Summary

Our study examines the relationship between long-term residence at moderate altitude and coronary artery disease (CAD) severity. While the impact of altitude on cardiovascular health has been studied, its direct effect on CAD severity remains unclear. We found that living at moderate altitude is independently associated with higher SYNTAX scores in non-STEMI patients, alongside hypertension, elevated low-density lipoprotein levels, and reduced ejection fraction. These findings highlight the potential role of altitude-related factors in CAD progression, emphasizing the need for further research to explore underlying mechanisms and clinical implications.

Introduction

Ischemic heart disease, also referred to as coronary heart disease, is the leading cause of mortality worldwide [1]. Despite significant advances in follow-up care, pharmacological treatments, and reperfusion strategies, it continues to pose a major public health challenge. Numerous clinical conditions, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, smoking, advanced age, air pollution, dietary behaviors, and a sedentary lifestyle, have been identified as etiological risk factors for coronary artery disease (CAD) [2, 3]. These risk factors play a critical role in preventing future cardiovascular events.

The SYNTAX (Synergy between PCI with Taxus and Cardiac Surgery) score, introduced by Sianos et al. in 2005, is a scoring system designed to assess the severity of CAD [4]. It is calculated using data from a patient’s coronary angiogram, evaluating the entire major coronary anatomy while considering arterial dominance. Higher SYNTAX scores are associated with more complex treatment needs and higher mortality rates [4, 5].

Globally, mountain regions encompass approximately 24% of the Earth’s surface, with populations residing at varying altitudes [6]. Altitude is generally classified into moderate altitude (1500–2500 m), high altitude (2500–3500 m), and very high altitude (> 3500 m), with an estimated 400 million people permanently living at altitudes above 1500 m [7, 8]. While high altitudes are characterized by increased ultraviolet radiation and reduced oxygen (atmospheric) pressure, temperature, and humidity, the long-term effects of these environmental factors on the cardiovascular system remain incompletely understood.

Several studies have suggested that higher altitudes are associated with lower CAD mortality rates [9, 10]. Conversely, other studies indicate that prolonged exposure to high altitudes may elevate the risk of stroke, mortality, and acute coronary syndrome, thereby representing potential risk factors for adverse cardiovascular events [11–14]. Although the impact of acute high-altitude exposure on patients with cardiovascular disease has been studied, there is lack of research specifically examining the relationship between long-term residence at higher altitudes and CAD severity.

Aim

This study aims to investigate the relationship between the severity of coronary artery disease and long-term residence at moderate altitudes.

Material and methods

Study design and patient population

This retrospective study included patients aged 18 years and older who were diagnosed with de novo non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (non-STEMI) and admitted to healthcare centers located at different altitudes in Turkiye – a low-altitude center (Ataturk State Hospital, Izmir, 70 m) and a moderate-altitude center (Mus State Hospital, Mus, 1690 m) – between January 2023 and December 2023. Patients were grouped based on their living altitude. Only NSTEMI patients were included to ensure a more reliable assessment of coronary lesion complexity using the SYNTAX score. In STEMI patients, acute thrombotic occlusions, dynamic changes in coronary flow, coronary vasospasm, and emergency revascularization procedures may alter lesion morphology, potentially leading to inaccuracies in SYNTAX score calculation. To ensure sufficient chronic exposure, only patients who had been living at a moderate altitude for at least 6 months were included. They were also asked about any travel to cities at different altitudes within the 6 months preceding the index procedure to confirm sustained residence at their respective altitude. This duration was chosen based on prior evidence indicating that while initial physiological adaptations to high altitude occur within weeks, long-term cardiovascular adaptations, including autonomic and hematological changes, may take several months to manifest [15].

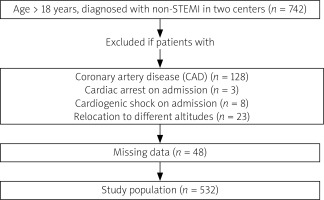

Patients with missing data, those not residing at the specified altitude for at least 6 months, and those with a prior history of coronary artery disease, cardiac arrest on admission, or cardiogenic shock on admission were excluded from the study (Figure 1).

