Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common cancers in the world, ranking third in terms of incidence and second in terms of cancer-related mortality globally. According to GLOBOCAN 2020 there were 1.93 million new cases and 935,000 deaths due to CRC [1]. The burden of CRC varies significantly across regions of the world, with higher incidence rates observed in countries with greater levels of development, reflecting lifestyle and dietary risk factors [1]. In Poland, the current epidemiological data show 16,000 new cases of CRC and more than 12,000 deaths annually [2]. CRC accounts for 9.6% and 12.4% of the total incidence of malignant neoplasms in women and men, respectively, and is the second leading cause of death in men and the third in women [2]. The Polish Ministry of Health regulates treatment reimbursement in metastatic CRC (mCRC) with targeted therapy. In patients with mCRC, assessment of KRAS, NRAS (exclusion of mutations in exons 2, 3, and 4 of both genes), and BRAFV600E mutations is required before eligibility for treatment [3]. As of March 2023, the panel of preliminary biomarkers has been expanded to include assessment of DNA mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR) and microsatellite instability (MSI) due to the reimbursement for pembrolizumab in the first line, and nivolumab with ipilimumab from the second to fifth-line in patients with confirmed high MSI (MSI-H) or dMMR [4]. This is in line with the recommendations from the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) regarding biomarker assessment for RAS and mismatch repair/MSI status determination in mCRC patients eligible for first-line treatment [5–7].

The BRAF mutation (mainly V600E) is present in approximately 6–11% of mCRC cases and is associated with an aggressive disease course and lower responsiveness to chemotherapy [7–11]. In this group of patients, combination (doublet or triplet) chemotherapy plus bevacizumab in first-line treatment is recommended [7–12]. In 2022, Martinelli et al. [13] published the results of a re-trospective, multicenter observational study evaluating real-world first-line treatment of BRAFV600E-mutant mCRC patients – CAPSTAN CRC (NCT04317599). This study is Europe’s most significant real-world analysis, providing valuable insight into routine first-line treatment practices in these patients.

We present data on the clinical treatment patterns of BRAFV600E -mutated mCRC patients from five oncology centers in Poland who were treated between 1 June 2011 and 1 August 2023.

Material and methods

Study design

This study is a retrospective, multicenter, observational analysis conducted in Poland on BRAFV600E-mutated mCRC adult patients (aged 18 or older) treated between 2011 and 2023. This study was approved by the Bioethics Committee, Medical Chamber, Opole (Agreement No. 345/2022). All data were de-identified to ensure complete protection of personal information; therefore, patient consent was not required. All research was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Key study endpoints

The primary objective was to describe treatment patterns and durations in adult patients with BRAFV600E- mutated mCRC at five Polish oncology centers. Secondary objectives included describing the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of these patients and evaluating the effectiveness of treatment in terms of progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) compared to the results of the CAPSTAN CRC study [13].

Statistical analyses

The statistical analysis was performed using R statistical software version 4.3.1 [14]. The primary tumor staging was conducted using the seventh edition of the TNM classification developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) [15]. Follow-up was assessed from diagnosis until death or the last available follow-up information. PFS was defined as the period between the initiation of systemic palliative treatment and progression or death (from any cause), whereas OS was determined as the period between the diagnosis of disseminated disease and death (for any reason). Patients were observed until death, loss to follow-up, or the study cut-off date (August 2023), whichever occurred first.

The PFS and OS data from the CAPSTAN study were extracted from Figures 3A and 3B [13] using the IPDfromKM package [16], based on the Kaplan-Meier curve and the number at risk table. Data visualization was performed using the ggplot2 and survminer packages [17, 18].

Results

Study population

The study group included 130 Caucasian patients with mCRC, aged 18 years and older, with confirmed BRAF mutation, diagnosed and treated at one of five Polish oncology centers (Gdańsk, Opole, Warszawa, Wrocław, and Kraków) between 2011 and 2023. The BRAFV600E mutation was found in 126 patients; the remaining patients, who had rarer variants detected (D594G in two patients, K6601E in one patient, and L597R in one patient), were excluded from the treatment efficacy analysis. The population flow chart is shown in Figure 1. All patients were tested for BRAF and RAS mutations once, using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) performed on archival paraffin-embedded tumor tissue, before starting first-line treatment.

