Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common malignancies and the first cause of cancer death worldwide. It is currently estimated that about 20–25% of lung cancer patients survive five years since the diagnosis [1–3]. Patients suffering from disseminated non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) without actionable mutations have a poor prognosis with median overall survival (OS) of approximately 12–16 months [4]. Various attempts have been made to increase survival of these patients by multimodal treatment. Patients treated with first-line systemic treatment for the advanced NSCLC usually progress in sites affected by the disease, e.x. intrathoracic, raising a question about consolidative treatment [5–8]. At the same time some patients with limited dissemination (only a few metastatic sites) may have a long OS, especially if these metastatic sites are treated by local modalities. This intermediate state between a local and widely disseminated disease is called the oligometastatic state, as postulated by Weichselbaum and Hellman almost 30 years ago [9, 10].

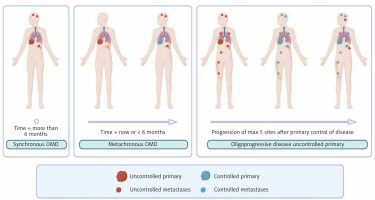

Oligometastatic disease (OMD) in NSCLC is defined as not more than 5 metastases and not more than 3 organs involved [11, 12]. Synchronous oligometastatic disease (sOMD) is OMD when metastases are observed at the moment of diagnosis or within 6 months, whereas metachronous – after 6 months. If disseminated disease is controlled by systemic treatment in all metastases except up to 5 metastases, such a state is called an oligoprogression (OPD) (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1

Graphical characteristic of oligometastatic disease

OMD – oligometastatic disease Image source: Jasper K, Stiles B, McDonald F, Palma DA. Practical management of oligometastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2022; 40: 635-641.

Categorizing these three subgroups may have a biological rationale. Synchronous oligometastases arise from primary tumours with genetic alterations that enable early spread but limit metastatic progression [13]. They often share driver mutations (e.g. epidermal growth factor receptor – EGFR) with the primary tumour, supporting a clonal origin [14]. In brain metastases they usually retain core genetic changes and acquire additional private mutations [15]. Metachronous OMD (mOMD) emerge after a tumour-free interval. If systemic therapy is used, these lesions may originate from dormant residual cells, acquiring new mutations under selective pressure from chemotherapy or targeted treatment, which is especially typical for oligoprogressive metastases [13, 14]. Several phase II clinical trials have demonstrated progression-free survival (PFS) benefit when systemic therapy was combined with local ablative therapy (LAT) [16–18].

Radiotherapy, which is a LAT assessed in this article, might be given as a part of radical treatment in sOMD or mOMD. In a patient with OPD, LAT aims to sterilize clones of progressing tumour cells before it spreads across the body, enabling continuation of the same systemic treatment acting in non-progressing areas. This study aims to provide evidence of everyday practice in a large hospital in Northern Poland.

Material and methods

We retrospectively reviewed records of the consecutive patients treated with use of stereotactic radiation therapy (SRT) at the University Clinical Centre in Gdańsk, Poland between January 2016 and December 2022. Among them, 127 patients had not more than 5 metastases and not more than 3 organs involved and were selected as oligometastatic NSCLC (sOMD, mOMD or OPD) for current analysis. Positron emission computed tomography (PET/CT) was done in 80 of 109 (73.4%) patients with sOMD and mOMD, the rest of the patients were staged by CT with contrast enhancement. None of the patients with OPD had PET/CT as for disseminated disease, CT with contrast is our local standard due to reimbursement. For some patients, who at that time underwent subsequent SRT, also previous SRT treatments were included in the analysis. Survival was calculated from the day of treatment start. The biologically equivalent dose (BED) was calculated using the formula: BED = nd (1 + d/(α/β)), where n = number of fractions, d = dose per fraction. α/β = 10 Gy was chosen for all the histology’s and sites of the tumour which is a conventional and pragmatic assumption [19, 20]. Based on literature data, neutrocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was assessed as ‘high’ for values above 3 or ‘low’ below and equal to this number [21, 22]. Continuous variables were summarized with means and ranges and ANOVA test was used for comparison (more than 2 groups). Categorical variables of patients’ baseline characteristics were presented as percentages. Between-group comparisons for categorical variables were performed using the χ2 test. Kaplan-Meier curves were plotted to calculate the survival rates. Univariable/univariable and multivariable/multivariable analyses were done using Cox proportional hazard models. Variables that passed the univariable screening (threshold p < 0.15) were entered into a backward stepwise selection algorithm based on likelihood ratio tests with a p-value threshold of 0.05 to generate a final model. Statistical significance was defined as p ≤ 0.05 throughout the study. Statistical analysis was performed with ISPSS Software (version 29.0.0.). The Medical University of Gdańsk Institutional Review Board approved the study (approval no. NKBBN/575/2021).

