Purpose

Malignant liver tumors (MLT) can be classified into primary liver malignancies or metastatic lesions from other anatomical site [1]. Non-surgical curative local liver directed therapy (LDT) for MLT include radiofrequency ablation (RFA), microwave ablation, cryo-ablation, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), proton therapy, selective intra-arterial radiotherapy (SIRT), and high-dose-rate interstitial brachytherapy (HDR-IBT) [2]. For radiation modalities, such as SBRT and HDR-IBT, tumor control correlates with the total dose delivered to the target [3, 4]. Radiation modalities, including SBRT, proton therapy, and HDR-IBT, are currently gaining momentum as the preferred option in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) due to the inherent radiosensitivity of this tumor [5]. While SBRT is non-invasive, it comes with the issue of motion management and larger PTV margin to account for the respiratory motion [6-8]. High-dose-rate IBT, on the other hand, has a better dose conformity and less issues with motion management, because the implanted applicators move with respiration [3, 6]. Moreover, HDR-IBT has a distinct advantage in treatment of sub-diaphragmatic tumors compared with thermal ablation methods, such as RFA and microwave ablation, due to the complexity of these procedures and the risk of thermal damage to the diaphragm and lung [9, 10].

In liver HDR-IBT, for tumors adjacent to the diaphragm, radiation exposure to the diaphragm and lung tissue cannot be prevented. Based on SBRT experience, fractionated SBRT doses with maximum dose to the diaphragm (Dmax < 56 Gy), are well-tolerated [11]. However, liver HDR-IBT is usually delivered with single-fraction, and in sub-diaphragmatic tumors, single-fraction dose (Dmax) to the diaphragm can be as high as 100 Gy [12]. Furthermore, some patients may have repeated treatments with HDR-IBT to the same area of interest (AOI) in the diaphragm and lung.

There is a paucity of data on diaphragm tolerance for ablative doses of radiation either in SBRT or HDR-IBT setting as well as for lung tissue tolerance for single-fraction extreme high-dose small volume exposure. This manuscript retrospectively reports the diaphragm and lung dosimetric data and toxicity of 27 patients with 43 sub-diaphragmatic MLTs treated with liver HDR-IBT at our center from September 2018 till June 2023. This report can be an important guidance to radiation oncologist and medical physicist specializing in SBRT and HDR-IBT in determining the dose tolerance of diaphragm and small volume of normal lung tissue. This study received institutional human ethics approval by Jawatankuasa Etika Penyelidikan Manusia USM (JEPeM).

Material and methods

Patient characteristics

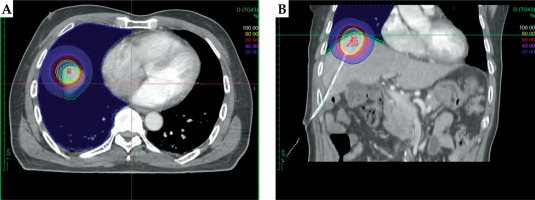

Computed tomography (CT)-based liver HDR-IBT using Oncentra Brachy treatment planning system (TPS) plans of patients with MLT between September 2018 and June 2023 were reviewed to identify patients, whose diaphragm and lung tissue were within 100% prescription isodose (Figure 1). Patients with less than 6 months of follow-up were excluded from the study. Patient demographics and toxicity data were retrieved from the hospital electronic records. Liver HDR-IBT procedure and treatment protocol is available from previous publication by Appalanaido et al. [12].

OARs delineation and dosimetric data collection

The diaphragm was contoured slice-by-slice in 2 mm thick axial planning CT images, using 0.2 cm diameter pearl tool in Oncentra Brachy TPS version 4.3 (Nucletron, Elekta AB, Stockholm, Sweden), which corresponded to anatomical diaphragm thickness and lung tissue within the scan range, and was contoured in lung window (Figure 1). Prescribed dose (PD), tumor volume, diaphragm and lung dose volume parameters [maximum point dose (Dmax), minimum dose to 0.2 cc, 0.5 cc, and 1 cc (D0.2cc, D0.5cc, D1cc), volumes receiving 30 Gy and 50 Gy (V30Gy and V50Gy)], and total number of HDR-IBT treatments, were retrospectively retrieved from Oncentra Brachy TPS with TG-43 algorithm. In two patients who underwent repeated HDR-IBT in the same region of diaphragm and lung, cumulative doses for both OARs at Dmax, D0.2cc, D0.5cc, and D1cc were estimated by fusing the treatment plans.

Statistical analysis of dosimetric parameters for OARs using SPSS

Statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) software version 25.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA) was applied for statistical analysis of the diaphragm and lung dosimetry. Selection of statistical tests was based on Shapiro-Wilk test outcomes, with a pre-defined significance threshold of p < 0.05. Spearman’s correlation and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to access the relationship between GTV dimension and prescribed dose against both OARs exposure, respectively. Dosimetric analysis of the diaphragm and lung were presented as descriptive statistics.

