Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common types of cancer. Specifically, it is the third most common type of cancer worldwide and the second most common cause of death due to cancer [1]. Despite such high incidence and mortality, there is a decrease in these statistics due to cancer prevention and earlier diagnosis through screening and better therapeutic options [2].

At the time of CRC diagnosis, up to 23% of patients present with metastatic CRC (mCRC). Furthermore, an estimated 25–50% of patients initially diagnosed with lymph node-positive CRC are likely to develop metastases over time. Outcomes for patients with localized CRC are significantly better than those for patients with mCRC. Notably, the 5-year survival rate is 15.6% for mCRC, compared to a much higher rate for localized CRC [3, 4].

After surgery for CRC, several important parameters should be included in the pathology report. Firstly, the stage of the disease must be clarified, and it is essential to determine whether the margins are negative or not. If the disease is at stage III, adjuvant chemotherapy is required following surgery [2]. For stage II CRC, it is necessary to note the presence of high-risk characteristics to determine whether adjuvant chemotherapy is warranted. Specifically, these characteristics include T4 tumors, inadequate lymph node sampling (< 12 nodes), poorly differentiated histology, lymphovascular or perineural invasion, bowel obstruction, localized perforation, or close, indeterminate, or positive margins and microsatellite instability (MSI). These factors assist the clinician in deciding whether to proceed with adjuvant chemotherapy [2, 5]. In some patients, colon cancer is diagnosed at the metastatic stage. Since mCRC is a heterogenous disease, it is important to clarify its molecular profile in order to decide which therapy is the most appropriate [2].

Colorectal cancer, both localized and metastatic, is molecularly diverse, and molecular profiling is crucial at every stage of its progression. Moreover, the molecular profile of CRC may change throughout the lines of treatment; therefore, performing a liquid biopsy may be useful. For instance, Zarkavelis et al.’s study explored how a subset of patients no longer displayed hotspot gene mutations after chemotherapy, indicating their potential eligibility for anti-EGFR targeted therapy and concluding that personalized therapy is crucial [6]. In addition, Żok et al.’s study highlights the heterogeneity of CRC and the negative prognostic impact of the BRAF mutation, which reduces overall survival (OS) by 2- to 3-fold. This may necessitate more intensive first-line therapy [7]. As a result, both studies emphasize the complex molecular profile of CRC and the need for a deeper understanding of it [6, 7].

Approximately 85% of CRCs arise from chromosomal instability, characterized by alterations in chromosome number and structure. Key pathways driving this instability include the Wnt and MAPK pathways. In Wnt-driven CRCs, β-catenin accumulates, activating transcription and promoting uncontrolled cell growth. In MAPK-driven CRCs, activation of receptor tyrosine kinases leads to constitutive signaling by molecules such as RAS and RAF, driving proliferation [8–10]. The remaining 15% of CRCs result from MSI, caused by mutations in mismatch repair (MMR) genes or hypermethylation of the MLH1 promoter. Tumors are classified as microsatellite stable (MSS) if no MMR mutations or MLH1 hypermethylation are present, or as microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) if at least two MMR genes are mutated [8, 10, 11].

Immunotherapy has become a promising treatment option for mCRC, especially in patients with MSI-H or dMMR tumors. It is important to note that MMR/MSI-H is present in approximately 40% of BRAF V600-mutated CRC, contributing to a more complex molecular profile [7]. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) such as pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and ipilimumab have shown effectiveness in this group by activating the body’s immune system to recognize and eliminate cancer cells [8, 10, 12].

POLE mutations, linked to DNA-repair deficiencies and high tumor mutational burden, are associated with hypermutated colorectal cancers enriched in neoantigens. These tumors are more common in younger male patients, often with right-sided primaries, and are present in less than 1% of cases [13]. Somatic POLE mutations are linked to MSS/pMMR tumors, while germline POLE mutations correlate with MSI-H/dMMR tumors. Emerging data suggest that tumors with POLE mutations may respond well to immunotherapy [14, 15].

Pembrolizumab, approved for first-line treatment of MSI-H/dMMR mCRC, showed superior outcomes in the KEYNOTE-177 trial, with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 16.5 months compared to 8.2 months for chemotherapy. The CheckMate 8HW trial also confirmed the superiority of immunotherapy over chemotherapy for dMMR/MSI-H stage IV colon cancer [16]. Other ICIs such as nivolumab and dostarlimab are also recommended for dMMR/MSI-H mCRC, with nivolumab showing promising efficacy as monotherapy or combined with ipilimumab. The CheckMate 142 trial reported a median PFS of 14.3 months and a 12-month OS rate of 73% for nivolumab [12, 17].

