Introduction

Since primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has been a method of choice and standard of care from many years, this method recently received more attention from researchers in the field of intervention and treatment for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) [1]. About 500,000 cases of STEMI have been reported annually, which accounts for 30–40% of cardiovascular diseases [2]. Reperfusion damage that sometimes occurs after recanalization can disrupt myocardial blood circulation and subsequently cause several serious clinical problems; therefore, the importance of the primary percutaneous coronary intervention method and the evaluation of all aspects of it have become necessary and logical [3]. Nicorandil (2-nicotinamidoethyl-nitrate ester) is a compound containing nitrate with two specific functions. The first is the donation of nitric oxide, which causes dilatation of the coronary arteries of the heart and, in particular, improves and increases microcirculation; therefore, it can ameliorate coronary blood flow. In its second function, due to its sensitivity to adenosine triphosphate, it causes the opening of potassium channels in vascular smooth muscles with its agonistic role [3, 4]. According to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), one of the main causes of death worldwide is coronary heart disease, the most well-known symptoms of which are narrowing of blood vessels and subsequent reduction or stoppage of blood flow [5]. Many studies have presented results that show that the administration of nicorandil, in addition to reducing the mortality of patients, significantly reduces chest pain and re-hospitalization as well as the duration of hospitalization of patients [5]. One of the most dangerous and serious types of cardiovascular diseases is the acute type of STEMI, which is caused by the blockage of one or more coronary arteries of the heart, and statistically, it accounts for a significant number of hospital emergency cases [2]. Based on recent guidelines, the golden time for primary PCI is within 2 h after the diagnosis of MI, and the best time for routine PCI is 24 h after the diagnosis of MI [6]. The PCI treatment strategy is due to the rapid ability to re-canalize the vessels, which significantly reduces the size of the infarct and its clinical consequences. As a therapeutic strategy of blood reperfusion, it is known as a logical and practical method [2].

Considering that nicorandil is administered orally and intravenously for cardiovascular patients, and the hypothesis of a greater and direct effect of nicorandil in the case of intracoronary administration, in this study, we examined some of the more important clinical outcomes evaluated in recently published randomized controlled trial (RCT) studies in our meta-analysis.

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis by searching the following databases from inception to October 6, 2024: PubMed, Web of Sciences, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library. The keywords used for this study were: “Nicorandil” AND (“Percutaneous Coronary Intervention” OR “PCI”) AND (“ST elevation” OR “ST-segment elevation” OR “ST segment elevation” OR “STEMI”) AND (“clinical trial” OR “randomized controlled trial”). Our search strategy is detailed in the Supplementary Material File. In addition, to identify and include all related studies, we checked the reference lists of clinical trials and previous reviews. All retrieved studies were transferred to Endnote 9 reference manager software to remove duplicates. The protocol of this study is registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024591971). We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to complete this meta-analysis (Supplementary Material S1).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) being a randomized controlled trial or clinical trial; (2) including patients with STEMI undergoing PCI; (3) nicorandil was used without the concomitant use of other drugs.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) non-English studies; (2) study designs other than randomized controlled trials or clinical trials; (3) nicorandil was administered alongside other drugs as part of the treatment.

Data extraction and outcome measures

Screening of the title and abstract of all retrieved articles was performed by two researchers, Mingying Gu and Tingting Xu, to scrutinize the exact relevance of each to the topic; irrelevant articles were subsequently omitted. The full text of the remaining articles was assessed by two researchers to ensure their full compliance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All discordance and inconsistencies were resolved through consultation and discussion.

Data collection in this study included the following: basic characteristics of patients, such as age, gender, blood pressure, diabetes; and study characteristics such as: sample size, ethnicity, country of publication, and year of publication. Outcomes in this project included measures of chest pain, arrhythmia, heart failure, cardiovascular death, re-hospitalization and coronary blood flow.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Estimated treatment differences with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for heart failure, cardiovascular death, re-hospitalization, coronary blood flow, arrhythmia, and chest pain were collected from original studies. For studies whose estimated treatment differences and 95% CI were not reported, these statistics were computed using the number of events and non-events and the pooling process for each outcome group in all studies included in our meta-analysis. Standard error (SE) and CI were converted to one another using the formulas mentioned in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.3. The meta-analysis was conducted using a random-effects model (Der-Simonian-Laird) in Stata version 14.0 (StataCorp, TX, USA). The I2 statistic was used to determine heterogeneity between studies. In the presence of significant heterogeneity (I2 > 50%), we adopted a random-effects model; otherwise, we adopted a fixed-effects model.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was conducted to identify studies causing heterogeneity and investigate whether the exclusion of individual studies could significantly undermine the robustness of the results.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses were conducted based on the dose of nicorandil, age of patients, and treatment intervention types in the nicorandil group to assess the effect of intracoronary nicorandil treatment on different subgroups of patients and identify the source of heterogeneity (Supplementary Material S2).