Definitions

Non-STEMI was defined according to the current ESC guidelines as acute chest discomfort accompanied by elevated troponin levels, without persistent ST segment elevation or its equivalents [16]. The diseased vessels were defined as the presence of a diameter stenosis exceeding 50% in major epicardial arteries. Coronary angiography was performed using a Siemens Artis floor angiography device (Siemens, Germany). Before the procedure, all patients received acetylsalicylic acid and unfractionated heparin at a dose of 70 U/kg. The SYNTAX score was calculated using the website www.syntaxscore.com [17] and assessed by two experienced interventional cardiologists.

Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study formula [18]. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as eGFR less than 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. Hypertension (HT) was determined by a prior diagnosis, systolic blood pressure above 140 mm Hg, or diastolic BP above 90 mm Hg. Diabetes mellitus (DM) was diagnosed based on patient history, fasting plasma glucose levels exceeding 126 mg/dl, random plasma glucose levels surpassing 200 mg/dl, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) values greater than 6.5%, or the use of anti-diabetic medications. During hospitalization, all patients underwent post-procedural transthoracic echocardiography within 24 h (Epiq 7; Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA, USA) Based on the literature, the groups were classified as low-altitude (below 1500 m) and moderate-altitude (above 1500 m) [8].

Data collection

The demographic characteristics of the patients (age, gender, and medical history), echocardiographic findings, angiographic findings, and laboratory values (including complete blood count, kidney and liver function tests) were retrospectively retrieved from the hospitals’ databases. Laboratory findings were evaluated using blood samples obtained in the emergency department before angiography and during the in-hospital follow-up period within 24 h. All patients were managed according to current guidelines and recommendations for the treatment of non-STEMI [16, 19].

Statistical analysis

Jamovi and R 4.3.2 software (Vienna, Austria) were used for statistical analysis. Continuous variables, which were determined to be non-normally distributed, are presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), while categorical variables are expressed as absolute values and percentages. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare independent continuous data between groups, and Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s exact test was used for comparisons of categorical data between groups.

In this study, to minimize bias and balance covariate distribution, inverse probability weighting (IPW), propensity score weighting, and doubly robust estimation were applied. Based on prior research and expert consensus, the following variables were chosen as covariates for logistic regression analysis to assess the impact on the outcome: altitude, age, sex, HT, DM, smoking, CKD, eGFR, hemoglobin (HB), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and body mass index (BMI). The probabilities derived from the model were utilized to compute stabilized inverse probability weights. These weights were subsequently applied to assess the impact of each individual’s contribution to both the SYNTAX score and the multiple linear regression model.

Baseline covariate balance between the low-altitude and moderate-altitude groups before and after propensity score weighting was evaluated using absolute standardized mean differences. Then, another regression model, including confounders such as age, sex, HT, DM, smoking, CKD, eGFR, HB, LDL, COPD, and BMI, was applied for double robustness. The model coefficients were reported as estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

For all statistical analyses, 2-tailed probability (p) values of less than 0.05 were deemed to indicate statistical significance.

Results

In this study, a total of 532 patients were included based on predefined eligibility criteria, with 309 patients in the low-altitude group and 223 patients in the moderate-altitude group. The median age of the patients was 64 (IQR: 56–70) years, and 71.6% were male. An evaluation of demographic, echocardiographic, and angiographic findings based on altitude revealed a significant difference in the SYNTAX score, which was higher in the moderate-altitude group, while no other significant differences were observed between the groups (Table I).

Table I

Demographic characteristics of patients according to their altitude

Regarding laboratory findings, hemoglobin (HB), hematocrit (HCT), and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels were significantly higher in the moderate-altitude group, whereas white blood cell (WBC) counts were lower (Table II).

