Introduction

Gliomas, particularly glioblastomas, represent some of the most aggressive and treatment-resistant tumours within the central nervous system. The high mortality associated with gliomas necessitates a deeper understanding of their underlying mechanisms, particularly those that govern cellular survival and death [1]. Recent research has highlighted ferroptosis, a form of regulated cell death characterised by the accumulation of lipid peroxides, as a critical process influencing tumour growth and response to therapy [2]. Ferroptosis is distinct from other forms of cell death, such as apoptosis and necrosis, and is closely linked to cellular iron metabolism and reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation [3]. MUC1, a transmembrane glycoprotein, has garnered attention for its dual role in cancer biology. Traditionally recognised for its involvement in tumour progression and metastasis, MUC1 has also been implicated in the regulation of cellular stress responses, including those associated with ferroptosis [4]. Emerging evidence suggests that MUC1 may act as a negative regulator of ferroptosis, thereby contributing to the survival of glioma cells under oxidative stress conditions [5, 6]. In this study, we investigate the interplay between MUC1 and ferroptosis in glioma cells, focusing on how the expression of MUC1 is regulated by ALKBH5, an RNA demethylase known for its role in the post-transcriptional modification of RNA molecules. Recent studies have indicated that ALKBH5 can modulate the levels of various mRNAs through demethylation, influencing gene expression and cellular responses to stress [7, 8]. Our hypothesis posits that ALKBH5 negatively regulates MUC1 expression, thereby impacting the ferroptotic sensitivity of glioma cells. Through a series of experiments, we seek to elucidate the mechanisms by which MUC1 influences ferroptosis in glioma and to clarify the regulatory role of ALKBH5 in this context. We will assess the expression levels of MUC1 in glioma cells with altered ALKBH5 activity, evaluate the impact of MUC1 on ferroptosis induction, and explore the potential therapeutic implications of targeting both MUC1 and ALKBH5 in glioma treatment [9, 10]. Ferroptosis is characterised by the accumulation of lipid peroxides, primarily driven by iron-dependent oxidative stress. MUC1 can influence lipid metabolism by modulating antioxidant defences, such as glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), a critical enzyme that prevents lipid peroxidation and ferroptotic cell death. If MUC1 upregulates GPX4 expression or activity, it could directly inhibit ferroptosis. Ferroptosis is heavily dependent on intracellular iron levels, as free iron catalyses the production of ROS through Fenton reactions. MUC1 has been implicated in iron metabolism, potentially by regulating the expression of iron transporters such as transferrin receptor and ferritin. If MUC1 reduces intracellular iron availability, it could suppress ferroptotic processes in glioma cells. MUC1 is known to be involved in cellular stress responses, including oxidative stress regulation. By activating pathways such as the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 antioxidant response, MUC1 may reduce ROS accumulation, thereby lowering lipid peroxidation and preventing ferroptosis. Our research specifically explores the regulation of MUC1 by ALKBH5, an RNA demethylase that modulates gene expression through m6A demethylation. If ALKBH5 downregulates MUC1, it could potentially increase ferroptotic sensitivity in glioma cells. This suggests an indirect but functionally relevant pathway linking MUC1 expression to ferroptosis.

This study aims to provide new insights into the complex interplay between ferroptosis and tumour biology in gliomas, positing that modulation of MUC1 and ALKBH5 may offer promising avenues for therapeutic intervention in this challenging disease. By understanding these molecular interactions, we hope to contribute to the development of more effective treatment strategies for glioma patients, ultimately improving clinical outcomes.