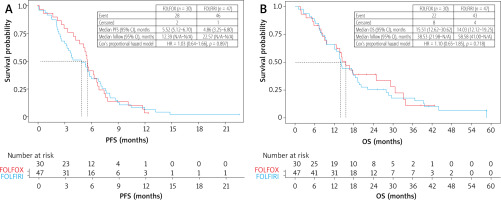

Figure 2

KaplanMeier estimates for (A) progressionfree survival (PFS) and (B) overall survival (OS) according to 1st metastatic colorectal cancer treatment FOLFIRI vs. FOLFOX

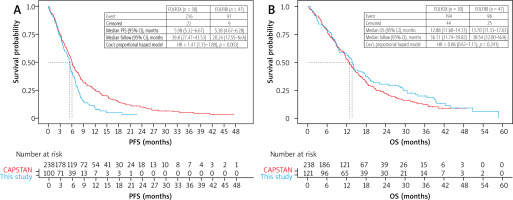

Figure 3

Nondirect comparison: this study and CAPSTAN CRC. A) progressionfree survival (PFS); patients receiving 1st line chemotherapy were included, n = 100. B) Overall survival (OS); patients with systemic disease at diagnosis were included, n = 121

The 126 patients included 69 (55%) females and 57 (45%) males. The median age for females was 68 years (45–85). The males were slightly younger; the median age was 66 years (range 42–78) (Table 1). The majority of patients, n = 71 (56%), had a right-sided primary tumor (caecum; ascending; hepatic flexure: 20 (16%), 36 (29%), 15 (12%), respectively) and n =13 (10%) transverse colon, while the remaining n = 42 (33%) had a left-sided tumor (splenic flexure; descending, sigmoid colon, rectum 2 (2%), 2 (2%), 24 (19%), 14 (11%), respectively) (Table 1). The majority of cases were tubular adenocarcinomas not otherwise specified (NOS, n = 96; 76%), with mucinous adenocarcinomas being less frequent (n = 22; 17%), followed by signet-ring cell adenocarcinomas (n = 2; 2%) and undifferentiated adenocarcinomas (n = 4; 3%). Mucinous carcinoma occurred with a similar frequency on both sides of the colon (right and left) (p = 1.00). Histopathology grades G1, G2, and G3 were found in 4 (3%), 70 (56%) and 39 (31%) patients, respectively. The clinical stage at the time of diagnosis was stage II in 13 patients (10%), stage III in 36 patients (29%), and stage IV in 77 patients (61%). Of the 49 patients with stage II or III disease, 36 received adjuvant chemotherapy. The most common adjuvant regimens were FOLFOX (folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin; n = 18) and LV/FU (folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil; n = 14). Additionally, two patients received XELOX (capecitabine plus oxaliplatin), and two received capecitabine monotherapy. All patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy relapsed. The median time from dia-gnosis to recurrence was 13.6 months (95% CI: 11.0–18.9). Liver metastases were present in 60 patients (47.6% of the total group), peritoneal metastases in 45 patients (35.7%), metastases to extra-regional lymph nodes in 45 patients (35.7%), lung metastases in 23 patients (18.3%), and metastases to other organs in 15 patients (11.9%).

Table 1

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients (N = 126)

Treatment patterns by line of therapy

The first-line palliative systemic treatment was received by 100 patients (79.4%). The remaining patients (n = 26) were excluded due to insufficient treatment data (n = 3) and lack of metastatic disease confirmation (n = 2); eight patients did not receive treatment due to poor performance status (n = 5), lack of consent to therapy (n = 2) and coronavirus disease 2019 (n = 1). For 13 patients, no data were available.

The majority of patients (85 patients, 85%) received doublet chemotherapy: FOLFOX (folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin), FOLFIRI (folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil, irinotecan), XELOX (capecitabine, oxaliplatin), and FOLFIRI and bevacizumab: 30 (30%), 47 (47%), 5 (5%), 3 (3%), respectively. Only three patients (3%) received FOLFOXIRI (folinic acid, fluorouracil, oxaliplatin, irinotecan), and one received FOLFOXIRI with bevacizumab. Monotherapy with folinic acid and fluorouracil, irinotecan, oxaliplatin, and pembrolizumab was administered to 5 (5%), 1 (1%), 1 (1%), and 1 (1%) patients, respectively. Three patients were treated in clinical trials (capecitabine, bevacizumab), but the regimen is unknown for two of them. The response to first-line treatment was assessed in 89 patients; of these, a complete response (CR) was observed in 3 patients (3.37%), a partial response (PR) in 16 patients (18.00%), stable disease (SD) in 35 patients (39.33%), and disease progression (PD) in 35 patients (39.33%). The median duration of first-line treatment for the overall population was 5.4 months (95% CI 4.7–6.3).

