Purpose

India accounts for one-third of global burden of oral cancer [1], where it is the commonest malignancy among men and fourth most common cancer among women [2-4]. The most common is loco-regional presentation with advanced stage, and almost 15-20% of cases present with an early-localized disease [1, 4]. The management of early-stage oral cancer presents a unique challenge, as it requires balancing disease control with the preservation of integral functional abilities [5]. Although surgical excision is often considered as standard treatment approach [6, 7], but associated morbidities, particularly the impairment of speech, chewing, and swallowing, can affect the overall functional outcomes [8-10].

In this context, even though organ preservation approach with radiotherapy, specifically with brachytherapy, shows reasonably good oncological and functional outcomes [11-13], the overall utilization of brachytherapy in head and neck cancer has declined over the last couple of decades [14, 15]. This gap further widens in a new setup, where external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) is often preferred over brachytherapy [16, 17].

Tata Memorial Centre (TMC) stands as India’s leading institution dedicated to the comprehensive management of cancer. To extend the care nationwide, TMC has established eight new cancer centers across India [18]. In our setup, comprehensive cancer care services, including radiotherapy, were commissioned in 2019-2020. In this paper, we shared our experience in addressing challenges from installation to clinical application of interstitial brachytherapy (ISBT) in early-stage oral cancer, along with initial clinical outcomes.

Material and methods

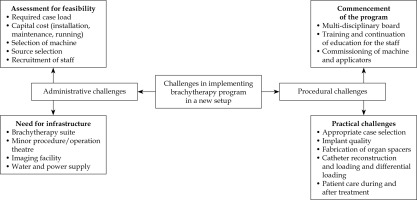

Challenges in implementing interstitial brachytherapy program in oral cancer

In 2020, during the peak of COVID-19 pandemic, our institution established a brachytherapy suite, initially focusing on gynecological cancers. The practice was later extended to other malignancies, including head and neck cancers. We developed a comprehensive workflow for case selection, and refined various processes (Figure 1).

Administrative needs

An integrated brachytherapy suite, including a minor procedure room, treatment planning area, and an adequately shielded treatment room, was established nearby. Cobalt-60 (60Co) source was chosen for logistical advantages in a remote facility, particularly due to its longer half-life compared with widely used iridium-192 (192Ir) source [19, 20]. In addition to the capital investment, personnel were trained at each level by experienced staff, with rotations at the established facilities when necessary. Careful execution and regular quality checks were conducted as the processes were streamlined.

Clinical applicability

Existing national [21] and international [22, 23] guidelines were reviewed, and Indian Brachytherapy Society (IBS) guidelines [21] published in the year 2020 were employed as benchmark for developing standard operating procedures (SOPs) and selecting appropriate cases for ISBT. All patients deemed suitable for ISBT underwent a thorough evaluation by a multidisciplinary team (MDT), involving head and neck surgeons, dental surgeons, radiologist, speech and swallow therapist, radiation oncologists as well as patient and his/her caregiver. Therefore, a collaborative informed decision was made to determine the initial choice of treatment, between surgery and brachytherapy.

Procedure-related challenges

All patients underwent implant placement according to IBS guidelines [21]. In addition to the guidelines published, the following procedures were done.

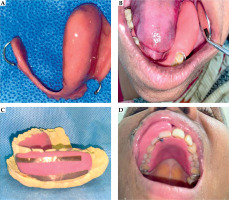

Use of clinical drawing templates and documentation of the disease:

To better describe the disease topography, clinical drawing template was used. An example of documented clinical findings and disease topography, with corresponding clinical photographs, is shown in Figure 2.

Use of intra-oral ultrasound:

Along with utilization of MRI, a cost-effective intra-oral ultrasound (io-US) to estimate depth of infiltration (DOI) in oral tongue cancer cases was used.

Use of silver markers:

Silver markers were placed during ISBT procedure at the disease boundaries to assist in defining the reference isodose.

Utilization of intra-oral spacers:

Intra-oral spacers were appropriately placed at the time of implantation. Initially, rubber tubes or dental wax were used. However, with growing experience and expertise, we started fabricating customized acrylic shields (Figure 3).