Material and methods

Animal model and drug administration

The mice (12–16 weeks old) used for the experiment were housed in typical laboratory enclosures with four to five mice in each enclosure. They were exposed to a 12 hours light/dark cycle (lights on at 08:00) at a temperature of 21–25°C and humidity at 45–55%. Food and water were provided ad libitum, and the experiments were carried out following the regulations set by the Chinese Council on Animal Care. Attempts were made to reduce the pain experienced by the animals and decrease the number of animals used. Experiments adhered strictly to the regulations set forth by the Animal Ethics Committee of Hebei Medical University. Both sexes were used in the cisplatin (dichlorodiammineplatinum(II)) (DDP) experiments in a sex-balanced manner, and sex differences were examined using χ2 analyses. ALKBH5 knockout mice (ALKBH5–/–) and ALKBH5-knock-in mice (ALKBH5+/+) and their wild type controls were provided by Gem Pharmatech (Nanjing, China) and generated using a conventional homologous recombination gene-targeting strategy [5]. Successful knock-in was validated by sequencing genomic DNA from the knock-in mouse. At least 10 generations of backcrossing were performed to obtain animals with a C57/BL6 background. To induce AKI, 20 mg/kg body weight DDP dissolved in 0.9% NaCl solution (P4394, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was administered intraperitoneally, following a previously described protocol. The ALKBH5 inhibitors DDO-2728 (20 mg/kg) and IOX1 (20 mg/kg) (Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX, USA) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and administered to mice by intraperitoneal injection for 3 consecutive weeks before DDP administration.

ALKBH5 knockdown

Transfection: U251 cells were transfected with shRNA plasmids targeting ALKBH5 (sh-ALKBH5 #1 and #2) using a transfection reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Control cells were transfected with a non- targeting shRNA.

Overexpression

ALKBH5 overexpression

Evaluation of proliferation

Assessment of invasion

Transwell chamber assay

The invasive capability of U251 cells was evaluated using a Transwell chamber assay. Cells were plated in the upper chamber, and a medium with FBS was added to the lower chamber. After 24 hours, non-invading cells were removed, and invading cells were fixed, stained, and counted.

MUC1 overexpression

Co-transfection

To investigate the role of MUC1, U251 cells were co-transfected with sh-ALKBH5 and a plasmid encoding pcDNA3.1-MUC1. Control groups included cells transfected solely with empty vector plasmid.

Confirmation of transfection

After 48 hours of transfection, cells were harvested, and total protein was extracted. Western blot analysis was performed to assess the expression levels of MUC1 and ALKBH5 using specific antibodies. The protein levels were quantified using appropriate software for densitometric analysis.

Assessment of colony formation and invasion in U251 cells

Assessment of colony formation

Plate clone formation assay

To evaluate the ability of U251 cells to form colonies, cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 500 cells per well. After 10–14 days of incubation, colonies were fixed with 4% formaldehyde, stained with crystal violet, and counted. The number of colonies in each group was compared to assess the effects of MUC1 overexpression on the colony-forming ability of cells with ALKBH5 knockdown.

Assessment of invasion

Transwell chamber assay

The invasive potential of U251 cells was assessed using a Transwell chamber assay. Cells were plated in the upper chamber, and the lower chamber was filled with a medium containing 10% FBS as a chemoattractant. After 24 hours, non-invading cells were removed, and invading cells were fixed, stained with crystal violet, and counted. The number of invading cells in each condition was compared to evaluate the effects of MUC1 overexpression on invasion in the context of ALKBH5 knockdown.

In vivo tumour growth analysis and Ki-67 proliferation assessment

Inoculation into mice

Preparation of cells

After 48 hours of transfection, U251 cells (both sh-ALKBH5 and control) were harvested, washed with PBS, and resuspended in serum-free DMEM.

Tumour measurement

Immunohistochemical analysis

Tissue preparation

Tumour tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 5 µm slices.

Ki-67 staining

Immunohistochemical staining for Ki-67 was performed to evaluate cell proliferation. Sections were deparaffinised, rehydrated, and subjected to antigen retrieval. After blocking nonspecific binding, sections were incubated with a primary antibody against Ki-67, followed by incubation with an appropriate secondary antibody. The sections were then developed using a 3,3'-diaminobenzidine substrate and counterstained with haematoxylin.

Immunofluorescence staining

Tissue preparation

Tumour samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 5 µm slices.