A comparison of the two most commonly used first-line chemotherapy regimens, FOLFOX vs. FOLFIRI, showed a slightly higher response rate for FOLFOX, but without statistical significance (2 CR, 4 PR, 13 SD, and 8 PD vs. 0 CR, 7 PR, 15 SD, and 20 PD). Furthermore, these regimens showed no differences in PFS and OS (Figures 2A, 2B).

Subsequently, 50 (40%), 20 (16%), 6 (5%), and 1 (1%) patients received second, third, fourth, and fifth-line treatments, respectively. The most commonly used second-line chemotherapy regimens were FOLFOX (n = 8; 16%), FOLFOX plus bevacizumab (n = 13; 26%), FOLFIRI (n = 13; 26%), and FOLFIRI plus aflibercept (n = 7; 14%). Other regimens included trifluridine and tipiracil (n = 2; 4%), capecitabine (n = 1; 2%), and MLF (folinic acid, fluorouracil, mitomycin C) (n = 1; 2%). The response to second-line treatment was assessed in 37 patients: 1 CR, 3 PR, 9 SD, and 25 PD. At the time of data collection, two patients were still undergoing second-line chemotherapy and were excluded from the therapy duration analysis. The median duration of second-line of treatment for the overall population was 3.0 months (95% CI: 2.5–6.2).

The most common third-line regimens were trifluridine and tipiracil (n = 7; 35%). Other regimens included FOLFOX (n = 3; 15%), FOLFOX plus bevacizumab (n = 1; 5%), FOLFIRI (n = 2; 10%), XELOX (n = 1; 5%), irinotecan (n = 1; 5%), and nivolumab (n = 1; 5%). One patient was treated in a clinical trial and received encorafenib plus cetuximab. The response to third-line chemotherapy was assessed in 15 patients: 5 SD, 10 PD, and no CR and PR. The median duration of third-line treatment for the overall population was 1.9 months (95% CI: 0.9–4.3). Fourth-line chemotherapy was administered to six patients: trifluridine and tipiracil (n = 2; 33.3%), capecitabine (n = 3; 50%), and irinotecan (n = 1; 16.3%). One patient received nivolumab and ipilimumab in a clinical trial as fifth-line treatment.

During the follow-up period, 96 (79.3%) patients died. The median follow-up time was 38.54 months (95% CI: 32.0– not reached). The median OS from mCRC diagnosis was 13.7 months (95% CI: 11.3–17.6 months). In a non-direct comparison, PFS in our study was shorter (5.38 vs. 5.98 months, HR = 1.47, p = 0.003), but OS was similar to that of CAPSTAN CRC (HR = 0.86, p = 0.24) (Figures 3A, 3B).

Discussion

According to international recommendations, the choice of first-line treatment in patients with mCRC is influenced by the presence of genetic abnormalities (RAS, BRAF, dMMR/MSI), tumor side (right vs. left colon), comorbidities, and performance status (PS) [5–7].

Despite research findings and international recommendations, treatment is often conditioned by insurance coverage or reimbursement in clinical practice in many countries. In Poland, the reimbursement provision for bevacizumab during the period covered by this analysis included first-line treatment with FOLFIRI only for patients with performance status ECOG 0–1, with KRAS or NRAS gene mutations and after a previous adjuvant regimen with oxaliplatin. Second-line treatment with FOLFOX was reimbursed for patients with PS ECOG 0–2, who had not received an adjuvant oxaliplatin-based regimen, and after prior use of irinotecan in first-line treatment [3]. The European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) recommends second-line therapy for BRAFV600E-mutated mCRC with encorafenib and cetuximab [5]. However, this therapy was not reimbursed in Poland and could only be obtained through the Emergency Access to Medicines procedure or in clinical trials.

As a result, despite the perceived lack of access to effective second-line treatments, doublet chemotherapy rather than triplet chemotherapy remains the more common second-line option in Poland.

