mitochondrial oxidative flux [4]. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors can improve myocardial energetics by providing β-hydroxybutyrate as a fuel for oxidation [5]. In addition, SGLT-2 inhibitors act as diuretics and simultaneously mitigate endothelial dysfunction and vascular stiffness [5]. Empagliflozin, a SGLT-2 inhibitor, is routinely prescribed for the management of type 2 diabetes and has shown promising effects on diabetes and other components of metabolic syndrome, such as hypertension [6, 7]. For instance, 12 weeks of treatment with 10 mg/day and 25 mg/day of empagliflozin respectively led to –3.44 mm Hg and –4.16 mm Hg decreases in systolic blood pressure and –1.36 mm Hg and –1.72 mm Hg decreases in diastolic blood pressure in patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertension [6]. Moreover, empagliflozin has been observed to significantly lower body weight in individuals with type 2 diabetes, which is of great clinical significance in the management of metabolic syndrome [7]. Due to the beneficial effects of empagliflozin in several components of metabolic syndrome, studies have increasingly assessed the effects of empagliflozin on cardiovascular outcomes [8].

Interestingly, the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial with 7020 patients with type 2 diabetes indicated that treatment with empagliflozin (10 mg or 25 mg daily) did not lower the risk of myocardial infarction or stroke, but significantly decreased the incidence of death from cardiovascular causes, hospitalization for heart failure, and death from any causes [8]. Another study with 2250 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, established cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease reported that compared to placebo, treatment with empagliflozin decreased the incidence rate of cardiovascular death by 29%, the incidence rate of all-cause mortality by 24%, the incidence rate of hospitalization for heart failure by 39%, and the incidence rate of all-cause hospitalization by 19% [9].

Based on the beneficial effects of empagliflozin on the clinical outcomes of cardiovascular diseases and heart failure, recent studies have investigated whether empagliflozin can reverse or decelerate the structural and functional alterations associated with heart failure [10–13]. Some of them showed that empagliflozin can significantly improve myocardial function [12, 13], whereas other studies reported non-significant results [10, 11], necessitating an updated meta-analysis to resolve this discrepancy. Therefore, due to discrepancies between the results of available clinical trials, the publication of new clinical trials in recent years, and the importance of cardiac remodeling in heart failure, this meta-analysis was conducted to pool data from randomized controlled trials and compare the effects of empagliflozin with placebo on cardiac structure and function in those with heart failure. Our findings can help the design of new guidelines to ameliorate adverse cardiac remodeling in individuals with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

Methods

Search strategy

Web of Science, PubMed, the Cochrane Library, and Scopus were searched from inception to December 20, 2024 using the following search keywords: (“empagliflozin”) AND (“echocardiography” OR “ejection fraction” OR “cardiac magnetic resonance imaging” OR “cardiac MRI” OR “cardiac MR”) AND (“heart failure”).

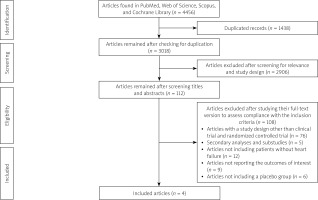

The search strategy is presented in Supplementary Material 1. Furthermore, we assessed the reference list of the retrieved trials or reviews to find more studies. The identified studies were then transferred to EndNote 8.0 and duplicates were deleted. We registered the protocol of this study in PROSPERO (CRD42024628400) and followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline to report this study [14].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) being a randomized controlled trial; (II) comparing the efficacy of empagliflozin with placebo for treating heart failure; (III) reporting at least one of the following efficacy outcomes: left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic volume, LV end-diastolic volume index, LV end-systolic volume, LV end-systolic volume index, LV mass, LV mass index, and left atrial volume index.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) the study was a review article, observational study, or case report; (II) absence of an empagliflozin or placebo group; (III) none of the target outcomes, including LVEF, LV end-diastolic volume, LV end-diastolic volume index, LV end-systolic volume, LV end-systolic volume index, LV mass, LV mass index, and left atrial volume index, were reported in the identified study; and (IV) empagliflozin was used in combination with other drugs.

Data extraction and outcome measures

Two authors performed the literature search and screened the retrieved studies independently. All discrepancies were resolved via consultation. By screening the titles and abstracts, the authors primarily assessed the relevance of the articles and investigated whether they conformed to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Thereafter, the full-text version of the remaining articles was assessed to determine their eligibility for inclusion.