Staining procedure

Sections were deparaffinised and rehydrated. Following antigen retrieval, sections were blocked with serum to prevent nonspecific binding. The sections were then incubated with a primary antibody against MUC1, followed by a fluorescently labelled secondary antibody. Nuclei were stained using DAPI.

Western blot analysis

Antibody incubation

The membrane was blocked with 5% BSA and probed with a primary antibody against MUC1, followed by an appropriate secondary antibody. The protein bands were detected using an ECL substrate.

Results

The impact of ALKBH5 knockdown on U251 cell proliferation and invasion

In this study, the result illustrates that knockdown of ALKBH5 markedly inhibits U251 cell proliferation and invasion. Panel A confirms successful transfection with sh-ALKBH5 #1 and #2 via Western blot analysis, showing reduced ALKBH5 protein levels. The CCK-8 assay (Panel B) indicates a significant decrease in cell viability in knockdown groups compared to controls (**p < 0.01). The EdU staining assay (Panel C) further demonstrates a reduction in proliferation, corroborated by the plate clone formation assay (Panel D), which shows diminished colony formation. Additionally, the Transwell chamber assay (Panel E) reveals a substantial decrease in invasion capability, reinforcing the inhibitory effect of ALKBH5 knockdown (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Knockdown of ALKBH5 inhibits U251 cell proliferation and invasion. Western blot verification of transfection efficiency after U251 cells were transfected with sh-ALKBH5 #1 or sh-ALKBH5 #2 plasmids (A), cell viability was assessed by the CCK-8 assay (B), cell proliferation ability was detected by the EdU staining assay, scar bar: 200 μm (C), cell clone formation ability was determined by the plate clone formation assay (D), cell invasion ability was measured by the Transwell chamber assay, scar bar: 200 μm (E)

Compared with the control group, **p < 0.01

Effects of ALKBH5 overexpression on U251 cell viability and invasion

The result presents the effects of ALKBH5 overexpression on U251 cells. Successful transfection with the pcDNA3.1-ALKBH5 plasmid is confirmed in Panel A. The CCK-8 assay (Panel B) shows enhanced cell viability in the overexpression group compared to controls (**p < 0.01). Proliferation, assessed by EdU staining (Panel C), and colony formation ability (Panel D) are significantly increased. The Transwell invasion assay (Panel E) confirms that overexpression of ALKBH5 promotes invasive characteristics in U251 cells (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2

. Overexpression promotes proliferation and invasion of U251 cells. U251 cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1-ALKBH5 plasmid or empty vector plasmid. Western blot was used to detect the expression level of ALKBH5 protein in the cells (A), cell viability was assessed by the CCK-8 assay (B), cell proliferation ability was detected by the EdU staining assay, scale bar: 200 μm (C), cell clone formation ability was determined by the plate clone formation assay (D), cell invasion ability was measured by the Transwell chamber assay, scale bar: 200 μm (E)

Compared with the control group, **p < 0.01

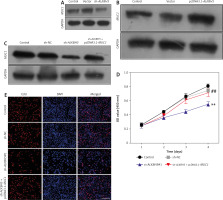

Role of MUC1 in modulating the effects of ALKBH5 knockdown on U251 cells

We investigate the role of MUC1 in modulating the effects of ALKBH5 knockdown. Western blot analysis (Panels A and B) reveals that MUC1 levels are inversely related to ALKBH5 expression. Co-transfection of U251 cells with sh-ALKBH5 and pcDNA3.1-MUC1 (Panel C) shows that MUC1 overexpression significantly rescues cell viability and proliferation, as demonstrated by CCK-8 and EdU assays (Panels D and E), compared to the sh-ALKBH5 group (**p < 0.01, ##p < 0.01) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

Overexpression of MUC1 protein reverses the inhibitory effect of ALKBH5 knockdown on U251 cell proliferation. U251 cells were transfected with sh-ALKBH5 plasmid or sh-NC plasmid. Western blot was used to detect the expression level of MUC1 protein in U251 cells (A), U251 cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1-ALKBH5 plasmid or empty vector plasmid. Western blot was used to detect the expression level of MUC1 protein in U251 cells (B), U251 cells were transfected with sh-ALKBH5 plasmid or co-transfected with sh-ALKBH5 plasmid and pcDNA3.1-MUC1. Western blot was used to detect the expression level of MUC1 protein in U251 cells (C), cell viability was assessed by the CCK-8 assay (D), cell proliferation ability was detected by the EdU staining assay, scale bar: 200 μm (E)

