Purpose

Eyelid tumors are rare, comprising 3-5% of the head and neck skin cancers, with an annual incidence of approximately 15 per 100,000 cases [1]. Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common sub-type, followed by squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and less frequent but more aggressive, sebaceous gland carcinoma (SGC) [2-4]. While BCC is typically indolent, SCC and SGC carry a higher risk of local recurrence and metastasis, with SGC posing a particularly poor prognosis if not diagnosed early. Most tumors arise in the lower eyelid and inner canthi, emphasizing the need for early detection to improve patient outcomes [5-9].

Managing eyelid tumors requires a multidisciplinary approach to balance disease control with preservation of function and esthetics in this anatomically sensitive region. Surgery remains the primary treatment modality; however, radiation therapy plays a vital role in post-operative setting, and can serve as a definitive treatment in selected cases. Advances in external beam radiation techniques, such as intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), have improved precision, but complications, such as dry eye syndrome, skin discoloration, telangiectasia, ocular surface damage, and visual deterioration, remain significant concerns [10-13].

Interstitial brachytherapy (ISBT), a form of interventional radiotherapy (IRT), offers a highly targeted and effective treatment modality for achieving excellent local control while minimizing long-term complications. By delivering a high radiation dose directly to the tumor bed, ISBT/IRT ensures superior dose conformity, creating a steep dose gradient that effectively spares adjacent critical structures. This precision is particularly beneficial in treating small, anatomically complex areas, such as the eyelid and periocular region, where the preservation of function and esthetics is paramount. In addition to optimizing tumor coverage, ISBT offers logistical advantages by shortening treatment duration compared with protracted external beam therapy, enhancing patient convenience and compliance.

Our study evaluated the clinical experience of high-dose-rate (HDR) ISBT/IRT in patients with non-basal cell histologies who underwent surgery. By precisely targeting the tumor bed, HDR-ISBT/IRT optimizes dose distribution while reducing treatment-related toxicity. These advantages highlight ISBT/IRT as a valuable therapeutic option for eyelid skin carcinomas, offering improved oncological outcomes with better cosmetic and functional preservation.

Material and methods

Study design and eligibility

This retrospective study was conducted among patients with eyelid malignancies treated between August 2007 and August 2024 at the Tata Memorial Centre, India. All patients with histologically confirmed eyelid cancers were screened, focusing on rare and more aggressive histologies, such as SCC, SGC, and salivary gland carcinoma, while excluding more common BCC. Only de novo diagnoses were included in this cohort; recurrent cases were excluded.

Patient data were retrieved from the institute’s electronic medical records (EMR) for analysis of key clinical and pathological variables. All patients provided written informed consent prior to radiotherapy, with permission for clinical photography for response evaluation and potential use in research and publications. The study was conducted in accordance with institutional ethical guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki, and Good Clinical Practice.

All included patients were evaluated in a dedicated multidisciplinary tumor clinic through comprehensive clinical and radiological assessments. Staging was performed using the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 8th edition. Local disease extent, including the depth of invasion, was assessed using diagnostic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck region. For multifocal tumors, largest tumor diameter was recorded as the primary tumor size. Distant metastatic workup was routinely performed, particularly for SGC patients, to rule out metastases. Patients with distant metastases at diagnosis were excluded from the study.

Primary surgery involved wide local excision, with ipsilateral lymph node dissection and parotidectomy as needed. Regional nodal dissection, with parotidectomy and/or neck dissection, was carried out when warranted by clinical or pathological findings. Reconstruction was performed as required, followed by a detailed histopathological examination. Post-operative ISBT was administered in all cases. To ensure optimal wound healing and tissue integrity, HDR-ISBT was initiated within 4 to 6 weeks post-surgery.

Implant technique, treatment planning, and delivery

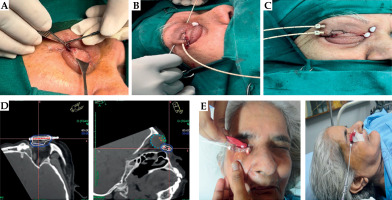

Implant procedure was performed under general anesthesia. Target volume for brachytherapy was defined based on pre-operative tumor extent and post-surgical scar. If there was a flap post-operatively, it was carefully evaluated by an ophthalmologist for appropriate division and closure, to ensure optimal healing and therapeutic outcomes (Figure 1A).

