Cyclosporine: history, and importance

The scientific community’s emphasis on bacteria, fungi, and various other microorganisms, was heightened in the 20th century. One of the drugs that played a pivotal role in exacerbating some of these life-threatening affli-ctions was the fungus metabolite cyclosporine (CsA) [1]. CsA was discovered in 1973 by Sandoz [2]. The prime goal was to investigate isolated compounds from the ascomycete fungus Tolypocladium inflatum, which were proven effective fungicides against phytopathogenic fungi [3].

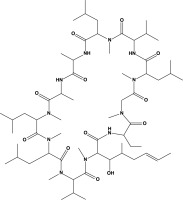

From the chemical perspective, CsA is a cyclic, lipophilic peptide composed of 11 amino acids. Its molecular weight is 1,202 Da, and its molecular formula is C62H111N11O12 [3]. In its pure form, the drug appears as a white powder. Figure 1 shows a structural representation of the molecule.

CsA has become a well-known and widely used medication. A decade after its discovery, in 1983, led by the European trials, the drug received its initial approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [4, 5]. CsA has evolved into a leading immunosuppressant through continued research and practical application.

CsA is widely used as an immunosuppressant in organ transplantation to improve graft survival and prevent tissue rejection. Additional applications in treating severe rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus ery-thematosus, psoriasis vulgaris, and other autoimmune diseases are well established [4, 5]. Despite its success in reducing acute rejection and enhancing short-term graft survival, CsA’s long-term use has revealed nephrotoxic effects, contributing to concerns about sustained graft viability [4, 5].

Precise molecular mechanisms and modes of action of CsA are not easy to identify [6]. It has been reported that T-lymphocytes are cellular targets for CsA. For them to be activated, macrophages need to release interleukin (IL)-1. The mechanism of CsA involves suppressing the release of IL-1 from macrophages, and additionally preventing the proliferation of T-lymphocytes through suppression of IL-2 [4, 5].

Various aspects of CsA have been well explored over the years, and the role of CsA as an immunosuppressant and calcineurin inhibitor is well established. The role of CsA in cancer research and its potency as a cancer suppressor have not been fully elucidated. The exact function of CsA as an anti-cancer agent, and the role of CsA in combination with other therapies against various malignancies, are only partially explored. It is evident from the literature that the role of CsA varies from a suppressor of different oncogenes in malignancies to a promoter of skin cancer.

The current review summarizes the current knowledge of CsA in cancer research including its ability to overcome drug resistance, especially when formulated in nanomedi-cines.

Literature search

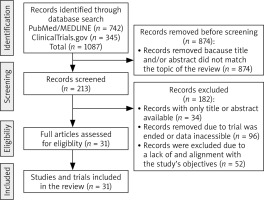

During the initial phase, we conducted a comprehensive search of the PubMed/MEDLINE database to gain a gene-ral understanding of the topic (Fig. 2). No specific filters were applied during this search. In the subsequent phase, the search was refined to include specific scientific terms, such as “ciclosporine”, “cyclosporine”, “CsA”, in combination with keywords, such as “tumor”, “cancer”, “anticancer”, “antitumor”, “neoplasia”, “leukemia” ”melanoma”, “carcinoma”,” bladder cancer”, ”breast cancer”, “kidney cancer”, ”lung cancer”, ”lymphoma”, ”colorectal cancer”, ”pancreatic cancer”, ”bladder cancer”, ”thyroid cancer”, ”uterine cancer”, ”oral cancer”, ” thyroid cancer”, “glioma”, or “treatment”. Besides PubMed/MEDLINE, clinical trial databases such as clinicaltrials.gov were searched similarly. The latest literature search was conducted in March 2024 (Fig. 2). Only relevant studies that examine the direct or adjuvant effects of CsA were included in the current review (Fig. 2). We included only literature published in the English language. Non-English papers were not considered.

Results

Cyclosporine A as a “cancer-causing” agent

Cancer, being vigilant by nature, awaits an opportunity to invade the cells, tissues, and organs of individuals with an impaired immune system [7]. Organ transplantation is one such infrequent instance, largely attributable to immunosuppressive protocols employed during implantation that lead to immune system impairment [8]. Immune surveillance mechanisms of the recipient are almost completely compromised, which opens a window of opportunity for cancer to invade cells [8]. Although the risk associated with cyclosporine is evident, it remains unclear whether CsA bears responsibility for instigating cancer proliferation and development [8].

Over the years, to explore the potential of CsA in cancer research, groups observed different effects following the administration of CsA, in both in vitro and in vivo studies. In 1999, Hojo and his group suggested that immunosuppressants, including CsA, promote cancer progression directly and completely independently of the suppressed immune cells [9]. They found an increase in the number of renal carcinoma metastases by almost 50% in mouse models treated with CsA [9]. In the case of Lewis lung carcinoma cells, pulmonary metastasis doubled in size [9]. However, all these experiments were conducted only in a controlled laboratory environment using murine models [9].

Different results are obtained when experiments are moved from the controlled laboratory environment to clini-cal practice [10]. As a rebuttal to the study from Hojo in 1999, Robert Landewé and his group examined the effect of CsA on rheumatoid arthritis patients and the risk of developing malignancies [10]. Patients who were treated with CsA for less than a year had a higher risk of deve-loping cancer [10]. However, for patients who were treated for more than a year, the risk of developing cancer is equivalent to the standard cancer incidence in the population [10]. Similarly, other reports indicate no carcinogenic effects for short-term CsA treatment [11]. This means that the duration of the treatment is a key aspect of the development of CsA-related malignancy [11].