Although CRC therapy has evolved, there is a need for a deeper understanding of tumor evolution to develop more effective treatments. Nowadays, the scientific community is focusing on the tumor microenvironment (TME) to gain a better understanding of tumor progression. It appears that the TME plays an important role in the evolution of cancer cells through immunomodulation [18]. The tumor microenvironment is a complex milieu consisting of diverse cell types and secreted factors that play a crucial role in cancer progression. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are a major component of this environment. Tumor-associated macrophages contribute to cancer progression through various mechanisms, such as promoting tumor angiogenesis, facilitating metastasis, and suppressing the adaptive immune response [18, 19].

A phase II clinical trial (NCT05382442) evaluated the addition of ivonescimab, with or without ligufalimab, to chemotherapy in patients with metastatic or recurrent CRC. Ivonescimab is a tetrameric bispecific antibody targeting PD-1 and VEGF, while ligufalimab is a novel humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody targeting CD47. The results of the trial were very promising, demonstrating potential as a first-line therapy for these patients. This combination may significantly alter the therapeutic landscape for CRC [20].

In previous studies, we reviewed the existing literature on the role of TAMs and the correlation between the infiltration of these cells and the expression of PD-L1 in both cancer cells and macrophages in gastric and esophageal cancer [18]. In this study, we performed a review of the literature on the role of TAMs and the PD-1/PD-L1 network in CRC. We systematically reviewed the literature from three different databases (PubMed, Scopus, Cochrane) to identify available studies on the role of TAMs and the PD-1/PD-L1 network in the progression of CRC. Although the relevant literature is limited, more studies are needed to better understand these important relationships.

Review of the literature

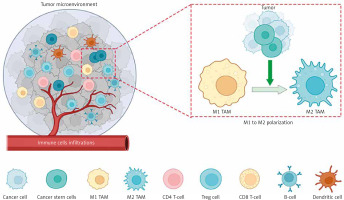

Tumor microenvironment plays a pivotal role in the progression of cancer cells in different types of cancer. This is due to the abundance and variety of cells that exist within it. Tumor-associated macrophages are the most abundant population in the TME, and there is increasing interest in their role [18]. Tumor-associated macrophages exhibit high plasticity, which allows them to be polarized into different types depending on the disease stage, affected tissue, and host microbiota. The M1 and M2 phenotypes represent the extremes of this spectrum. The M1 phenotype is pro-inflammatory and helps eliminate cancer cells, while the M2 phenotype is anti-inflammatory and supports cancer cell survival. The polarization of M1-like macrophages is marked by the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), C-X-C motif ligand 9 (CXCL9), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and C-X-C motif ligand 10 (CXCL10), which promote inflammation and exacerbate tissue damage. M2-like TAMs secrete cytokines such as arginase-1 (Arg1), interleukin-10 (IL-10), and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), forming paracrine and autocrine signaling loops. Arg1-positive macrophages are more prevalent in tumors, with autophagy playing a role in regulating Arg1 secretion. IL-10 directly suppresses T-cell function, while TGF-β1 promotes immunosuppression, cancer cell proliferation, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and cancer stem cell generation. Metabolically, M1 macrophages predominantly rely on aerobic glycolysis, similar to the Warburg effect observed in tumor cells, whereas M2 macrophages primarily utilize oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) as their main metabolic pathway [21].

Tumor-associated macrophages s express various markers, with CD164 and CD208 being specific to the M2 type, while both M1 and M2 types express the marker CD68 [19, 22, 23]. Tumor-associated macrophages, often exhibiting the M2 phenotype, are reported to influence nearly every step of tumor metastasis, including invasion, vascularization, intravasation, extravasation, establishment of pre-metastatic niches, and survival of circulating tumor cells [24]. Figure 1 shows the different cells in the TME and the polarization of TAMs.