Use of advanced EBRT for nodal irradiation:

Since primary radiotherapy was the sole treatment modality, we opted to use EBRT for elective nodal irradiation (ENI) when needed [24-27]. ENI was performed using volumetric modulated arc (VMAT) and 3-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT) technique, allowing sparing of adjacent organs at risk (OARs), such as the bilateral parotids, laryngeal framework, pharyngeal constrictors, and spinal cord.

Fig. 2

A) Clinical drawing template used for documentation of disease in oral tongue cancer patient. B) Clinical drawing at initial evaluation. C) Corresponding patient’s clinical photograph at brachytherapy. D) Clinical drawing at brachytherapy evaluation. E) Corresponding patient’s clinical photograph at brachytherapy

Fig. 3

A) Fabricated spacer for tongue cancer by using cold cure acrylic resin. B) Intra-oral fitting of acrylic shield in tongue cancer patient in lower jaw on the left side. C) Using of copper film over spacer for improved identification in planning CT scan for a patient with upper lip primary. D) Placement of intra-oral spacer in patient in upper jaw for upper lip primary case

Implementation in clinical practice

In August 2020, ISBT program for oral cancer was initiated, and till July 31, 2022, 18 patients (oral tongue = 13, lip = 3, buccal mucosa = 2) were treated.

Treatment characteristics

External beam radiotherapy

All patients with oral tongue (n = 13), one with lip, and one with buccal mucosa cancers received ENI by EBRT prior to ISBT. EBRT was delivered for all oral tongue cases using VMAT, and other two non-tongue patients received 3D-CRT. EBRT treatment was delivered with Varian TrueBeam unit (v. 2.7) and image-guided radiotherapy (IGRT). In total, 3 patients (2 lip and 1 buccal mucosa) having proliferative primary tumor and tumor dimensions ranging from 1-2 cm (median, 1.5 cm), received ISBT alone. The dose fractionation schedule of EBRT and ISBT, and the cumulative EQD2 doses are shown in Table 1.

Interstitial brachytherapy

All ISBT implantation procedures were performed under general anesthesia. Hollow stainless-steel needles were inserted through sub-mental and sub-mandibular regions in tongue cases, and for lip and buccal mucosa patients, the needles were inserted in subcutaneous and sub-mucosal planes. The needles were then replaced with flexible polyurethane implant catheters (6 F, 30 cm). Additional beads were positioned at distal (non-connector) ends of the tubes to ensure adequate surface coverage as needed without crossing the catheters. Following the procedure, patients underwent a non-contrast CT scan with a slice thickness up to 1.25 mm. Clinical target volume (CTV) was contoured based on clinical examination findings, silver marker placements, and radiological imaging. To ensure adequate coverage of the dorsal surface of the tongue, the first dwell position was placed above the surface (Figure 4). ISBT was delivered with a cobalt (60Co) high-dose-rate (HDR) source using a remote controlled afterloader Flexitron (Nucletron, Elekta AB, Stockholm, Sweden) twice a day, with at least 6 hours gap between fractions. Median dose and fractionation schedule for ISBT boost cases were 22.5 Gy in 5 fractions, while for radical ISBT, the doses varied from 40 Gy in 10 fx. to 49.5 Gy in 11 fx. Brachytherapy source strength ranged from 1.9 to 1.3 Ci. Median total reference air kerma (TRAK) of treatment plans was 0.089 cGy at 1 m (range, 0.026-0.129 cGy at 1 m).

Table 1

Treatment characteristics (n = 18)

Fig. 4

Images of a tongue cancer patient demonstrating ISBT dose distribution. A) With intra-oral spacer (marked in cyan), CTV (red), and B) mandible (brown) abutting intra-oral spacer. C) Avoidance of high-dose regions in the mandible with a use of spacer. D-F) Dose color-wash in sagittal, axial, and coronal sections, respectively

Clinical outcomes and statistical considerations

Clinical outcomes were evaluated in terms of response rates, loco-regional control (LRC), and overall survival (OS). Patients with complete clinical resolution of the disease at 3 months post-treatment were classified as achieving a complete response. LRC and OS were calculated from the date of treatment initiation. Data collection continued until March 31, 2024. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 29.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Clinico-demographic profile

The median age of the cohort was 55 years (range, 29-75 years), with two-third of patients being males. The majority had T1 primary (n = 13, 72.2%), and the most common growth pattern was infiltrative (72.2%). Additional clinico-demographic profile is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

Patient clinico-demographic profile (n = 18)

Treatment characteristics and acute toxicity profile

The treatment characteristics are detailed in Table 1. The median dose and fractionation used for EBRT was 50 Gy in 25 fractions (fx.), and the median duration of treatment was 35 days (range, 32-40 days). According to Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) classification, the most common cumulative toxicities during EBRT were dermatitis (grade 1 in 13 patients, 86.7%; grade 2 in 2, 13.3%), mucositis (grade 1 in 6, 40%; grade 2 in 9, 60%), and esophagitis (grade 1 in 12, 80%; grade 2 in 2, 13.3%; grade 3 in 1, 6.7%).

