Introduction

Atherosclerosis and related cardiovascular diseases are among the most common human diseases worldwide [1]. This degenerative process of the blood vessel wall may develop and coexist in almost all vascular beds; therefore, atherosclerosis is referred to as a systemic disease. Development of atherosclerosis is closely related to the aging process of the human body. Vascular aging is a term specific for blood vessels, describing changes in the properties of the vascular wall, specifically mechanical and structural. It is characterized by the loss of arterial wall elasticity and arterial wall thickening which results in luminal dilation and reduction of arterial compliance [2, 3]. The most important early marker of arterial wall damage is endothelial dysfunction, which leads to intima-media thickening and is associated with many pathophysiological mechanisms [3]. Current studies prove that proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) takes part in many processes in the human body and its role in vascular aging could be vital.

Aim

This review highlights the impact of PCSK9 on factors responsible for vascular aging, including atherosclerosis, hyperglycaemia and pathological inflammatory response. Authors also shortly describe how PCSK9 can control human cholesterol homeostasis on molecular level.

Material and methods

A selected sampling of the publications on PubMed was conducted and a review created according to selected keywords.

Results and discussion

The characteristics of PCSK9 and its various roles in human

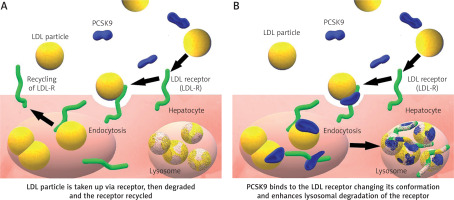

PCSK9 was identified in 2003 by Seidah et al. [4]. In humans, the PCSK9 gene is located on chromosome 1p32.3 and is expressed mainly in the liver, but also in the intestine, the kidney and even in the nervous system [5]. Basing on a meta-analysis study collecting over 300.000 patients, focused on nine most studied single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the PCSK9 gene. The rs11591147 SNP has the greatest LDL cholesterol lowering potential and thus results in the threefold CV risk reduction [6]. PCSK9 regulates LDL-C concentrations by acting on the LDL receptors (LDLR) (Figure 1) [7] but its role in human is not limited only to cholesterol metabolism. In the nervous system, PCSK9 is involved in the differentiation of cortical neurons and might have a pro-apoptotic and protective function [8]. Its concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid in humans is at 60 times lower than in human serum [9]. According to the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study, some rare polymorphisms of the PCSK9 gene are responsible for regulation of blood pressure in Afro-Americans [10]. In 2008, Feingold et al. (2008) described how inflammation stimulates PCSK9 expression, causing increased LDLR degradation, consequently increasing serum LDL level [11]. The data also show that PCSK9 has an antiviral effect against HCV virus not only by degradation of the LDLR but also downregulation of CD81 on the surface of hepatic cells – a primary HCV receptor [12, 13]. Upregulation of PCSK9 can be observed in sepsis and might impair the host immune response and survival by exacerbation of organ dysfunction and general inflammation. On the other hand, low levels of PCSK9 in septic patients seem to have a protective effect [14]. In patients suffering from stable coronary artery disease, PCSK9 levels correlate with white blood cell count [15].

Factors related to PCSK9 responsible for aging of the arterial wall

Inflammation causes endothelial dysfunction, promotes atherosclerotic plaque formation, its vulnerability and rupture [3]. There is a mechanism involving PCSK9 stimulating lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 (LOX-1). It is a major oxidized LDL receptor located in endothelial cells, associated with endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis [16]. LOX-1 expression is upregulated in inflammation [17]. Thus, inflammatory state-related atherosclerosis may be aggravated by PCSK9 stimulation of LOX-1 transcription and LOX-1 stimulation of PCSK9 expression [18]. It remains to be discovered whether PCSK9 inhibitors can prevent this process by antagonizing LOX-1 expression.Interestingly, patients suffering from autoimmune diseases demonstrate increased CV risk and subclinical atherosclerosis-related problems. These diseases are associated with a chronic inflammatory process. The most common include systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), antiphospholipid syndrome (AS), and systemic sclerosis (SS) [19]. For instance, patients suffering from SLE have significantly higher risk of premature atherosclerosis and increased CV risk [20]. According to Mok et al. (2011), there is a constant mortality pattern mostly due to CV events in SLE patients. In their study, the observed loss of life expectancy years in female patients was 19.7 years and 27 years in male patients [21]. Magder et al. (2012) conducted a cohort study on 1874 patients suffering from SLE, observing them for the period from April 1987 to June 2010. The results revealed that SLE patients have a 2.7-fold increase in risk of acute CV events (i.e. “stroke, myocardial infarction, angina, coronary intervention, and peripheral vascular disease”) relative to the expected Framingham risk score [22]. Interestingly, in SLE peripheral artery occlusive disease (PAOD) the risk is 9-fold higher relative to the general population [23]. One of the reasons for premature atherosclerosis and vascular wall aging in SLE patients is that the integrity of the arterial endothelium is damaged, either directly by binding antibodies or by deposition of autoimmune complexes [24]. The PCSK9 gene was also investigated in carriers of antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLA). Similarly to other autoimmune diseases, aPLA cause endothelial damage, and in this case, thrombosis. Comparing the aPLA carriers to a healthy control group, a relevant allelic association with the rs562556 SNP in PCSK9 was found, making the carriers more prone to thrombosis due to endothelial dysfunction [25]. There is evidence that some of the metabolic pathways of cholesterol and glycaemic control are crossed. For example, in a study conducted on 18 healthy subjects, co-regulation between the PCSK9 gene and cholesterol synthesis was tested. During a 48-hour fasting period the levels of PCSK9 in observed subjects’ plasma decreased by ∼58%, reaching the lowest point at 36 hours of fasting [26]. Moreover, a regulatory pathway of PCSK9 was recently found, which might be related to diabetes mellitus (DM). It is associated with a mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) protein complex which can be influenced by hyperglycaemia. Stimulation of mTORC1 by insulin leads to activation of protein kinase C-delta (PKCδ). As a result, the activity of HNF4α and HNF1α is inhibited, and subsequently also PCSK9 transcription [27]. Furthermore, the mTORC1 complex can be influenced by pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF) [28]. It is suggested that PKCδ plays a role in fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. Additionally, it is one of the factors responsible for liver lipogenesis regulation [29, 30]. Hyperglycaemia and conditions related to insulin resistance stimulate collagen deposition and increase lipid infiltration and smooth muscle cell proliferation and consequently alter vasomotor tone [3]. Interestingly, a recent Mendelian randomisation study proved that PCSK9 variants lowering LDL cholesterol can increase the risk of type 2 DM. The studied patients presented high circulating fasting glucose concentration, high body weight and also increased waist-to-hip ratio [31]. To summarize, PCSK9 takes part in many systemic pathologies in which vascular wall destruction and atherosclerosis aggravation are observed.

