Summary

The approach for anterolateral popliteal artery (PA) puncture recommends the use of sheaths or devices with a diameter of 3.0 Fr or smaller; however, inserting sheaths with a diameter of 4.0–6.0 Fr can expand the treatment options. We retrospectively reviewed cases of endovascular therapy in which a 4.0–6.0 Fr sheath was inserted via anterolateral PA puncture and found no complications such as bleeding or compartment syndrome associated with sheath insertion.

Introduction

Although the maturation of endovascular therapy (EVT) treatment strategies and the development of devices have made it possible to treat many cases using only the antegrade approach, the distal artery approach is still sometimes necessary when treating complex lesions. The distal approach includes superficial femoral artery (SFA) puncture distal to the adductor canal in the supine position [1], posterior popliteal artery (PA) puncture [2], PA puncture with the foot raised [3] and puncture of below the knee artery, etc. However, the anterolateral PA puncture technique reported by Tan et al. in 2017 is a convenient method that is easy to prepare for in terms of body position during puncture [4]. There are few original articles on the anterolateral PA puncture technique, and the puncture and hemostasis methods vary between institutions. Because the distance from the body surface to the popliteal artery is longer than that with other puncture methods, the use of devices up to 3.0 French (Fr) is recommended to avoid the risk of difficulty in hemostasis [4]. With devices up to 3.0 Fr, the only devices that can be used are limited to guidewires and microcatheters; thus, the treatment strategy is also limited. Anterolateral PA puncture is often used when an attempt at antegrade wiring to pass through to the true lumen of a peripheral artery fails in the case of an occlusive lesion in the SFA or when an attempt at antegrade wiring to penetrate the lesion is difficult in the case of a highly calcified lesion. At our institution, we use the knuckle wire technique with a 0.035-inch guidewire to treat occlusive lesions in the SFA. However, the wire may pass through the false lumen. In such cases, an anterolateral PA puncture is performed, a sheath is inserted into the PA, and the controlled antegrade and retrograde tracking (CART) technique [5] is used to dilate a 4.0–5.0 mm balloon in the peripheral artery, and an antegrade wire is re-entered to perform revascularization. For this reason, at our institution, we often use a sheath with a diameter larger than 3.0 Fr to insert the balloon, but there are no reports that support the safety of hemostasis when using a large-diameter sheath. In addition, no established methods for hemostasis have been reported.

Aim

We retrospectively investigated the outcomes and presence or absence of complications in cases in which a sheath with a diameter of 4.0 Fr or more was inserted using anterolateral PA puncture at our institution, and we also reported on the methods for hemostasis.

Material and methods

We investigated the devices used, hemostasis methods, and complications in cases in which the PA approach was performed using anterolateral PA puncture among the EVTs performed at our institution from January 2021 to March 2025. The PA approach is frequently used to treat occlusive SFA lesions.

For occlusive lesions of the SFA, we initially attempted anterograde wiring using the ELITECROSS (Cordis, Tokyo, Japan) and Radifocus Guidewire 0.035 inch, J-curve 220 cm (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) via the contralateral femoral artery approach using the knuckle wire technique. If the wire did not pass through the true lumen of the peripheral artery, a sheath was inserted into the PA via anterolateral PA puncture, and a 0.014-inch guidewire was advanced retrogradely, and then a 4.0–5.0 mm balloon was inflated in the peripheral artery. We used a 0.014-inch guidewire to perform reentry into the true lumen using the CART technique [5] and performed revascularization. In some cases, we performed the PA approach for the purpose of ablating calcification with bidirectional biopsy forceps for severe calcification or for the purpose of performing stent placement when it was difficult to approach the contralateral femoral artery.

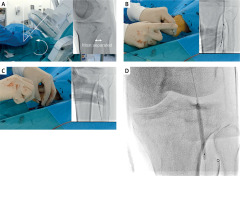

The anterolateral PA puncture was performed as follows. After setting the fluoroscopy tube at 45° of the same-side oblique position, the lower leg was adducted so that the tibia and fibula were most separated (Figure 1 A). Assuming that the PA runs along the medial edge of the fibular head [6, 7], an 18-gauge puncture needle was prepared and the PA was punctured while performing contrast angiography (Figure 1 B). After the puncture, a 0.035-inch wire was inserted (Figure 1 C), followed by inserting a sheath. After the EVT was completed, the sheath was removed after the PA was dilated with a 4.0–5.0 mm balloon for 10 min (Figure 1 D).

