Introduction

Endometriosis is a common gynaecological disease, which affects 10–15% of women in reproductive age. It is defined as the presence of functional endometrial foci outside the uterine cavity. Patients can experience a variety of nonspecific symptoms, but the most common are pain and infertility. Apart from this, endometriosis may present with haematuria, fatigue, painful rectal bleeding and metabolic and psychiatric disorders such as hypoglycaemia, depression, or anxiety [1–3]. Female infertility can be caused by different mechanisms such as fallopian tube destruction, chronic pelvic inflammation, changes in the immune system functions, and altered hormonal balance. Furthermore, inflammatory cytokines and cells affect eutopic endometrium, causing an implantation failure [1, 4]. Endometriosis is divided into three types: ovarian endometriosis, superficial (peritoneal) endometriosis, and deep endometriosis (DE) [1]. Deep endometriosis is defined as endometriosis invading pelvic organs more than 5 mm beneath their surface. One of the rare forms of endometriosis is urinary tract endometriosis (UTE), which can either occur as deep or superficial endometriosis. Urinary tract endometriosis affects 0.3–12% of women with endometriosis and this condition refers to/occurs in 20–52.6% of patients with DE [3, 5]. The most common location of UTE is the bladder, while the most dangerous type of UTE is ureteral endometriosis, because it can lead to silent and irreversible kidney damage. Bladder endometriosis (BE) is defined as the presence of endometrial foci in the vesical detrusor muscle (Figure 1). Bladder endometriosis most commonly affects the base and dome of the bladder [3]. The vesicouterine pouch or anterior cul-de-sac is also a common site of endometriotic involvement. Either peritoneal or deep endometriotic implants involving the serosal surface of the uterus often determine adhesions between the peritoneal folds of the bladder dome and the uterus with anteflexion of the uterus and obliteration of the anterior cul-de-sac. Bladder endometriosis was described for the first time in 1921 by Judd [6]. Since then, numerous case reports and research studies have been published regarding this topic. Despite the wide literature, the pathogenesis of BE is still unclear. Most popular theories explaining the pathogenesis of BE are retrograde menstruation, coelomic metaplasia, and the spread of stem/progenitor cells [3, 7]. At the moment, retrograde menstruation theory is considered to be the most explanatory. This theory states that menstruation blood with functional endometrial cells flows to the pelvic cavity through the fallopian tube orifices [1, 8]. Endometrial cells adhere to the peritoneum and start the inflammation facilitating the vesicouterine pouch endometriosis (EVUP) development and bladder infiltration. Novellas et al. have found that the endometrial cells implant to the outer layers of the bladder and later infiltrate the inner layers [9]. On the other hand, the retrograde menstruation hypothesis cannot explain the isolated BE form, in which case other theories seem to be more suitable. In addition, BE may be of iatrogenic origin, such as a consequence of bladder destruction during caesarean section (CS) [3, 7]. Bladder endometriosis presents a range of nonspecific symptoms such as urinary bladder pain, cyclic or noncyclic pelvic pain, dysuria, dyspareunia, increased urinary frequency, urinary incontinence, haematuria, and elevated intravesical pressure. Thus, the differential diagnosis of BE is challenging considering various mimicking diseases such as urinary tract infections, interstitial cystitis, bladder stones, and carcinoma [3, 7, 10]. As a chronic inflammatory disease, endometriosis can also have an impact on mental health, sleep quality, and life quality in general. The sleep and life quality of patients suffering from endometriosis is poorer than in healthy women. The main cause of sleep disturbances is pain and nocturia, but some researchers indicate that sleep insufficiency can in turn increase inflammation processes and worsen the pain. A similar pathophysiological mechanism can cause psychiatric disorders [11]. The most frequently used imaging modality in BE and EVUP is transvaginal ultrasonography (TVS) (Figure 2). Besides TVS, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), transabdominal ultrasonography (US), or cystourethroscopy are used as supplementary imaging methods for those conditions [3, 10]. Surgical resection of endometrial foci is a gold standard therapy, which enables/makes it possible to completely treat the disease [3, 7, 12]. Surgical removal may be done by laparotomy, laparoscopy, or using a surgical robot. Apart from surgical resection, pharmacotherapy plays a key role in BE, leading to clinical improvement [3, 7]. Several treatment options such as progesterone-based therapy, combined oral contraception, and GnRH analogues are available. In our study we have decided to analyse the variety of symptoms and the outcomes of laparoscopic surgery done on BE and EVUP patients.