Results

Search results

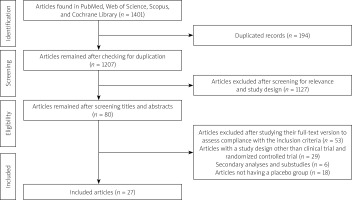

We utilized the aforementioned search strategy and first gathered 166 articles from PubMed, 1019 from Scopus, 184 from Web of Science, and 32 from Cochrane Library. Of the 1401 articles, 194 were removed due to duplication, leaving 1207. After screening the titles and abstracts, 1127 articles were excluded due to lack of relevance. The full-text version of 80 articles was screened to assess their compliance with the inclusion criteria, among which 27 studies were included (Table I, Figure 1). In total, 1802 participants in the control group and 1844 participants in the nicorandil group were included in this study.

Table I

Characteristics of included studies

Results of meta-analysis

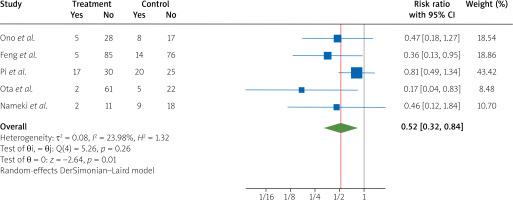

After pooling the data about the arrhythmia outcome of five randomized controlled trials [4, 7–10], we found a significant effect of treatment with nicorandil during PCI compared to the control group, which showed a decrease in arrhythmia in patients with STEMI (RR = 0.52, 95% CI [0.32, 0.84], I2 = 23.98%) (Figure 2).

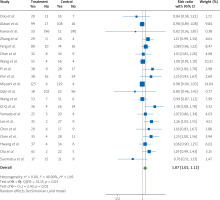

The pooled data from twenty RCTs [1, 7–9, 11–26] indicate a significant effect of nicorandil treatment during PCI on patients with STEMI regarding the increase in coronary blood flow compared to the control groups at the end of the follow-up (RR = 1.07, 95% CI [1.01, 1.12], I2 = 40.90%) (Figure 3).

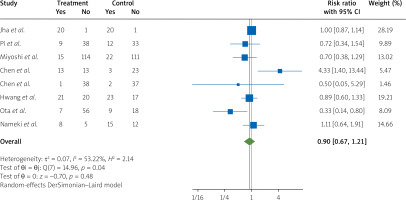

By pooling the data from eight RCTs [9, 10, 17, 25, 27–30] on the outcome of chest pain presence in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI, we found that nicorandil treatment compared to the control groups did not significantly lower the risk of chest pain among the patients (RR = 0.90, 95% CI [0.67, 1.21], I2 = 53.22%) (Figure 4).

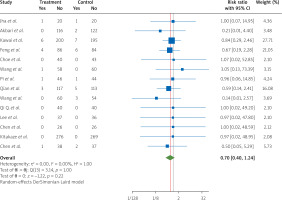

Data on cardiovascular death, as an important outcome from 14 RCTs [4, 7, 12, 14, 15, 19, 20, 22, 24, 27, 31–34], showed that treatment with nicorandil for STEMI patients undergoing PCI, compared to patients in the control groups, did not lower the occurrence of CVD during hospitalization (RR = 0.70, 95% CI [0.40, 1.24], I2 = 0.00%) (Figure 5).

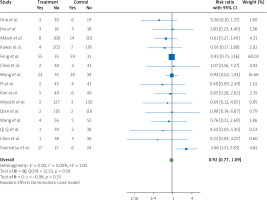

New heart failure event data from 15 RCTs [4, 7, 8, 11, 12, 14–17, 19, 20, 24, 26, 27, 35] clarified that treatment with nicorandil, compared to control group patients with STEMI who underwent PCI, has no significant effect in lowering the risk of this important outcome at the end of the procedure (RR = 0.92, 95% CI [0.77, 1.09], I2 = 0.00%) (Figure 6).

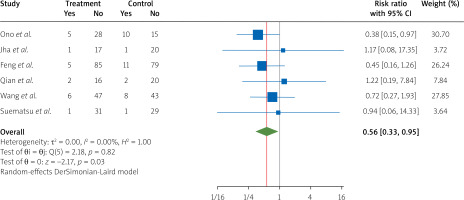

After pooling the data from six RCTs [4, 8, 15, 26, 27, 33] on the re-hospitalization risk, we concluded that treatment with nicorandil during PCI in STEMI patients compared to the control group significantly reduced the re-hospitalization risk (RR = 0.56, 95% CI [0.33, 0.95], I2 = 0.00%) (Figure 7).

