Introduction

Malignant glioma, accounting for 80% of brain cancer cases, is the most invasive primary brain tumor in adults, categorized as grade IV glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) by the World Health Organization (WHO), and originates from glial cells, including oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and ependymal cells [1, 2]. Despite extensive research, the etiology of glioma remains poorly understood, with its risk factors largely elusive and undefined [3]. The only established environmental factor linked to an increased risk of glioma is exposure to moderate to high doses of ionizing radiation [4]. A stratified diagnostic approach, incorporating genomic markers, grading, and histology, has been developed to provide more accurate predictions for prognosis and therapy selection in biologically and genetically similar tumors, making it more applicable to clinical practice than previous methods [5, 6].

A survival rate of less than one year has been observed in most GBM patients, with only approximately 4.7% surviving beyond five years [7]. Despite conventional GBM treatment, which includes radiation and chemotherapy following surgical resection, favorable outcomes remain hindered by poor prognosis, high invasiveness, significant chemotherapy resistance, and the challenge of penetrating the blood-brain barrier [8]. Although significant progress has been made in genomic and translational research, scientists have yet to develop preventive methods, and no screening tests are available to improve disease prognosis [9]. Scientific studies have confirmed that various human disorders are linked to different degrees of mitochondrial dysfunction. One particularly lethal cancer, for which existing treatments have ultimately proven ineffective, is GBM. A distinctive Warburg phenotype, commonly observed in numerous solid malignancies, is characteristic of GBM. This phenotype is defined by a shift to aerobic glycolysis instead of OXPHOS, regardless of oxygen availability [10].

Glucose uptake in GBM cells has been observed to be at least three times higher than in normal brain tissue, and highly glycolytic GBM has been linked to poor prognosis [11]. This underscores the inadequately understood role of mitochondrial dysfunction in malignant tumor development. Gaining insight into metabolic alterations in cancer cells could lead to novel therapeutic strategies. However, the diverse metabolic characteristics and adaptability of cancer cells to varying conditions complicate this approach. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of cancer metabolism is essential for the effective diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of GBM.

Researchers have actively investigated disturbances in mitochondrial OXPHOS, in alignment with energy metabolism, to develop targeted the-rapies for GBM treatment. Their focus has been on adapting treatments to address mitochondrial metabolic dysfunctions. Consequently, this review highlights how dysfunctional mitochondria influence GBM malignancies, as recent research has linked this impact to factors such as mtDNA deficiencies, impaired OXPHOS complexes, and imbalanced ROS production.

Mitochondrial defects in GBM

Having evolved from free-living bacteria, mitochondria have been established as intracellular organelles with an oval shape, measuring between 0.5 and 10 µm in dia-meter. Their role in eukaryotic cell formation through endosymbiosis has been recognized [12]. Mitochondria possess a dual-layer membrane that creates an intermembrane space enclosing an electron-dense matrix. The inner membrane is highly folded into the matrix, forming cristae that contain the mitochondrial respiratory machinery. The density of these structures varies depending on energy demand. The outer membrane, which is permeable via the voltage-dependent porin anion channel, allows mole-cules up to 5 kDa to diffuse and transmits signals into the mitochondria [13]. Interactions with other organelles, including lysosomes, endosomes, peroxisomes, endoplasmic reticulum, lipid droplets, and the plasma membrane, are crucial for optimizing cellular function.

According to the endosymbiotic hypothesis, primitive mitochondria were engulfed by anaerobic eukaryotic cells, leading to a mutually beneficial symbiosis. Mitochondria have been identified as essential organelles containing genetic material in the form of self-replicating circular mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which resides in the intermembrane matrix space. They can exist as individual organelles or form intricate three-dimensional networks. Their active transport to distinct subcellular sites and continuous merging and division regulate their size, shape, and quantity through fission and fusion [14].

Additionally, mitochondrial fluctuations have been observed based on the cell’s metabolic demands and type, varying throughout different cell cycle phases and continuously adapting under both normal physiological and pathological conditions. This adaptability allows mitochondria to play active roles either individually or collectively.

Mitochondria serve as the primary site for macromo-lecule oxidation, primarily amino acids, carbohydrates, and lipids, while also supplying energy for OXPHOS during ATP generation and contributing to reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and sequestration [15]. Furthermore, mito-chondria play essential roles in regulating calcium ion concentration, cellular metabolism, proliferation, gene expression, and apoptosis. Their functions as regulators of redox signaling and other cellular signaling networks have been well established, along with their contributions to protein transport, inorganic phosphate import, and the maintenance of mitochondrial membrane potential [16]. Given their pivotal role in cellular regulation, alterations in mitochondrial genes may contribute to disease development. Mitochondria also directly influence synaptic plasticity in the brain by regulating neurotransmitter production and inactivation. They actively contribute to synapse formation and maintenance while regulating neurogenesis, neuronal development, and axonal movement during synaptic plasticity [17, 18].

GBM exhibit profound structural and functional abnormalities that distinguish them from those in normal brain cells. Abnormalities in mitochondrial membrane composition and functionality have been identified in GBM, where immature cardiolipin with shorter acyl chains was found in high abundance compared to the normal cortex of brain tissues, which contains mature cardiolipin with longer acyl chains. This indicates alterations in the tumor microenvironment, highlighting proteins directly involved in mitochondrial energy production [19]. Furthermore, GBM exhibits mitochondria with significant cristolysis, with only some of the glioma cells containing healthy, electron-dense mitochondria. These mitochondria exhibit morphological changes suggesting that the mitochondrial inner membrane potential was lost, with a severe impact on the respiratory chain [20].