Material and methods

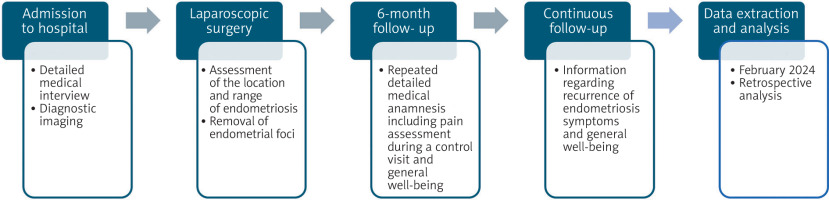

A retrospective cohort study was conducted including the patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery due to BE and/or EVUP in the gynaecological clinic in the tertiary hospital in central Poland in 2017–2023 (n = 29). The data was collected and extracted from patients’ history of disease in February 2024. Data extracted from patients’ history included their age at the moment of the operation, number of pregnancies, type of delivery, history of miscarriages, use of hormonotherapy, location of endometriotic lesions, and surgical procedure type. The endometriosis foci location was diagnosed mainly by using TVS, only 1 patient was additionally diagnosed by using MRI. Moreover, it contained detailed patient histories with information about the symptoms and their severity taken on the day of admission to the hospital. The pain intensity was evaluated with the visual analogue scale (VAS). Visual analogue scale is a 10-grade scale, which is used for patients in self-assessment of pain. Visual analogue scale range is 0–10 points. A 0-point score resembles/means no pain, and a 10-point score reflects the worst pain imaginable. Visual analogue scale result of 1–3 indicates mild pain, 4–6 points moderate pain, and a score 7–10 highlights/demonstrates shows severe pain. Six months after the operation, 18 patients had follow-up visits, 10 of them had BE and 8 – EVUP. The patients were asked again about the intensity and type of pain they have experienced after the operation. Additionally, patients were asked about the frequency of urinary tract infections and urinary incontinence before and after the surgery. Moreover, the patients answered questions about a possible recurrence of endometriosis symptoms and their general well-being during routinely planned continuous follow-up (Figure 3).

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 13.1 software. The descriptive statistics were used. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. The continuous variables were presented as medians and interquartile ranges. The Wilcoxon matched-pairs test was performed to analyse if the pain changes after the surgery are statistically significant. The outcome/value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

29 women with BE (n = 12) or EVUP (n = 17) were included in the study. The mean age of women who were operated on was 35.2 ±6.5 (min. 20, max. 48). There were 14 nulliparas, 5 primiparas, and 4 multiparas. The percentage of patients who had a CS was 13.4% and those who delivered through vaginal labour was also 13.4%. Among this group of patients, no miscarriages were reported (Table 1).

Endometriosis location

In our study there were no isolated EVUP cases, nevertheless, EVUP most often occurred together with ovarian endometriosis (n = 11) or endometriosis in the uterosacral ligaments (n = 10). The other locations of endometriosis associated with EVUP were the uterus, bowels, fallopian tube, and vagina (Table 2). Bladder endometriosis occurred in 12 cases and was isolated only in 5 patients. In 7 cases BE occurred concomitantly with other types of endometriosis, the most common being adenomyosis (n = 4) and peritoneum (n = 2). The other locations were uterosacral ligament, fallopian tube, and ovary. In 2 cases the concomitant presence of BE and EVUP was observed (Table 3).

Table 2

Location of endometriosis lesions

Table 3

The changes in bladder endometriosis symptoms after the surgery

Pre-operation period

Only 3 patients were treated with preoperative hormonotherapy, in 2 cases dienogest was prescribed, and one patient received oral contraception with combined oestrogen and progesterone. The reason for preoperative hormonotherapy was lack of compliance or it was prescribed by the attending gynaecologist. All the patients were qualified for laparoscopic surgery (n = 29, 100%), although in 2 cases it was decided to switch to laparotomy (Table 4). The laparotomy was necessary due to the damage of the ureter during operation in one case and due to vastly extended endometriosis in the second/other one. Additionally, the surgical procedures performed included ovarian cystectomy (n = 14), salpingectomy (n = 3), adnexectomy (n = 2), myomectomy (n = 2), and focal endometrial resection of the vesicouterine pouch (n = 17), uterosacral ligaments (n = 11), the Douglas pouch (n = 1), round ligaments of the uterus (n = 1), rectovaginal septum (n = 1), partial resection of the rectum (n = 3), and sigmoid colon (n = 1). For bladder endometriosis, the operations included transmural resection of endometrial foci on the anterior bladder wall (n = 2) and posterior bladder wall (n = 10). The largest endometriotic lesion measured 6 cm in diameter. Peritoneal adhesions were also removed during the operations.