In another study, the group examined a cohort of 272 patients with various skin diseases (psoriasis, palmoplantar pustulosis, atopic dermatitis, and eczema), treated with CsA for a median of eight months [12]. Malignancies were diagnosed in 13 patients (4.8%), while only three patients were treated exclusively with CsA for more than 12 months [12]. Among those who had developed cancer (carcinoid tumor, lung cancer, and prostate cancer), only four were treated with CsA for longer than 12 months [12]. The percentage of people developing cancer was far lower than that of the general population [12]. Further, in the meta-analysis from 2020, out of 365 assessed studies regarding psoriasis and cancer prevalence, 112 studies were included in the final analysis [12]. The prevalence of cancer in patients with psoriasis in the general population was around 5%, the same as in the control group [12]. This evi-dence supports the conclusion that the obtained results are unrelated to CsA treatment [12].

A study that has the same implications involved CsA blockage of apoptosis through inhibition of the DNA binding activity of the transcription factor Nur77 [13]. The effects of Nur77 on cancer are complex, as it sometimes acts as a tumor suppressor and occasionally as a promoter of cancer growth, depending mostly on the cellular context, tissue type, signaling pathways, and several other factors involved [13]. The group reported that CsA inhibits TCR (T-cell receptor)-mediated activation of Nur77 by blocking its DNA binding activity, likely through the N-terminal region of the protein [13]. However, the overall impact of TCR- mediated apoptosis in cancer is complex and can be influenced by various factors related to the tumor type, the immune microenvironment, and the presence of immune evasion mechanisms [13]. Conversely, multiple groups reported stimulated apoptosis upon treatment with CsA, as in the case of lung adenocarcinoma and prostate cancer [13].

Even though it is commonly claimed that CsA increases the risk of skin cancers, lymphomas, and leukemias, we can confidently state that the data are not sufficiently conclusive. The precise effects are yet to be determined, especially in the light of several reports describing opposite results [56, 65].

However, CsA may be toxic to the higher eukaryotic organisms [14]. The toxicity of CsA used in high concentrations has been confirmed in mouse models [14]. At doses of 50–200 mg/kg/d, the agent can cause neurotoxicity, as well as disorganization of the spleen, lymph nodes, and thymus [14]. Weight loss and diarrhea are also among the commonly reported side effects of higher doses [14]. In the case of 12.5 mg/kg/d and lower concentrations, no side effects were reported [14].

Role of cyclosporine A in cancer prevention

CsA effect in cancer cell lines

The first reports on the observed cytotoxic effects of CsA on the neoplasm date back to the late 1980s [15].

The majority of existing studies investigating the role of CsA predominantly employ cancer cell lines as their primary research model. In vitro methods remain fundamental due to their non-invasive nature, cost-effectiveness, and convenience for observing the effects of treatments. However, these methods serve primarily as an initial step for understanding the specific treatment’s impact. A notable study conducted in 2012 by Werneck et al. [16] demonstrated reduced growth of CACO-2 (colon adenocarcinoma) cell lines when treated with CsA. While the exact mechanism behind this reduction was not determined, the study also observed a significant decrease in cell growth in esophageal adenocarcinoma cell lines treated with CsA [16]. Furthermore, research by Masuo et al. [16] indicated that CsA suppresses the growth of colon cancer cell lines by inhibiting cell cycle progression. This inhibition is achieved through reduced expression of PCNA and c-Myc, and increased expression of p21 [16]. These findings suggest that while general administration of CsA may have substantial drawbacks, overall immunity will not be compromised [16]. This approach has potential implications for disrupting the suppressor function of regulatory T-lymphocytes in tumor tissues [16].

To achieve the desired outcomes, precise dosing of CsA is crucial. While CsA has been observed to enhance the transcription of transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGF-b1) in various cells, the underlying mechanisms and the involvement of calcineurin were not fully explicated. This investigation specifically investigated the regulation of TGF-b1 in normal human lymphocytes and cell lines, focusing on Jurkat T cells (immortalized human T-lymphocytes) and A549 lung carcinoma cells [17]. In Jurkat T cells, the activation of the TGF-b1 promoter involved calcineurin and the transcription factor NFATc, with CsA and FK506 acting as inhibitors of this activation [17]. However, A549 cells exhibited insensitivity to these drugs [17].

In human T cells preactivated with phytohemagglutinin, CsA and FK506, even at concentrations inhibiting IL-2 production, did not significantly impact TGF-b1 biosynthesis induced by the T cell receptor (TCR) or TGF-b receptor [17]. Remarkably, pre-treating fresh lymphocytes with CsA or FK506 during primary TCR stimulation resulted in reduced TGF-b1 production during secondary TCR activation [17]. At higher concentrations (10 mM), equivalent to what is used in rodent experiments, CsA induced apoptosis in T-lymphocytes and released preformed, bioactive TGF-b1, a phenomenon not observed with FK506 [17]. These findings suggest that CsA and FK506 do not exhibit uniform induction of TGF-b1 biosynthesis, and their effects are contingent on the cell type and drug concentrations employed [17]. Consequently, this challenges the observation of a consistent response across diverse cell types, emphasizing the need for a balanced consideration in utilizing these immunosuppressive agents [17].