In a landmark study, a lower mitochondrial reserve capacity was found to be governed by aberrant cellular signaling, predominantly attributed to the repression of pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase catalytic subunit 1 and the RAS-mediated regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase activity, a common metabolic alteration observed in patient-derived GBM stem cells [21]. Mitochondrial alterations in GBM have been demonstrated through ultrastructural morphometric analysis, which revealed a significant reduction in the fluorescent signal of Mito-Tracker Red in GBM cells compared to those treated with rapamycin, along with a notably lower mitochondrial count [22]. Furthermore, in comparison to lower-grade gliomas, GBM mitochondria displayed a smaller surface area, reduced perimeter, increased cristae density, and a more rounded morphology [23]. Grespi et al. [24] reported that GBM exhibits altered expression of genes associated with the cytoskeleton and mitochondria-endoplasmic reticulum contact sites, suggesting a potential connection between these changes and the tumor’s aggressive behavior. Additionally, a machine learning-based analysis of transmission electron microscopy images revealed that GBM displays a more integrated morphology of mitochondrial respiratory cristae [23]. Another distinct ultrastructural feature of GBM is the significantly higher number of inter-}mitochondrial junctions compared to normal brain cells. This observation was supported by in situ cryo-electron tomography, which enabled nanoscale visualization of mitochondria within their native cellular environment, particularly in protrusive and peripheral regions, indicating enhanced mitochondrial communication in GBM cells [25]. Collectively, these findings highlight the critical role of mito-chondrial structural abnormalities in promoting GBM progression and invasiveness.

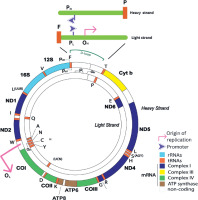

Hundreds to thousands of mtDNA copies may be present within a single cell, remaining independent of the cell cycle as mitochondrial biogenesis occurs [26]. The 16,569-base-pair nucleotide mtDNA is arranged in a double-stranded, circular structure that lacks introns and consists solely of exons. The number of mtDNA copies per cell aligns with the tissue’s energy demands, and inheritance occurs exclusively through the maternal line. Over the course of evolution, most mitochondrial genes have either been lost or transferred to nuclear DNA (nDNA), reducing mtDNA to only 37 genes, including 13 essential polypeptides required for the mitochondrial respiratory chain and OXPHOS subunits, 2 ribosomal RNA (12S and 16S rRNA), and 22 transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules [15].

Human mtDNA consists of light (inner) and heavy (outer) circular DNA strands, each with a distinct origin of replication, termed OL and OH, respectively. Gene expression is regulated by promoters on the heavy strand (PH1 and PH2) and the light strand (PL) (Figure 1). The mtDNA-to-nDNA ratio ranges from 25.6 to 3882.4 and is categorized into low and high groups based on the median mtDNA copy number. Furthermore, the D-loop serves as the primary site where nuclear-encoded factors involved in mtDNA trans-cription and replication interact with the mitochondrial genome to regulate these processes. It is the key non- coding region of mtDNA, responsible for initiating OH strand replication and promoting PL, PH1, and PH2 transcription.

Figure 1

The circular human mitochondrial DNA comprises 37 genes that are crucial for normal mitochondrial function and essential for cellular energy production

Genes encoded in both nDNA and mtDNA are assembled to form respiratory complexes. Complex I consists of 45 polypeptides, seven of which (ND1, -2, -3, -4, -4L, -5, and -6) are encoded by mtDNA. Complex II is composed entirely of four nuclear-encoded polypeptides. Complex III includes 11 polypeptides, with cytochrome b encoded by mtDNA. Complex IV consists of 13 polypeptides, of which three (COI, -II, and -III) are encoded by mtDNA. Complex V contains approximately 16 polypeptides, with ATP6 and ATP8 encoded by mtDNA. Among these complexes, only Complexes I, III, IV, and V function as proton transporters and retain mtDNA-encoded polypeptides. These four complexes, along with two electron carriers (cytochrome c and ubiquinone), form essential components of the ETC, facilitating ATP synthesis through OXPHOS [27].

Alterations in the GBM mtDNA and its related machinery

mtDNA mutations can function as contributors to tumorigenesis. Studies have reported that a higher frequency of somatic mtDNA mutations correlates with an increased likelihood of recurrent tumors in GBM, which exhibits the highest rate of somatic mutations [28]. Fur-thermore, the absence of protective histones, the pro-xi-mity to mutagenic ROS production sites, and limited DNA repair mechanisms have rendered mtDNA highly polymorphic and particularly susceptible to mutations [29]. Biologically, researchers have determined that mtDNA polymorphisms are ancient evolutionary traits and homoplasmic, meaning they are uniformly present in all mtDNA molecules. In contrast, pathogenic mtDNA mutations occur in a heteroplasmic manner, affecting only a subset of mtDNA molecules, with varying ratios across different tissues [16]. Replication errors resulting from the oxidative inactivation of PolgA’s proofreading exonuclease activity can lead to mtDNA mutations [30]. Approximately 60% of solid tumors, including colorectal [31] and ovarian carcinomas [32], acute myeloid leukemia [33], and GBM [34], have been found to harbor mtDNA mutations, which are implicated in phenotypic alterations in tumors and the dysregulations in replication and transcription processes.

There is substantial research evidence supporting the concept that alterations in mtDNA represent early modifications in the development of the tumorigenic phenotype. mtDNA mutations, particularly within regulatory regions such as the displacement loop (D-loop), have been implicated in promoting therapy resistance in various cancers. For example, the m.16126T>C mutation in the D-loop has been associated with altered mitochondrial replication and transcription, leading to disrupted mitochondrial function and OXPHOS capacity [35]. This mitochondrial dysfunction can hinder the production of ROS, which are critical mediators of DNA damage induced by chemoradiation, thereby reducing its cytotoxic effectiveness [36]. Furthermore, mtDNA mutations have been shown to activate mitochondrial retrograde signaling, which enhances nuclear gene expression promoting cell survival and DNA repair pathways, further contributing to resistance against chemotherapy and radiotherapy [37]. Clinical evidence has also linked the accumulation of mtDNA mutations to poor treatment response and shorter progression-free survival in patients undergoing chemoradiation, highlighting their role as functional contributors to therapeutic failure [38, 39]. Furthermore, the D-loop m.16126T>C variant was identified in 18% of GBM samples and was asso-ciated with a reduced median survival of only 9.5 months in patients, along with dysregulated pathways that promote tumor proliferation and invasion, as indicated by molecular marker analysis of GFAP, p53, ATRX, and Ki67 [40].