Fig. 1

The tumor microenvironment (TME) encompasses heterogeneous cancer cells, various immune cells (such as T- and B-lymphocytes, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), dendritic cells, natural killer cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils), stromal cells (including cancer-asso ciated fibroblasts, pericytes, and mesenchymal stromal cells), as well as blood and lymphatic vascular systems. Additionally, tissue-specific cells, such as neurons and adipocytes, contribute to the TME. These cells collectively generate extracellular matrix components, growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular vesicles, enabling intricate communication within the TME

Image source: Nicolini A, Ferrari P. Involvement of tumor immune microenviron ment metabolic reprogramming in colorectal cancer progression, immune escape, and response to immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2024; 15: 1353787.

In addition, TAMs contribute to tumor progression by producing arginase, chitinase family proteins, macrophage galectin, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). They also promote cytokine secretion from vascular endothelial cells. While IL-10 expression is upregulated in TAMs, the expression of immunosuppressive factors such as TGF-β, IL-12, MHC molecules, and reactive nitrogen intermediates is downregulated. M2 TAMs facilitate tumor progression through multiple pathways, making it a complex process [24–26].

While normal macrophages exert cytotoxic effects by synthesizing nitric oxide (NO) through the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) pathway using L-arginine as a substrate, this pathway is suppressed in M2 macrophages. Instead, M2 macrophages metabolize L-arginine into ornithine and polyamines, which promote tumor cell proliferation. Furthermore, TAMs secrete various cytokines, including epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), platelet-derived growth factor, and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), contributing to cancer progression by expanding the affected tumor area [26, 27].

Moreover, TAMs degrade the extracellular matrix (ECM) through enzymes such as MMPs and cathepsins, facilitating cancer cell detachment and metastasis. Co-culture models reveal that TAMs activate NF-kB and JNK pathways, enhancing cancer cell invasiveness. Additionally, TAMs accelerate epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via TNF-α and Snail upregulation, further promoting metastasis and recurrence [26, 27].

Angiogenesis, a critical process in solid tumor progression, is influenced by various regulatory factors, including TAMs. The density of TAMs is positively associated with microvessel density and VEGF levels in tumors, making them independent prognostic indicators of survival. Macrophage depletion using clodronate liposomes significantly reduces angiogenesis, highlighting their key role. Tumor-associated macrophages secrete pro-angiogenic factors such as IL-8, CCL8, bFGF, and VEGF, which promote vascular formation. Additionally, TAMs stimulate Ang expression in colon cancer cells through IL-1 and TNF-α secretion, further promoting vascularization. Tumor-associated macrophages accumulate in hypoxic, ischemic, and necrotic tumor regions due to chemoattractants such as EMAP II, endothelin-2, and VEGF. Under hypoxia, TAMs upregulate numerous pro-angiogenic molecules, including VEGF, MMPs, CXCL8, and IL-6, amplifying angiogenesis.

Moreover, the presence of M2 TAMs in tumor tissues significantly contributes to the immunosuppressive TME. In the early stages of tumor progression, classically activated macrophages produce NO, which induces widespread tumor cell death. However, as tumors advance, cancer cell-derived PGE2 and IL-10 impair M1-mediated immune responses. M2 TAMs neither express tumor-associated antigens in vitro nor enhance the anti-cancer activity of T-cells and natural killer (NK) cells, directly limiting the host’s anti-tumor immunity. Tumor-derived cytokines, including IL-4 and TGF-β, inhibit macrophage IL-12 secretion, suppressing NK and cytotoxic T-cell proliferation. Necrotic tumor cells release immunosuppressive factors, such as IL-10 and S1P, driving macrophage polarization to the M2 phenotype. This transition reduces NO and iNOS production, while MMPs cleave Fas ligand on cancer cells, rendering them resistant to both chemotherapeutic agents and immune cell-mediated lysis. These TAM-induced immune regulatory changes play a critical role in immunosuppression [26, 27].

Extracellular vesicles (EVs), acting as information carriers between cells, are secreted by all cell types. Recent studies have shifted focus from cancer cell-derived EVs to those produced by TAMs. Tumor-associated macrophages-derived EVs play a dual role in antitumor therapy. MicroRNAs (miRNAs), key regulators of gene expression encapsulated in EVs, significantly impact macrophage polarization. Tumor-associated macrophages-derived EVs containing miR-146a facilitate the repolarization of M2 macrophages to the M1 phenotype, while miR-19a-3p and miR-155 are linked to M1 polarization. However, TAM-derived EVs also contribute to the immunosuppressive microenvironment. For instance, miR-29a-3p and miR-21-5p suppress STAT3 in CD4+ T-cells, causing a Treg/Th17 imbalance in epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) and promoting cancer progression. Similarly, miR-223 transferred by TAM-derived EVs enhances EOC progression, while miR-21-5p and miR-155-5p promote metastasis in CRC cells [26, 27].