Compared with the control group, **p < 0.01, Compared with the sh-ALKBH5 group, ##p < 0.01

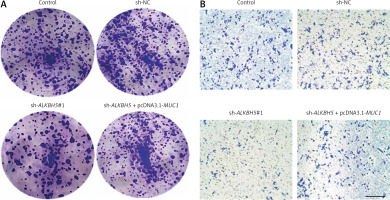

Interaction between MUC1 overexpression and ALKBH5 knockdown in U251 cells

The result further supports the interaction between MUC1 and ALKBH5. The plate clone formation assay (Panel A) indicates that MUC1 overexpression reverses the colony formation deficits caused by ALKBH5 knockdown. The Transwell assay (Panel B) similarly shows restored invasive capabilities in the co-transfected cells. Both assays demonstrate significant differences compared to control and sh-ALKBH5 groups (**p < 0.01, ##p < 0.01) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4

Overexpression of MUC1 protein reverses the inhibitory effect of ALKBH5 knockdown on U251 cells colony formation and invasion. U251 cells were transfected with sh-ALKBH5 plasmid or co-transfected with sh-ALKBH5 plasmid and pcDNA3.1-MUC1. Cell clone formation ability was determined by the plate clone formation assay (A), cell invasion ability was measured by the Transwell chamber assay, scale bar: 200 μm (B)

Compared with the control group, **p < 0.01, Compared with the sh-ALKBH5 group, ##p < 0.01

In vivo effects of ALKBH5 knockdown on tumour growth in U251 cell models

The study extends the findings to an in vivo model, where the knockdown of ALKBH5 in U251 cells leads to reduced tumour growth in mice over 21 days (Panel A). The tumour growth curve (Panel B) and tumour weight measurements (Panel C) demonstrate significantly inhibited tumour development in the ALKBH5 knockdown group (**p < 0.01). Immunohistochemical analysis of Ki-67 expression (Panel D) reveals a marked reduction in proliferation within tumour tissues, supported by the percentage of Ki-67 positive staining (Panel E) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5

Knockdown of ALKBH5 inhibits the growth of U251 cells in vivo. U251 cells were inoculated into mice, and tumour tissues were shown after 21 days (A), tumour growth curve (B), tumour weight in each group (C), immunohistochemical analysis of Ki-67 expression levels in tumour tissues, scale bar: 200 μm (D), percentage of Ki-67 positive staining (E)

Compared with the control group, **p < 0.01

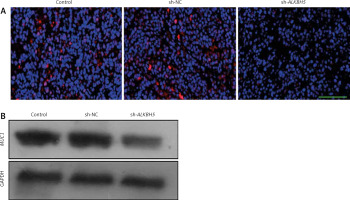

Impact of ALKBH5 knockdown on MUC1 expression in tumour tissues

The result highlights the impact of ALKBH5 knockdown on MUC1 expression in tumour tissues. Immunofluorescence staining (Panel A) and Western blot analysis (Panel B) show a substantial decreases in MUC1 levels in tumours from the ALKBH5 knockdown group compared to controls (**p < 0.01) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6

Knockdown of ALKBH5 decreases the expression of MUC1 in tumour tissue. Immunofluorescence staining was used to determine MUC1 levels in tumour tissues of each group. Scale bar: 200 μm (A), Western blot analysis of MUC1 protein expression levels in tumour tissues (B)

Compared with the control group, **p < 0.01

Discussion

This study investigated the role of ALKBH5 in U251 glioblastoma cells, focusing on its impact on cell proliferation, invasion, and interaction with MUC1. The results demonstrate that the knockdown of ALKBH5 significantly inhibits both proliferation and invasion of U251 cells, with consistent validation across various assays, including CCK-8, EdU staining, and Transwell invasion assays. Conversely, overexpression of ALKBH5 enhances these cellular characteristics, indicating its potential role as an oncogene in glioblastoma [11, 12].