Mutations and variations in mtDNA can compromise the effectiveness of chemoradiation. Sravya et al. [41] investigated the development of temozolomide resistance and found that mtDNA-depleted GBM cell lines exhibit-ed reduced sensitivity to radiation and temozolomide treatment. This resistance was mechanistically linked to elevated expression of stemness markers and significant hypomethylation of nDNA, which allowed cancer cells to remain undifferentiated and sustain their self-renewal capacity [42]. Most recurrent GBM tumors harbor somatic mtDNA mutations linked to prior radiotherapy, which induces hypermutation in subsequent recurrences through a mechanism that typically arises under selective pressure during tumor evolution [28, 43]. Furthermore, specific nDNA mutations in the IDH1 gene at codon 132, which encodes the mitochondrial enzyme isocitrate dehydrogenase, have been shown to contribute to temozolomide resistance by affecting oncometabolite production and altering mitochondrial function [44].

Mutations in mtDNA-encoded ETC Complex I subunits have been detected in GBM, with these alterations potentially contributing to the shift toward glycolysis by impairing ETC function. Additionally, over 200 mutations have been identified in the mtDNA of GBM cells and tissues, including nine non-synonymous mutations in Complexes III and IV, which have been hypothesized to impact OXPHOS [45]. Similarly, Cai et al. [46] identified positive associations between Complexes II and IV and the level of mtDNA genes in relation to p53-dependent senescence in GBM cells. Vidone et al. [47] examined patient samples and found that 43% of tumors harbored at least one de novo mutation in GBM. This observation has been supported by another study that detected a high number of mutations, although these did not meet the prioritization criteria for tumorigenesis factors [48]. Up to 75% of all glioma samples, including GBM, have exhibited at least one somatic mtDNA mutation. However, no significant correlation has been established between these mitochondrial mutations and the various grades of glioma [28]. Similarly, a study found no consistent associations linking inherited mtDNA sequence variants with glioma risk in two case-control study populations from the US and the UK [49].

Kozakiewicz et al. [50] identified 21 missense and 46 various sense-change polymorphisms in mtDNA Complex I among brain tumor patients of different grades. The most frequent polymorphism, T4216C, was detected in 13.3% of patients and was particularly common among those with GBM. In silico analysis has classified Complex I polymorphisms and mutations as deleterious, indicating their association with carcinogenesis by altering the biochemical properties of proteins. Additionally, a base pair substitution from T to C in the ND6 subunit of Complex I has been observed, leading to enzyme stabilization and increased resistance to hypoxic conditions and rotenone [51]. Somatic mutations in patients with GBM have been pri-marily detected in the ND3 region, the D-loop, and the Complex V locus, specifically the COX3 gene [28]. Li et al. [52] found a significant association between the m1555 A>G of mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene variant and increased childhood GBM risk, particularly in European and Hispanic populations.

Another key indicator of mitochondrial presence is mtDNA copy number, which reflects the mitochondrial count within a cell. Variations in mtDNA copy number play a crucial role in the activation and progression of tumorigenesis [53]. A multiomics cluster analysis was conducted to explore the associations between gene copy number variations (CNV-Gs) and methylation gene changes (MET-Gs) in GBM. The analysis revealed a notable variation in the distribution of CNV-Gs on chromosomes 1 and 2, along with a similarly pronounced difference in DNA me-thylation frequency both in vivo and at the transcription initiation site [54].

Elevated DNA methylation at exon 2 of POLGA has been associated with a reduced mtDNA copy number. This reduction has been observed to drive HSR-GBM1 cells to rely on glycolysis for ATP production rather than OXPHOS, thereby promoting cell proliferation [55]. A decreased mtDNA copy number has been linked to lower overall survival in adult GBM patients [56], with an even worse prognosis among younger GBM patients [57]. In pediatric high-grade gliomas, mtDNA copy number is significantly reduced, leading to a glycolytic phenotype that is strongly associated with enhanced cell migration and invasion, cancer resistance, and in vivo tumorigenicity [58].

In addition, some epigenetic studies have investigated how DNA modifications influence mRNA expression in GBM without altering the genetic sequence. One such alteration is GBM mtDNA methylation, which decreases during the early stages of tumorigenesis but increases in the later stages, particularly in GBM [59]. These findings provide evidence that mtDNA plays a role in tumor deve-lopment and suggest that changes in mtDNA, primarily increases, are an early feature of the process leading to malignant behavior. Another key aspect of GBM progression is the regulation of mtDNA by long non-coding RNAs in GBM tissue and cell line samples. These mRNA-like transcripts range from 200 nucleotides to 100 kb in length, with minimal protein-coding potential. LncRNA RMRP transcripts were elevated in GBM tissues and aberrantly expressed compared to normal brain tissue. This was significantly associated with advanced tumor grade and linked to a relatively poor prognosis [60].

Alterations in nucleoid packaging of GBM mtDNA have also been observed. These involve components of mtDNA that are closely associated with the inner mitochondrial membrane, interacting with the protein components of the nucleoid, and are believed to contribute to tumori-genesis. One of the most abundant structures in this system is mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM). Franco et al. [61] targeted TFAM, which exhibited higher expression in U87 GBM, using melatonin. TFAM can interact with mtDNA in a non-specific manner to facilitate the packaging and preservation of genetic material. A TFAM-mtDNA association was observed when melatonin-induced TFAM downregulation also reduced mtDNA transcription. A recent study found that higher TFAM expression in glio-ma tissues was positively correlated with tumor grade, as determined through immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry. In recurrent GBM specimens, TFAM expression was higher compared to primary GBM. A simi-lar TFAM-mtDNA association was observed when TFAM depletion through the diterpenoid honatisine induced mito-nuclear protein imbalance by suppressing mtDNA replication and transcription [62]. Table 1 summarizes several mtDNA mutations in GBM that cause significant functional alterations and have clinical relevance.

