Purpose

Localized prostate cancer is treated with surgery, radiotherapy (RT), and endocrine therapy. RT includes external beam RT (EBRT), high-dose-rate brachytherapy (HDR-BT), low-dose-rate brachytherapy, carbon ion therapy, and proton therapy. Since the 1990s, HDR-BT has been used to improve local control rates [1, 2]. However, long-term outcomes in high-risk patients remain sub-optimal, highlighting the need for further improvements [3-6]. Hydrogel spacers (HS) increase the prostate-rectum distance, improve rectal dose-volume histograms (DVH), and reduce radiation proctitis [7, 8]. However, its use involves challenges, such as invasiveness, cost, and potential complications. Therefore, careful patient selection for HS placement is essential, and research on optimizing patient selection criteria is ongoing [9, 10].

In HDR-BT, HS reduces rectal V30%-V80% and alleviates acute and late grade 1 rectal toxicities. However, few studies have examined whether HS improves the dose distribution within planning target volume (PTV) or the prostate [11, 12]. This study evaluated the impact of HS on the PTV, rectal, and urethral doses in HDR-BT as well as explored conditions, in which HS is most beneficial.

Material and methods

Human subjects

This retrospective observational study included 28 consecutive patients with prostate cancer, who underwent HDR-BT with HS placement at a tertiary care hospital between November 2019 and March 2024. Patients with unfavorable intermediate- to high-risk localized prostate cancer without urinary obstruction were included. HS employed in this study was SpaceOAR® (Boston Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). For cases with seminal vesicle invasion, HS was used only when no extension in dorsal lesions was detected on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Disease staging was determined according to the TNM classification (UICC, 8th edition), and risk stratification was performed using the National Comprehensive Cancer Network risk classification (version 4.2019). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the authors’ institution (approval No. 2021-0379).

Radiation therapy

Of the 28 patients included in this study, 27 received combined therapy with EBRT and HDR-BT, whereas one patient, who had undergone bilateral femoral head replacement and could not tolerate EBRT, received HDR-BT alone. In 25 patients, HDR-BT was administered following EBRT, with a mean interval of 9 days between the completion of EBRT and initiation of HDR-BT. EBRT (39 Gy/13 fractions) was delivered using intensity-modulated RT (IMRT) or three-dimensional conformal RT, with irradiation field determined according to the T classification. HDR-BT was performed using the Flexitron HDR system (Elekta, Stockholm, Sweden) with the following dose fractionation schedules:

EBRT + HDR-BT: 18 Gy/2 fractions/1 day (equivalent dose in 2 Gy fraction – EQD2: 54 Gy; total EQD2 for EBRT + HDR-BT: 104 Gy).

HDR-BT alone: 42 Gy/6 fractions/3 days (EQD2: 102 Gy).

EQD2 was calculated with an α/β ratio of 1.5 [13, 14]. A minimum interval of 6 hours was maintained between HDR-BT fractions.

Treatment planning

Treatment planning images were acquired using computed tomography (CT, Aquilion Lightning, Canon Medical Systems Corporation, Tochigi, Japan), with a slice thickness of 2 mm and a field of view of 25 cm. CT data were imported into Eclipse version 15.5 (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA, USA), while structures (the prostate, seminal vesicles, rectum, urethra, bladder, and HS) were contoured. Clinical target volume (CTV) included the prostate ± seminal vesicles according to the stage, with a margin applied as per institutional protocol. PTV was defined as equivalent to the CTV. All structures were contoured independently by a physician with over 5 years of experience in radiation therapy, and reviewed by two board-certified radiation oncologists with over 10 years of experience. The contoured CT data were transferred to treatment planning system Oncentra Brachy version 4.6.2 (Elekta, Veenendaal, Netherlands), and plans were generated using inverse-planning simulated annealing (IPSA) algorithm. To mitigate the influence of planner expertise, treatment plans were generated with only one optimization run without manual adjustments. The optimization parameters used are summarized in Table 1. For each patient, two treatment plans were created:

With HS: based on actual patient data with a HS in place.

Without HS: simulating the absence of a HS.