The following data were collected: study characteristics (the first author name, publication year, trial registry, study design and settings, and country of study), population (sample size, gender, presence of diabetes, body mass index (BMI), and age), interventions (empagliflozin dose and length of intervention), and the outcomes (left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic volume, LV end-diastolic volume index, LV end-systolic volume, LV end-systolic volume index, LV mass, LV mass index, and left atrial volume index).

Risk-of-bias assessment

Two researchers independently assessed the risk of bias for each study, and all disagreements were resolved through consultation. We employed the revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) to determine the risk of bias for all studies included in this meta-analysis. The tool measures the risk of bias based on deviations from intended interventions, selection of the reported results, randomization process, missing outcome data, and outcome measurement and then provides an overall risk of bias for studies. In each domain, a series of questions, known as “signaling questions” were answered to elicit information about features of the trial associated with the risk of bias. A judgment about the risk of bias was made based on the answers to the signaling questions, and one of the following ranks was assigned to each domain: some concerns, low risk of bias, and high risk of bias [15]. A high risk of bias in any of the domains or “some concerns” in several domains was interpreted as a high overall risk of bias [15].

Statistical analysis

For all outcome measures, we extracted changes in mean and standard deviation (SD) of each group. We employed a random-effects model (DerSimonian-Laird) to calculate weighted mean difference (WMD) with 95% confidence interval (CI) and conducted this meta-analysis using Stata version 14.0 (StataCorp, TX, USA).

We used the χ2 test and I2 statistic to assess between-trial heterogeneity, and I2 greater than 50% was deemed high statistical heterogeneity.

Results

Systematic search results

In total, there were 508 records in PubMed, 399 records in the Cochrane Library, 989 records in Web of Science, and 2560 records in Scopus. Of 4456 articles, 1438 were removed due to duplication and 3018 articles remained. By screening the titles and abstracts, 2906 articles were excluded because of noncompliance with the inclusion criteria or lack of relevance. Next, we assessed the full text of the 112 remaining articles to evaluate their compliance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Eventually, 4 articles with 234 individuals in the empagliflozin group and 231 individuals in the placebo group were included in this meta-analysis [10–13] (Figure 1, Table I). All studies administered 10 mg/day of empagliflozin [10–13] (Table I). The length of treatment was 3 months in one study [11], 6 months in two studies [12, 13], and 9 months in one study [10]. Among the included studies, Santos-Gallego et al. included only non-diabetic patients [13], Lee et al. and Afshani et al. included patients with diabetes or prediabetes [10, 12], and Omar et al. included patients with or without diabetes [11].

Table I

Study characteristics

| First author name | Publication year | Age of participants (years, mean) | Country of study | Percentage of males | Initial LVEF | BMI [kg/m2] | Empagliflozin dose | Length of treatment | Percentage of patients with diabetes or prediabetes | Number of participants in the empagliflozin group | Number of participants in the placebo group | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afshani et al. | 2024 | 56 | Iran | 59.65% | < 40% | Not reported | 10 mg/day | 6 months | 100% | 52 | 52 | [12] |

| Lee et al. | 2021 | 68.7 | Scotland | 73.3% | 32.5% | 30.8 | 10 mg/day | 9 months | 100% | 52 | 53 | [10] |

| Santos-Gallego et al. | 2021 | 63.1 | United States | 64% | 36.3% | 29.7 | 10 mg/day | 6 months | 0% | 40 | 40 | [13] |

| Omar et al. | 2021 | 64 | Denmark | 85% | 35.5% | 29 | 10 mg/day | 3 months | 13% | 90 | 86 | [11] |

Risk-of-bias assessment

The revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) was used to determine the risk of bias for the included studies, which showed a low risk of bias for all included studies (Supplementary Material 2).