Results

Study population and baseline patient characteristics

Characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. In the group of 127 patients with OMD NSCLC, 44 presented with sOMD, 65 with mOMD and 18 with OPD. Majority (92.7%) of the patients with sOMD and mOMD did not have targetable mutation or their mutational status was unknown, whereas the rest of the patients (7.3%) had mutation not amenable to targeted therapy at the moment of diagnosis in 1st line (KRAS G12C, HER2, EGFR exon 20). Most of the patients with OMD NSCLC had single metastasis in one organ (75.6%). Most common locations of metastases were lungs, brain and adrenal glands: 50.4%, 37%, 8.7% of patients, respectively. Treatment was well tolerated in the majority of patients. Three patients died within 2 months since LAT – one with OPD in central nervous system (CNS), second with sOMD who underwent LAT for lung and brain and third with mOMD with LAT to the brain. Early disease progression in the brain was the reason for death in these patients.

Table 1

Patient characteristics

[i] ACC – adenocarcinoma, LCC – large-cell carcinoma, mOMD – metachronous oligometastatic disease, N/A – not applicable, NOS – not otherwise specified, NSCLC – non-small cell lung cancer, OMD – oligometastatic disease, OPD – oligoprogression, SCC – squamous-cell carcinoma, sOMD – synchronous oligometastatic disease

Median BED was 100 Gy (range 35.7–151.2 Gy). Most common doses and fractionation according to the location of metastases are shown in Table 2. Lower BED was used in intracranial vs. extracranial disease (54.2 Gy vs. 108.2Gy, p < 0.01).

Table 2

Fractionation schedule depending on location

Median PFS for sOMD and mOMD was 11.1 months (95% CI: 3.7–18.5) and 14.4 months (95% CI: 9.8–19.0), respectively (p = 0.61). Local ablative therapy enabled continuation of the same systemic treatment in the OPD group with median time to second progression of 5.3 months (95% CI: 0.3–10.3). Median OS for sOMD and mOMD was 24.5 months (95% CI: 12.5–36.6) and 36.8 months (95% CI: 27.1–46.6), respectively (p = 0.11) (Fig. 2 A, B).

Single lesions in lungs which was presumed to represent metastatic disease could be a second primary cancer, influencing patients prognosis/second primary lesion/cancer. Therefore, we also evaluated if the site of spread might be a predictor of survival. All patients with OMD (sOMD or mOMD) were divided into two groups – with oligometastases in lungs only (lungOMD) or in other sites. Median PFS in lungOMD vs. extrathoracic-OMD was 15.4 months (95% CI: 11.5–19.2) vs. 10.7 months (95% CI: 6.9–14.6, p = 0.06) and median OS was 40.9 months (95% CI: 30.7–51.2) vs. 23.6 months (95% CI: 20.1–27.1, p = 0.007), respectively (Fig. 2 C, D).

Impact of metastases in the CNS on survival in the whole OMD group was also assessed. PFS and OS in patients with vs. without CNS involvement were 11.7 months vs. 14.4 months (95% CI: 5.9–17.5 and 95% CI: 10.8–18.0, p = 0.57) and 20.0 months vs. 37.2 months (95% CI: 10.2– 29.8 and 95% CI: 28.0–46.4, p = 0.01), respectively (Figs. 2 E, F).

Neutrocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio, informing about host immunity (cut off value = 3), was used in the survival analysis. We observed no impact of NLR on PFS (median of 13.7 for low NLR vs. 15.1 for the high NLR group, p = 0.280) or OS (median of 30.9 months vs. 30.1 months, p = 0.431, respectively).

Univariable and multivariable analysis is shown in Table 3.

Table 3

Univariable and multivariable analysis

Synchronous oligometastatic disease

Treatment of the primary lesion was decided by the multidisciplinary tumour board. There was no impact of the type of primary treatment on PFS (surgery vs. radiation: 13.7 months vs. 11.1 months, p = 0.603) or OS (surgery vs. radiation: 30.9 months vs. 24.3 months, p = 0.998). For lymph node-positive tumours conventional or mildly hypofractionated radiotherapy was the most common choice (80%) followed by surgery (20%). All metastatic lesions were treated by stereotactic radiotherapy.

According to T-stage category there were 14.0% of patients with T1 tumours, 41.9% with T2, 20.9% with T3 and 23.3% with T4. Most patients had N0 stage (53.5%) followed by N1 (23.3%) and N2 (23.3%). There were no patients in N3 stage. There was no significant impact of T-stage nor N-stage category on PFS or OS.

Patients who were treated with systemic therapy and LAT had longer PFS than those treated with radiation only (median of 13.7 months vs. 7.3 months, p = 0.044). There was also a trend for OS benefit (35.0 months vs. 20.4 months, p = 0.092), which was significant in the final multivariable model (Table 3).

Apart from age (patients on systemic therapy were younger: 65.2 years vs. 72.7 years, p < 0.001) there was no difference between other variables, including Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, sex, number of metastases, number of sites affected by disease and histopathological type of the tumour between patients treated with systemic treatment + LAT vs. LAT alone in the sOMD group.

Metachronous oligometastatic disease

To assess if the interval between diagnosis of primary disease and occurrence of metastases affects outcome, patients were divided into two groups based on median time between those events (19.8 months). Median PFS favoured the group with later occurrence of oligometastases (23.0 months vs. 13.7 months, p = 0.049), however there was no significant difference for OS (median OS of 43.4 months vs. 41.3 months, respectively, p = 0.883) (Fig. 2 G, H). There was no statistical influence on survival due to histology of the tumour.

As for sOMD, there was no PFS or OS difference when patients were grouped by T and N category.

Oligoprogression

In the cohort of patients with OPD, the majority were diagnosed with adenocarcinomas. 83.3% of patients had tumours with targetable molecular alterations (ALK rearrangement 44.4%, EGFR mutation 27.8%, KRAS G12C mutation, 11.1%). 66.7% of patients were treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) and 27.8% with immunotherapy (those without actionable mutations and some with KRAS mutation). One patient was previously treated with anti-EGFR-TKI, then he was given systemic treatment with chemotherapy and he received LAT after progression on chemotherapy. This patient had very rapid progression with OS since LAT of 2.4 months. In the OPD group there was no difference in PFS no matter whether the patient was given LAT due to OPD on immunotherapy vs. TKI, 6.4 months vs. 3.0 months (p = 0.735).

Discussion

Results of this study are concordant with data reported in the literature. The Phase II SABR-COMET trial showed that addition of LAT to the systemic treatment of OMD (18 patients out of 99 had NSCLC) is associated with increase of 5-year OS (42.3% vs. 17.7%, p = 0.006) [17]. In Gomez et al. trial, patients with NSCLC whose disease had not progressed after 3 months of induction chemotherapy were randomized either to observation or LAT (surgery or radiation). Median PFS was favourable in the LAT group, 11.9 months vs. 3.9 months [18]. A similar trial by Iyengar et al. favoured the LAT arm, with median PFS of 9.7 months vs. 3.5 months (p = 0.01) [16]. Both trials were terminated earlier than expected by Data Safety Monitoring Committees, which decided that putting patients in the systemic treatment only group might not be ethical. In our group, median PFS was similar to experimental arms of those trials (13.7 months for sOMD treated with LAT + systemic treatment).

