Introduction

Hypertension is a common cardiovascular disease and public health problem, which can lead to cardiovascular remodeling, end-organ damage, and premature death if insufficiently treated [1]. For instance, in 2010, 31.1% of adults (1.39 billion) globally were estimated to be affected by hypertension, with a higher prevalence in low-income and middle-income countries [2]. In addition, from 1990 to 2019, the global prevalence of hypertensive heart disease increased by 138%, and the disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) associated with hypertensive heart disease rose by 154% [3].

Sedentary lifestyle has been identified as an independent predictor of cardiovascular diseases [4]. Consistently, previous reports have shown an inverse correlation between physical activity and the incidence of cardiovascular diseases [5]. Lifestyle modification has long been recommended in the management of hypertension, and physical activity and exercise training have received much attention in this regard [6]. However, there are several types of exercise training, such as strength training, resistance training, and aerobic exercise, each one with its specific effects on blood pressure [7]. Recently, a considerable number of randomized controlled trials have assessed the effects of resistance exercise on the management of hypertension [8–12]. Some of these clinical trials reported that resistance training cannot significantly lower blood pressure in those with hypertension [8–10], while others reported a significant reduction in blood pressure after several weeks of resistance exercise [11–14]. Furthermore, the extent of the effect greatly varied among previous clinical trials reporting a significant effect [11–14].

Due to significant differences in the results of existing clinical trials in this field, it is impossible to draw a clear conclusion. Therefore, this meta-analysis was conducted to pool data from clinical trials and compare the effect of resistance training with that of control intervention on systolic and diastolic blood pressure among individuals with hypertension.

Aim

We aimed to identify the potential factors that can predict in which subgroups of patients resistance training can be more effective in the management of hypertension.

Method

Search strategy

We searched the Web of Science, The Cochrane Library, Scopus, and PubMed from inception to December 18, 2024. The search keywords were as follows: “Hypertension” AND (“Resistance Training” OR “Resistance Exercise” OR “Resistance Activity”).

The exact search strategy is presented in Supplementary Material 1. Furthermore, we searched the reference list of the identified trials or recent reviews to retrieve more randomized controlled trials. The identified trials were transferred to EndNote 9.0 and duplicates were deleted. We registered the protocol of this study in PROSPERO (CRD42024628558). This study strictly conformed to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [15].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) study design being a randomized controlled trial; (II) comparing the effect of resistance training with a control group on blood pressure; (III) only including patients with hypertension; and (IV) reporting at least one of the following efficacy outcomes: systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) study design being a case report, observational study, or review article; (II) including individuals without hypertension; (III) not reporting the target outcomes; and (IV) resistance training was combined with other interventions.

Data extraction and outcome measures

The literature was searched by two authors who independently screened the eligibility of all retrieved studies. All discrepancies were solved through consultation. The authors first evaluated the relevance of the articles and measured their compliance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria based on the titles and abstracts of the identified papers. Thereafter, the full-text version of the remaining articles was evaluated to determine their eligibility for inclusion.

The following data were collected: study characteristics (publication year, first author name, country of study, study design and settings), population (sample size, BMI, sex, and age), interventions (length of training), and outcomes (systolic and diastolic blood pressure).

Risk-of-bias assessment

The risk of bias for all studies was independently assessed by two researchers, and all discrepancies were solved via discussion. We used the revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) to determine the risk of bias for the included studies. The tool measures the risk of bias based on the randomization process, outcome measurement, missing outcome data, deviations from intended interventions, and selection of the reported results, providing an overall risk of bias for the included studies. All domains were assigned one of the following ranks: some concerns, low risk of bias, and high risk of bias [16].

Statistical analysis

To pool data from different studies, we extracted the number of participants in each group and mean changes and SD changes for systolic and diastolic blood pressure. A random-effects model (DerSimonian-Laird) was adopted to pool data. We performed this meta-analysis using Stata version 17.0 (StataCorp, TX, USA). The χ2 test and I2 statistic were employed to determine between-trial heterogeneity, and I2 more than 50% was deemed high statistical heterogeneity in this study.

Subgroup analysis

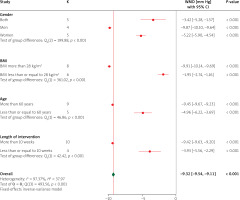

Subgroup analysis was conducted based on age (more than 60 years and equal to or less than 60 years), gender (males, females, and both), length of intervention (more than 10 weeks or less than or equal to 10 weeks), and baseline BMI (more than 28 kg/m2and less than or equal to 28 kg/m2) to identify the factors leading to between-trial heterogeneity and determine the factors associated with the beneficial effects of resistance training on hypertension.

Sensitivity analysis

Using the leave-one-out test, sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the robustness of our findings.

Publication bias

A funnel plot was drawn to visually assess the risk of publication bias. In addition, Begg’s test was conducted to determine the risk of publication bias. In the presence of significant publication bias, the trim-and-fill test was conducted to calculate the predicted effect size when more studies could be added.