Meta-analysis

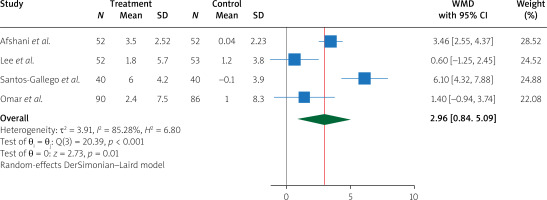

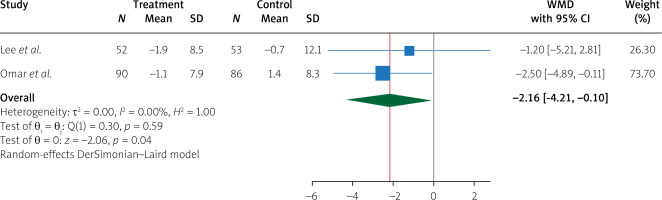

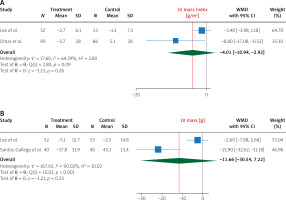

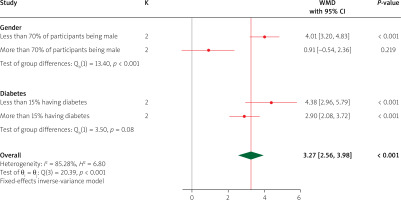

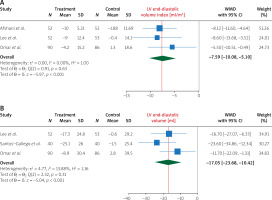

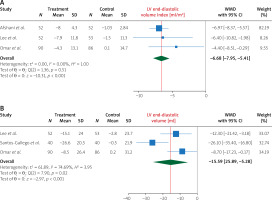

Pooling data from 4 studies, we found that, compared to treatment with placebo, treatment with empagliflozin 10 (mg/day) significantly increased LVEF (WMD 2.96%, 95% CI (0.84%, 5.09%), I2 = 85.28%) (Figure 2). In addition, compared to treatment with placebo, treatment with empagliflozin significantly decreased LV end-diastolic volume (WMD –17.05 ml, 95% CI (–23.68, –10.42), I2 = 13.88%) and LV end-diastolic volume index (WMD –7.59 ml/m2, 95% CI (–10.08, –5.10), I2 = 0.00%) (Figure 3). Similarly, compared to placebo, empagliflozin significantly decreased LV end-systolic volume (WMD –15.59 ml, 95% CI (–25.89, –5.28), I2 = 74.69%), LV end-systolic volume index (WMD –6.68 ml/m2, 95% CI (–7.95, –5.41), I2 = 0.00%) (Figure 4), and left atrial volume index (WMD –2.16 ml/m2, 95% CI (–4.21, –0.10), I2 = 0.00%) (Figure 5). However, compared to placebo, empagliflozin could not significantly change LV mass (WMD –11.66 g, 95% CI (–30.54, 7.22), I2 = 90.02%) and LV mass index (WMD –4.01 g/m2, 95% CI (–10.94, 2.92), I2 = 64.29%) (Figure 6).

Figure 3

The effect of empagliflozin compared to placebo on LV end-diastolic volume and LV end-diastolic volume index among patients with heart failure

Figure 4

The effect of empagliflozin compared to placebo on LV end-systolic volume and LV end-systolic volume index among patients with heart failure

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis for LVEF indicated that empagliflozin was significantly effective in both subgroups of diabetes (less than 15% of participants having diabetes and more than 15% of participants having diabetes), and there was no significant difference between the two subgroups. Also, regarding the percentage of males, empagliflozin more effectively increased LVEF in studies in which less than 70% of participants were male, compared to studies in which more than 70% of participants were male (Figure 7).

Discussion

This meta-analysis included 4 studies with 456 participants and compared several outcomes between patients who received empagliflozin and those who received placebo. The included studies exhibited a low risk of bias based on the revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) tool. Our findings showed that compared to placebo, empagliflozin significantly increased LVEF and markedly decreased LV end-diastolic volume, LV end-diastolic volume index, LV end-systolic volume, LV end-systolic volume index, and left atrial volume index; however, empagliflozin did not significantly affect LV mass and LV mass index. Similar to our study, Yan et al. conducted a meta-analysis and assessed the effect of empagliflozin on cardiac remodeling and functional capacity in patients with heart failure [16]. They found that empagliflozin significantly reduced LV end-diastolic volume and LV end-systolic volume and increase the 6-min walk distance [16]. Another meta-analysis of 7 clinical trials also revealed that treatment with empagliflozin significantly decreased the risk of cardiovascular death and hospitalization for worsening heart failure but did not significantly increase the 6-min walk distance [17]. A meta-analysis of patients with diabetes experiencing acute myocardial infarction indicated that treatment with empagliflozin significantly increased LVEF by 1.8% and decreased LV end-diastolic volume by –9.93 ml and LV end-systolic volume by –7.91 ml [18]. Using data from 15 clinical trials, Fan et al. assessed the effects of different SGLT-2 inhibitors on cardiac remodeling and reported that SGLT-2 inhibitors significantly increased LVEF (1.78%), LV end-systolic volume (–6.50 ml), left atrial volume index (–1.99 ml/m2), and left ventricular mass index (–2.38 g/m2); however, this study included participants regardless of having heart failure. In addition, the latter meta-analysis included all SGLT-2 inhibitors, not only empagliflozin [19].