Local effect of PCSK9 on vascular wall senescence and atherosclerotic plaque

There are some age-related pathologic mechanisms including a decrease in nitric oxide bioavailability, low-grade inflammation, increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and endothelial senescence, which make the arterial wall more prone to oxidative stress [32]. With age, endothelin production is increased and smooth muscle growth promoted. Diseases such as DM or arterial hypertension (AH) increase the cardiovascular risk and boost the process of vascular aging [3]. Apart from systemic action PCSK9 can influence the vascular wall and atherosclerotic plaque locally. Giunzioni et al. (2007) described how PCSK9 mediates the inflammatory process in atherosclerotic plaque. They observed increased infiltration of inflammatory monocytes to the plaque, which differentiates to macrophages afterward (a 32% increase in inflammatory positive cells compared to the control tissue) [33]. The local PCSK9 is produced by endothelial cells, smooth muscle vascular cells and even macrophages in an atherosclerotic lesion [34]. There is a possibility that PCSK9 secreted by intraplaque macrophages can influence the monocytes to infiltrate the atherosclerotic lesion independently of its action in serum or the arterial wall [34]. The influence of local PCSK9 on foam cell receptors in the plaque is still unknown. Clinically important is the fact that composition of the plaque plays a more important role than its size regarding risk of rupture and thrombogenicity [34]. Another study described the role of PCSK9 in maturation of oxidized LDL-induced dendritic cell and T cell activation in atherosclerotic plaque. This proved the direct effect of PCSK9 on atherosclerotic plaque independently of its action on systemic LDL [35]. One of the conducted studies investigated mice kept on a cholesterol-rich diet causing hypercholesterolemia. Its aim was to evaluate the effect of anti-PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies on the atherosclerotic lesion. Not only a reduction in monocyte recruitment as the inflammatory response was observed, but also improved lesion morphology [36]. All this suggests that PCSK9 strongly influences some of the critical components of the atherosclerotic lesion formation process. This may suggest an extra beneficial effect of anti-PCSK9 therapy directly on the atherosclerotic plaque, apart from an LDL-lowering effect. Another process responsible for vascular aging is related to the reactive oxygen species (ROS). They can modulate cellular signalling pathways, inducing changes in the cellular phenotype. This particular ROS function is responsible for vascular remodelling processes. It includes modulating cellular cytoskeletal properties, cell proliferation, migration, and death and altering the extracellular matrix (ECM). All these properties of the vascular wall are linked to its mechanical characteristics and change during the vascular senescence process [37]. In a study conducted by Ding et al., low shear stress via ROS enhanced PCSK9 expression. Both vascular endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells were investigated. It was found that ROS regulated PCSK9 expression. The PCSK9-ROS interaction may be important in vascular aging and atherosclerosis propagation [38]. Within the atherosclerotic plaque, PCSK9 is present and released by smooth muscle cells (SMCs). The inflammatory cytokines released from macrophages induce the proliferation and migration of media SMCs. This causes thickening of the vessel wall and is considered to be one of the age-related impairments, a part of the vascular aging process [39]. In 2018 evidence for a direct pro-inflammatory effect of PCSK9 on macrophages was provided, mainly LDLR dependent [40]. Furthermore, silencing of PCSK9 gene expression results in suppression of macrophages’ inflammatory response to oxidized LDL, which demonstrates PCSK9’s still not fully understood role in inflammation [41].

Conclusions

Based on experimental data available to date, it can be concluded that PCSK9 is involved in many biochemical pathways associated with the vascular aging process. Progression of this process is influenced by hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, oxidative stress, inflammation, and hyperglycaemia. Diseases mentioned in this review are established factors associated with high PCSK9 serum levels, which partially explains why intensified atherosclerosis can be observed in affected patients. Keeping in mind the complex role of PCSK9, especially in lipid and glucose metabolism, inflammation and its association with atherosclerotic plaque composition, it can be expected that there will be new clinical indications for an anti-PCSK9 therapy apart from lowering serum LDL-C. Treatments using PCSK9 inhibition may not only contribute to cardiovascular risk reduction, but also alter the composition of atherosclerotic plaque and slow down the process of vascular aging.