Fig. 1

A) Flap division by an ophthalmologist. B, C) Implant application with nylon tube insertion and replacement with catheters. D) Dose distribution. E) Custom-made spacer placed during treatment

Implant volume encompassed the primary disease site with a 3-5 mm margin adjusted as needed to maximize treatment effectiveness, while minimizing exposure to surrounding structures. Interstitial implant was performed using 16-gauge stainless steel needles, inserted with appropriate spacing to ensure even dose distribution. Plastic tubes were then placed through the needles, and secured in place after needle removal. Stability was maintained by anchoring the tubes to the skin using plastic buttons and beads (Figure 1B, C).

To minimize radiation exposure to adjacent healthy ocular structures, a personalized conformer was fabricated using dental prosthesis material (Figure 1E), whenever necessary. This conformer provided both protection and precision during radiation delivery. For treatment planning, high-resolution images were acquired using a dedicated CT simulator. Patients were positioned supine for stability, and images were captured with a slice thickness of 1-1.5 mm for detailed visualization and accurate target mapping.

Treatment planning was done using Oncentra Brachy treatment planning system (Elekta, Stockholm, Sweden), following the principles of the modified Paris system, also known as stepping source dosimetry. Treatment delivery was performed with a high-dose-rate (HDR) afterloader system using an iridium-192 (192Ir) source (Elekta Nucletron). A reference isodose line (85% or 100%) was selected based on tumor bed coverage and proximity of critical structures, such as the skin and cornea. As specific organ at risk (OAR) constraints were not defined in our protocol, the ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) principle was employed for all identifiable OARs (Figure 1D).

Treatment protocol consisted of a total dose of 21-49 Gy, delivered in 7-14 fractions at 3-3.5 Gy per fraction, with two fractions administered daily, separated by a 6-8-hour interval. Local anesthetic spray was applied to the treatment region before each session to minimize discomfort. Antibiotic ointment dressing and oral analgesics were applied as needed.

Toxicity and follow-up

Patients were closely monitored daily during ISBT, and reviewed one month after completing radiotherapy. Follow-up assessments were conducted every three months for the first two years, every six months until five years, and annually thereafter. Photographic documentation and radiological imaging were performed as needed for detailed evaluation. Special attention was given to visual function, skin integrity of the eyelid, conjunctival health, and overall cosmetic outcomes. Acute toxicities were graded using the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) criteria, while late complications affecting the skin, eyelids, and vision, were evaluated according to the common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE), version 5.0.

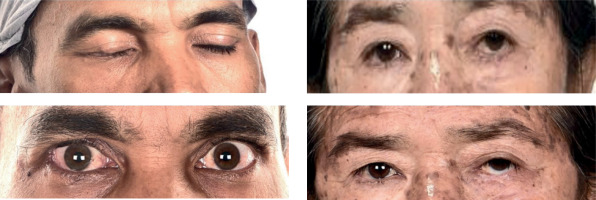

Cosmetic outcomes were systematically assessed with the CAIB scale, which evaluates six domains: skin depigmentation, eyelid dysfunction (ectropion or entropion), dry eye syndrome, keratitis, cataracts, and glaucoma. Each domain was scored as 1 (present) or 0 (absent), resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 6. Cosmetic results were categorized as excellent (0), very good (1-2), fair (3-4), or poor (5-6). The CAIB scale provided an objective measure of cosmetic outcomes, highlighting cosmetic effectiveness of HDR-ISBT [14]. The CAIB assessment was performed by the treating radiation oncologist for clinical parameters, while an ophthalmologist conducted the necessary eye examinations, including slit-lamp microscopy and tonometry, to assess ocular health. These examinations were essential for a comprehensive evaluation of eye-related outcomes and the overall cosmetic effect following treatment. This approach ensured that both functional and esthetic aspects were carefully monitored (Figure 2).