Further, in another study from 2012, it was reported that CsA downregulates tumor-specific isoform of the enzyme pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) in breast cancer [18]. As PKM2 is highly expressed in breast cancer cell lines, the group examined levels of PKM2 after treatment with CsA in MCF-7, MDA-MB-435 (subsequently confirmed to be a me-lanoma cell line), and MDA-MB-231 cancer cell lines [18]. CsA is an effective inhibitor of kinase M2 activity and, therefore, the proliferation of breast cancer cell lines [18]. In another study, treatment of both estrogen receptor (ER)+ and ER– breast cancer cell lines with CsA was demonstrated to inhibit the growth and progression of malignancy [19]. These results present valuable insights into the understanding of chemotherapy-resistant tumor types and potential novel therapeutic approaches [19].

In bladder cancer cell lines, the immunosuppressants tacrolimus and CsA were used as treatment options, and significant suppression of malignancy was observed [20]. The primary mechanism is achieved through downregulation of NFATc1, and in the future it may act as an active therapeutic agent, as NFATc1 plays an important role in bladder cancer progression [20]. The same effect was observed for in vivo murine models, with significant tumor retardation in the case of CsA [20]. Using the same approach, Sakai and his group examined the effect of tacrolimus and CsA on hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines [21]. Both immunosuppressants suppressed the growth and invasion of the malignancy, but tacrolimus was more effective [21]. The mechanism behind growth suppression was not described in the study [21].

Human malignant gliomas are among several cancer types that are resistant to current therapeutic approaches, primarily chemotherapies [22]. Therefore, a common approach is to investigate other drugs to sensitize malignancies to treatment [22]. Immunosuppressants such as CsA have been shown to inhibit growth and induce cell death in glioma cancer cells [22]. One of the most extensive studies on CsA’s anti-tumor activities was conducted by Munoz and his group [22]. They examined the anti-tumor action of CsA on seven human cancer cell lines, including GAMG glioma, SW-403 colon carcinoma, 23132/87 gastric carcinoma, WERI-Rb-1 retinoblastoma, SKN-BE(2) neuroblastoma, HEp-2 laryngeal carcinoma, and CAPAN pancrea-tic carcinoma [22]. Apoptosis was observed in all seven cancer cell lines following the administration of CsA [22].

In addition to inducing apoptosis, CsA also affects tumor proliferation by restoring the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21WAF1/CIP1, a crucial regulator of the cell cycle. CsA stimulates the expression of p21WAF1/CIP1, thereby negatively impacting tumor proliferation and the survival of cultured malignant cells [23]. This effect was also observed in pituitary gland GH3 cells, where CsA treatment induced both apoptotic and autophagic cell death [24]. Although the exact mechanism was not fully elucidated, the results suggest that CsA’s induction of cell death highly correlates with Bcl-2 and Mn-SOD levels [24].

Ciechomska and her group reported that CsA treatment of glioma cells led to the inhibition of NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T cells) signaling, activation of TP53/p53 and MAPK1/2 (ERK) signaling, and accumulation of the cell cycle inhibitor CDKN1A/p21CIP1/WAF1 [25]. They also found that AKT1 signaling was downregulated, while Faslg/FasL was activated [25]. Another mechanism by which CsA suppresses glioblastoma is by reducing IL-8 mRNA levels, as glioblastoma relies on IL-8 for its progression [25]. Following CsA treatment, these levels significantly decrease, contributing further to the suppression of glioblastoma [25].

CsA triggers apoptosis even in chemotherapy-resistant drugs, positioning it as a high-priority treatment option that may be applied for other resistant cancer types such as breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, small cell lung cancer, melanoma, and sarcomas [26].

CsA as an adjuvant therapy

Combining CsA with other therapies is a promising tool in targeted treatments. Such examples include the usage of CsA as adjuvant therapy in combination with crizotinib, doxorubicin, nimustine, carmustine, and several other treatments [27].

Crizotinib, despite being a potent treatment for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), has a limited effect when it comes to tumor suppression. Crizotinib activates Erk1/2 and Ca2+-calcineurin (CaN)-kinase suppressor of Ras 2 (KSR2) signaling [28]. As a result, this leads to augmented survi-val of malignant cells [28]. However, once CsA is combined with crizotinib, both signaling pathways are blocked [28]. The synergistic effect of crizotinib with CsA significantly increases the anti-tumor effect of the drug for NSCLC and other malignancies [28]. The observed effect was documented in both in vitro and in vivo experiments [28]. In the same way, CsA increases the anti-cancer effect of gefitinib for NSCLC cell lines. The proposed mechanism for induced apoptosis is through the inhibition of STAT3 [29].

The combination of CsA with some toxins, such as immunotoxins (IT), increases the apoptotic index [30]. The synergistic effect was so strong that metastasis inhibition was observed also in rat cervical cancer models [30]. Most importantly, median survival for the animals treated with combined therapy significantly increased [30]. The reported effect was observed in multiple cancer lines treated alone with CsA; however, the percentage of apoptotic cells doubled once IT was combined with CsA [30]. When used alone, IT triggers three times fewer apoptotic cells compared with CsA [30]. Both in vitro and in vivo studies produced similar results [30].

Doxorubicin is a type of chemotherapy drug that slows/stops the growth of cancer cells by blocking the enzyme topoisomerase II and is commonly applied for breast, ova-rian, bladder, and thyroid cancers [27]. However, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) does not respond to doxorubicin [27]. To overcome resistance to the drug, Kim et al. [27] sought to examine the effect using the combination of verapa-mil, tamoxifen, and CsA. An in vitro approach was used, and once the combination of the drugs was applied to the HCC cell lines, the resistance persisted [27]. However, a combination of CsA and tamoxifen reduced IC50 of doxorubicin by up to a factor of 3.9 and therefore made HCC more sensitive to the chemotherapy [27]. A similar effect was observed for the combination of all three drugs [27]. The synergism of CsA, tamoxifen, and verapamil is yet to be observed in clinical trials [27].