Results

Systematic search results

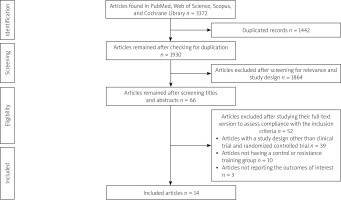

We identified 895 records from Web of Science, 394 records from PubMed, 1530 records from Scopus, and 553 records from the Cochrane Library. Of 3372 articles, 1442 duplicates were deleted and 1930 articles remained. After screening the titles and abstracts, 1864 articles were deleted because of irrelevance or incompliance with the inclusion criteria. Finally, the full text of the 66 remaining articles was assessed to determine their compliance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, 14 articles with 353 participants in the control group and 323 participants in the resistance training group were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis [8–14, 17–23] (Figure 1, Table I). Most of the studies were published between 2020 and 2024, demonstrating the importance of the topic as a current research hotspot. The majority of studies were from Brazil; however, there were some studies from Iran, Ethiopia, Japan, the United States, and South Korea. Abrahin et al. [17, 18], Banks et al. [10], Boeno et al. [20], and de Oliveira et al. [9] included both males and females, but other studies only included males or females (Table I). The length of intervention ranged from 8 to 16 weeks across studies, but most studies adopted 12 weeks as the length of intervention. The mean age of participants ranged from 45.72 years to 71.3 years across studies. Most studies included overweight and obese patients. The sample size of the included trials was generally small, and there was no study with more than 47 participants in each arm (Table I).

Table I

Characteristics of the included studies

| First author name | Publication year | Age [years] mean | Country of study | Gender | BMI [kg/m2] | Length of training [weeks] | Number of participants in the control group | Number of participants in the resistance training group | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abrahin et al. | 2022 | 66.5 | Brazil | Both | 27.9 | 12 | 21 | 20 | [17] |

| Abrahin et al. | 2024 | 66.6 | Brazil | Both | 28.4 | 12 | 25 | 27 | [18] |

| Alemayehu et al. | 2023 | 45.72 | Ethiopia | Males | 27.66 | 12 | 12 | 11 | [19] |

| Banks et al. | 2024 | 53.5 | United States | Both | 28.05 | 9 | 13 | 13 | [10] |

| Boeno et al. | 2020 | 45.5 | Brazil | Both | 33.25 | 12 | 12 | 15 | [20] |

| de Oliveira et al. | 2020 | 62.8 | Brazil | Both | 27.7 | 8 | 10 | 13 | [9] |

| dos Santos et al. | 2014 | 63.6 | Brazil | Females | 28.4 | 16 | 20 | 20 | [14] |

| Fecchio et al. | 2023 | 53 | Brazil | Males | 29.1 | 10 | 16 | 16 | [21] |

| Gonçalves et al. | 2014 | 65.9 | Brazil | Females | 27.5 | 12 | 10 | 7 | [8] |

| Hooshmand- | |||||||||

| Moghadam et al. | 2021 | 62.9 | Iran | Males | 28.3 | 12 | 12 | 12 | [22] |

| Miura et al. | 2015 | 71.3 | Japan | Females | 24.5 | 12 | 47 | 45 | [23] |

| Mota et al. | 2013 | 67.2 | Brazil | Females | 28.6 | 16 | 32 | 32 | [11] |

| Silva de Sousa et al. | 2024 | 53.5 | Brazil | Males | 29.6 | 10 | 15 | 15 | [12] |

| Son et al. | 2020 | 67.6 | South Korea | Females | 26.7 | 12 | 10 | 10 | [13] |

Risk-of-bias assessment

Considering the open-label design of a considerable proportion of randomized controlled trials included in this meta-analysis, the revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) indicated a high risk of bias for such studies (Supplementary material 2).

Meta-analysis

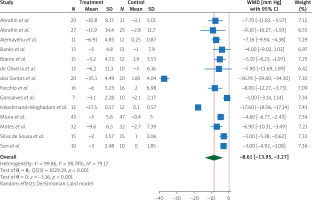

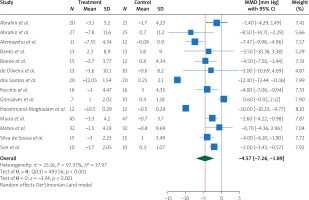

Pooling data from 14 randomized controlled trials [8–14, 17–23], we found that, compared to the control group, resistance training significantly decreased both systolic blood pressure (WMD = –8.61 mm Hg, 95% CI (–13.95, –3.27), I2 = 98.74%) and diastolic blood pressure (WMD = –4.57 mm Hg, 95% CI (–7.26, –1.89), I2 = 97.37%) (Figures 2 and 3); however, we found a significant degree of heterogeneity among the included trials and adopted a random-effects model to overcome this heterogeneity.

Subgroup analysis

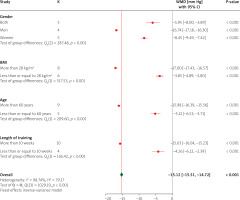

For both systolic and diastolic blood pressure, we found that the beneficial effects of resistance training were greater among men, those with a BMI more than 28 kg/m2, those aged more than 60 years, and those exercising for more than 10 weeks. Subgroup analysis suggested that these factors might lead to high heterogeneity and their optimization may enhance the beneficial effects of resistance training on hypertension (Figures 4 and 5).