Table 1

Summary of mitochondrial DNA mutations in glioblastoma multiforme and associated clinical impacts

| GBM mtDNA mutations | Clinical correlation and functional impacts | References |

|---|---|---|

| Gene loci of ND3, D-loop region, and Complex IV subunit COX3 | Increased frequency of somatic mtDNA mutations correlates with tumor recurrence in GBM. | [28] |

| D-loop m.16126T>C variant | Dysregulation of mitochondrial replication or transcription is associated with a reduced median survival of only 9.5 months in patients. | [35, 46] |

| T4216C polymorphism in the mitochondrial gene MT-ND1 of Complex I | This variant was identified in 13.3% of patients, resulting in an amino acid substitution with a significant impact on the biochemical properties of the metabolic protein. | [45] |

| Insertion of a cytosine (C) residue at position m.10946 in the ND4 gene of Complex I | It induced a marked reduction in Complex I protein function and structure. | [42] |

| Variants in the ND6 gene of Complex I at positions 14159 bp and 14160 bp | Partial dysfunction of the ETC limits cellular metabolism to anaerobic glycolysis and activates rapid cell proliferation. | [46] |

| A variant A>G at position m.1555 in the 12S rRNA gene | This variant is significantly associated with childhood GBM risk, exhibiting an adjusted odds ratio of 29.30, highlighting its potential as a risk factor | [47] |

Building on the previously discussed alterations in mtDNA, accumulating evidence indicates that dysregulation of mtDNA repair mechanisms also plays a critical role in GBM pathogenesis and resistance to therapy. Mitochondria possess multiple DNA repair pathways, including base excision repair (BER), direct damage reversal, mismatch repair, and recombinational repair [63]. GBM cells exhibit resistance to temozolomide by engaging the BER pathway to repair cytotoxic lesions such as 3-methyl-adenine (3-meA) and abasic sites. Suppressing key components of the BER pathway, namely alkyladenine-DNA glycosylase (AAG) and apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 (Ape1), has been shown to sensitize GBM cells to treatment [64]. Additionally, the regulation of DNA repair pathways by poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs) is critical in determining therapeutic outcomes in GBM. Notably, stearoyl-CoA desaturase has been found to influence PARP1 activity, thereby modulating DNA repair capacity; its downregulation leads to increased DNA damage accumulation and impaired repair efficiency [65]. Furthermore, mismatch repair activity is essential in GBM cells, where it activates the E3 ubiquitin ligase RAD18, facilitating post-replicative gap filling and promoting cell survival in response to temozolomide-induced DNA damage [66]. Collectively, these findings highlight the significance of targeting dysregulated DNA repair mechanisms, both mitochondrial and nuclear, to enhance the therapeutic efficacy in GBM.

Therefore, it is imperative to conduct further research to determine the extent to which mitochondrial genome mutations contribute to the growth and progression of GBM, rather than merely acting as molecular indicators of mitochondrial dysfunction. This highlights the need to elucidate the roles of identified mtDNA mutations in GBM and to assess the capacity of these mitochondrial genome mutations to modulate cancer growth and progression, rather than simply serving as markers of mitochondrial dysfunction.

Energy production and metabolism in brain mitochondria: insights into GBM

Mitochondria are the cell’s powerhouses, responsible for generating ATP through the metabolism of macromolecules such as amino acids, fatty acids, and glucose. Proper brain function heavily relies on the energy transformation facilitated by mitochondrial OXPHOS. In neurons, glucose serves as the primary energy source, undergoing catabolism to generate pyruvate, which is then transported to the mitochondria for further processing through OXPHOS and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. Upon entering the mitochondria, pyruvate is converted into acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) by the enzyme pyruvate dehydrogenase. Subsequently, acetyl-CoA enters the TCA cycle, where it undergoes oxidation, producing NADH and FADH2. These molecules, which carry high-energy electrons and protons, feed into the ETC, generating a significant electrochemical gradient essential for ATP production, thereby emphasizing the crucial role of mitochondria in sustaining brain energy metabolism. Hence, the four proton-pumping complexes must have coevolved with their electrical components [18]. Indeed, brain cells constantly depend on high-energy metabolism, with a precise linkage between energy demand and supply demonstrated through the delivery of glucose and oxygen from the vasculature. Researchers have found that disruptions in homeostasis and metabolic processes can lead to various brain tumors and neurodegenerative diseases [49, 67, 68].

Cancer cell metabolic reprogramming is influenced by genes and factors in the tumor microenvironment. Although significant progress has been made in understanding the metabolic adjustments that enable GBM cells to meet their nutritional needs, the specific metabolic changes required for GBM invasion, a characteristic feature of this cancer, remain incompletely understood.

Otto Warburg’s [69] initial discovery revealed that tumor cells have relied less on OXPHOS for ATP production in mitochondria and have predominantly depended on glycolysis in the cytosol, even in well-oxygenated environments, including GBM. Researchers have proposed that mitochondrial damage and aerobic glycolysis drive tumori-genesis, and they are currently exploring the mechanisms by which cancer cells require higher energy levels than normal cells.

The elevated aerobic glycolysis rates in tumor cells are now regarded as essential not for directly generating ATP or compensating for defective mitochondrial function but for supplying materials necessary for anabolic metabolism. Evidence suggests that in proliferating cancers, mitochondria have been reprogrammed to ensure that the high energy demands for cell division, migration, and invasion are met [70]. An emerging characteristic of GBM has been identified as deregulated cellular energetics. GBM cells actively promote aberrant energy generation through aerobic glycolysis and exhibit natural apoptotic resistance [71].

The apparent contradiction between aerobic glycolysis and mitochondrial dysfunction in GBM can be reconciled by recognizing that these two phenomena represent distinct but complementary aspects of metabolic reprogramming. While the Warburg effect highlights GBM cells’ pre-ference for glycolysis over OXPHOS even in the presence of oxygen, this shift does not imply complete mitochondrial inactivity. Instead, mitochondrial dysfunction in GBM often refers to reduced efficiency in mitochondrial respiration, while the organelle retains essential functions in biosynthetic pathways, redox balance, and cell survival mecha-nisms. Recent studies underscore the complexity of this metabolic reprogramming. For instance, Wang et al. [72] demonstrated that glucose starvation prompts resistant GBM cells to enter a quiescent state, thereby enhancing their resistance to temozolomide. This finding challenges the notion that combining chemotherapy with glucose deprivation universally induces tumor cell death. These results support the idea that GBM cells rely on glycolysis not solely for energy production, but also to mitigate me-tabolic stress during therapeutic interventions. To support anabolic metabolism, the preferential use of glycolysis in GBM is mechanistically linked to elevated ratios of pyruvate kinase isoenzymes M2 to M1 (PKM2/PKM1), primarily driven by PKM2/PKM1-dependent transcriptional activity of NF-κB/RelA genes [73]. Additionally, elevated ROS levels under hypoxic conditions promote GBM progression by activating the HIF-1α pathway and upregulating SERPINE1 expression [69]. This aligns with the Warburg effect, as hypoxia-inducible signaling enhances glycolytic flux, and the regulation of bioenergetics plays a critical role in tumor progression [74]. Although mitochondrial respiration may be compromised, mitochondria are repurposed to support anabolic processes and buffer ROS rather than serve as the primary source of ATP.