Due to significant heterogeneity, a random-effects model, and Der-Simonian-Laird model were adopted.

Sensitivity analysis

Using the sensitivity analysis clearly shows the independence of the overall result of the study from the individual studies’ effects; therefore, omitting each individual study did not change the final result of our study. In this regard, we evaluated several outcomes as follows: 1) the chest pain result is robust after implementing the sensitivity test (leave-one-out) on its data, and nicorandil treatment during the PCI procedure still failed to reduce the patient’s chest pain risk; 2) The sensitivity analysis on cardiovascular death indicates no changes in the final result of this outcome after the omission of any individual studies one by one. 3) Similarly, the sensitivity analysis revealed that the overall result of the study regarding the effect of nicorandil on STEMI patients was independent of individual studies, and removing individual studies did not change the result for heart failure incidence. 4) As the final outcome, the coronary blood flow rate in the nicorandil group compared to the control group, when implementing the leave-one-out test, had no effect and induced no change in the overall result of this important outcome as well (Supplementary Material S3).

Subgroup analysis

In our study, the subgroup analyses were conducted based on the age of patients, intervention types, and the dose of nicorandil, to assess the effect of nicorandil treatment on STEMI patients during the PCI procedure in different subgroups of patients and identify the source of heterogeneity.

By conducting a subgroup analysis for cardiovascular death events, in terms of nicorandil dose, there was no difference between the two subgroups of 2 mg or less (RR = 0.70, 95% CI [0.27, 1.81], I2 = 0.00%) and more than 2 mg (RR = 0.66, 95% CI [0.32, 1.35], I2 = 0.00%). In addition, evaluating the condition of the treatment intervention types (orally (RR = 0.17, 95% CI [0.02, 1.39], I2 = 0.00%)/intravenous (RR = 0.82, 95% CI [0.37, 1.83], I2 = 0.00%)/intracoronary (RR = 0.71, 95% CI [0.28, 1.79], I2 = 0.00%)/intravenous + intracoronary (RR = 1.02, 95% CI [0.11, 9.44], I2 = 0.00%), the cardiovascular death outcome shows no difference between different subgroups. Heart failure event outcomes after assessment in the different dose subgroups (2 mg or less (RR = 0.99, 95% CI [0.80, 1.23], I2 = 60.42%)/more than 2 mg (RR = 0.67, 95% CI [0.44, 1.01], I2 = 0.00%) indicate no significant change in the overall result. Heart failure events in different age subgroups (less than 60 years (RR = 0.90, 95% CI [0.75, 1.08], I2 = 0.00%)/more than 60 years (RR = 1.07, 95% CI [0.64, 1.77], I2 = 50.13%), and in different treatment intervention types (orally (RR = 0.65, 95% CI [0.33, 1.31], I2 = 0.00%)/Intravenous (RR = 1.01, 95% CI [0.73, 1.41], I2 = 45.96%)/intracoronary (RR = 0.91, 95% CI [0.73, 1.12], I2 = 0.00%)/intravenous + intracoronary (RR = 1.03, 95% CI [0.32, 3.31], I2 = 0.00%)) as another subgroup division shows no difference between different subgroups. The computation of the data results for coronary blood flow, as another important clinical outcome, revealed no significant difference between the two different age subgroups (less than 60 years (RR = 1.03, 95% CI [0.98, 1.09], I2 = 31.46%)/more than 60 years (RR = 1.03, 95% CI [0.98, 1.07], I2 = 52.47%). Moreover, subgroup analysis of the two different nicorandil doses (2 mg or less (RR = 1.14, 95% CI [1.07, 1.23], I2 = 21.93%)/more than 2 mg (RR = 1.00, 95% CI [0.97, 1.04], I2 = 17.36%), for coronary blood flow outcome shows no significant difference between the two different subgroups. The last subgroup analysis for coronary blood flow outcome, on the various treatment intervention types (orally (RR = 0.98, 95% CI [0.91, 1.06], I2 = 0.00%)/intravenous (RR = 0.98, 95% CI [0.94, 1.02], I2 = 0.00%)/intracoronary (RR = 1.16, 95% CI [1.09, 1.24], I2 = 0.00%)/intravenous + intracoronary (RR = 1.10, 95% CI [0.98, 1.24], I2 = 0.00%)), showed that from four subgroups, three of them had no significant difference; only one subgroup, regarding the intracoronary treatment intervention type, showed a significant effect (Supplementary Material S2).