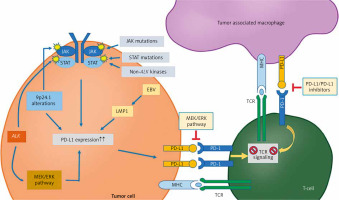

Tumor-associated macrophages are thought to be regulated by two types of signals: “eat me” signals, which activate TAM functions, and “do not eat me” signals, which inhibit them. The PD-1/PD-L1 axis is part of the latter category. Tumor-associated macrophages can express PD-1 on their surface and bind to PD-L1, which is expressed on cancer cells. M2 TAMs tend to overexpress the PD-1 ligand, forming an axis with the PD-L1 ligand on cancer cells. This interaction promotes an immunosuppressive environment, aiding cancer progression and potentially facilitating immune evasion. Figure 2 illustrates the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway in both TAMs and T-cells. However, many questions remain about the exact relationship between TAMs and the expression of the PD-1/PD-L1 axis [28, 29].

Fig. 2

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway in tumor cells, tumor-associated macrophages, and T-cells within the tumor microenvironment

Image source: PD-1/PD-L1 pathway: a therapeutic target in CD30+ large cell lymphomas ALK – anaplastic lymphoma kinase – a receptor tyrosine kinase involved in cell growth; rearrangements are implicated in several cancers, EBV – Epstein-Barr Virus – a herpesvirus associated with several malignancies, including nasopharyngeal carcinoma and some lymphomas, LMP1 – latent membrane protein 1 – an EBV-encoded protein with oncogenic properties, MEK/ERK – mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase – part of a signaling pathway that regulates cell division and survival, MHC – major histocompatibility complex – a set of genes encoding cell-surface proteins essential for immune recognition, TCR – T-cell receptor – a molecule on T-cells that recognizes antigens presented by MHC molecules Image source: Xie W, Medeiros LJ, Li S, et al. PD-1/PD-L1 pathway: a therapeutic target in CD30+ large cell lymphomas. Biomedicines 2022; 10: 1587.

Tumor-associated macrophages function is regulated by two types of signals: “eat me” signals, which activate macrophage phagocytosis, and “do not eat me” signals, such as PD-1, which inhibit phagocytosis. PD-1, a 55-kDa transmembrane protein from the B7-CD28 superfamily, interacts with two ligands – via PD-L1 and PD-L2. The extracellular domain of PD-1 binds to these ligands, while its cytoplasmic tail contains an immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory motif (ITIM) with two tyrosine residues. Upon engagement with PD-L1, the PD-1/PD-L1 axis is activated, resulting in phosphorylation of the tyrosine residues in the ITIM domain. This phosphorylation triggers the recruitment and activation of SHP1 and SHP2 proteins, which lead to dephosphorylation of myosin IIA and ultimately prevent cytoskeletal rearrangement, thereby inhibiting macrophage activation [28].

Tumor-associated macrophages infiltration and colorectal cancer prognosis

The role of TAMs in the progression of CRC is controversial, and different studies have obtained different results. In Edin et al.’s study, the role of TAMs in CRC was evaluated through an in vitro cell culture system of macrophage differentiation. The study concluded that TAMs play a positive role in CRC, unlike in other types of cancer, where this infiltration negatively impacts prognosis. Specifically, tumor-secreted factors alone seem to generate a mixed TAM phenotype, sharing features of both M1 and M2 macrophages, but resembling M2 more closely. This phenotype may be the cause of the more positive role of TAMs in prognosis of CRC patients [30]. In addition, other studies have also shown such a positive impact of infiltration of TAMs [31, 32].