Figure 1

Anterolateral popliteal puncture procedure. A – The tube is set in an ipsilateral oblique position at 45°, and the leg is internally rotated so that the tibia and fibula are farthest apart. B – Assuming that the popliteal artery runs along the medial border of the fibular head, the popliteal artery is punctured with an 18-gauge needle, with contrast. C – A 0.035-inch wire is inserted after checking the backflow of blood from the outer cannula. D – The sheath is removed while ballooning the popliteal artery to achieve hemostasis

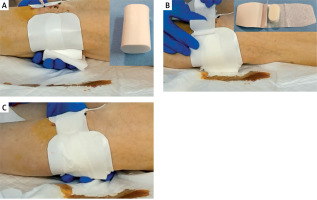

The hemostasis method was as follows. The area to be compressed is confirmed fluoroscopically in advance. The dorsal side of the PA was compressed using hemostatic compression cotton (Figure 2 A). The puncture site on the body surface was compressed with Stepty (NICHIBAN, Tokyo, Japan) (Figure 2 B) and fixed with an adhesive elastic bandage (Figure 2 C). The patient was prohibited from walking for 1 night after treatment and was allowed to walk the next morning after removal of the compression hemostatic dressing.

Figure 2

Compression hemostasis. A – After confirming the insertion site of the sheath into the popliteal artery with fluoroscopy, the dorsal popliteal artery is compressed using hemostatic compression cotton. B – The puncture site on the body surface is compressed with Stepty. C – Hemostatic compression cotton and Stepty are fixed with an adhesive elastic bandage

Results

A total of 179 EVTs were performed at our institution from January 2021 to March 2025, and 14 were performed via the PA approach using the anterolateral PA puncture. The location and shape of the treated lesion, the approach site, the device used, the sheath inserted into the PA, and the presence or absence of balloon hemostasis and complications are presented in Table I. The only complication was the formation of an arteriovenous shunt in Case 1 [8], and there were no other complications, such as hematoma formation due to bleeding, PA occlusion, or compartment syndrome. In Cases 1 to 10, compression hemostasis from inside the PA was also used in combination with balloon dilation during sheath removal, but in Cases 11 to 14, only compression hemostasis from the body surface was used without balloon hemostasis. An overview of each case is described below.

Table I

Patient backgrounds and procedure outcomes

Cases 1–7 and 10–12 underwent EVT for occlusive SFA lesions. As described in the Methods section, a knuckle wire was placed via the contralateral femoral artery approach, and if the wire did not pass through the true lumen, a PA approach was used via an anterolateral PA puncture. Introducer 4.0 Fr (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan), Halo One 5.0 Fr (Becton Dickinson, New Jersey, USA) and Glide Sheath 5.0 Fr (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) were used for retrograde insertion of a 4.0 to 5.0 mm balloon. After EVT, a 4.0–5.0 mm balloon corresponding to the diameter of the PA was used to dilate and compress the insertion site for 10 min. Case 1 was the first case of anterolateral PA puncture at our institution, and we had difficulty puncturing the PA; therefore, we created an arteriovenous shunt during the puncture and sheath insertion. When the sheath was removed, balloon hemostasis was performed for 10 min and an arteriovenous shunt was noted on subsequent lower limb arteriography (Figure 3 A). The arteriovenous shunt was almost completely eliminated by two 10-minute balloon dilations (Figure 3 B). No arteriovenous shunt was observed on the next day’s lower limb artery ultrasound, and there has been no recurrence of arteriovenous shunts in the outpatient clinic for approximately 3 years since then [8]. In Case 7, contrast media showed bleeding after 10 min of balloon dilation (Figure 3 C), but the patient was able to recover without complications by applying pressure to the surface of the body to stop the bleeding (Figure 3 D). In Case 10, the patient had an occlusive lesion in the popliteal artery, and after stent implantation, the stent was dilated for 10 min using a balloon. At that time, the Introducer 4.0 Fr sheath was removed. The insertion site of the sheath was not dilatated with a balloon, but there were no bleeding complications.

Figure 3

A case of complication and a case of bleeding at the sheath insertion site. A – An arteriovenous shunt is observed. The shunt was formed distally from the sheath insertion site and probably formed during puncture. B – Twice additional 10-minute balloon hemostasis was performed. Subsequent contrast showed that the arteriovenous shunt had almost disappeared. C – After 10 min of balloon hemostasis, the contrast shows the bleeding from the sheath insertion site to the puncture site on the body surface. D – Manual compression of the popliteal artery from the dorsal side was performed immediately, and the bleeding disappeared. Therefore, the patient was treated with compression hemostasis without additional balloon hemostasis

In Cases 8 and 9, calcified lesions in the common femoral artery and SFA were ablated using biopsy forceps via the contralateral femoral artery approach. However, the biopsy forceps were difficult to operate, so an Introducer 6.0 Fr sheath was inserted from the PA to perform retrograde ablation with the biopsy forceps. In Case 9, the Introducer 6.0 Fr was damaged because the calcified tissue grasped by the biopsy forceps was large; thus, it was replaced with a Halo One 6.0 Fr during the procedure. After 10 min of balloon compression during sheath removal, external pressure was applied to perform hemostasis, and no complications occurred. One of these 2 cases was reported in a previous case report [9].