Publication bias

Based on visual inspection, the funnel plot was approximately asymmetric for arrhythmia, chest pain, heart failure, cardiovascular death, coronary blood flow, and re-hospitalization. In addition, Egger’s test and Begg’s test showed no publication bias for the aforementioned measured clinical outcomes: arrhythmia (p-value = 0.035 and p-value = 0.462, respectively); chest pain (p-value = 0.919 and p-value = 0.536, respectively); heart failure (p-value = 0.296 and p-value = 0.276, respectively); cardiovascular death (p-value = 0.946 and p-value = 0.912, respectively); coronary blood flow (p-value = 0.383 and p-value = 0.721, respectively); and re-hospitalization (p-value = 0.299 and p-value = 0.707, respectively) (Supplementary Materials S4 and S5).

Discussion

This study is a comprehensive and updated review and meta-analysis of the effects of nicorandil on STEMI patients.

In this meta-analysis study, we included 27 RCTs and clinical trials. The number of patients who participated in the project was 3646, and we detected some positive effects of nicorandil on several aspects of complications and clinical outcomes in patients with STEMI. The results of the study indicate that nicorandil reduced re-hospitalization due to STEMI and significantly increased coronary blood flow after intervention during the PCI process and treatment of patients. Arrhythmia incidence, after comparison of the nicorandil and control groups, shows the significant effect of nicorandil in its reduction. In addition, chest pain, heart failure, and cardiovascular death events were not significantly reduced in patients after admission to the hospital and undergoing the PCI procedure.

Clinical outcome results in our study, compared to previous studies, bring forward some points worth noting. According to Borja et al., the rapid use of β-blockers during the PCI process reduces arrhythmia; however, this beneficial effect of β-blocker drugs with long-term use is not confirmed. This issue confirms and highlights the positive effect of using nicorandil for STEMI patients who experience cardiac arrhythmia, and it aligns with the results of our study [6, 36–38]. Ji et al. in one study clearly expressed that nicorandil use in STEMI patients leads to an increase in the coronary blood flow rate, similar to our results. Another study conducted by Akiyoshi et al. compared the use of nicorandil and verapamil during the PCI procedure regarding coronary blood flow outcomes in STEMI patients, showing the advantages of nicorandil over verapamil in improving coronary blood flow rate [39]. Li et al. reported a decrease in re-hospitalization in STEMI patients using nicorandil during the PCI treatment process, supporting our similar findings in this regard [40]. Zhou et al.’s study on heart failure rate reduction revealed a significant effect of nicorandil treatment during PCI in STEMI patients, which contrasts with our finding of no significant effect of nicorandil treatment on patients undergoing PCI in lowering this rate. Moreover, their findings regarding the incidence of cardiovascular death in the control and nicorandil-treated groups, like our results, did not show a significant effect of nicorandil treatment when comparing all-cause death between their evaluated groups [41]. Pi et al. reported lower chest pain incidence in the nicorandil treatment group compared to the control group in their last study, and while our results revealed similar findings, no significant effect was observed [7]. Based on our study results and other studies explaining the protective effect of nicorandil during PCI in STEMI patients, alongside several other positive effects of using nicorandil – such as its role in improving coronary blood flow rate, reducing myocardial infarction size, preventing myocardial ischaemia, and causing vasodilation in coronary arteries and peripheral veins – physicians and researchers must focus more on all clinical outcome aspects and effects of nicorandil in STEMI patients to achieve better clinical results.

Strengths

In our meta-analysis, we included high-quality randomized controlled trials and clinical studies with low publication bias. Our study is the most up-to-date meta-analysis that contains a large number of studies with many patients. Additionally, we implemented various subgroup analyses and performed sensitivity analysis to evaluate the factors associated with the effects of nicorandil on several clinical outcomes in patients with STEMI for better management of the future clinical trials.

Limitations

Our study has some limitations that should be addressed. First, there was heterogeneity between the included studies; thus, we used a random-effects model. To identify the source of heterogeneity, we implemented several subgroup analyses and the funnel plot test. Second, some variables, such as body weight or BMI change, were not reported by all original studies. Third, clinical trials reported some variables, such as baseline BMI and baseline cardiovascular risks, differently; therefore, we omitted those baselines from our study.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis revealed that nicorandil can lead to a clinically and statistically significant decrease in arrhythmia, and re-hospitalization of patients. Additionally, nicorandil treatment during the PCI process shows no significant effect on decreasing chest pain, heart failure, and cardiovascular death, and revealed no significant effect on increasing the coronary blood flow rate between the different patient groups.