Table 1

Optimization criteria by inverse planning simulated annealing

| For PTV | cGy | Weight | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PTV | |||

| Surface | Min 900 | 200 | |

| Volume (D100%) | Min 900 | 100 | |

| For OARs | cGy | Weight | |

| Rectum | |||

| Surface | Max 700 | 1 | |

| Volume (D100%) | Max 600 | 180 | |

| Urethra | |||

| Surface | Min 1,000 | 1 | |

| Volume (D100%) | Min 1,000 | 150 | |

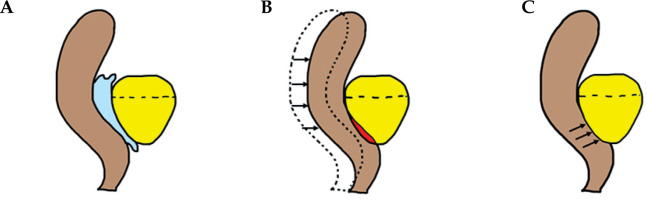

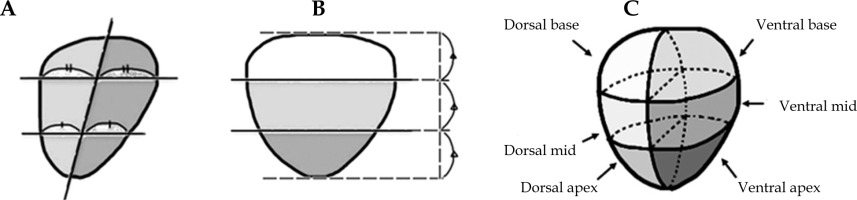

For the plans without HS, the rectal contour was adjusted anteriorly to approximate pre-HS anatomy (Figure 1). The plans were generated using IPSA using standardized institutional parameters (Table 1). The prostate was divided into the following six regions, and V100% and D90% for each region were evaluated: ventral apex, ventral mid, ventral base, dorsal apex, dorsal mid, and dorsal base. The method of region division is illustrated in Figure 2, and a 3D visualization of the segmented regions is shown in Figure 3.

Fig. 1

Creating plans without hydrogel spacer that corrects the backward movement of the rectum. A) Structures of the rectum, hydrogel spacer, and prostate (from left to right). B) Move the rectum to touch the prostate. C) Then, cut the lapping part

Fig. 2

The prostate was divided into two equal parts using A) the sagittal views and into thirds using B) the coronal view, and C) the overlapping part of each was divided into six areas

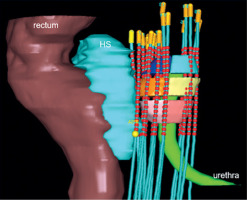

Fig. 3

Six regions of the prostate, hydrogel spacer, and organs at risk. Pink – ventral apex, Yellow – ventral mid, Light blue – ventral base, Light pink – dorsal apex, Orange – dorsal mid, Blue – dorsal base. The following parameters were also evaluated: (1) PTV and the entire prostate: V100%, V150%, and D95%; (2) Rectum: D0.1cc, D2cc, D5cc, and V100%; (3) Urethra: D0.1cc

In addition to the primary evaluation, the following parameters were analyzed as secondary endpoints:

V100 (%), V150 (%), and D95 (%) for both the PTV and entire prostate.

D0.1 (cc), D2 (cc), D5 (cc), and V100 (%) for the rectum.

D0.1 (cc) for the urethra.

The shortest distance from the dorsal surface of the prostate to the anterior wall of the rectum (prostate-rectum distance) was measured, and the correlation between the site-specific prostate-rectum distance and dosimetric parameters was analyzed in both groups with and without HS. The prostate-rectum distance was assessed using axial images from the treatment planning CT at the central slice in the cranio-caudal direction for each of the apex, mid, and base regions of the prostate.

Statistical analysis

A total of 60 treatment plans were generated from data of 28 patients (27 patients × 2 plans + 1 patient × 6 plans = 60 plans). Although multiple treatment plans were available for the same patient, each plan was treated as independent data because of anatomical variations caused by applicator position shifts, prostate edema, rectal stool accumulation, and bladder volume changes during an interval of at least 6 hours between the first and second irradiations. Paired t-tests were performed to analyze the evaluation parameters between the groups with HS and without HS. Significance was determined using a two-sided test with a p-value threshold of ≤ 0.05. Statistical analyses were done using EZR software version 1.68 [15]. In addition to significance, effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d [16], interpreted according to Sawilowsky [17]. Cohen’s d was calculated using the following formula:

where Ma and Mb are the means of the two groups, and SDa and SDb are their standard deviations.

d ≥ 1.2 indicated very large difference, 0.8 ≤ d < 1.2 – large difference, 0.2 < d < 0.8 – moderate difference, and d ≤ 0.2 – small difference.