Table 4

The changes in vesicouterine pouch endometriosis symptoms after the surgery

Follow-up

Ten patients with BE and 8 with EVUP have taken part in the follow-up. Before surgery the BE patients suffered from dysuria (100%), dysmenorrhea (60%), intramenstrual pain (50%), dyspareunia (40%), and one patient had dyschezia (10%). In contrast, the most common EVUP symptom was dysmenorrhea (75%) and intramenstrual pain (75%), and other symptoms were dyschezia (37.5%), dyspareunia (25%), and none of the patients suffered from dysuria (0%) (Table 5). The main symptom of BE was dysuria, which significantly improved after the surgery (2–10 IQR vs. 0–2 IQR; p = 0.005), as well as dysmenorrhea (0–10 IQR vs. 0–2 IQR; p = 0.043) and intramenstrual pain (0–10 IQR vs. 0–2 IQR; p = 0.043). Additionally, the patients suffered from dyschezia (0–9 IQR vs. 0 IQR; p = 0.180) and dyspareunia (0–8 IQR vs. 0–2 IQR; p = 0.068), however, the postoperative improvement was not statistically significant (Table 3). Before the operation, haematuria was observed in one patient with BE, whereas 4 other patients suffered from frequent urination. Additionally, patients after BE surgery reported limitation in occurrence/reduction of urinary tract infections and improved well-being in the form of improved mental health and better sleep quality. The recurrence of dysuria was observed in 25% (n = 3) of BE patients after an average time of 28 months.

Table 5

Comparison of the clinical presentation of the bladder endometriosis and vesicouterine pouch endometriosis

In the group of EVUP patients, statistically significant changes were observed in/for dysmenorrhea (4–10 IQR vs. 0–6 IQR; p = 0.012) and intramenstrual pain (3–8 IQR vs. 0–3 IQR; p = 0.012). Other EVUP symptoms such as dysuria (0–6 IQR vs. 0), dyschezia (0–10 IQR vs. 0–8 IQR; p = 0.068) and dyspareunia (0–10 vs. 0–5; p = 0.109) had a postoperative improvement, but were not statistically significant.

Discussion

Here we report that despite the similar location of endometriosis infiltration, the symptoms, diagnosis and treatment options vary significantly (Table 5).

In this study, the mean age of all patients who were included was 35.2 ±6.5 years. Similar age of patients was reported by other researchers in their studies about BE, such as Piriyev et al. (35.03 ±6.3), Hirata et al. (38.6 ±6.3), Gabriel et al. (32.3 ±6.4) [13–15]. Moreover, in a study published by Piriyev et al., only 18% of patients had a history of pregnancy, whereas Hirata et al. included 32.5% of women with this data/a history of pregnancy [13, 14]. In our analysis the structure of parities is similar, 69.0% of patients were nulliparous, and only 31.0% of women have been pregnant before. Even though, the iatrogenic theory of BE origin claims that the previous CS can lead to the development of BE due to the spread of endometrial cells and tissue during operation, we did not observe any increase in BE in women after CS. What could have had an impact on this was the fact that during the CS these patients underwent, no harming of the urinary bladder was noted and a small group of patients was analysed. Priyev et al. have also reported only 6% of patients with BE who underwent CS, and 12% – with a history of vaginal delivery [13].