Nevertheless, other studies conclude that TAMs have a negative impact in the prognosis of those patients [33–35]. Specifically, Inagaki et al.’s study showed an increase in pan-macrophage and M2 macrophage counts, as well as the M2/M1 ratio, at the invasive front with tumor progression. Additionally, it was observed that the number of M1 macrophages was lower, and the number of M2 macrophages and M2/M1 ratio were higher in the lymph node metastasis-positive group compared to the metastasis-negative group. This suggests that TAMs at the invasive front play a critical role in CRC progression. It is believed that monocytes are recruited to the tumor and polarize into M1 or M2 macrophages in response to tumor- and stromal cell-secreted chemokines and cytokines in the TME. These dynamic changes likely promote monocyte recruitment and polarization into M2 macrophages at the invasive front, facilitating tumor progression [24]. Additionally, Yang’s meta-analysis concluded that a high density of pan-TAMs in the invasive margin is linked to a positive prognosis in CRC patients, whereas a high density of M2 macrophage infiltration in the tumor core is a strong indicator of poor prognosis [36].

Infiltration of tumor-associated macrophages and expression of PD-L1

It seems that there is a connection between the infiltration of TAMs and the expression of PD-1/PD-L1 in CRC. However, the available data on this correlation are scarce, and more studies need to be conducted to explore this further. Parcesepe et al.’s study concluded that the expression of immune antigens and the progression of cancer in CRC are interconnected. Specifically, it showed that the expression of both PD-L1 and TAMs, which in the study are referred to as CD68+ and CD163+ cells, contribute to an ‘immune resistance’ environment [37].

In Cantero-Cid et al.’s study, the role of CD14+ cells, which are macrophages, was examined. It was specifically noted that CD14+ cells in tumor tissue displayed an M2-like alternative phenotype, characterized by elevated expression of CD64 and CD163. These cells also showed higher levels of PD-L1 compared to non-cancerous cells. The infiltrating CD14+ cells with high PD-L1 expression interacted with CD3+PD-1+ T-cells, potentially triggering “T-cell exhaustion,” a phenomenon that impairs the T-cell response to tumor growth [38]. In addition, Cheruku’s study concluded that PD-1-positive macrophages exhibit a profile consistent with M2-TAMs and demonstrate reduced phagocytic activity compared to PD-1-negative macrophages in non-cancerous tissues [39]. Table 1 summarizes the role of TAMs in CRC, highlighting their prognostic significance and PD-L1 expression.

Table 1

Summary of studies investigating the role of tumor-associated macrophages s in colorectal cancer

| TAM infiltration and CRC prognosis | ||

|---|---|---|

| Edin [30] | TAMs play a positive role in CRC | |

| Forssell [31] | TAMs play a positive role in CRC | |

| Zhou [32] | TAMs play a positive role in CRC | |

| Yang [33] | TAMs play a negative role in CRC | |

| Kang [34] | TAMs play a negative role in CRC | |

| Pernot [35] | TAMs play a negative role in CRC | |

| Infiltration of TAMs and expression of PD-L1 | ||

| Parcesepe [37] | Expression of PD-L1 and TAMs contribute to an ‘immune resistance’ environment | |

| Cantero-Cid [38] | CD14+ cells in tumors display an M2-like phenotype with high PD-L1 expression, potentially inducing T-cell exhaustion and impairing anti-tumor immunity | |

| Cheruku [39] | PD-1+ macrophages show an M2-TAM-like profile with lower phagocytic activity than PD-1- macrophages in non-cancerous tissues | |

However, the role of TAMs in the resistance of immunotherapy is not only due to the expression of PD-L1. This procedure is more complex. Generally, the anti-inflammatory TME establishes immunosuppressive networks that lead to immune resistance, ultimately promoting tumor growth and metastasis. Key factors contributing to tumor immune suppression include high extracellular matrix density, hypoxia, immunosuppressive cytokines, toxic metabolites and elevated expression of immune checkpoint molecules. Additionally, various types of TME, characterized by different compositions and proportions of immune cells, are closely associated with the effectiveness of immunotherapy [40].

Discussion

Colorectal cancer remains one of the leading causes of cancer-related morbidity and mortality worldwide. Despite advancements in early detection, improved screening methods, and the development of more effective therapeutic options, CRC continues to present significant clinical challenges, particularly in metastatic stages. Patients with mCRC face a notably poor prognosis, highlighting the urgent need for more effective treatment strategies [2, 41].

The evolving landscape of CRC treatment underscores the importance of understanding the disease’s molecular heterogeneity. The identification of molecular markers such as MSI-H or dMMR has allowed for the use of ICIs such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab as first-line treatments for patients with advanced or mCRC, resulting in improved PFS and OS rates. Although immunotherapy represents a promising therapeutic approach, particularly for patients with MSI-H or dMMR tumors, more research about the TME is important [42, 43].