The effect of chemotherapeutic drugs used against gliomas, such as ACNU (nimustine), BCNU (carmustine), and hydroxyurea, can be significantly improved once combined with CsA [31]. Pyen and his group examined synergistic effects on glioma cell lines; a noteworthy cytotoxic effect was observed, and there was dose-dependent inhibition of DNA synthesis [31]. Han and his group examined the synergistic effect of CsA and cisplatin on glioma cell lines [32]. In combination the drugs induced apoptosis, as a result of increased ROS generation and decreased intracellular glutathione levels [32].

Another notable observation is that the administration of a chemosensitizer in a low concentration (0.04 µg/ml) may cause secondary resistance of cancer to CsA and its derivatives such as cyclosporine H (CsH) [33]. The observed effect was precisely noted in the leukemic cell line F4-6RADR-CsA with a CsA concentration of 0.04 µg/ml, administered over some time [33].

A malignancy with a high mortality rate and poor prognosis for which CsA has shown excellent results is oral squamous cell carcinoma [34]. The most prevalent type of oral cancer is primarily associated with smoking, with HPV pathogenesis also playing an important role in a significant proportion of cases [34]. Besides this, multiple groups have reported lower apoptosis rates for this oral cancer [34]. However, following the administration of CsA, the apoptotic process and suppression of cell cycles may be recovered [34]. To suppress growth of the cells, a CsA concentration of 1 µg/ml is sufficient [34]. No cancer cell growth is observed once a concentration of 2 µg/ml is administered [34].

CsA-containing nanomedicines in anti-cancer therapy

Any chemotherapeutic agent’s effectiveness depends on its ability to reach the tumor tissue, wherever it may reside within the body, and accumulate at sufficient concentrations to exert its pharmacological activity. Typically, nanoformulations containing the active drug (s) and a suit-able delivery system in the nano size range (termed nanoparticles or nanomedicines) are usually needed to improve the bioavailability and effectiveness of an active agent, especially if they are hydrophobic and have a large molecular weight [35]. Nanoformulations can, for example, improve the solubility of poorly soluble drugs such as CsA and other anti-cancer agents, protect the drug from degradation in the harsh biological milieu, overcome drug efflux transporters (see discussion below), enhance cell uptake and intracellular bioavailability of drugs, and provide slow or sustained release of drugs to either local or systemic sites [35, 36]. Some reports on nanomedicines or nanoformulations containing CsA for cancer chemotherapy, particularly in overcoming drug resistance, have appeared in the literature. Some of the key studies are discussed below.

Since CsA is a lipophilic drug with relatively poor aqueous solubility/oral bioavailability, a narrow therapeutic index, and the potential to induce nephrotoxicity, the design of a safe, effective, and non-toxic nanoformulation would be clinically desirable in cancer chemotherapy. Oral admini-stration would be ideal because of its ease of administra-tion and patient acceptability. For its use as an immunosuppressant, CsA-containing soft gelatin capsules and emulsion-based oral delivery systems are commercially available [37–39]. The first registered formulation (Sand-immune, Novartis, Switzerland) was a simple oil-in-water emulsion preconcentrate comprising corn oil and alcohol. However, this formulation had a bile-dependent absorption profile that led to significant intra- and inter-individual variability. Thus, a new formulation (Neoral, Novartis, Switzerland) was launched onto the clinical market more than a decade after Sandimmune. The newer formulation was a microemulsion with water that did not require the action of bile, thereby providing improved and more consistent bioavailability [38, 39]. However, Neoral and the intravenous formulation of CsA contain the non-ionic solubilizing and emulsifying agent Cremophor RH 40, which can cause anaphylactic reactions in some patients [38, 39]. Thus, newer formulations without this emulsifying agent have been produced commercially [37–39]. More recently, multi-ple delivery systems and nanoformulations ranging from micelles and liposomes to polymer-based nanoparticles have been explored for CsA in preclinical studies [37–39], but only a few have been reported in the context of its anti-cancer applications.

In a study designed to improve the antitumor efficacy of CsA in breast cancer, its entrapment within a chitosan- membrane-based delivery system (that could potentially be employed as a sub-cutaneous implantable device) was found to markedly enhance CsA activity in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells in vitro [40]. No animal experiments were reported in this proof-of-concept study. Thus, in the absence of extensive in vivo testing, it is not known how efficacious this delivery system would be if administered subcutaneously in breast cancer patients.