Concomitant BE occurs more commonly than the isolated form, which was reported by other researchers. Hirata et al. have shown that 47.4% of patients had a concomitant BE, with the most common extravesical endometriosis being an ovarian endometriosis [14]. In our study, the most common extravesical endometriosis form was associated with the uterus (33.3% of BE patients), such as adenomyosis, while the ovaries were involved only in one case (8.3% of patients with BE). From our study it can be seen that EVUP tends to occur more frequently than BE (58.6% of patients suffered from EVUP), which was also observed by Da Araujo et al. in their study [16]. Additionally, similar observations were presented by Holland et al. in their study, which showed that vesicouterine fold DE (n = 6) was more common than BE (n = 5), and EVUP in 83.3% of cases was concomitant with other endometriosis locations [17]. We have observed that EVUP occurred only concomitantly with the most common types being ovarian endometrioma, which affected 64.71% of patients, and endometriosis of uterosacral ligaments, which affected 58.82% of patients. Da Araujo et al. have also observed that the ovarian endometrioma is co-occurring more often with EVUP than BE (30.9% vs. 16%), which was confirmed in our study as well (64.7% of EVUP cases vs. 8.3% of BE cases) [16].

Despite the rarity of BE, the diagnosis should be considered when recurrent urinary tract infections, urinary incontinence, and/or dysuria are noted by the patient. Hirata et al. showed that the most frequent symptoms of BE were dysmenorrhea (56.2%) and dysuria (55.1%), which were similar to frequency of our patients’ preoperative symptoms [3, 14]. In another study, Gabriel et al. outlined that dysuria, haematuria, and urinary tract infections are more common among the patients with BE compared to the patients with extravesical endometriosis (49% vs. 13%, 12% vs. 0%, and 18% vs. 4%; p < 0.001) [15]. Kovoor et al. in their study presented that mean pain score (when evaluating the severity of dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia) was statistically significantly lesser/lower two months after the laparoscopic surgery (7.8 vs. 2.7, and 5.6 vs. 1.6, respectively, p < 0.002), and then twenty months later (7.8 vs. 3.2, and 5.6 vs. 1.8, respectively, p < 0.000) [18]. Yılmaz et al. have also shown that the most common symptoms were dysuria (94%) and dyspareunia (76%) and that after a laparoscopic surgery, the pain severity decreased during the six-month postoperative period. Additionally, in the same study, the postoperative pain intensity was significantly lower than the preoperative pain 5–2 in VAS score (p < 0.0001) [10]. In our study, among 10 patients with BE, median VAS values were 9 for dysuria and 5.5 for dysmenorrhea (p = 0.005 and p = 0.028). Whereas in 8 patients with EVUP, the most common symptoms before surgery were dysmenorrhea and intramenstrual pain, with VAS of 8 and 5, respectively (p = 0.012 and p = 0.012). After the surgery, there was no pain reported in both groups of patients. Cheng et al. in their case report have also shown that before surgery patients with EVUP invading bladder had severe dysmenorrhea and dyspareunia, while after the surgery they have noted that the symptoms have fully subsided [19]. Hirata et al. analysis showed that haematuria affected 42.7% of patients with EVUP, while in the study of Kovoor et al. only 14.7% of patients had haematuria. Even though in our study this symptom was only reported by a single patient (3.45%), haematuria also diminished after the surgery [14, 18].

Numerous analyses of DE imaging methods are available in the literature. Guerriero et al. performed a systematic review with patients who underwent TVS before surgery, showing sensitivity of 62% and specificity of 100% for this diagnostic method [20]. Transvaginal ultrasonography is a reliable first-line imaging modality for the diagnosis of endometriosis involving uterosacral ligaments, rectovaginal septum, vagina, and bladder, particularly in patients with controlled pain and absence of intestinal stenosis or ureteral involvement [21]. Transvaginal ultrasonography can also be used for the follow-up of patients with ultrasonographic diagnosis of DE, whose symptoms have subsided during the medical treatment, or for those trying to become pregnant [20]. Holland et al. proved that the location of endometriosis lesions affect the diagnostic accuracy of TVS, obtaining the sensitivity and specificity of 100% for patients with BE, and only 16.7% sensitivity for patients with EVUP (specificity remained at 100%) [17]. High accuracy of the US in diagnosing BE was also shown in several other studies [22, 23]. In order to assess the extent of the endometriosis lesions in more detail, MRI can be chosen as a supplementary imaging modality. It is characterized by high accuracy for detecting endometriosis lesions and particularly foci hidden beneath healthy tissue or obliterated Douglas pouch [24].