Tumor microenvironment is a complex network of cells and extracellular components that interact to influence tumor progression and immune evasion. Tumor-associated macrophages are a critical component of the TME, and their role in CRC progression is gaining attention. Tumor-associated macrophages exhibit considerable plasticity and can polarize into pro-inflammatory M1 or anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes. The predominance of the M2 phenotype in the TME is generally associated with tumor progression, immunosuppression, and poor prognosis. M2 macrophages are known to facilitate tumor metastasis, promote angiogenesis, and suppress adaptive immune responses, all of which contribute to the aggressive behavior of CRC [31].

The relationship between TAM infiltration and CRC prognosis is complex and has been a subject of ongoing debate. Some studies have suggested a positive prognostic role for TAMs, with increased infiltration correlating with better outcomes, possibly due to their dual M1/M2 polarization or their involvement in tissue repair mechanisms. In contrast, other studies have shown that a high density of M2 TAMs in CRC is associated with worse outcomes, particularly in patients with metastatic disease. This discrepancy may be due to differences in study design, patient populations, or the methods used to assess TAM infiltration. It is clear, however, that TAMs at the invasive front of the tumor, especially those exhibiting the M2 phenotype, play a significant role in promoting CRC progression and metastasis [30–36].

The interaction between TAMs and immune checkpoint molecules, particularly the PD-1/PD-L1 axis, represents another key area of interest in CRC. Tumor-associated macrophages have been shown to express PD-1, and their interaction with PD-L1 on tumor cells can contribute to immune evasion and tumor progression. The presence of PD-L1 on both tumor cells and infiltrating TAMs creates an immunosuppressive environment that promotes tumor survival and immune resistance. Studies have suggested that high levels of PD-L1 expression in TAMs may be associated with T-cell exhaustion, a phenomenon in which T-cells lose their ability to recognize and eliminate tumor cells effectively. This may impair the efficacy of immunotherapies targeting PD-1 or PD-L1, underscoring the need for further investigation into the mechanisms underlying TAM-PD-L1 interactions in CRC [37–39].

Despite the growing body of evidence linking TAMs, PD-1/PD-L1 expression, and CRC prognosis, the data remain inconclusive, and further studies are necessary to clarify the precise role of TAMs in CRC progression.

Although the role of TAMs is controversial, their use as biomarkers could be beneficial if successfully implemented. The total macrophage count, measured by CD68-expressing cells, is positively associated with survival in both primary tumors [44] and metastases [45, 46], whereas macrophages expressing the pro-tumor marker CD163 are linked to poor clinical outcomes [47–49]. Large-scale gene expression analyses have also shown a negative correlation between macrophage-specific signatures and CRC prognosis [50, 51]. Macrophages impair lymphocyte function in CRC, though this effect can be reversed through pharmacological interventions [52, 53]. However, translating these findings into clinical applications is challenging due to differences in surface markers and functionality between mouse and human macrophages. Recent studies have further explored the genetic variability and plasticity of the innate immune system in humans [54–57]. In CRC patients, the CCL5-CCR5 axis can be targeted to reprogram macrophages, offering therapeutic potential despite earlier rodent model data suggesting adverse effects [52, 58]. Another critical role of macrophages in CRC treatment is their involvement in antibody-dependent cytotoxicity via Fc γ receptors (FcγR). Although some studies have indicated that FcγR polymorphisms may influence CRC treatment response [59–62], these findings have not been consistently replicated, leaving their role as clinical biomarkers unclear [62]. Generally, TAMs express PD-1, and treatment with anti-PD-1 agents enhances the phagocytic activity of PD-1+ TAMs, making TAMs that express PD-1 potential biomarkers [63].

Conclusions

In conclusion, the role of TAMs and the PD-1/PD-L1 axis in CRC progression represents an exciting and rapidly evolving area of research. However, a better understanding of the molecular and immune landscape of CRC, including the precise role of TAMs, is essential for improving patient outcomes and developing more targeted, personalized therapies. Further studies, particularly those exploring the relationship between TAM infiltration, PD-L1 expression, and immunotherapy response, are needed to optimize treatment strategies and improve survival rates for patients with CRC.