ISBT implants were performed at a median gap of 25 days (range, 14-47 days). The median number of needles placed was 9 (range, 4-15), across median 2 (range, 1-3) planes. Additional ISBT treatment characteristics are presented in Table 1. An intra-oral spacer was applied in 12 cases (66.7%). For patients receiving EBRT followed by ISBT, the median equivalent doses in 2 Gy per fx. (EQD2) was 74 Gy (range, 69-77.5 Gy EQD2). The median overall treatment time for combined EBRT and ISBT boost was 67 days (range, 47-88 days). Post-ISBT, the highest reported toxicities were mucositis (grade 1 in 10 patients, 55.5%; grade 2 in 6, 33.3%; grade 3 in 2, 11.2%) and dysphagia (grade 1 in 12 cases, 80%; grade 2 in 2, 13.3%; grade 3 in 1, 6.7%). Various dosimetric indices regarding ISBT are reported in Table 3 and Supplementary Table 1.

Table 3

Clinical target volume coverage, mandibular doses, and various dosimetric indices for ISBT cases (n = 17)

[i] ISBT – interstitial brachytherapy, SD – standard deviation, CI – coverage index, DHI – dose homogeneity index, DNR – dose non-homogeneity ratio, OVI – overdose volume index, EBRT – external beam radiotherapy, N.R. – not reported, * one lip patient with poor geometry was not included in the table, but values are presented in text

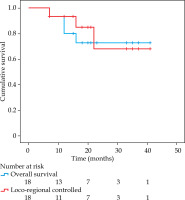

Clinical outcomes

The median follow-up of the study was 32 months (interquartile range [IQR]: 21-36 months). Complete response was attained in 17 patients (94.44%), and residual disease was noted in one patient. The overall 3-year LRC was 67.9% and OS was 72.7% (Figure 5). The predominant pattern of failure was local failure (LF) seen in 4 patients (22.2%), 2 patients experienced loco-regional failure (LRF), and 1 developed combined local and distant failure (lung metastases) (Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 5

Overall loco-regional control of patients treated with interstitial brachytherapy with or without EBRT

Six patients underwent salvage surgery (one with post-ISBT residual disease, and five tongue cancer patients with LF). Surgery could salvage all patients, but one had microscopic positive margins. One patient did not opt for surgery, and one with distant metastasis was treated with palliative intent. Post-salvage surgery, one tongue cancer patient experienced a second LRF after 5 months and underwent re-surgery; the patient was disease-free at last follow-up at 22 months. There were a total of 5 deaths: 2 due to progressive disease and 3 from intercurrent illnesses.

Long-term toxicity profile

The naso-gastric tube was removed at the completion of brachytherapy, and all patients resumed oral feeding immediately, except for one patient who required naso-gastric feeding for additional two weeks. At the last follow-up, grade 1 xerostomia was reported in 38.9% of patients, with no grade 2 or higher xerostomia observed. One patient with lip cancer developed RTOG grade 3 myelopathy 13 months post-treatment, and one with tongue cancer developed grade 3 osteoradionecrosis (ORN) [28].

Long-term soft tissue toxicities included grade 1 superficial ulceration and fibrosis in 4 patients (22.2%). There were no cases of soft tissue necrosis (STN) or deep ulceration. No patients experienced any speech dysfunction, with swallowing function well-preserved, but 5 patients (27.7%) reported persistent sensitivity to spicy food. None of the patients developed ankyloglossia, trismus, or chronic pain. Sub-clinical hypothyroidism was detected in 8 (44.4%) cases.