Table II

Admission laboratory and angiographic findings of patients according to their altitude

[i] AST – aspartate aminotransferase, ALT – alanine aminotransferase, BUN – blood urea nitrogen, CR – creatinine, CRP – C-reactive protein, eGFR – estimated glomerular filtration rate, HB – hemoglobin, HCT – hematocrit, HDL – high-density lipoprotein, LDL – low-density lipoprotein, LYPMH – lymphocytes, NEU – neutrophils, PLT – platelets, Tot – total, WBC – white blood cells. *All variables are presented as median (Q1–Q3).

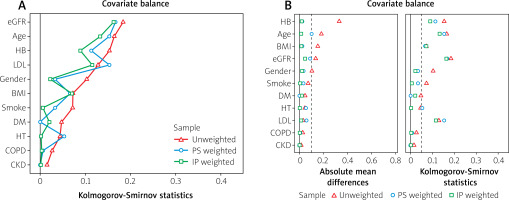

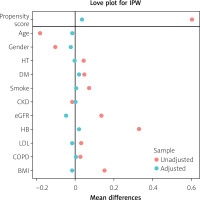

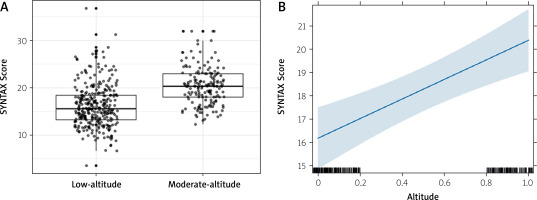

Propensity score analysis was performed to address potential differences in etiological factors between the groups. Inverse probability weighting yielded better results than matching and was therefore used in subsequent analyses (Figure 2). In the doubly robust IPW regression model, where age, sex, HT, DM, smoking, CKD, eGFR, HB, LDL, COPD, and BMI were balanced (Figure 3), living at a higher altitude was found to be an independent predictor of a higher SYNTAX score (estimate: 4.21, 95% CI: [2.34–6.08]; p < 0.001) (Figure 4).

Figure 2

Covariate balance before and after propensity score weighting. A – Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics showing baseline covariate balance before and after weighting. B – Absolute standardized mean differences for baseline covariates, demonstrating improved balance after propensity score weighting

Figure 3

Mean differences before and after propensity score adjustment. Mean differences for baseline covariates between low-altitude and moderate-altitude groups before and after propensity score adjustment. Adjusted covariates are closer to zero, indicating improved balance

Figure 4

Relationship between altitude and SYNTAX score. A – Boxplots comparing SYNTAX scores between patients living at low and moderate altitudes. B – Linear regression plot showing a positive association between altitude and SYNTAX score, with a shaded 95% confidence interval

Additionally, other independent predictors of a higher SYNTAX score in patients presenting with non-STEMI included LDL levels (estimate: 0.07, 95% CI: [0.04–0.10]; p < 0.001), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (estimate: –0.38, 95% CI: [–0.51–-0.24]; p < 0.001), HT (estimate: 2.51, 95% CI: [0.45–4.58]; p = 0.01), and age (estimate: 0.08, 95% CI: [-0.01–0.16]; p = 0.05) (Table III).

Table III

Inverse probability weighted model of multiple linear regression analysis

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, no prior study has investigated the relationship between altitude and CAD severity in patients with non-STEMI. Our findings indicate that living at moderate altitude, a history of HT, elevated LDL levels, lower LVEF, and smoking are associated with a higher SYNTAX score.

The impact of altitude on CAD remains unclear. Some studies suggest that CAD is less prevalent at higher altitudes due to a lower prevalence of traditional risk factors [20]. For instance, Mortimer et al. reported lower CAD mortality rates among men living at higher altitudes, attributing this to healthier lifestyles, including increased physical activity [11]. However, other researchers have argued that this explanation may not be sufficient. Over time, a global shift toward sedentary lifestyles and unhealthy eating habits has diminished the protective effects of altitude, especially at low and moderate altitudes, where modern habits are more easily adopted [9, 21].