For other endpoints, paired t-tests were similarly performed, with a p-value of ≤ 0.05 considered significant. Cohen’s d was also calculated for each parameter. Furthermore, compliance with the following dose constraints proposed in the 2020 Radiotherapy Planning Guidelines by the Japan Society for Radiation Oncology (JASTRO) was evaluated for PTV and organs at risk (OARs) [18].

PTV: D95% > 100%, V100% > 95%, V150% < 50%

Rectum: D0.1cc < 100%

Urethra: D0.1cc < 125%

Results

Patient background

The patient characteristics are summarized in Table 2. The majority were high-risk patients (96%), and all received neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy. No serious complications associated with HS placement were observed.

Table 2

Patient characteristics

Effect of HS on dose distribution

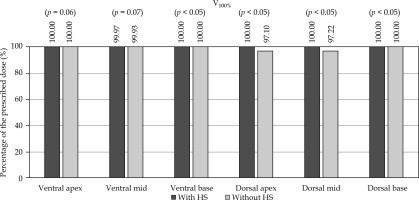

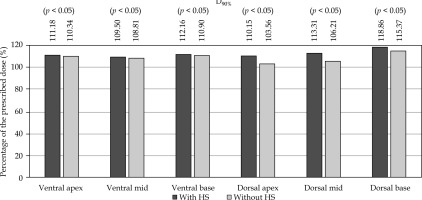

Tables 3 and 4 show each parameter and the analysis of the results. Figures 4 and 5 represent the results graphically.

Table 3

Median radiation dose to the target and organs at risk in patients with and without a hydrogel spacer

Table 4

Median prostate-rectum distance at the apex, mid-gland, and base in patients with and without a hydrogel spacer

In the dorsal regions, HS significantly improved V100% and D90%, particularly at the apex and mid (p < 0.05, large effect sizes). At the base, minimal improvements were observed, and the ventral regions showed little change. HS significantly increased the prostate-rectum distance, especially at the apex and mid (very large effect sizes).

The PTV and prostate coverage (V100%, D95%) improved significantly with HS, with higher compliance with JASTRO constraints (compliance rates improved from 68.3% to 88.3% with HS placement). Although V150% increased slightly, it remained acceptable. Rectal doses (D0.1cc, D2cc, D5cc, V100cc) were significantly reduced with HS, and all cases met the JASTRO D0.1cc constraint compared with 23.3% without HS. No significant differences were noted for the urethra dose.

Discussion

Prostate cancer has a low α/β ratio of approximately 1.5, making HDR-BT an effective boost when combined with EBRT, resulting in an improved biochemical recurrence-free survival (bRFS) [4, 19]. This study demonstrated that HS further optimized dose distribution, particularly in anatomically relevant regions. The most pronounced benefit was observed in the dorsal apex and dorsal mid regions of the prostate, the area close to the rectum where rectal sparing is critical. Importantly, the peripheral zone, a common site of cancer occurrence [20], demonstrated improved coverage with HS. In addition, the FLAME trial reported that dose escalation to intra-prostatic lesions improved the 5-year bRFS [21], supporting the clinical advantage of HS usage in focal dose-escalation strategies to these regions. Moreover, HS improved PTV coverage and JASTRO compliance rates, although V150% increased slightly. Clinically, this suggests a better balance between coverage and conformity, despite a modest rise in hot spots.

For OARs, the rectal doses were significantly reduced, in agreement with prior reports [11, 12], supporting the clinical benefit of HS in reducing rectal toxicity. In contrast, the urethral doses showed no significant change, likely reflecting the IPSA weighting that prioritizes urethral sparing regardless of HS use.

Several limitations must be noted. First, rectal delineation was based on a virtual model, which may not reflect the actual rectal anatomy. Second, CT-based contouring was employed, whereas MRI could provide higher accuracy. Third, the same optimization parameters were applied to both groups, despite anatomical differences with and without HS. This approach could underestimate the true benefit of HS for the PTV dose coverage. Future studies should incorporate additional plans, in which OAR DVHs are standardized, and evaluate whether the resulting dose distributions are clinically acceptable.