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint of this study was loco-regional control (LRC), defined as the time from completion of ISBT to the first clinical or radiological evidence of loco-regional recurrence at primary site or regional lymph nodes. Secondary endpoints included cosmetic outcomes, treatment-related toxicities, disease-free survival (DFS), and overall survival (OS). DFS was defined as the interval from completion of ISBT to any clinical or radiological evidence of recurrence or death from any cause. OS was measured from the date of histological diagnosis to death from any cause. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to estimate and visualize LRC, DFS, and OS. All patients who completed treatment were included in the survival analysis. Patients lost to follow-up were right-censored at the date of their last known clinical contact. Statistical analyses were performed using RStudio Desktop (version 2022.07.0+548), an integrated development environment for R (RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA, USA).

Results

Eighteen patients with eyelid tumors underwent HDR-ISBT between August 2007 and August 2024. The median age was 67.5 (IQR, 55-80) years, with a male-to-female ratio of 8 : 10. The most common histopathology was SGC (72.2%), followed by SCC (22.2%) and mucinous carcinoma (5.6%). Tumors were more frequently located in the lower eyelid (66.7%) than the upper eyelid (33.3%), with right-sided predominance (66.7%). The tumors were T1 in 8 patients (44.4%) and T2 in 10 patients (55.6%), graded according to the AJCC 8th edition staging system. Perineural invasion (PNI) was observed in one patient (5.6%). Surgical margin status was close in 44.4% (n = 8), positive in 11.1% (n = 2), and negative in 44.4% of patients (n = 8), while lymph node dissection was performed in 33.3% of cases (n = 6). The baseline clinico-histopathological characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1

Baseline characteristics of the patients

The median tumor size was 1.5 (range, 0.5-5.2) cm. The median ISBT dose varied across the cohort, with prescribed regimens of 49 Gy in 14 fractions, 39 Gy in 13 fractions, 35 Gy in 10 fractions, 24.5 Gy in 7 fractions, and 21 Gy in 7 fractions for post-operative treatment. Additionally, three patients received external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) to the parotid bed with a total dose of 60 Gy in 30 fractions using a conformal technique, ensuring that normal tissue tolerance limits were respected.

The median biologically effective dose (BED) was 47.25 (range, 27.3-66.15) Gy. The median V100, representing the volume receiving 100% of the prescribed dose, was 1.11 (range, 0.95-5.6) cc, while the median V150, indicating the volume receiving 150% of the prescribed dose, was 0.55 (range, 0.41-2.06) cc. Dose homogeneity index (DHI) had a median value of 0.65 (range, 0.55-0.69), suggesting moderate dose uniformity within the treated volume. The dosimetric analysis of the target volumes and critical OARs, including the cornea, lens, and lacrimal gland, is presented in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2

Treatment and target volume dosimetric parameters

Table 3

Organs at risk (OARs) dosimetry

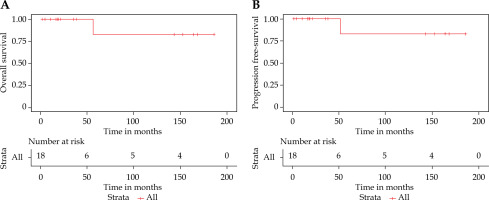

With a median follow-up duration of 21.93 (IQR, 10.60-152.83) months, no loco-regional recurrences (LRC) were observed among the patients on regular follow-up. At the time of analysis, 13 patients remained disease-free. Amongst the remaining five patients, two had died: one due to COVID-19-related acute respiratory illness and the other from systemic disease progression. Additionally, three patients became untraceable after substantial clinical follow-up (18.2, 35.9, and 38.8 months, respectively). These patients were censored at their last documented follow-up in the Kaplan-Meier analysis. The 5-year OS and progression-free survival (PFS) rates were both 83.3% (95% CI: 53.5-100%). Figure 3A and B presents the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for OS and PFS.