According to guidelines, patients usually should have a systemic treatment as a backbone in sOMD [23–26]. In our study, we observed a PFS benefit of adding systemic treatment on top of LAT (median of 13.7 months vs. 7.3 months), but no OS benefit. We observed that apart from other factors, younger patients received systemic treatment. This may be due to multiple factors, including different biology of the disease and comorbidities.

Although the currently accepted definition of OMD considers involvement of up to 3 organs and up to 5 metastases, in our study almost 94.5% of patients had involvement of only 1 organ and 95.3% of them have 1 or 2 metastases, reflecting the real-world decision process. Some could argue that this might lead to bias because of underrepresentation of patients with 2–3 organ involvement and 3–5 metastatic lesions, however a similar distribution was observed in other studies. In the SABR-COMET trial, 74.7% of all randomized patients had 1 or 2 lesions [17]. Another study assessing the pattern of metastatic spread in PET/CT showed that the distribution is bimodal with 26% of patients with 1, 12% with 2, 14% with 3–5, 5% with 6–9 and 43% with more than 10 metastases [27].

In mOMD, the longer the interval to its occurrence, the higher the likelihood that the metastatic lesion could represent a second primary tumour. This could influence the prognosis of the patient. To confirm this hypothesis we separated patients with mOMD by the time of occurrence of new lesions and observed that those above the median of 19.8 months had a better prognosis than those below. Whether this is due to possible higher percentage of second primary tumours or a more benign behaviour of disseminated disease, is unknown. Another tool assessing interval between occurrence of new metastases is distant metastasis velocity. Willmann et al. calculated that patients with a higher number of new metastases per month have a poorer prognosis. Patients were categorized to < 0.5, 0.5 to 1.5, and > 1.5 metastases per month and reported a median OS of 37.1, 26.7, and 16.8 months, respectively (p < 0.0001) [28].

In our study, there was no difference in PFS between sOMD and mOMD (median of 11.1 months vs. 14.4 months, p = 0.61). This may also be biased by short follow-up of some patients as they left our hospital and were controlled in other institutions. OS, which was a more relevant endpoint as we had survival data of all of the patients, was favouring mOMD vs. sOMD (36.8 months vs. 24.5 months, p = 0.11). This is in line with data from the literature, e.g. in a systematic review of patients with NSCLC who underwent adrenalectomy, median OS was longer in mOMD vs. sOMD (31 months vs. 12 months, p = 0.02) [29]. Another observation that T- and N-category did not statistically influence the survival of the patients in our research is not in line with previous findings where node involvement was a negative prognostic factor [26, 30, 31].

In the analysed group, most patients were diagnosed with adenocarcinoma. This represents the global trend of higher adenocarcinoma incidence [32]. Our data are in line with other published results from OMD NSCLC [30].

Majority of our patients in mOMD and sOMD were without targetable mutations. This is because in our department, patients with disseminated disease are routinely qualified for upfront treatment with TKIs without LAT and stereotactic radiotherapy is used for oligoprogressive lesions. Such management is because results with systemic treatment for mutation addicted NSCLC are good and a measurable lesion is needed to reimburse the systemic treatment. However, there are studies supporting combination of LAT in mutation addicted OMD NSCLC [33–35]. Xu et al. conducted a retrospective study to investigate whether LAT could improve the survival of EGFR-mutant OMD NSCLC during the first-line TKI therapy and revealed that the all-LAT group had better PFS and OS than the part-LAT or non-LAT group (median PFS 20.6, 15.6, and 13.9 months, respectively, p < 0.001; median OS 40.9, 34.1, and 30.8 months, respectively, p < 0.001) [36]. There was no survival difference between the part-LAT and non-LAT groups [36]. A recent study showed that addition of SRT 1 month after start of EGFR-TKIs in OMD could increase PFS (15.5 months vs. 9.3 months) without increase in OS and at the price of higher toxicity (G1–G2 pneumonitis 89.74% vs. 0.0%) [37]. Our results show survival in patients who usually would receive only immunochemotherapy or chemotherapy alone, underlying possible importance of adding local therapies to this group of patients with poor prognosis [23, 24].