In addition to its innate anticancer actions, CsA is well known to reverse drug resistance in several cancer cell types through its ability to inhibit efflux transporter mole-cules such as p-glycoprotein (P-gp) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) [41]. The expression of such efflux transporters on cancer cells results in multiple drug resistance by preventing the intracellular accumulation of a diverse range of anti-cancer agents, including taxanes, vinca alkaloids, and anthracyclines such as doxorubicin [35]. The intrinsic ability of CsA to reduce the expression and/or function of efflux transporters has been exploited in seve-ral nanoparticle formulations/nanomedicines designed to sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapeutics agents that otherwise would be resistant [35]. The co-entrapment of CsA and doxorubicin, an anthracycline antibiotic that is a substrate for P-gp, into a stable, long-circulating liposomal formulation effectively improved the efficacy of doxorubicin in MCF-7 breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo [42]. Similarly, co-delivery of the same two drugs in another nanoformulation, comprising photoluminescent graphene quantum dots encapsulated in mesoporous nanoparticles, significantly improved the anti-cancer actions of doxorubicin in lung cancer cells [43] and also when co-delivered in polyisobutylcyanoacrylate nanoparticles to drug-resistant P338 leukemia cells [44]. In a model of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) that employed A549 cells in vitro and as xenografts in mice, co-encapsulation of CsA with doxorubicin in biodegradable poly(D, L-lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles effectively inhibited P-gp efflux pump activity and improved anticancer effects in vitro and in vivo [45]: The co-encapsulation of CsA and paclitaxel in a micelle nanoformulation consisting of 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero- 3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)[46] significantly improved the drug’s cytotoxicity in drug- resistant kidney cells, most likely due to CsA-mediated inhibition of the P-gp efflux transporter [46]. A sterically stabilized liposomal formulation of doxorubicin and the CsA analog valspodar, which also inhibits P-gp, also signi-ficantly sensitized drug-resistant MDA435LCC6/MDR-1 human breast cancer xenografts to therapy with doxorubicin [47].

In addition to the surface of cancer cells, P-glycoprotein efflux transporters are also present in other sites within the body, such as the luminal side of the intestinal tract, where they can limit the absorption of several drugs, including anti-cancer drugs such as docetaxel [35, 48]. In an attempt to improve the oral bioavailability of docetaxel, CsA was co-encapsulated with the drug in a self-emulsifying drug delivery system, a nanoformulation that improved the oral bioavailability of the drug by up to 9-fold compared to the free drug in solution and markedly enhanced the in vivo anti-cancer effects in 4T1 breast tumor xenografts in BALB/c mice [49].

Adopting a slightly more sophisticated approach, the co-delivery of CsA in lipid-sodium glycocholate nanoparticles, this time specifically to act as an inhibitor of BCRP, together with a Bcl-2 inhibitor and the anticancer drug mitoxantrone (whose resistance is in part mediated by BCRP and Bcl-2), was shown to be a highly effective strategy to reverse this drug’s resistance in MCF breast cancer cells [50]. A still more complex injectable nanoformulation for photodynamic therapy of breast cancer was developed that contained CsA together with paclitaxel and a photosensitizing agent, chlorin e6 [51]. The active agents (CsA and paclitaxel) were entrapped within albumin nanoparticles that were subsequently coated with liposomal bilayers containing the photosensitizer and tethered transferrin as a targeting moiety to more effectively target and inhibit breast cancer in vitro and in vivo [51].

However, the efficacy of these complex drug-delivery nanosystems in reversing drug resistance might still not be optimal as they largely enter cancer cells by endocytosis, which likely results in CsA being localized in endosomal/lysosomal vesicles well away from the membrane-bound efflux transporters. Thus, it has been suggested more recently that CsA-mediated inhibition of efflux transporters might be optimally achieved through the use of nanoformulations comprising membrane fusogenic lipids that can fuse directly with cancer cell membranes (thereby by-passing endosomal localization) and thereby provide direct local access to the target binding sites located within the transmembrane domains of the membrane- anchored efflux transporters [52].

It is noteworthy that CsA can also reverse the drug resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase (TK) inhibitors such as gefitinib by targeting specific signaling pathways involved in mediating drug resistance in cancer cells [29, 53]. As part of its mechanism of action as an immunosuppressant, CsA inhibits the transcription factor STAT3. This molecule also mediates drug resistance to gefitinib [54]. Thus, the co- encapsulation of CsA and gefitinib within polyethy-lene glycol-block-poly(D, L-lactic acid) nanoparticles effectively reversed gefitinib drug resistance in lung cancer cells by inhibiting the STAT3/Bcl-2 pathway in vitro and in vivo [53]. In another study, the combined delivery of CsA and a newer EGFR TK inhibitor, AZD9291, in nanoparticles composed of chitooligosaccharide (a degradation product of the natu-rally occurring biopolymer chitosan) also improved the therapeutic efficacy of the anticancer agent in a model of human NSCLC [43].

Collectively, these studies not only highlight an alternative method of administration for CsA as nanoparticle formulations but also show that adjunctive use of CsA effectively reverses drug resistance in diverse cancer cells by multiple mechanisms. Thus, its incorporation into nanomedicines might potentially prove to be an effective stra-tegy in cancer chemotherapy.

CsA derivatives

A study by Abdelazem et al. [55] provided new insights into novel therapeutic approaches to CsA. Design and synthesis of CsA derivatives using olefin metathesis chemistry significantly improved the anti-proliferative performance of CsA [55]. The inhibitory effect increased by 80% and 100%, depending on the cell lines [55]. Besides antiproliferative effects, pharmacokinetic properties were significantly better [55]. The distribution of CsA showed particularly promising results in enhancing the treatment of NSCLC in NCI-H226 cell lines [55]. Certainly, approaches like this open a novel gateway for revising the application of CsA and chemical derivatives in cancer treatment [55].

In vivo (clinical) studies

As is evident from the in vitro studies, the potential of CsA in the field of oncology is enormous (the results are summarized in Table 2). We have shed light on its inhibi-tory effects on tumor growth and progression based on a large number of preclinical experiments. In the following pages, we will discuss the application of CsA reported in clinical studies and trials.