Song et al. [75] found that pyruvate kinase isoform 2 (PKM2) was significantly overexpressed in glioma sphe-roids and modulated cell differentiation and death. It acts as a regulator of GBM cell metabolism, leading to the accumulation of glycolysis intermediates, which sustain tumor growth by providing substrates for nucleic acid, amino acid, and lipid precursors. A group of GBM cells derived from patients with higher stemness markers exhibited elevated glycolytic function compared to GBM cells with lower stemness markers. In this group, mRNA transcript levels of glycolytic enzymes (GAPDH, PFKP, LDHB, and LDHA) were significantly elevated. This suggests that high expression of glycolytic enzymes may correlate with greater stemness in GBM [76]. The aldolase family plays a key role in glycolysis. In high-grade GBM, brain-specific fructose- bisphosphate aldolase C (ALDOC) was significantly downregulated. Further analysis revealed a potential regulatory mechanism between ALDOC and IDH1, where ALDOC mRNA and protein expression showed an inverse correlation with non-mutated IDH1 expression in GBM patient cohorts [77]. GBM exhibits higher RNA alternative splicing compared to lower-grade gliomas. A study showed that RNA alternative splicing can be regulated by mutant EGFR or IDH1 through functional mechanisms related to the genes CERS5 and MPZL1, promoting GBM malignancy [75].

Mitochondrial homeostasis is tightly regulated by mito-chondrial reprogramming and axonal transport mechanisms. Increasing attention has been directed toward mito-chondrial dynamics, particularly their movement within and between cells. In GBM, metabolic heterogeneity facilitates interactions with the microenvironment through mitochondrial exchange, underscoring a complex relationship that promotes tumor progression and resistance to therapy. This process, known as horizontal mitochondrial transfer, enhances tumorigenicity by enabling the acquisition of functional mitochondria rather than resulting from mitochondrial defects. Astrocytes donate mitochondria to GBM cells through actin-based intercellular connections, a process mediated by growth-associated protein 43, leading to a marked increase in both basal and maximal respiration rates. This mitochondrial acquisition is further linked to a sustained rise in tumorigenic potential by promoting progression through the proliferative G2/M phase of the cell cycle, indicating a functional role in supporting tumor cell proliferation and metabolic activity [78].

OXPHOS complex impairment

Feichtinger et al. [79] compared the enzymatic activities of OXPHOS complexes between GBM and lower grade astrocytomas. Complexes I, II, III, and IV were significantly reduced by 56% to 92% in GBM. Further specific alterations were observed using immunohistochemical staining, with GBM exhibiting severe deficiencies in Complexes IV and II.

Alterations in the mitochondrial proteome demonstrated a decrease in the levels of proteins involved in GBM energy metabolism, including 23 component proteins of Complex I. Protein–protein interaction analysis showed a reduction in multiple proteins associated with energy metabolism, primarily in Complex I [80]. In GBM, mitochondrial Complex III has bypassed Complex I to drive ROS production and activate guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G protein)-coupled receptor 17 (GPR17) signaling [81]. Researchers observed that in GBM, Complex I activity was significantly reduced, and gene expression was markedly altered. TG02, a pyrimidine-based multikinase inhibitor, suppressed Complex I activity by influencing the transcriptional regulation of glycolytic processes. TG02 induced a reduction in CDK9 activity without significantly decreasing CDK9 protein expression. However, it is unlikely that TG02’s suppression is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, as upregulation of glycolysis should compensate for the reduced energy production [82]. U87 GBM cell lines exhibited resistance to tozasertib, characterized by the upregulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoenzyme 4, suppression of pyruvate dehydrogenase activity, increased mitochondrial mass, and heightened activation of mitochondrial metabolic pathways [83].

Research has highlighted that radioresistant glioma cells exhibit higher levels of NADH–ubiquinone oxidoreductase Complex I subunits and increased mitochondrial copy numbers [84]. GBM immune escape has been found to result from elevated expression of the OMA1 gene, which encodes a metalloprotease residing within the inner mitochondrial membrane. OMA1 can competitively bind to HSPA9 to initiate mitophagy and regulate GBM immune escape [85]. Metabolism and cancer signaling systems are closely linked to the mitochondrial gatekeeper, voltage-dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC1), which regulates the transport of meta-bolites and ions across mitochondria. VDAC1 has been found to be highly expressed in the outer mitochondrial membrane of GBM through signaling pathways involving NDUFS8, a subunit of the Complex I respiratory chain [86]. High Complex I activity has been observed in GBM C6 cell lines, supporting the notion that transformed cells, through juglone-competitive inhibition of Complex I, tend to increase their reliance on OXPHOS.

The concomitant administration of gamitrinib, an inhi-bitor of mitochondrial chaperones, and panobinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, reduces energy metabolism. This mechanism involves the suppression of Complex II protein expression, leading to a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential. Consequently, cytochrome C generation is activated, which then triggers caspase 9 activation, followed by the activation of both caspase 3 and caspase 7 [87].

Lloyd et al. [88] conducted a study aimed at identifying and functionally predicting a spectrum of mutations primarily in mitochondrial Complexes III and IV of GBM. They used next-generation sequencing to obtain complete mitochondrial genomes from 10 GBM cell lines and compared this dataset with mitochondrial genomes from GBM tissues of 32 patients. The research identified 25 nonsynonymous mutations in Complexes III and IV, 9 of which were predicted to be functional and likely to influence mitochondrial respiratory chain activity.