Discussion

In this paper, we presented challenges faced in implementing an ISBT program for early-stage oral cancer in a newly commissioned comprehensive cancer center. The most significant challenge was initiating the program during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the preventive and safety protocols introduced during the pandemic allowed us to systematically review and troubleshoot the processes involved in ISBT implementation. While brachytherapy is primarily used for cervical cancer in India, its application in head and neck cancers accounts for less than 10% of the workload [29]. Therefore, to ensure the economic viability of a brachytherapy program, it is essential to expand its use to treat non-gynecological malignancies, such as head and neck, breast, soft tissue sarcoma, and prostate cancer, where there is strong evidence supporting its effectiveness. This approach could also enhance the utilization of teletherapy units more effectively by increasing the number of patients who receive EBRT, and significantly reduce wait times, especially in resource-constrained settings.

Challenges in implementing structured brachytherapy program in oral cancer

Feasibility of implementation of ISBT in the era of contemporary management of oral cancer

Establishing an ISBT program for oral cancer present challenges, particularly in patient selection, given the advancements in modern surgical techniques, which have placed surgery at the forefront of treatment [7, 30]. An Indian survey showed that head and neck brachytherapy accounted for only 10% of all brachytherapy procedures, primarily due to lack of expertise, complexities involved, and low remuneration rates [29]. High upfront cost of brachytherapy infrastructure and lower reimbursement are major reasons for its underutilization [16, 29]. However, when compared with EBRT, brachytherapy emerges as a time-efficient approach for both patients and physicians, benefiting in the long-run [31].

Technicality of ISBT in oral cancer

Case selection

We implemented several measures for selecting patients and documenting disease topography, including comprehensive clinical assessments (often performed under anesthesia) [22], baseline and serial clinical photographs [21, 22], placement of radio-opaque markers at tumor boundaries [21, 22], cross-sectional imaging for planning [23], and differential loading of catheters [32, 33]. Furthermore, detailed fixed-template clinical drawings and mapping of disease extent, especially for tongue cancer, were applied. This approach has shown to improve target coverage and prevention of geometrical misses [34]. After the initial few cases, a more cost-effective alternative of io-US was made available that precisely determine DOI. Based on surgical series, io-US has a better correlation with histopathological readings up to 10 mm, as compared with MRI in tongue cancers, which tends to overestimate the disease extent [35].

Quality of application

The quality of application is one of the most critical factor influencing the implant dosimetric parameters. Poor geometry can result in significant under- or overdosage in target regions or OARs, which optimization alone cannot fully correct [36]. A trained, collaborative team of physicians, physicists, and technologists is essential to maintain high standards in treatment planning and delivery. During the initial phase, careful execution and quality checks at multiple stages are crucial to prevent potential errors, as the processes are streamlined [37].

Intra-oral spacer

Higher incidence of ORN and STN have been reported in patients treated with single-plane implants and without using intra-oral spacers or shields [38]. Previously, various materials have been employed as spacers, including thermoplastic materials [39], silicone rubber [40], Lipowitz metal [41], and lead shields covered with siliconized rubber [42], which reduced doses by up to 70% [43]. Based on our experience, even though these spacers sufficiently reduced doses to the alveolar portion of the mandibular bone, they fell short in terms of reproducibility and patient comfort. With the advancement of expertise and infrastructure, we later fabricated customized acrylic shields, which provided improved reproducibility and optimal shielding.

Disease control in neck

In early-stage disease, one-third of clinically node-negative patients harbor risk of occult nodal metastases [25, 44], necessitating elective treatment [26, 27]. Primary brachytherapy combined with elective neck dissection, typically provides superior disease control [45]. However, ENI alongside brachytherapy, with surgical exploration reserved for salvage treatment, is also an effective approach, offering improved regional control [24]. Historically, most studies have used either 2-dimensional conventional [24, 39, 40, 46] or 3D-CRT techniques [33, 47]. The current study demonstrated VMAT feasibility, using its advantages in preserving swallowing function, reducing the incidence of xerostomia, and minimizing other soft tissue complications. Moreover, avoiding high doses to the laryngeal framework reduced post-EBRT edema, facilitating more comfortable endo-tracheal intubation during brachytherapy procedure.