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis revealed that removing the included studies one by one did not change the overall results of this meta-analysis, and the results remained stable (Supplementary Material 3).

Publication bias

Funnel plots showed a high degree of asymmetry for both systolic and diastolic blood pressure; thus, we conducted Begg’s test, which also indicated significant publication bias (p = 0.049 for systolic blood pressure and p = 0.381 for diastolic blood pressure) (Supplementary Material 4). Subsequently, we conducted the fill-and-trim test to calculate the estimated effect sizes if an adequate number of studies were available. The test indicated that if 4 more studies were available for systolic blood pressure, the effect size would be: WMD –11.04 mm Hg, 95% CI (–15.13, –6.95). The test also showed that if 2 more studies were available for diastolic blood pressure, the effect size would be: WMD –5.39 mm Hg, 95% CI (–7.74, –3.03).

Discussion

This meta-analysis pooled data from 14 randomized controlled trials with 676 patients with hypertension and found that, compared to the control group, resistance training significantly decreased both systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure. The beneficial effects of resistance training on blood pressure control were greater in men, those aged more than 60 years, those with BMI > 28 kg/m2, and after 10 weeks of intervention.

Since exercise training has shown promising effects on blood pressure control in individuals with hypertension in the last decades [24], recent clinical trials have increasingly investigated the effects of different modalities of exercise, such as aerobic exercise, resistance training, strength training, moderate-intensity training, high-intensity training, etc., on blood pressure, aiming to determine the most effective modality of physical activity for those with hypertension [25]. Consistently, a large proportion of the studies included in this meta-analysis were published between 2020 and 2024, suggesting the increasing importance of this topic in recent years. Our results indicated that, compared to the control group, resistance exercise led to a 8.61 mm Hg decrease in systolic blood pressure and 4.57 mm Hg decrease in diastolic blood pressure, which is much higher than that reported in a recent meta-analysis of clinical trials assessing the effects of aerobic exercise on systolic and diastolic blood pressure (1.78 and 1.23 mm Hg, respectively) [26]. These findings suggest the superiority of resistance training over aerobic exercise in reducing blood pressure in those with hypertension, although head-to-head analyses are needed to confirm this conclusion.

Interestingly, we found that higher BMI is associated with greater benefits of resistance training among those with hypertension. Since high BMI and obesity are well-known risk factors for hypertension and exercise can facilitate weight loss, it is rational to achieve superior weight-lowering effects in those with high BMI [27, 28]. Hence, this specific subgroup of patients must be motivated to conduct regular resistance exercise.

We also found that a longer course of resistance training can provide more robust benefits compared to a shorter course of resistance training. Since exercise can gradually enhance angiogenesis and partly reverse adverse cardiovascular remodeling, it can be expected that a longer course of resistance training can more effectively attenuate adverse cardiovascular remodeling and provide greater clinical benefits [29, 30].

In subgroup analysis, it was found that resistance training is more beneficial in those aged more than 60 years than in younger individuals. Since older individuals are more likely to have a sedentary lifestyle [31], adopting regular resistance training may make a greater difference in their physical activity. Taken together, subgroup analysis indicated that resistance training can offer a larger decrease in blood pressure in those with a greater need for physical activity. These findings hold significance for the design of future practice guidelines and can help optimize lifestyle modification for those with hypertension.

There are several limitations to our study. First, since a considerable number of studies were open-label, the risk of bias was high in these studies, potentially affecting the accuracy of their results. Second, there was a high degree of heterogeneity among the included studies; therefore, we adopted a random-effects model to conduct this meta-analysis. We also conducted a subgroup analysis to identify the potential sources of heterogeneity. In addition, we conducted sensitivity analysis to investigate whether removing individual studies would affect the overall results. Third, we detected a high risk of publication bias, which necessitates more studies in this field; however, the fill-and-trim test revealed that even with more studies, the results would remain significant and the effect size is likely to become even larger. Fourth, most clinical trials were conducted in Brazil; thus, our findings cannot be generalized to all regions and countries, and additional studies are needed from other countries to enhance the generalizability of our findings. Fifth, a small number of studies were included in this meta-analysis, particularly because each clinical trial included a small number of patients. Future clinical trials are encouraged to provide more data and validate our findings.

Conclusions

In this meta-analysis, we pooled data from 14 randomized controlled trials with 676 patients with hypertension and found that, compared to the control group, resistance training significantly decreased both systolic blood pressure (WMD = –8.61 mm Hg, 95% CI (–13.95, –3.27), I2 = 98.74%) and diastolic blood pressure (WMD = –4.57 mm Hg, 95% CI (–7.26, –1.89), I2 = 97.37%). The beneficial effects of resistance training on blood pressure control were more prominent in men, those aged more than 60 years, those with BMI > 28 kg/m2, and after longer intervention. These findings hold significant implications for the design of future guidelines.