The remodeling of the OXPHOS complexes resulted in a notable reduction in the activities of Complexes I and V, while Complexes II, III, and IV exhibited increased acti- vity [89]. Notably, a reduction in the activity of Complexes II, III, and IV enhances the susceptibility of GBM cells to temozolomide-induced apoptosis [90]. Soon et al. [91] investigated mtDNA sequence variations in various grades of glioma cell lines compared to normal astrocytes. The 1321N1 and SW1783 cells harbored a substantial number of coding region sequence variations, leading to amino acid transformations in the encoded proteins. In contrast, the GBM LN18 cell line harbored five regions of sequence changes, none of which resulted in amino acid alterations, thereby maintaining normal mitochondrial function. Further investigation revealed that at least one mtDNA gene somatic mutation was present in 75% of gliomas, with 45% of these mutations classified as pathogenic. GBM samples exhibited the highest average number of somatic mutations, with 3.47 nucleotide changes per sample [28].

Radioresistance of GBM cell lines and patient-derived xenolines was associated with an increase in Complex IV activity due to a switch in the expression from subunit 2 to subunit 1. It was deduced that Complex IV isomer 1 promotes the assembly of supercomplexes and induces ROS production, leading to GBM resistance [90]. The organization and function of these supercomplexes rely on the protein Complex IV subunit 7A2L, which plays a role in assembling the supercomplex from Complex III to Complex IV. It facilitates supercomplex formation by assembling Complex III, thereby sustaining each complex and reducing ROS generation [92]. Its expression increased fourfold after 48 hours of nutritional deprivation in U87 GBM cells, where galactose replaced glucose, inducing mitochondrial energy metabolism. Furthermore, its expression in GBM was upregulated following oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide. However, the organization of the mito-chondrial transport chain and the generation of super-complexes in U87 GBM cells remained intact [93].

In Complex V, the mRNA expression of ATP5B and ATP5A1 was elevated, which was associated with the microvascular proliferation of GBM endothelial cells. This overexpression resulted from the downregulation of target gene-miRNAs and was not linked to any genomic alte-rations [94]. As for ATP6 mRNA, a subunit of Complex V, its gene expression was reduced. This subunit encodes the α component responsible for facilitating proton movement in GBM [95]. GBM cells enhance intracellular lipid, amino acid, and nucleotide stores by increasing extracellular uptake, promoting de novo synthesis, and utilizing various biochemical pathways such as glycolysis to supply carbon for nucleic acid synthesis.

Imbalanced production of ROS in GBM

Mitochondrial ROS are byproducts of OXPHOS, arising from the leakage of electrons along the ETC during regu-lar respiration. They constitute a family of free radicals formed by the partial reduction of intracellular oxygen species, including superoxide anions (O2–), hydroxyl radi-cals (OH–), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [96]. The electrons derived from NADH or FADH2 are transferred to O2, resulting in the generation of superoxide, which is then transformed into H2O2 through dismutation [97]. Typically, these two species are maintained at low levels within cells and are tightly regulated to sustain signal transduction and prevent cellular damage. However, when their concentrations exceed normal physiological levels, their ability to transmit specific signals is lost, leading to an imbalance between antioxidant activity and ROS generation, a condition known as oxidative stress. Cellular stress arises from aberrant metabolism, impaired cell cycle progression, and DNA damage induction [98]. GBM cells exhibit higher expression and activity of superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase as a defense mechanism against oxidative stress [99, 100]. Thus, cellular redox abnormalities are intricately linked to tumorigenesis and influence cellular fate decisions, including those observed in GBM [101].

It has been postulated that excessive mitochondrial ROS, once it reaches the nucleus, can induce DNA modi-fications that alter gene expression patterns. Notably, their extreme accumulation drives cancer cell cytotoxicity and cell death. It has also been suggested that ROS act as crucial second messengers mediating several intracellular pathways. They can cause oxidative modifications in a variety of proteins, including receptors, kinases, phosphatases, caspases, and transcription factors, through various cell signaling pathways [102]. ROS produced by nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (NOX) can promote GBM growth in gliomasphere cultures under hypoxic conditions in the presence of phosphate and tensin homolog (PTEN) [103]. These ROS oxidize and inactivate PTEN, leading to activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, which enhances cell proliferation and survival. This interaction between NOX-derived ROS and PTEN inactivation under hypoxia provides a mechanistic explanation for GBM progression and is consistent with the broader understanding of PTEN’s regulatory role in cancer biology [104, 105]. Furthermore, NOX activation induces the invasion and migration of U87 GBM cells, which is fostered by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate. Higher ROS accumulation subsequently activates the MAPK and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)/prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) pathways, thereby increasing the in vitro migration and invasion rate of U87 GBM cells [106].

High levels of oxidative stress have been observed in GBM, inducing a significant immune interaction mecha-nism involving modulation of macrophage levels in the GBM microenvironment [107]. Furthermore, the oxidative stress enzyme manganese superoxide dismutase exhi-bited higher relative protein expression across more than 200 astrocytic tumors. This increase correlated with tumor grade, with GBM showing a significant rise in expression [108]. A distinctive ROS modulator, Romo1, was found to be ele-vated in several GBM cell lines compared to normal astrocytes. After knockdown in three GBM cell lines, Romo1 levels significantly decreased, and a similar reduction in ROS production was observed [109]. ROS accumulation is induced by hypoxic stimuli, leading to its upregulation in three GBM cell lines: U251, U87, and LN299. The highest ROS levels were observed 12 hours after hypoxic exposure, resulting in an increased cell proliferation rate without any significant impact on GBM cell apoptosis [110]. GBM cells are particularly susceptible to elevated ROS production, which influences tumor progression and the cell cycle, ultimately contributing to drug resistance in GBM. However, these cells can also overcome oxidative stress by enhancing their antioxidant systems and increasing P-gp pump efflux to maintain redox balance [111].