Table 1

Overview of diverse effects of CsA on different cancer cell lines

Table 2

Overview of clinical studies utilizing anti-cancer effects of CsA

This section discusses various clinical trials investigating the use of CsA in cancer research, emphasizing its broader significance in various therapies and potential applications. Subsequently, we will provide a comprehensive examination of the crucial role CsA plays in common diseases.

Melanoma, an aggressive skin cancer with a high propensity for metastasis, has been the focal point in research by Selvaggi et al. [56] seeking innovative new therapeutic strategies. The study made significant strides in the the-rapeutic use of CsA in combination with XOMAZYME-Mel (XMMME-001-RTA), an immunoconjugate specifically designed to target melanoma cells [56]. A phase I/II clinical trial aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of repeated doses of XMMME-001-RTA in conjunction with CsA [56]. The trial enrolled nine melanoma patients, who received CsA in divided daily dosages to achieve the desired serum levels [56]. Despite adverse effects such as myalgia, arthralgia, hypoalbuminemia, and mild toxicities, only two patients withdrew due to adverse events [56]. However, the trial yielded promising outcomes: one patient achieved partial lymph node remission for nine months, and another exhibited stable mediastinal disease for 20 months [56]. These findings highlight the potential safety and efficacy of repeated administration of XMMME-001-RTA in combination with CsA in treating melanoma patients [56].

Expanding on this, Liangfeng Gu’s group investigated the effects of CsA in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who had undergone liver transplants, comparing its impact on patient outcomes to that of tacrolimus (TAC) [57]. Both CsA and TAC are immunosuppressive agents, but they function through different mechanisms of action [57]. In terms of immune status, the study found that TAC-treated patients exhibited a marked increase in Foxp3 and CD4 positive cells, indicative of a healthier T lymphocyte-based immune response compared to the CsA group [57]. The TAC group also demonstrated better control of serum calcium levels, potentially mitigating hypercalcemia [57]. CsA inhibits the activity of calcineurin, thereby preventing the activation of T-lymphocytes and the production of IL-2 [57]. On the other hand, TAC also inhibits calcineurin but has been noted to exert stronger suppression of the immune system [57]. In terms of results, the retrospective analysis revealed that TAC significantly improved survival rates, with markedly better outcomes than those seen with CsA at 1-, 3-, and 5-year post-transplant intervals [57]. Short-term follow-up results at four weeks indicated that patients treated with TAC had a 40% remission rate, substantially higher than the 32% remission rate in the CsA group (p < 0.05) [57]. It is noteworthy that CsA exhibits more adverse effects compared with TAC [57]. Patients treated with CsA demonstrated significantly lower left ventricular ejection fraction than those receiving TAC, suggesting a protective effect of TAC against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy [57]. Serum concentrations of cardiac troponin 1 (cTn1) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were markedly reduced in the TAC group compared to the CsA group, indicating a lower incidence of cardiac toxicity associated with TAC [57].

Now that we are in the domain of therapeutic interventions, we turn our attention to the use of CsA in cancer radiotherapy [58]. Richman et al. [58] explored the potential synergy between radioimmunotherapy and CsA in the context of hormone-refractory prostate and metastatic breast cancers. Their study involved parallel phase I clinical trials, with a focus on the application of CsA to mitigate the development of human anti-mouse antibodies (HAMA) triggered by the adenocarcinoma-targeting MUC-1 antibody m170 [58]. This antibody, in combination with chelated radiometals (111In and/or 90Y), was linked by a cathepsin-degradable tetrapeptide, offering a nuanced approach to targeted therapy [58]. Remarkably, the trials, encompassing 16 patients with established bone and/or soft tissue metastases, demonstrated exemplary tumor targeting in 15 patients [58]. Both the 111 In-radioimmunoconjugate and the 90Y-radioimmunoconjugate exhibited favorable tolerability profiles [58]. Notably, a clinical dosimetry study in prostate cancer revealed a noteworthy 31% reduction in radiation dose to the liver, highlighting the efficacy of the DOTA-tetrapeptide linkage in minimizing normal tissue exposure. Despite transient myelosuppression, the trials established the viability of fractionated therapy with CsA support, offering a promising avenue for further optimization of targeted radiation therapy in solid tumors [58].

CsA was also used to treat glioblastomas. According to Shafizadeh et al. [59], CsA improved progression-free survival (PFS) in glioblastoma patients. Their study looked at the effects of short-term intravenous (IV) CsA treatment on glioblastoma [59]. Because of the crossover nature, the study was a single-centered trial with a co-primary endpoint design that focused on overall survival (OS) and PFS [59]. The study involved 118 patients, with 59 patients in each group (CsA and placebo) [59]. CsA medication began 72 hours after surgery and continued for three days [59]. Overall, the proportion of patients alive 12 months after therapy was significantly higher in the CsA group, although the exact percentage was not provided in the summary [59]. Additionally, PFS was significantly prolonged in the CsA group compared to the placebo group (6.3 ± 4.07 months vs. 3.4 ± 2.98 months, p < 0.001), but there was no difference in OS. Despite these promising findings, several limitations were noted in the study [59]. Its single-center design and short CsA administration period, along with the loss of 19 patients in the CsA group, potentially underpowered the study, making it uncertain whether the observed differences in outcomes were attributable to CsA or incomplete chemotherapy cycles [59]. Additionally, CsA administration resulted in complications such as infections and hypomagnesemia [59]. While CsA has recognized neuroprotective benefits in severe traumatic brain injury, it did not significantly enhance glioblastoma patients’ functional performance levels [59]. The observed increase in the one-year survival rate in the CsA group was considered to be influenced by patient age and the depth of surgical resection, underscoring the necessity for further research to clarify these findings [59].