Heart failure is characterized by distinct features in cardiac imaging modalities, such as echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [20]. In particular, left ventricular remodeling and hypertrophy and left atrial enlargement can be seen in a considerable proportion of patients, even before a significant decrease in LVEF [21]. Diastolic dysfunction was found to play a critical role in development of the signs and symptoms of heart failure and can help risk stratification, and provide prognostic data in patients with heart failure and impaired systolic function [20]. Furthermore, some features of cardiac remodeling, such as LV mass, were shown to significantly predict the clinical outcomes and prognosis of patients with heart failure [22, 23].

It has been found that cardiac remodeling in heart failure is accompanied by certain changes in the metabolism of cardiomyocytes [24, 25]. Specifically, a switch from fatty acid oxidation to glucose consumption has been observed in those with heart failure who exhibited cardiac remodeling in cardiac imaging [24, 25]. Since metabolic alterations of the myocardial tissue have been linked to cardiac remodeling and subsequent functional deficiencies and clinical symptoms, pharmacological interventions targeting cardiomyocyte energy metabolism in those with heart failure have been proposed as a promising therapeutic strategy [24, 26].

Empagliflozin, an anti-diabetic drug with beneficial metabolic effects, was found to enhance β-oxidation and ameliorate insulin resistance in those with early-stage type 2 diabetes [27]. Likewise, Gaborit et al. observed that treatment with empagliflozin enhances plasma ketone body levels in individuals with type 2 diabetes, suggesting an alteration in cardiac energetics [28]. Consistently, empagliflozin was reported to enhance myocardial work efficiency and reverse adverse myocardial remodeling after myocardial infarction in pigs by promoting myocardial consumption of free fatty acids and branched-chain amino acids, increasing myocardial adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels, and lowering myocardial glucose consumption [29]. Similarly, other animal studies have demonstrated that empagliflozin restores mitochondrial function during myocardial remodeling, thereby potentiating fatty acid oxidation pathway-dependent respiration and decelerating adverse myocardial remodeling [30–32]. Moreover, empagliflozin-mediated modulation of myocardial energy metabolism and mitochondrial function was observed to suppress oxidative stress and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes, thereby preventing further cardiomyocyte loss in diabetic cardiomyopathy [33].

Building upon data from 4 recent clinical trials, this meta-analysis indicated that compared to placebo, empagliflozin can significantly improve myocardial function, evidenced by increased LVEF, and reverse some features of myocardial remodeling, such as increased LV end-diastolic volume, LV end-systolic volume, and left atrial volume index, but failed to reduce LV mass.

We found that compared to placebo, empagliflozin led to a 2.96% increase in LVEF among those with heart failure over 3–9 months of treatment. These imaging findings are consistent with the clinical findings that treatment with empagliflozin can improve the functional status of patients with heart failure and reduce cardiovascular death or hospitalization for worsening heart failure [16, 17]. Although there was not a huge increase in LVEF or the decrease in LV mass was not statistically significant, such changes are still clinically promising, since they have been achieved over only 3–9 months of treatment, and greater improvements can be expected with prolonged treatment. Furthermore, these minor changes in cardiac function and structure were associated with marked improvement in clinical outcomes.

There are several limitations to our study. First, fewer than 10 studies were included in this meta-analysis; therefore, we could not perform subgroup analysis and meta-regression. Second, a high degree of statistical heterogeneity was observed for most outcomes, potentially affecting the accuracy of the results. However, we employed a random-effects model to overcome heterogeneity among studies. Third, there were some methodological differences among studies; however, degrees of methodological differences are commonly observed among studies included in a meta-analysis, and the methodological differences observed in this meta-analysis were minor. Future clinical trials are encouraged to provide more data and validate our findings.

Conclusions

Compared to placebo, empagliflozin 10 (mg/day) significantly increased LVEF, decreased LV end-diastolic volume, LV end-diastolic volume index, LV end-systolic volume, LV end-systolic volume index, and left atrial volume index, but did not significantly change LV mass and LV mass index. These findings suggest that empagliflozin can reverse cardiac remodeling in heart failure, which is of great importance for the design of future practice guidelines.