Research has successfully validated the role of neuro-kinin-1 receptor (NK1R) activation by substance P in inducing oxidative stress through a remarkable elevation in ROS production in U87 GBM cells. This activation can contri-bute to GBM pathogenesis by increasing GBM meta-bolic activity [112]. The synthesis of ROS by mitochondria can be influenced by the activity of potassium channels, which modulate the entry of calcium ions into the mitochondrial matrix. It has been demonstrated that inhibiting the BKCa channel in U87 GBM cells causes a significant increase in ROS, leading to apoptosis [113]. Kv1.3, a potassium channel of the shaker family, exhibits elevated expression in both the plasma membrane and inner mitochondrial membrane of GBM LN308 cells, playing a crucial role in triggering apoptosis [114]. Furthermore, the median level of total antioxidant capacity in GBM patient tissue was significantly reduced compared to normal brain tissue. This finding is supported by significantly higher levels of oxidative DNA damage products, as measured through immunohistochemistry, enzyme immunoassay, and whole-body oxidative stress load assessment via urinary excretion of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine in GBM patients with both IDH1-mutant and IDH1-wildtype tumors [115]. The antioxidant capacity of GBM cells decreases as tumor aggression increases. Hence, balancing ROS levels represents a pro-mising approach for therapeutic intervention.

To study GBM cell invasiveness, researchers employed a multiomics approach that combined a CRISPR screen of metabolic genes with 3D invasion devices and patient biopsies. It was discovered that nicotinamide is significantly upregulated in GBM cells. It serves as a precursor for nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), which normally inhibits ROS generation [116]. Dysregulation of the PTEN/PI3K/Akt signaling axis has been widely implicated in the pathogenesis of various cancers, including multiple myeloma and glioblastoma. As reviewed by Alimohammadi et al. [117], loss of PTEN function leads to increased cell proliferation, enhanced survival, and the-rapeutic resistance in multiple myeloma. Consistently in GBM, aquaporin 8, regulated by the ROS/PTEN/AKT pathway, can lead to elevated ROS levels, resulting in reduced expression of PTEN and increased expression of phospho-rylated AKT (p-AKT). This, in turn, promotes the growth and proliferation of GBM U-251 cells in vitro [118]. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) can drive GBM progression through ROS production. The pro-neoplastic and pro-invasive activity of EGF has been linked to ROS, promoting the invasiveness of GBM T98G cell lines via an EGFR/ROS-dependent pathway [119].

Targeting mitochondria OXPHOS metabolism as a GBM therapeutic strategy

Recent GBM profiling has revealed metabolic altera-tions, which will be examined. Here, we outline the critical role of metabolism in GBM growth and describe recent clinical treatments targeting GBM metabolism to improve the quality of life. Since mitochondrial metabolic activity is essential for cancer cell proliferation, inhibiting this pathway may effectively hinder disease progression. Numerous proteins essential for mitochondrial metabolism and energy conversion are located in the dual mitochondrial membranes. These metabolic factors negatively impact cancer cell function, ultimately leading to cellular pathology. Several drugs and compounds targeting mitochondrial respiration and related processes have been developed and repurposed to specifically target mitochondria and directly influence GBM metabolism, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

Drugs targeting glioblastoma multiforme mitochondrial metabolism at different trial phases

| Mechanism of action | Molecule/Drug | Trial stage | Challenges | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting Complex I to inhibit ATP production and disrupt downstream cAMP-protein kinase A signaling | Metformin | Clinical stage, Phase II | Challenge of setting an optimal dose to ensure effective clinical outcomes. | [7, 115, 116] |

| Activation of AMPK through inhibition of Complex I in the mitochondrial ETC | Phenformin | Animal and cellular models of GBM | Safety profile concern associated with lactic acidosis. | [117, 118] |

| An inhibitor of complex I in the ETC; can suppress cell proliferation | IACS-010759 | Animal and cellular models of GBM | Incomplete inhibitory capacity. | [119- 121] |

| Inhibits Complex I activity, reduces mitochondrial membrane potential, and delays intracranial tumor growth in mice | Mito-LND | Animal and cellular models of GBM | Therapeutic uncertainty in human clinical trials. | [122] |

| Inhibits Complexes I and III, and reduces matrix metalloprotein levels and ATP levels | Verteporfin | Cellular model | Concentration sensitivity in other types of GBM cells is not fully understood. | [123] |

| Mediated by an iron chelator that induces mitochondrial stress, inhibits respiration, and disrupts the bioenergetics of Complex II | VLX600 | Clinical stage Phase I | Iron-chelation-dependent effects can reduce efficacy in environments with varying iron levels. | [124] |

| Blocks Complex III of the ETC and induces apoptosis in cancer cells | Resveratrol | Adjuvant in pre-clinical treatment | Low bioavailability limiting therapeutic effectiveness. | [125] |

| Blocks the initiation of fatty acid β-oxidation | Etomoxir | Animal model of GBM | Safety profile concern associated with liver damage. | [126, 127] |

| Targets Complex IV and induces apoptosis by producing free radicals and activating the ceramide pathway through the retinoid receptor | Fenretinide | Clinical stage Phase II and cellular model | Toxicity concern inducing fatigue, dryness of skin, anemia, and hypoalbuminemia. | [128, 129] |

| Alters the redox cycle by targeting Complex IV | Doxorubicin | Animal model | Delivery challenge due to the blood-brain barrier. | [130, 131] |

| Inhibits ATP synthase by binding to the F0 region | Oligomycin | Cellular model | Inconsistency in inhibition between treatment and basal oxygen consumption rate. | [132, 133] |

| Targets F0F1-ATP synthase and depends on the mitochondrial proton gradient | Gboxin | Animal and cellular model of GBM | Resistance mechanism involving mitochondrial permeability transition pore causing Gboxin accumulation. | [134] |

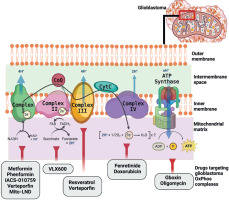

Figure 2 illustrates the ETC complexes and promising molecules that target each complex to specifically alter GBM mitochondria metabolism and induce energy impairment. Drug repurposing or repositioning is a well- established approach to expanding the availability of effective anti-GBM treatment options. Most current cancer drugs primarily focus on mechanisms associated with apoptosis, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction, aiming to minimize harmful cytotoxicity.

Biguanides, an oral antidiabetic drug class, inhibit cancer proliferation and metastasis, including GBM. Metformin and phenformin, two types of biguanides, can target Complex I in GBM by modulating the AMPK pathway [140], which plays a central role in maintaining energy balance and cellular homeostasis [141]. Metformin suppresses Complex I activity, significantly reducing U87 and U251 cell proliferation and altering mitochondrial membrane potential following treatment [142]. Meanwhile, phenformin has been shown to inhibit glioma stem cell self-renewal and decrease the expression of stemness and mesenchymal markers.