Although median BED (α/β) was 100, common SRT doses used in brain were much below 100 and most of the extracranial metastases received more than 100 Gy. The biologically equivalent dose around 100 Gy is documented as ablative with approximately 90% of local control [19]. In our group, patients had a lower dose to brain metastases (median BED = 54.2 Gy) in comparison to locations outside the brain (median BED = 108.2 Gy) which is related with different doses and fractionations prescribed. Recommendations of treatment regimens vary depending on locations and for brain metastases, doses are usually 1 × 18–20 Gy, 3 × 9 Gy, 5 × 6–7 Gy; for lungs 1 × 30–34 Gy, 3 × 10–18 Gy, 4 × 12 Gy, 5 × 10–11 Gy, 8 × 7.5 Gy [25, 26, 38]. Doses for intracranial and extracranial metastases vary due to both radiosensitivity differences and the need to minimize normal tissue toxicity. Factors like tissue type and the presence of hypoxic conditions influence specific radiosensitivity, e.x. brain metastases can develop resistance to radiotherapy due to the expression of specific proteins like S100A9 and targeting such proteins may enhance radiosensitivity in these lesions [39]. There is much debate if metastases in OMD need such a high dose, e.g. BED of 75 Gy to adrenal gland metastases appears be sufficient [20, 40]. In the recently published OligoCare study, median BED for NSCLC metastases was 85.3 Gy [20]. Optimal doses of radiotherapy in management of oligometastatic NSCLC have not yet been established and there are ongoing trials exploring this topic [41]. The SINDAS trial demonstrated that the combination of 1st generation (gefitinib, erlotinib, or icotinib) and SRT (25–40 Gy in 5 fractions) led to a median OS of 25.5 months, compared to 17.4 months with TKI monotherapy. Whether these results are valid also for 3rd generation TKIs remains a question [42]. The NORTHSTAR trial is prospectively evaluating osimertinib with upfront local treatment vs. osimertinib alone [43].

Apart from a single fraction of 20 Gy for brain metastases, all of our radiotherapy schedules were multifractiona- ted. Results of the SAFRON II trial support efficacy and safety of SRT in 1 fraction for pulmonary metastasis [40]. This could influence further management of the patients not only because of feasibility and the impact on the radiation resources, but also with respect to facilitation of systemic treatment of OMD. According to the guidelines, LAT should be delivered in the shortest possible interval, enabling the shortest withdrawal of systemic treatment, or preferably continuation of systemic treatment during LAT [41]. This is especially important in NSCLC OPD with actionable mutations during TKI treatment as interruption of systemic therapy may lead to tumour flare [44].

Radiotherapy as LAT is safe. In the trial published by Gomez et al., G3 toxicity was 20% in the LAT arm in comparison to 8% in the control arm and there were no G4/5 toxicities [18]. Although 3 of our patients passed away within 2 months after LAT, disease progression was the cause of their death [45]. In the OligoCare trial, acute grade ≥ 3 SRT-related adverse events occurred in 0.5% of the patients, including 0.1% fatal AEs [20].

This study has several limitations: retrospective nature, different schedules of radiotherapy, and single-centre setting with possible implication of the local practice patterns.

Future trials should validate ctDNA-guided strategies and refine patient selection for curative-intent approaches basing on inflammatory status and genetic alterations [46, 47]. Also timing of LAT has to be defined [25, 26, 42].

Conclusions

Despite recent developments, the optimal patient selection for treatment of OMD remains a therapeutic challenge. Our research confirms previous data reported in the literature and adds to the existing body of evidence on OMD treatment outcomes. Patients with OMD may benefit from a combination of systemic treatment with local radiotherapy and radical treatment in this patient subset may lead to survival similar to those reported for stage III NSCLC. Patients in good performance status with one metastasis in one organ should receive a curative therapy as their prognosis is markedly better than for patients with higher metastatic burden.