Other studies have examined the use of CsA in the pharmacokinetic modulation of drugs, providing insights into the impact of CsA on drug pharmacokinetics (PK) and its potential applications in reversing drug resistance [60]: Notably, CsA’s influence on rimegepant pharmacokinetics in healthy subjects and its effects on presatovir pharmacokinetics in the context of respiratory syncytial virus infections were investigated [60].

One of the studies explored the impact of strong P-glycoprotein (P-gp) inhibitors, particularly CsA, on the PK of rimegepant in healthy subjects [60]. Co-administration with CsA led to a 60% increase in rimegepant’s area under the curve (AUC0-inf) and a 41% rise in the maximum concentration (Cmax) geometric least squares mean ratios compared to rimegepant alone [60]. These findings indicate that CsA, as a potent P-gp inhibitor, significantly elevates rimegepant exposure [60]. The heightened exposure is comparable to a rimegepant dose of 112.5 mg but remains below that of a 150 mg dose [60]. Consequently, it is recommended to limit the dosing frequency of rimegepant to no more than once every 48 hours when co-administered with CsA, to avoid excessive exposure [60]. This study underscores the critical role of P-gp inhibition by CsA in influencing rimegepant PK parameters [60].

Building on the previous study of combination therapies, Tsimberidou et al. [61] applied a gemtuzumab-based combination regimen (MFAC) for patients with previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or advanced myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). In this case, CsA as a potential multidrug resistance modifier demonstrated responses in 47% of patients with newly diagnosed AML or high-risk MDS [61]. Notably, CsA administration within the gemtuzumab regimen proved to be feasible [61]. The study suggests that CsA may modulate multidrug resistance-mediated resistance to gemtuzumab, with in vitro data supporting its potential efficacy [61]. Specifically, the MFAC regimen included gemtuzumab (6 mg/m2 intravenously on day 1), fludarabine (15 mg/m2 twice daily on days 2-6), cytarabine (0.5 g/m2 twice daily on days 2-6), and CsA (6 mg/kg loading dose followed by 16 mg/kg continuous infusion on days 1 and 2) [61]. The results showed that 46% of patients achieved complete remission (CR), with a median survival period of 8 months and a 12-month survival rate of 38% [61]. However, the regimen was associated with significant toxicities, including hyperbilirubinemia in 31% of patients and hepatic veno-occlusive disease (VOD) in 7% [61]. Infections complicated 38% of the chemotherapy courses. Despite these toxicities, CsA-associated hyperbilirubinemia was transient, and the overall incidence of gemtuzumab-associated VOD was manageable [61]. The study concluded that while the MFAC regimen holds promise, measures to avoid and/or treat VOD should be integrated into future protocols to enhance patient outcomes [61]. The overall percentage of partial recovery or complete remission was 34%, which was a promising finding [61]. Particularly, after a CR of less than a year, patients who had MFAC as the initial salvage showed an impressive 60% (3/5) complete remission rate [61]. The regimen, however, showed no complete remissions (0/7) in the most refractory patient group (initial CR duration of <1 year with one or more prior salvage treatments) [61].

Additionally, the application of CsA in reversing platinum resistance in advanced ovarian cancer was explored [62]. This study demonstrated that CsA effectively induced partial reversal of carboplatin (CBDCA) resistance in A2780 cells in a concentration- and time-dependent manner 62. A phase II trial further reported that platinum-resistant ovarian cancer patients achieved a partial response to the combination of CsA and CBDCA, showing a modest in vivo reversal of CBDCA resistance [62]. Pharmacokinetic data suggested that CsA-mediated resistance reversal occurs independently of alterations in CBDCA pharmacokinetics [62].

In the context of innovative treatment options for advanced breast cancer, the investigation of oral docetaxel and oral CsA has emerged as a compelling avenue, as demonstrated by the findings of this phase II study [63]. The primary focus of the study was to evaluate the antitumor activity of this novel combination administered twice weekly in patients previously treated with anthracycline-containing chemotherapy [63].

The pivotal metric of this exploration was the overall response rate (ORR), which stood at an impressive 51.7% [63]. A more detailed analysis of 23 evaluable patients revealed an even higher ORR of 65.2%, accompanied by a noteworthy 82.6% demonstrating meaningful disease stabilization for over 12 weeks [63]. These figures paint a promising picture, positioning the oral paclitaxel and CsA combination within the upper echelons of chemotherapy outcomes for advanced breast cancer patients. Survival metrics further underscore the efficacy of this regimen, with overall survival of 16 months and a median time to progression of 6.5 months for all evaluable patients [63]. These results not only signify a substantial advancement in the treatment landscape but also present a viable alternative for patients who may have exhausted other therapeutic options [63].

Continuing our exploration of CsA’s diverse applications, Campistol et al. [64] conducted a study comparing sirolimus (SRL) with CsA in renal transplant recipients. This phase specifically evaluated their impact on skin and nonskin cancers, spanning a five-year duration and involving patients from Australia, Europe, and Canada, with Europe contributing 82.5% of randomly assigned patients [64]. The study distinguished between skin malignancies such as Bowen’s disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ), basal cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and melanoma, taking into consideration risk factors [64]. Overall CsA withdrawal (SRL-ST) exhibited a significant reduction in the relative risk for skin cancers (p < 0.001 for both on-therapy and ITT analyses), with fewer lesions and lower mean annualized rates compared to continuous CsA-based therapy [64]. The median time to the first skin malignancy was notably delayed in SRL-ST patients [64]. Independent analysis of BCC and SCC demonstrated a favorable impact of SRL-based, calcineurin inhibitor (CNI)-free immunosuppression on mean annualized rates and a pronounced delay in the median time to the first occurrence of BCC [64].