IACS-010759 inhibits the tosyl reagent AL1 from modi-fying Asp160 in the 49-kDa subunit within the quinone- access channel. Unlike other treatments, IACS-010759 inhibits both forward and reverse electron transfer in a direction-dependent manner without affecting the binding of the quinazoline-type inhibitor [126]. Verteporfin, which targets both Complex I and III, has been found effective in inducing cytotoxic effects specifically on glioma stem cells without affecting normal cells. Mito-LND acts as a potent inhibitor of GBM growth both in vitro and in vivo by decreasing mitochondrial membrane potential, thereby disrupting ROS generation balance [127]. A recent clinical trial evaluated devimistat (CPI-613), a novel therapeutic agent specifically engineered to target and disrupt mitochondrial metabolism. By impairing mitochondrial function, devimistat is intended to enhance the effectiveness of conventional chemotherapeutic agents, such as gemcitabine and cisplatin. Its therapeutic potential has been demonstrated in preclinical in vitro studies and in a Phase Ib clinical trial involving patients with advanced biliary tract cancer [143]. Notably, devimistat has shown good tolerability and an acceptable safety profile, further supporting its potential for clinical application in GBM management.

Targeting Complex II, VLX600, a novel iron chelator, induces a type of cell death that is caspase-independent through an autophagy-dependent mechanism in GBM. Moreover, extracellular iron supplementation significantly mitigates VLX600-induced cell death and mitophagy, highlighting the critical role of iron metabolism in GBM cell homeostasis.

Targeting Complex III, resveratrol has been reported to elevate ROS levels in GBM cells, disrupt cellular antioxi-dant activities, and markedly increase both intracellular ROS and lipid peroxides. Furthermore, it can inhibit oxidation–reduction processes.

Drugs targeting Complex IV, such as fenretinide (4-hydro-xyphenyl-retinamide), a synthetic retinoid, act as chemopreventive agents. Classified under retinoids, fenretinide triggers apoptosis in vitro by generating free radicals and inducing the ceramide pathway through both retinoid receptor-independent and -dependent mechanisms. Doxorubicin, which targets Complex IV in GBM, is an effective anthracycline chemotherapy agent with a univalent redox potential, potentially enhancing mitochondrial ROS production.

Oligomycin inhibits proton translocation in mtATPase Complex V, which utilizes the energy stored in the proton gradient to synthesize ATP. Salinomycin has the ability to stimulate p53, open the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, and promote mitochondrial ROS generation and accumulation. These processes ultimately lead to necrosis in U87 and U251 GBM cell lines [144].

Gboxin has been demonstrated to effectively inhibit the growth of primary mouse and human GBM cell lines while sparing normal cells, underscoring its potential as a therapeutic agent against GBM [139].

The primary therapeutic challenge in GBM treatment stems from the anatomical barrier posed by the blood–brain barrier and the highly infiltrative behavior of GBM cells, both of which hinder effective drug delivery to the tumor site [145]. Moreover, GBM cells can activate compensatory pathways to evade treatment, highlighting the need for combination therapies that simultaneously target multiple, divergent metabolic pathways [146]. A signi-ficant limitation in current clinical practice is the absence of specific biomarkers to identify patients who are likely to respond to metabolism-targeting therapies or to monitor their treatment response, especially given the substantial variability in metabolite levels across different disease states [147]. The development of such biomarkers is essential for personalizing treatment strategies and improving clinical outcomes. However, current metabolic profiling techniques face challenges, particularly in accurately capturing real-time metabolic fluxes in vivo. Additionally, discrepancies in metabolic phenotypes observed across clinical, in vitro, and in vivo models further complicate efforts to exploit GBM’s metabolic vulnerabilities [148]. Another important factor to consider is mitochondrial heterogeneity across GBM subtypes, which significantly influences metabolic plasticity, particularly in therapeutic response and adaptation to the tumor microenvironment. Distinct GBM subtypes, such as mesenchymal and proneural brain-tumor-initiating cells, exhibit unique mitochondrial activities that affect energy production and overall metabolic behavior [149]. Mesenchymal subtypes are more glycolytic, relying heavily on glucose fermentation for energy and demonstrating greater survival under hypoxic conditions commonly present within tumors. In contrast, proneural subtypes depend more on OXPHOS under normoxic conditions, generating energy more efficiently. Notably, treatment with metformin to inhibit OXPHOS elicited a stronger therapeutic response in proneural cells compared to mesenchymal cells [150]. These findings suggest that targeting mitochondrial function may be an effective therapeutic strategy, but such an approach must account for the metabolic flexibility of individual GBM subtypes. Collectively, these factors highlight the intricate nature of targeting GBM metabolism and emphasize the need for advanced profiling tools and personalized treatment approaches. Despite these challenges, targeting metabolic pathways remains a promising strategy, particularly when integrated with conventional therapies such as radiothe-rapy to improve therapeutic efficacy.

Conclusions

This review highlights the key factors contributing to the cellular and metabolic pathways in GBM, identifying emerging trends and potential treatment strategies that emphasize cellular metabolism, with a particular focus on mitochondria as the primary energy source. Alterations in these pathways are intricately associated with current GBM treatment approaches. To optimize treatment regimens, future research and clinical translation of novel therapies will require a comprehensive understanding of GBM’s molecular characteristics. A deeper insight into these mechanisms will accelerate the development of more effective therapeutic interventions for GBM treatment. These therapeutic strategies will not only target tumor cells but also exert dual-targeting effects on metabolic pathways, particularly OXPHOS. Although significant advancements have been made in medical technology, efforts to develop effective pharmacological treatments for GBM have largely been unsuccessful in clinical applications. The major obstacles in developing new therapies for GBM include diminished drug efficacy and the limited ability of therapeutic agents to cross the blood-brain barrier, as evidenced in both preclinical animal models and clinical trials. Moreover, the extensive safety and efficacy data required for new therapeutic agents often lead to prolonged development timelines, posing a substantial challenge to the rapid translation of innovative treatments from the laboratory to clinical practice.