The knockdown experiments reveal a clear connection between reduced ALKBH5 expression and decreased cell viability and proliferation. The Western blot analysis confirms effective transfection, while the CCK-8 assay shows a significant reduction in cell viability (p < 0.01). These findings are further supported by EdU staining and colony formation assays, which demonstrate reduced proliferation and cloning efficiency, respectively. The Transwell assays reinforce these results by showing diminished invasive capacity in the knockdown groups, underscoring ALKBH5’s role in promoting aggressive tumour behaviours [13, 14].

In contrast to the knockdown results, overexpression of ALKBH5 leads to enhanced cell viability and invasion. The ability of U251 cells to proliferate and form colonies increases when ALKBH5 is overexpressed, as shown by the CCK-8 and EdU staining assays. These results highlight the dual role of ALKBH5 as a facilitator of malignant properties in glioblastoma cells, suggesting that it could serve as a therapeutic target [15, 16].

The investigation into MUC1’s role reveals an intriguing interplay between ALKBH5 and MUC1 expression. Notably, MUC1 levels inversely correlate with ALKBH5 expression, suggesting that downregulation of ALKBH5 leads to reduced MUC1 levels. Co-transfection studies demonstrate that MUC1 overexpression can rescue cell viability and proliferation in ALKBH5 knockdown cells, indicating that MUC1 may act as a compensatory mechanism that mitigates the effects of ALKBH5 loss. This relationship is crucial because it suggests that targeting both ALKBH5 and MUC1 may yield synergistic effects in the treatment of glioblastoma [17, 18].

To extend in vitro findings to a physiological context, in vivo experiments using mice reveal that ALKBH5 knockdown significantly inhibits tumour growth over a 21-day period. The tumour growth curve and weight measurements corroborate these results, while immunohistochemical analysis of Ki-67 reveals reduced proliferation within the tumours, aligning with the in vitro observations. This not only validates the role of ALKBH5 as a promoter of tumour growth but also emphasises the importance of in vivo models in understanding tumour biology [15, 19].

The study also highlights a substantial decrease in MUC1 expression in tumour tissues following ALKBH5 knockdown, as shown through immunofluorescence and Western blot analyses. This finding further reinforces the notion that ALKBH5 plays a regulatory role in MUC1 expression within the tumour microenvironment, potentially influencing tumour behaviour and response to therapies [20, 21].

The findings from this study elucidate the critical roles of ALKBH5 and MUC1 in U251 glioblastoma cell dynamics. ALKBH5 appears to function as an oncogene promoting proliferation and invasion, while MUC1 serves as a modulator of these effects. The interplay between ALKBH5 and MUC1 may offer new avenues for therapeutic intervention, highlighting the potential for targeting these pathways in the treatment of glioblastoma. Future research should focus on elucidating the mechanisms behind this interaction and exploring the therapeutic implications of modulating ALKBH5 and MUC1 expressions in glioblastoma treatment strategies [22–24].

Limitations

The study relies on U251 glioblastoma cells, which may not fully represent the heterogeneity of glioblastomas. Additional cell lines or patient-derived glioblastoma models would strengthen the findings. While the study demonstrates a correlation between ALKBH5 and MUC1 expression, it does not fully elucidate the molecular mechanisms through which ALKBH5 regulates MUC1 or its downstream effects on glioblastoma proliferation and invasion. The in vivo component of the study is restricted to tumour volume and Ki-67 expression without further exploration of other tumour microenvironment factors, immune response interactions, or long-term survival outcomes. The study uses shRNA to knock down ALKBH5, but it does not confirm the specificity of the knockdown or address potential off-target effects, which could impact the interpretation of results. Given the emerging role of ALKBH5 in ferroptosis regulation, the study could be expanded to investigate whether ALKBH5 affects ferroptotic sensitivity in glioblastoma cells, particularly in relation to MUC1 expression.