Fig. 3

Kaplan-Meier curves showing (A) overall survival and (B) progression-free survival differences

Cosmetic outcomes were evaluated using the CAIB scale at the most recent follow-up. Cosmesis was rated as excellent in 10 patients (55.55%) and very good in 8 patients (44.44%). No patients had fair or poor cosmetic outcomes, demonstrating cosmetic safety of HDR-ISBT. Skin toxicity was generally mild. Moreover, grade 1 erythema was observed in 12 patients, while one patient experienced grade 2 desquamation. Grade 1 mucosal reactions (mild epiphora) were seen in 5 patients; all managed with symptomatic treatment. No grade 3 or higher acute toxicities were observed.

Late toxicities were minimal. Eyelid and eye function were preserved in 88.88% (n = 16), with organ preservation in all cases. Two patients experienced worsening of vision compared with baseline. One patient required surgical correction for lower-lid ectropion. Importantly, no cases of ulceration, perforation, or necrosis of soft tissue, cartilage, or bone were reported. The detailed data on acute and late toxicities are provided in Table 4. Overall, HDR-ISBT demonstrated favorable outcomes in terms of both disease control and cosmetic preservation for eyelid malignancies.

Table 4

Toxicities and cosmesis using IBRT

Discussion

The management of eyelid cancers requires a careful balance between effective tumor control and preservation of functionality and esthetics. Several factors influence treatment selection, including patient-specific considerations (age, comorbidities, personal preferences, and performance status), tumor-related features (size, location, and depth of invasion), and treatment factors (efficacy, complication rates, and cosmetic outcomes). This study presented an updated analysis of our previous work on post-operative interstitial brachytherapy for eyelid cancer [14]. On the bases of prior findings, we incorporated recent advancements in technique, improved patient outcomes, and refinements in treatment efficacy, providing new insights that contributed to the evolving landscape of eyelid cancer management. Over the study period, several key technical and procedural refinements were introduced. The stepping-source HDR approach with modified Paris system planning, enabled more precise dose modulation, improving conformity around critical ocular structures. In recent years, the use of custom-made conformers became a standard, offering additional protection for the cornea and lens. Implant stability was improved through better fixation techniques using anchoring beads and buttons, enhancing reproducibility. A uniform post-operative dose protocol of 49 Gy in 14 fractions (3.5 Gy twice daily) was adopted in later patients, optimizing tumor control and toxicity outcomes based on BED modelling. Cosmetic evaluation was strengthened by consistent application of the CAIB scale. Furthermore, the incorporation of multidisciplinary tumor board and adherence to ALARA-based planning for organs at risk (OARs), contributed to the enhanced overall treatment quality and safety. These refinements reflect the progressive evolution of the technique and institutional learning over time.

In the current cohort of 18 patients treated with HDR-ISBT, we observed an excellent LRC rate of 100%, with no instances of disease recurrence in cases on regular follow-up. These findings are consistent with existing literature, reporting LRC rates of 90-100% following surgery or radiotherapy [14-19]. In a study by Fitzpatrick et al. [20], doses ranging from 35-50 Gy were delivered using conventional external beam techniques. These are considered sub-optimal by current standards, particularly in high-risk histologies, due to limited dose conformity and lack of image guidance. Notably, no patients had medial canthus involvement or recurrent disease; all cases were de novo diagnoses. This further reinforces HDR-ISBT as an effective modality for eyelid malignancies, providing high tumor control while preserving critical functions and esthetics. A 2015 systematic review of six studies reported a median LC rate of 95.2% for brachytherapy, with favorable toxicity, functionality, and cosmetic outcomes [6]. Prognostic factors, such as medial canthus involvement, recurrent disease, sub-optimal radiation doses, positive surgical margins, perineural invasion (PNI), and high-grade histology, are associated with lower control rates [20, 21]. Despite these known risks, our study demonstrated excellent local control and acceptable toxicity, highlighting the efficacy of HDR-ISBT in managing these rare tumors.

Acute toxicities in our cohort were predominantly mild, with conjunctival erythema and epiphora as the most common reactions (primarily grade 1). No patients experienced grade 3 or higher acute toxicities. Moreover, late toxicities were also limited, with hyperpigmentation as the most frequently observed (n = 6). Persisting eyelid deformities requiring surgical correction (ectropion release) were seen in two patients, while two other cases developed madarosis. Importantly, these late toxicities were mostly grade 1-2, aligning with outcomes from other HDR brachytherapy studies [14].