For non-skin cancers, SRL-based therapy after CsA withdrawal significantly differed from the continuous CsA-based regimen in the ITT analysis (8.4% SRL-CsA-ST versus 3.7% SRL-ST, χ2 p = 0.043; Kaplan-Meier estimates 9.6% SRL-CsA-ST versus 4.0% SRL-ST, log-rank p = 0.032), indicating a potential reduction in nonskin cancer risk with SRL-based, CNI-free therapy [65]. Importantly, over 50% of SRL-ST patients completed the five-year therapy, underscoring the feasibility and potential efficacy of this approach in reducing cancer incidence after renal transplantation [65].

A phase II trial investigated the pharmacokinetic modulation of irinotecan in CRC patients by CsA. This trial aimed to mitigate the significant gastrointestinal toxicity commonly associated with irinotecan by inhibiting the biliary excretion of SN-38, its active metabolite, using CsA. The study involved 16 patients with 5-fluorouracil refractory CRC, where CsA (5 mg/kg) was administered as a six-hour infusion, and irinotecan (60 mg/m2) was infused over 90 minutes starting three hours after CsA initiation, repeated weekly for four weeks with a two-week rest period. The results indicated a reduction in severe diarrhea, with only 13% of patients experiencing grade 3/4 diarrhea, suggesting a notable decrease in gastrointestinal toxicity compared to the standard irinotecan regimen, which typically results in higher rates of severe diarrhea. Although clinical activity remained modest with one partial response and five cases of stable disease lasting a median of 12 weeks, the trial’s early termination due to slow patient accrual limited its statistical power. Importantly, the pharmacokinetic data suggested that CsA-mediated resistance reversal occurred independently of alterations in irinotecan pharmacokinetics, indicating a potential improvement in the therapeutic index of irinotecan without compromising its efficacy[66].

Lastly, a phase Ib trial evaluated the combination of selu-metinib and CsA in patients with advanced solid tumors, including an expansion cohort specifically for meta-static colorectal cancer (mCRC) [67]. This trial provided valuable insights [67], demonstrating a notable clinical benefit rate of 67% in the overall population, with 56% in the dose expansion cohort for mCRC patients [67]. This combination therapy showed a median PFS of 3.15 months, which, although limited as an early-phase trial endpoint, suggests potential efficacy [67]. Importantly, the investigation did not reveal significant differences in response between KRAS-mutant and KRAS wild-type patients, indicating that this treatment may be broadly applicable across different genomic profiles of mCRC [67]. These findings underscore the necessity for ongoing research to further validate the preclinical observations of Wnt pathway suppression and to refine the therapeutic strategies for enhancing treatment outcomes in mCRC [67]. The study’s comprehensive approach to safety, pharmacokinetics, and molecular response paves the way for more personalized and effective therapies, addressing the critical need for improved survival and reduced toxicity in these patients [67].

Conclusions

The ongoing exploration of CsA’s impact on cancer progression is complex, reflecting the intricate dynamics of immunosuppression and malignancy. In individuals with compromised immune systems, such as organ transplant recipients on immunosuppressive regimens, the heightened risk of cancer invasion adds a layer of complexity to the elusive role of CsA in either promoting or inhibiting cancer.

Studies conducted in both in vitro and in vivo settings have generated diverse outcomes, with murine models suggesting potential suppression of cancer growth and overcoming drug resistance under CsA treatment included in novel nanoformulations.

Although the anti-tumor effects of CsA have been explored and confirmed in various cancers, there is still an unmet need to explore them in common cancers (e.g., breast, lung, colon, and brain tumors), given their molecular complexity and heterogeneity. More specifically, the anti-tumor effects of CsA (alone and combined) should be explored in specific and more aggressive subtypes with limited targeted therapeutic options and complex microenvironments. Some of these cancers may have various intratumoral immune cells, whose interactions with CsA (or its combinations with other drugs) remain to be elucidated. In addition, the translation of these findings into clinical scenarios has yielded limited success or, in the case of nanomedicines, remains to be elucidated.

Despite the promising potential observed in in vitro studies, the clinical application of CsA in oncology necessitates meticulous consideration of its toxicity profile, especially at higher concentrations. Additionally, if utilized, the toxic effects of a nanoformulation should also be considered, as these can exert biological and toxicological actions of their own [35, 36, 68, 69]. Murine models have substantiated concerns of neurotoxicity and organ disorganization at elevated doses, underscoring the critical importance of dosage management in clinical settings.

While the potential of CsA in inhibiting tumor growth is evident, its integration into clinical practice faces challenges. CsA’s role in cancer progression appears to be influenced by various factors, encompassing treatment duration, patient populations, and specific cancer types. The discernible gap between preclinical and clinical findings underscores the urgent need for further research to reveal the true nature of CsA’s impact on cancer. This, in turn, would pave the way for more informed and targeted therapeutic approaches.

Clearly, further efforts are required to reintroduce CsA as a treatment option for various cancer types and to explore its untapped potential in the realm of cancer therapeutics.