Case 12 was an occlusive lesion in the left SFA with severe calcification. It was difficult to pass a 0.035-inch knuckle wire in the antegrade direction using the contralateral femoral artery approach, and it was also difficult to pass a 0.014-inch guidewire. We attempted to change the sheath from 4.0 Fr to 5.0 Fr to use a Crosser (Becton Dickinson, New Jersey, USA) in a retrograde approach, but the sheath change failed, and the procedure was terminated without revascularization. As the SFA was occluded and balloon hemostasis was not possible, the puncture site of the PA was compressed from the body surface to stop the bleeding. However, the next day’s plain CT of the lower limbs showed no hematoma formation, and the patient was in good condition.

Cases 13 and 14 were difficult to access due to lesions in the contralateral femoral artery; thus, a left radial artery approach was used to contrast the lower limb arteries during the PA approach. A Halo One 6.0 Fr sheath was used to deliver the stent retrogradely. As in cases 1–10, it was difficult to achieve balloon hemostasis from the contralateral femoral artery, and there was no balloon to reach the PA via the radial artery approach. Therefore, the sheath was removed without balloon hemostasis, and only surface compression was performed. There were no complications, such as hematoma formation.

Discussion

Treatment strategies for occlusive SFA lesions have matured, and the number of revascularization cases using antegrade wiring is increasing. In addition, re-entry devices such as the Outback catheter (Cordis, California, USA) have been developed for use when the wire reaches the false lumen of the peripheral artery [10]. However, there are cases in which it is difficult to perform antegrade wiring due to severe calcification, and there are also cases in which it is difficult to guide the wire into the true lumen even with a re-entry device due to the large space in the false lumen through which the wire has passed. There are also situations in which a distal approach is required, such as when there is a lesion at the approach site for catheter insertion. The options for a distal approach include SFA puncture distal to the adductor canal in the supine position, posterior PA puncture, PA puncture with the foot raised, and below-the-knee artery puncture. However, anterolateral PA puncture is often used as a simple method because the vessel diameter is large and the positioning is simple. However, because the distance from the body surface to the PA is long, there have been concerns about whether it is possible to achieve sufficient compression hemostasis, and there has been hesitancy to insert a wide-diameter sheath. The use of a wide-diameter sheath with an anterolateral PA puncture is useful because it expands the range of treatment options, such as stent placement using a distal approach or the use of an atherectomy device. For this reason, we thought that reports supporting the safety of inserting a wide-diameter sheath were significant.

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is generally performed using the radial artery approach, except in cases of complex lesions. However, in some cases, the brachial artery approach is chosen due to difficulties in palpating the radial artery, strong arterial bending, or narrow vessel diameter. After performing PCI via the radial artery approach, the sheath is removed, and compression hemostasis is performed on the body surface. However, compared with the radial artery, the frequency of complications is high, and there have been reports of thrombus occlusion, hematoma, and pseudoaneurysm [11]. The brachial artery is anatomically close to the surface of the body, so it seems easy to compress, but one of the reasons why it is difficult to achieve sufficient compression hemostasis is that the brachialis muscle is located on the dorsal side of the artery, so it is difficult to apply pressure to the dorsal side. When comparing the upper and lower limb arteries, the PA corresponds to the brachial artery. Anterolateral PA puncture involves puncturing the skin and passing between the tibia and fibula to puncture the PA. Therefore, it is easier to apply pressure to achieve hemostasis from the back, as the distance between the surface of the body and the PA is shorter, and there are no muscles in the way. In addition, the front of the PA is surrounded by the fibula and tibia, and there is a crural interosseous membrane between the fibula and tibia. Compared with compression hemostasis of the brachial artery, it is possible to apply pressure from both sides without soft tissue in between, and because there is a lot of interosseous membrane and ligaments around the puncture site, the risk of hematoma expansion is considered low. In this study, more than half of the cases underwent compression hemostasis from the body surface after balloon hemostasis from within the blood vessel. However, no hematoma formation was observed in patients who did not receive balloon hemostasis. Considering that the only method of hemostasis for the brachial artery approach is external pressure hemostasis and that the anatomical structure around the puncture site is more favorable for hemostasis in the PA, it is possible that hemostasis after anterolateral PA puncture can be achieved with external pressure hemostasis alone.

This study was conducted at a single institution and involved a small number of cases. In order to evaluate the safety of the wide-diameter sheath and the necessity and usefulness of balloon hemostasis from within the blood vessel, it is necessary to evaluate this on the basis of a prospective two-group comparison. However, the limitation of this study is that it is a retrospective evaluation of a small number of cases. It is necessary to accumulate more cases in the future, and if possible, it would be desirable to conduct a two-group comparison of the small- and wide-diameter sheaths and a comparison of the presence or absence of balloon hemostasis at the time of sheath removal.

Conclusions

Insertion of a 4.0–6.0 Fr sheath via anterolateral PA puncture did not result in any bleeding-related complications. It is hoped that the safety of using a large-diameter sheath in an anterolateral PA puncture approach will be recognized and that this will expand the range of treatment strategies for the distal artery approach.