Historically, conventional EBRT for periocular malignancies has been associated with significant ocular toxicities. Radiation-induced dry eye, telangiectasia, madarosis, and corneal perforation, occur at increasing frequencies with doses exceeding 30-60 Gy [22-25]. In contrast, HDR-ISBT allows for precise dose delivery to the tumor bed, minimizing exposure to surrounding critical structures. In our series, no severe complications, such as cataracts, lacrimal duct stenosis, glaucoma, or corneal ulceration were observed, underscoring the safety and efficacy of this technique when meticulously planned and delivered.

Our study administered doses ranging from 21 to 49 Gy over 7 to 14 fractions, tailored to individual clinical indications, while dose and fractionation were individualized based on tumor and surgical factors. Key determinants included tumor size, histologic grade, depth of invasion, margin status, presence of perineural invasion (PNI), and extent of reconstruction. Low-risk cases, such as small, well-differentiated tumors with negative margins, were typically treated with shorter regimens (e.g., 3 Gy × 7-10 fractions). Intermediate-risk cases, with close margins or minor risk factors, i.e., PNI or lymphovascular invasion, received 3.5 Gy × 10 fractions. High-risk features, such as involved margins, high-grade histology, or multifocality, warranted dose intensification (e.g., 3.5 Gy × 12-14 fractions). For example, complex reconstructions or nodal disease resulted in higher total doses (up to 49 Gy in 14 fractions), whereas superficial tumors with favorable pathology were treated with lower doses to balance efficacy and toxicity.

The median biologically effective dose (BED) with an α/β ratio of 10 was 47.25 Gy, closely aligning with reported regimens by Mareco et al. [15]. Emerging strategies, such as hypofractionated HDR-ISBT, as proposed by Hennequin et al., may further enhance outcomes by intensifying the dose per fraction while limiting toxicity due to small treatment volume [26]. The advent of 3D printing for customized applicators is promising for improving treatment precision and overall cosmetic results. Emerging innovations, such as 3D-printed patient-specific applicators, may offer enhanced anatomical conformity, particularly for complex periocular geometries. These tools have the potential to improve dose precision, reduce operator dependency, and further optimize cosmetic outcomes. Future studies are warranted to explore their clinical utility in eyelid brachytherapy [27-30].

Reports on post-operative brachytherapy for eyelid cancers are sparse, with most studies including heterogeneous patient populations in terms of both histology (squamous and basal cell carcinoma) and brachytherapy type (radical or post-operative). Our study focused on post-operative HDR-ISBT, demonstrating excellent-to-good cosmetic outcomes based on the indigenous CAIB scale. This reflects the importance of standardized cosmetic assessment in evaluating late outcomes. Variable cosmetic results have been reported across different institutions, but our findings are consistent with other series using HDR interstitial brachytherapy for eyelid carcinomas (Table 5).

Table 5

Literature review for adjuvant HDR interstitial BT of the eyelid

| Authors [Ref.] | Year | No. of patients | HPE | T stage | Treatment | Total dose and fractionation | Median follow-up | Outcomes and cosmesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laskar et al. [14] | 2015 | 8 | SGC: 50% SCC: 37.5% BCC: 12.5% | T4: 37.5% Other than T4: 62.5% | Adjuvant: 100% | 21-35 Gy (3 Gy BID for 7# to 3.5 Gy BID for 10#) | 35 | LC: 100% Cosmesis Excellent: 5 pts. Good: 2 pts. |

| Mareco et al. [15] | 2015 | 17 | SCC: 94% BCC: 6% | Tis: 6% T1: 46% T2a: 18% T2b: 18% T3a: 12% | Definitive: 12% Adjuvant: 71% Salvage: 18% | 32-50 Gy, in 9-11# | 40 | LC: 94.1% Cosmesis Excellent: 5 pts. (29%) Good: 7 pts. (41%) Satisfactory: 2 pts. (12%) |