Initial clinical experience

Comparison with historical series

Studies on low-dose-rate (LDR) brachytherapy (5-year LC, 85-90%) have shown outcomes comparable to that of surgical series (5-year LC, 77-85%), with the added benefit of preserving structure and function [45, 48, 49]. However, data on HDR brachytherapy are limited to a few series with varying doses and techniques (Table 4) [33, 42, 43, 47, 50-60]. A phase I-II study by Lau et al. found that LC with HDR brachytherapy (5-year LC, 53%) was lesser as compared with historical controls from the LDR era [51]. Conversely, Umeda et al. noted a slightly higher incidence of ORN that appeared to occur earlier in follow-up compared with LDR [61]. However, a phase 3 study [52] and few prospective studies [38-40, 54, 62, 63] published later reported that disease control, toxicity profile, and survival outcomes were almost identical to those of LDR.

Table 4

Selected series on HDR-ISBT in oral cancer

[i] RT – radiotherapy, LRC – loco-regional control, BM – buccal mucosa, FOM – floor of the mouth, ISBT – interstitial brachytherapy, fx. – fractions, LC – local control, RC – regional control, STN – soft tissue necrosis, ORN – osteoradionecrosis, CSS – cause-specific survival, LFFS – local failure-free survival, N.R. – not reported, EBRT – external beam radiotherapy, RFFS – regional failure-free survival

The optimal dose schedule for HDR brachytherapy has yet to be well-known, and the literature about this aspect is quite variable [64]. Akiyama et al. compared a lower dose schedule of 54 Gy in 9 fx. with a standard 60 Gy in 10 fx., and found no differences in terms of LC, RC, DFS, and OS [65]. In contrast, a series by Bhalavat et al. investigating a dose response relationship found that patients receiving higher biologically equivalent dose (BED) beyond 88.9 Gy or EQD2 beyond 74.1 Gy had significantly improved LC rates: from 27.5% to 87.5% in the brachytherapy alone group, and from 60% to 78.9% in the combined EBRT and brachytherapy group, highlighting the strong role of dose escalation in improving outcome [33]. In the present series, we used a median 74 Gy EQD2 dose in 8 patients (53.4%), receiving 77.5 Gy when EBRT was combined with ISBT. Initial disease burden, clinical response, and toxicities during EBRT as well as physician judgement were the factors that determined the final doses delivered. The recently published GEC-ESTRO guidelines emphasize the potential role of brachytherapy in carefully selected patients across diverse clinical scenarios, including radical, adjuvant, and re-irradiation treatment [64]. These guidelines also provide recommendations for standard doses and fractionation tailored to various sub-sites.

In the current study, one patient with lip primary, who did not achieve a complete response, was treated with ISBT alone, and dose prescription was 46.7 Gy EQD2. Dosimetric analysis revealed that dose received by 90% (D90%) and 98% (D98%) of CTV were 42.7% and 32.6%, respectively. Whereas homogeneity (DHI) and coverage indices (CI) were 0.69 and 0.36, respectively. Essentially, relatively poor implant geometry in addition to lower prescribed doses might result in the under coverage [64], leading to less than a complete response. Also, none of the patients with lip or buccal mucosa developed LRF. However, seven tongue cancer patients experienced LF at intervals ranging from 3 to 24 months, and three of these patients received a slightly lower EQD2 doses (73.5, 74.5, and 74.8 Gy); other dosimetric parameters did not reveal any significant differences. Moreover, studies have shown that T1 stage patients [46, 54, 61, 63], those with superficial and well-differentiated histology [38], and elderly patients [10, 63] have better prognoses. All these patients were having infiltrative type of lesion with moderate grade of differentiation, reflecting a slightly aggressive tumor biology, leading to disease progression.

Regional control by incorporating EBRT

Another crucial treatment-related factor influencing outcomes is the incorporation of EBRT, which involves balancing the risk of LRF. In a series by Bansal et al. involving 92 patients with oral cancers (67.4% treated with brachytherapy alone, and 32.6% with a combination of EBRT and brachytherapy), the 5-year LC for T1 stage was significantly higher in patients treated with brachytherapy alone compared with combined treatment group (81.7% vs. 62.5%; p = 0.04). For T2 stage, the combined treatment group had better 5-year RC (92.9% vs. 74.3%; p = N.S.) and disease-free survival (51.9% vs. 46.9%; p = N.S.) than the brachytherapy alone, although the differences were not statistically significant [47]. In the present study, all tongue cancer patients received ENI, and none of these patients had isolated RF. Two patients developed RF, but were associated with LF as well. Thus, an inadequate response at local site leading to LRF might be a contributing factor. As there was no significant toxicity and LF was the commonest pattern of relapse, this analysis points towards the need for intensification of the local dose through brachytherapy component. Furthermore, we used surgery as a salvage treatment for patients who either developed LRF or had residual disease post-ISBT. Among those who underwent surgery, disease control was achieved in all but one cases. Similar approaches were reported in the literature [39, 51, 54], resulting in comparable outcomes with those observed in our study.