Future perspectives

This study demonstrates a link between ALKBH5 and MUC1, and further research should investigate the precise molecular pathways involved. This includes exploring whether ALKBH5 influences MUC1 expression through m6A RNA methylation-dependent mechanisms, and identifying downstream signalling cascades affecting glioblastoma proliferation and invasion. Given the emerging role of ALKBH5 in ferroptosis regulation, future work should explore whether ALKBH5 modulates ferroptotic sensitivity in glioblastoma cells via MUC1 or other pathways. Examining metabolic alterations associated with ALKBH5 activity could provide deeper insights into glioblastoma survival mechanisms. This study suggests that ALKBH5 and MUC1 could be potential therapeutic targets. Future research should explore pharmacological inhibitors or genetic approaches targeting ALKBH5 and MUC1, alone or in combination with existing glioblastoma therapies, such as temozolomide and radiotherapy. Because glioblastoma progression is influenced by interactions with the tumour microenvironment, future studies should investigate how ALKBH5 knockdown affects immune cell infiltration, angiogenesis, and glioblastoma-associated fibroblasts. Exploring ALKBH5 and MUC1 expression in patient-derived glioblastoma samples could determine their prognostic value and potential as biomarkers for glioblastoma progression and treatment response. Future in vivo studies should include longer observation periods to assess tumour recurrence, survival outcomes, and potential resistance mechanisms that may arise following ALKBH5 modulation.

Conclusions

This study provides compelling evidence that ALKBH5 plays a critical role in the proliferation and invasion of U251 glioblastoma cells. The systematic examination of ALKBH5 knockdown and overexpression revealed that reduced ALKBH5 levels significantly inhibit cell viability, proliferation, and invasion, while its overexpression promotes these aggressive characteristics. These findings suggest that ALKBH5 functions as an oncogenic factor in the context of glioblastoma. The interaction between ALKBH5 and MUC1 is particularly noteworthy. The inverse relationship between ALKBH5 and MUC1 expression indicates that MUC1 may act as a compensatory mechanism in response to ALKBH5 knockdown. Co-transfection experiments demonstrated that MUC1 overexpression can effectively reverse the inhibitory effects of ALKBH5 knockdown on cell viability and proliferation, highlighting the potential for combinatorial therapeutic strategies targeting both proteins. The in vivo studies further substantiate the in vitro findings, showing that the knockdown of ALKBH5 results in reduced tumour growth and proliferation in a murine model. This underlines the translational relevance of the study and emphasises the potential for targeting ALKBH5 in clinical settings.

Highlights

The study reveals that ALKBH5 plays a crucial role in the proliferation and invasion of U251 glioblastoma cells, indicating its potential as a therapeutic target.

ALKBH5 knockdown via shRNA significantly reduced cell viability and proliferation, as shown by CCK-8, EdU staining, and colony formation assays.

The invasive potential of U251 cells was markedly decreased following ALKBH5 knockdown, as demonstrated through Transwell chamber assays.

In vivo studies in mice confirmed that ALKBH5 knockdown led to reduced tumour growth, lower tumour volume and weight, as well as decreased Ki-67 expression in tumour tissues.

The research highlights a significant relationship between ALKBH5 and MUC1, where MUC1 overexpression can counteract the proliferation and invasion inhibition caused by ALKBH5 knockdown, underscoring the interplay between these 2 factors.

Significance statement

This study highlights the pivotal role of ALKBH5 in regulating the proliferation and invasion of U251 glioblastoma cells, offering new insights into its potential as a therapeutic target in glioblastoma treatment by demonstrating that ALKBH5 knockdown leads to reduced cell viability and MUC1 expression, along with diminished tumour growth in vivo. The research underscores the importance of ALKBH5 in glioblastoma pathophysiology. Furthermore, the findings that MUC1 can counteract the inhibitory effects of ALKBH5 knockdown suggest a complex interplay between these factors, paving the way for future investigations into targeted therapies that could improve treatment outcomes for glioblastoma patients.