| Cisek et al. [17] | 2021 | 28 | BCC: 86% SCC: 14% | T1: 82% T2: 18% | Definitive: 85% Adjuvant: 15% | 45-49 Gy in 5 Gy BID for 9# to 3.5 Gy BID for 14# | 24 | LC: 96.5% |

| Cuffaro et al. [19] | 2023 | 10 | SGC: 30% BCC: 30% SCC: 20% Melanoma: 20% | T2b: 10% T3b-c: 40% T4a: 50% | Adjuvant: 100% | 34-49 Gy in 3.4 Gy BID for 10# to 3.5 Gy BID for 14# | 10 | LC: 80% |

[i] BCC – basal cell carcinoma, SCC – squamous cell carcinoma, hybridization, MCC – Merkel cell carcinoma, SGC – sebaceous gland carcinoma, LC – local control, RT – radiotherapy, Gy – Gray (unit of radiation dose); # fractions, BID – Bis in die (twice daily), HPE – histopathological examination, T stage – tumor stage (TNM-based staging system)

A previous study from our institute by Budrukkar et al. evaluated HDR-ISBT, primarily including BCC and SCC across various periocular subsites. While that study focused on local control, organ preservation, and toxicity outcomes, our current analysis specifically assessed post-operative ISBT in rare histologies, such as SGC and salivary gland carcinoma. Unlike the prior study, which included definitive and salvage brachytherapy, the current research exclusively evaluated ISBT following surgery. Despite differences in patient selection and treatment setting, both studies demonstrate high local control rates, organ preservation, and good-to-excellent cosmetic outcomes, highlighting the role of ISBT in periocular malignancies [31].

Apart from the clinical outcomes, it is important to consider broader systemic factors affecting the implementation of brachytherapy into routine practice. Despite its proven clinical efficacy and continuous technological innovation, the utilization of brachytherapy remains inconsistent across institutions and tumor sites. This underuse is often attributed to complexity of the technique, limited access to dedicated facilities, and a lack of formal training among radiation oncologists. Recent evidence underscores the necessity of integrating brachytherapy into modern interventional oncology practices through specialized centers and multidisciplinary tumor boards, which have demonstrated enhanced treatment personalization and patient outcomes [32, 33]. Moreover, the evolution of head and neck brachytherapy techniques requires both technical refinement and institutional support, in order to be effectively translated into clinical practice [27]. Integrating interventional radiotherapy into modern oncology workflows, particularly high-volume centers, is essential not only for advancing patient care, but also for enhancing the education and training of future clinicians [30]. Our findings support this vision, emphasizing the importance of delivering brachytherapy within experienced, multidisciplinary environments, to ensure optimal outcomes and sustainability of the technique.

A major strength of our study is the consistent treatment protocol and the systematic evaluation of outcomes, including loco-regional control, cosmetic results, and toxicity. The use of a cosmetic scale (CAIB) offered a structured method for assessing cosmetic outcomes, even though its application was limited. Additionally, the detailed dosimetric evaluation and long-term follow-up provided valuable insights into the safety and efficacy of HDR-ISBT.

However, this study has inherent limitations. As a single-center, retrospective study, it is prone to selection and reporting biases. Also, the relatively small sample size reflects the rarity of these tumors and limits the generalizability of the findings. The prolonged accrual period (17 years) introduces potential variability in patient management and follow-up practices. Moreover, the absence of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) is a notable limitation, as they could have provided a more comprehensive perspective on functional and cosmetic outcomes.

Conclusions

Eyelid tumors, although rare, pose significant challenges in clinical management due to their unique anatomical location and potential for local aggressiveness. HDR-ISBT offers an effective post-operative treatment option, achieving excellent local control, favorable survival outcomes, and good-to-excellent cosmetic results. The precise dose delivery and short treatment duration make it particularly suitable for periocular tumors, minimizing toxicity while maintaining tumor control. Based on this experience, we propose a risk-adapted approach to post-operative dosing, to optimize oncologic outcomes while preserving cosmetic and functional results. A multidisciplinary methodology remains essential to ensure personalized care and optimal outcomes for patients with these complex malignancies.