Although the exact mechanisms behind our study’s findings cannot be fully explained, several hypotheses can be proposed. The primary physiological difference between altitudes lies in partial oxygen pressure, which decreases at higher altitudes. Acute exposure to high altitude is well recognized as a cardiac stressor [22, 23]. Studies have demonstrated that acute hypoxia increases heart rate, resulting in elevated cardiac output, although stroke volume remains nearly constant. Over time, cardiac output normalizes, but heart rate persists at higher levels [24, 25]. Similarly, Vogel et al. observed that individuals native to, or residing long-term at, higher altitudes exhibit higher heart rates and lower stroke volumes but maintain comparable cardiac output to sea-level controls at rest [26].

Regarding coronary circulation, hypoxia has been shown to increase coronary blood flow initially [27]. However, prolonged exposure to higher altitudes may reduce coronary blood flow [28]. Since coronary oxygen extraction is already high under normal conditions, myocardial hypoxia necessitates an increase in oxygen delivery. To achieve this, altitude-induced hypoxia triggers hormonal responses, including elevated erythropoietin and hemoglobin levels, which are critical for acclimatization and oxygen delivery. Despite balancing hemoglobin levels between groups in this study, the observed differences suggest additional mechanisms at play.

Chronic hypobaric environments induce adaptations in immune cells, such as lymphocytes and phagocytes, leading to stress-related events that elevate cytokine levels and disrupt the pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine balance [29, 30]. Hypoxia appears to play a central role in these processes, although the precise mechanisms of cytokine production remain unclear. High-altitude exposure has been linked to increased oxidative stress and cellular damage, which contribute to elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α [31, 32]. These cytokines can cause systemic inflammation, including increased heart rate, sympathetic tone, and metabolic changes. Moreover, they activate the atherosclerotic cascade by promoting leukocyte migration, LDL adhesion to the endothelium, and thrombogenicity [33].

Similarly, Kotwal et al. demonstrated that high altitude increases fibrinogen levels, platelet activation factors, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 levels, leading to a hypercoagulable state [34].

Although some studies have reported lower total cholesterol and LDL levels and higher HDL levels at high altitudes, the activities and effects of these lipids may vary under the influence of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Additionally, the erythropoiesis associated with altitude adaptation may elevate serum cholesterol levels [35–38]. Consequently, even with similar atherogenic factors across groups, enhanced atherosclerosis mediated by hypoxia-induced cytokine stimulation could result in more extensive CAD.

While our findings provide novel insights, further research is needed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the relationship between altitude and CAD severity. These results may inform future research design and highlight potential avenues for intervention.

Consistent with the literature, we found that higher LDL levels, smoking, a history of HT, and lower LVEF were associated with higher SYNTAX scores [39, 40].

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, as a retrospective study, its findings should be interpreted in the light of the common limitations of retrospective studies. Second, the relatively small sample size and the inclusion of only two centers at different altitudes may have influenced the results. Additionally, we were unable to assess correlations across a broader range of altitudes, limiting the generalizability of our findings. Although cholesterol and albumin levels were similar between groups, other unmeasured factors, such as dietary habits – which we could not assess objectively – air quality, or ultraviolet radiation exposure, may have influenced the results. However, these factors could not be objectively assessed. Furthermore, due to the lack of blood gas data, we were unable to evaluate differences in blood oxygen pressure or other related parameters. While severe CAD can lead to reduced LVEF, our study focuses on the association between LVEF and SYNTAX score rather than establishing a causal relationship. Additionally, since LVEF was measured within 24 h after the procedure, it may have been affected by acute hemodynamic changes during NSTEMI. Given the cross-sectional nature of our study, causality cannot be determined, which remains a limitation. Although we used propensity score weighting methods to minimize bias, unmeasured factors such as differences in primary and secondary prevention strategies, healthcare access, and cardiology service availability between the two regions may have influenced our findings. While both study centers were major hospitals serving as referral centers in their respective regions, variations in preventive measures and healthcare utilization patterns could not be fully accounted for.

These limitations highlight the need for larger, multicenter studies conducted across a wider range of altitudes to confirm and expand upon our findings.