Painful bladder syndrome together with chronic pelvic pain, in women with DE, is detrimental to the overall sleep quality. In the study by de Souza et al., it was determined that only 13% of women with DE had a good sleep index, whereas 90.5% of women with moderate/severe pain noted poor sleep quality [25]. Cosar et al. found that 80% of patients with chronic pelvic pain experienced reduced sleep quality. [26]. Sleep quality in women with endometriosis can be connected with pain intensity, type of pain, mental health detoration/deterioration and nycturia. Higher pain intensity in women with DE amplifies the risk of insomnia 2.8 times [25]. Patients who suffer from endometriosis note a considerable difference in their quality of life after the surgery: improvement is seen in all areas of life, including sleep quality, feeling of fatigue and sexual functions.

Laparoscopic surgery is an effective way to treat BE and EVUP. In BE, there are three commonly performed surgeries: excision of the nodule, partial cystectomy, and transurethral resection of the nodule [27]. The recurrence of BE after the laparoscopic surgery is very rare, in Priyev et al. analysis, no patients (from 25) were found to have new foci of BE [13]. Similarly, in Rocha et al. case series, no BE (n = 27) recurrence after the laparoscopic removal was observed [27]. In our study we have observed recurrence of endometriosis in only 3 patients during the follow-up period. In contrast, in the study of Hirata et al., the recurrence after the laparoscopic partial cystectomy was higher than after an open partial cystectomy (3/24 vs. 0/20 patients), but the results were not statistically significant (p = 0.0879) [14]. Despite the fact that the main technique in managing endometriosis is conventional laparoscopy, in recent years robotic surgery has gained popularity, and as several studies highlight, robotic surgery shows promising results [28]. It is used in more complicated procedures, when extensive urological lesions, intestinal involvement, or widespread peritoneal lesions are observed. Bandala et al. showed in their study that patients treated with robotic surgery required fewer days in the hospital than patients treated by conventional laparoscopy. However, Nezhat et al. presented opposite findings, noting longer hospital stays after robotic surgery [29, 30]. Moreover, the same study showed that patients who underwent robotic surgery had a lower frequency of postoperative pain, which was not confirmed in other studies [31]. Due to the existence of contradicting results, more research is needed to determine robotic surgery’s role in the treatment of endometriosis.

Medical therapies, including combined hormonal contraceptives and progestogens, such as dienogest, are considered a first-line pharmacotherapy in DE, which efficacy has been demonstrated in the literature. It is also an alternative treatment for patients who are not planning to conceive or cannot undergo surgery [32, 33]. Westney et al. showed that after treating 13 patients with low-dose monophasic oral contraceptives, complete resolution of symptoms was reached in 92% of patients [34]. Nagashima et al. showed that after 3 months of dienogest administration, the size of BE lesions significantly decreased, and the reduction was sustained 48 months afterwards. Moreover, all patients treated with dienogest have experienced alleviation of urinary symptoms during long-term therapy until menopause [33]. Another pharmacological approach to treating endometriosis involves the use of GnRH analogues, which include both antagonists and agonists. In clinical practice, non-peptide, small-molecule GnRH antagonists such as elagolix, relugolix, and linzagolix are commonly used. Linzagolix is the newest drug in this group, and its effectiveness is dose dependent. Notably, results from the phase III EDELWEISS 3 study demonstrated that treatment with linzagolix combined with add-back therapy led to significant improvements in both dysmenorrhea and non-menstrual pain compared to placebo [35]. Moreover, oral contraceptives and GnRH agonist were proven to reduce symptoms and decrease the size of lesions within 6 months of administration [36].

Endometriosis is a benign condition, which has a very low risk of transforming into UTE malignancy. Only a few cases have been reported in the available literature and the most common site of endometriosis-associated malignancies was the urinary bladder [30]. There were no malignancy transformations reported in patients included in the study. The main limitation of this observation is a short follow-up period.

Conclusions

Our study shows that BE and EVUP symptoms were significantly different, despite the similar endometriotic lesion location. Another differentiating feature of both analysed endometriosis types was the fact that EVUP more commonly appears as a concomitant form of endometriosis when compared to BE, which usually appears to be isolated. Additionally, development of dysuria in EVUP patients might suggest its spread and the development of BE. The history of having CS was not found to be a significant risk factor for BE development. Laparoscopic surgery is an effective and reliable way of endometriosis management for both BE and EVUP patients. Moreover, the pain relief always improves patients’ quality of life. Bladder endometriosis and EVUP treatment can be carried out by a gynaecologist, however, a cooperation with a urologist is crucial for the successful management, especially when there is a ureter infiltration.