The BRAFV600E mutation is a well-known negative prognostic factor in mCRC, associated with a 2–3-fold decrease in OS [19, 20]. The median OS in our study was 13.7 months (range 11.3–17.6), which did not differ significantly from the median OS of 12.9 months (range 11.6–14.1) in the CAPSTAN CRC study, the largest project evaluating real- world treatment practice for patients with BRAFV600E- mutated mCRC across Europe. CAPSTAN CRC included 255 patients from 34 medical centers in seven European countries (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom), where first-line treatment was initiated between January 1, 2016, and December 31, 2018 [13]. Similar to the CAPSTAN CRC study, most patients in our study received a first-line regimen with two drugs rather than three, and a few received bevacizumab due to reimbursement restrictions.

In the CAPSTAN CRC study, first-line treatment patterns differed between countries. For instance, in Belgium, Germany, and Italy, the first-line treatment was doublet chemotherapy plus anti-VEGF in 60.7%, 53.3%, and 51.9% of patients, respectively [13]. Doublet chemotherapy and doublet chemotherapy plus targeted therapy were equally common in France and Spain [13]. Furthermore, the me-dian duration of first-line treatment was similar in our study and the chemotherapy-alone subgroup in CAPSTAN CRC: 5.26 and 4.35 months, respectively. Unfortunately, data from real-world practice and our study confirm that only 50% of patients could receive potentially effective second-line therapy.

The aggressive course of mCRC with the BRAFV600E mutation argues for more intensive first-line therapy. In clinical trials, the three-drug regimen FOLFOXIRI versus FOLFIRI, also in combination with bevacizumab, was shown to increase objective response rates and PFS, albeit with a higher risks of grade 3 or 4 adverse events and only a slight improvement in OS [21–24]. Another approach with fewer side effects involves upfront administration of eight cycles of FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab, followed by maintenance therapy with 5-FU/LV plus bevacizumab, with reintroduction of the same regimen after disease progression [25].

The BRAFV600E mutation in mCRC negatively affects the efficacy of monotherapy with anti-EGFR antibodies (cetuximab and panitumumab). However, the effectiveness of combining anti-EGFR and chemotherapy in first-line treatment needs further clarification [26–30]. The phase 3 BEACON CRC study demonstrated the activity of cetuximab in combination with the BRAFV600E-mutated gene kinase inhibitor encorafenib in patients with disease progression after one or two previous regimens [31]. This regimen was associated with statistically significant increases in OS, PFS, and response rates compared with the control group: by 3.4 months (9.3 vs. 5.9), 2.8 months (4.3 vs. 1.5), and 17.7% (19.5 vs. 1.8%), respectively. This dual-targeted therapy was registered by the United States FDA (Food and Drug Administration) and EMA (European Medicines Agency) in 2020 and is recommended as a second- or third-line treatment in international guidelines [32, 33]. However, available data from clinical practice indicate that most BRAFV600E-mutated mCRC patients do not receive the recommended treatment [34, 35].

Another therapeutic target, dMMR/MSI-H, is found in approximately 40% of BRAFV600-mutated CRC. In MSI-H mCRC, first-line immunotherapy with pembrolizumab or nivolumab, and low-dose ipilimumab, has been shown to improve survival parameters [36, 37]. As mentioned above, MSI assessment, similar to RAS and RAF, is required in Poland before patients can be considered eligible for first-line therapy.

While aware of the limitations of retrospective studies, this study provides valuable insight into the findings of the European CAPSTAN CRC study. Moreover, the CAPSTAN CRC study indicated that mCRC BRAF testing is far less commonly performed in Eastern Europe compared to Northern and Western European countries [13]. We report that in Poland, BRAFV600E has been routinely assessed with PCR or next-generation sequencing (NGS) testing in parallel with RAS before first-line treatment for more than six years. Unfortunately, despite performing molecular assessments, our analysis shows that patient access to second-line molecular targeted therapies has yet to improve due to reimbursement restrictions.

According to data from the National Cancer Registry in Poland, approximately 16,000 new cases of CRC are diagnosed annually. About 25% are in the advanced stage, including an estimated 400 patients with a BRAFV600E mutation [2]. Therefore, it remains essential to establish optimal treatment strategies for this overlooked subpopulation in both first- and second-line settings.

Conclusions

As with many other cancers, mCRC is a molecularly diverse group of tumors. The treatment landscape for BRAFV600E-mutated mCRC is complex and still continues to evolve [38]. This study highlights the significant unmet need for more effective treatment strategies for patients with BRAFV600E-mutated mCRC in Poland.