Toxicity profile

Historically, long-term toxicities associated with head and neck ISBT have been in the range of 4-22% [33, 42, 43, 47, 50-60]. Apart from addition of EBRT to ISBT [55], various dosimetric parameters of implant have been associated with long-term complications [59, 66]. Potharaju et al. reported that V150 was significantly higher in patients who developed STN (7.89 ±1.2 cc vs. 6.52 ±0.99 cc; p = 0.005) and ORN (8.42 ±1.64 vs. 6.64 ±1.04; p = 0.002) [59]. Similarly, Ghadjar et al. found a statistically significant association between V100, V150, D50, and D90 for long-term toxicities [66]. García-Consuegra et al. found that patients receiving total physical doses > 61 Gy to maximally irradiated 2 cc of the mandible had a 20-fold increased risk of ORN [67]. In the present study, one patient (5.5%) who developed ORN was one of the earliest tongue cancer cases treated without the use of acrylic shield. Dosimetric parameters revealed that D90 and D98 covered 132% and 116% of CTV volume and V200%, V150%, and V100% of the implant were significantly higher (6.22 cc, 14.82 cc, and 31.05 cc, respectively), with a dose homogeneity index (DHI) of 0.52, whereas doses delivered to 0.1 cc (D0.1cc), 1 cc (D1cc), and 2 cc (D2cc) of the mandible were 134%, 99.3%, and 84.6% of the prescription dose. The total physical dose D2 cc for the mandible was 74.03 Gy. Additionally, one patient with upper lip primary who received EBRT developed grade 3 cervical myelopathy. Dosimetry showed that doses delivered to the spinal cord and brainstem were within the constraints (D0.1cc, D1cc, and D2cc of the spinal cord, and brainstem were 46.12 Gy and 43.6 Gy; 46 Gy and 34.6 Gy; and 46 Gy and 11 Gy, respectively), and setup errors within the tolerance limits [68]. Both the patients were managed conservatively and received hyperbaric oxygen therapy along with other supportive measures. In addition, moderate-severe (≥ grade 2) toxicities were not reported until the last follow-up.

Strengths of the study

The study highlighted various challenges encountered in implementing brachytherapy for non-gynecological malignancies, such as head and neck cancers, and presented cost-effective and streamlined solutions for addressing them. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first clinical experience using 60Co brachytherapy source for oral cancer. Also, regarding logistical advantages, dosimetric studies have shown that a small increase in dose observed along the source axis does not negatively impact outcome when adequate dose optimization is performed [69]. This is further strengthened by our clinical data. Additionally, the current work is the first study to employ an advanced EBRT technique, i.e., VMAT along with daily imaging, for controlling microscopic disease in the neck. These conformal techniques complement each other in achieving better outcomes. Moreover, the use of appropriate spacers and precise dose optimization helped maintaining acute and long-term toxicities within acceptable limits.

Limitations of present study

This preliminary single-institution experience in a small sub-group of patients emphasize the utility of ISBT in the era of modern radiotherapy, demonstrating modest clinical outcomes and providing a future roadmap for the adoption of brachytherapy in suitable cases. Even though the follow-up period in our study was relatively short, it was sufficient enough to gain insight into patterns of failure in this novel treatment approach, as most of the studies indicated 80-90% of recurrences manifesting within two years [33, 46, 54, 61, 70].

Nevertheless, the methodology detailed in the study, including proper case selection by a MDT discussion, use of intra-oral spacers, 60Co source offering logistical and financial advantages, and the use of VMAT technique, has the potential to improve the current landscape of oral cancer brachytherapy.

Conclusions

This research highlights an effective way of managing initial challenges in implementing brachytherapy of oral cancer in a new setup. The study further demonstrates the feasibility and effectiveness of 60Co-based HDR-ISBT in managing early-stage oral cancer, providing modest oncological outcomes with manageable toxicity profiles.