Follow-up and toxicity

The standard follow-up schedule for liver brachytherapy patients at our center is 2 weeks for initial post-treatment follow-up with blood test, and a repeat blood test at 6 weeks post-treatment at the liver HDR-IBT clinic. Radiological investigations are performed at 2 monthly interval for post-treatment assessment, and for up to 6 months if complete resolution of the treated tumor is not observed in the initial scans. Toxicity data, including patient-reported symptoms of right shoulder pain, right hypochondriac pain, and cough for the 27 patients were retrospectively collected from patients’ electronic medical records. Diaphragm pain was scored retrospectively using the common toxicity criteria for adverse events, version 5.0 (CTCAE 5.0) assumption of mild pain corresponding to grade 1.

Results

Patient demographics and treatment characteristics

Between September 2018 and June 2023, twenty-seven patients with 43 sub-diaphragmatic MLTs underwent liver HDR-IBT. The median tumor and diaphragm volumes were 5.88 cc (range, 0.34-755.47 cc) and 56.4 cc (range, 29-83.2 cc). The patient and treatment characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Patients demographics and treatment characteristics (n = 27)

Dose volume parameters

Spearman’s rank correlation and Kruskal-Wallis tests did not show statistically significant relationship between tumor dimension and prescribed dose against diaphragm and lung exposures, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Spearman’s rank correlation and Kruskal-Wallis tests for tumor dimension and prescribed dose against diaphragm and lung exposure

The dose volume data and its 2 Gy equivalent dose (EQD2) of the 43 and 36 MLTs with 100% prescribed isodose within the diaphragm and lung, respectively, are shown in Table 3A. The median values were used, as the data were non-parametric. For the 2 patients who underwent repeated HDR-IBT, the cumulative OARs doses and EQD2 at Dmax, D0.2cc, D0.5cc, and D1cc are presented in Table 3B.

Table 3

Organs at risk (OARs; diaphragm and lung tissue) exposure from A) single and B) repeated HDR-IBT session

Clinical outcomes

With a median follow-up of 23 months, ranging from 6 to 57 months, 23 of the 27 patients are still alive. Two patients, who had diaphragm Dmax of 395 and 396 Gy, experienced persistent grade 1 (as per CTCAE v. 5.0) right shoulder pain after 6 and 9 months of HDR-IBT, most likely due to diaphragm injury. No symptoms related to lung injury, such as cough and shortness of breath, were reported by any patient.

Discussion

While conventionally fractionated and hypofractionated radiotherapy dose tolerance to most of OARs in the abdomen and thorax are well-defined in the literature, there is a paucity of data regarding the real diaphragm radiation tolerance [13]. Since many patients with sub-diaphragmatic MLTs are considered not suitable for thermal ablation methods, they are treated with liver HDR-IBT at our center. We noticed that the diaphragm and small volume of lung tissue receive extremely high doses of radiation using liver HDR-IBT, and hence this retrospective study was conducted to estimate the radiation tolerance for the diaphragm and small volume of lung tissue. Sioshansi et al. reported on two patients who underwent SBRT with a median PD of 50 Gy (range, 30-54 Gy, 3-5 fractions) and received Dmax of 61.6 Gy and 56.8 Gy to the diaphragm; they experienced diaphragm necrosis and right scapular pain. The authors suggested radiation dose tolerance to the diaphragm as V30Gy < 31.8 cc and V50Gy < 10 cc [11, 14].

In the current study, the Dmax of 302 Gy (range, 54-396 Gy) has far exceeded the reported Dmax in the 2 patients with diaphragm necrosis, as reported by Sioshansi et al. Furthermore, in 26 out of the 27 patients in our study, the diaphragm Dmax exceeded 62 Gy. However, the suggested V30Gy and V50Gy constraints were well achieved (V30Gy and V50Gy of 1.1 cc and 0.2 cc) due to the physical property of HDR-IBT as compared with external beam radiotherapy (SBRT) [7, 8, 11, 14]. However, it should be noted that liver HDR-IBT is delivered in a single-fraction unlike most of SBRT regimens, where the dose is delivered over 3 to 5 fractions [4, 11, 14]. In the 2 patients who underwent repeated HDR-IBT with radiation exposure to the same region of the diaphragm, the cumulative Dmax was 698 Gy and 792 Gy. In perspective, this translates into median EQD2 of 50,023 and 63,202 Gy for single-fraction liver HDR-IBT compared with EQD2 of 130 Gy from SBRT, with a prescribed dose of 50 Gy in 5 fractions using an alpha/beta (α/β) ratio of 3 for normal tissue, as suggested by Scheenstra et al. [15]. At a median follow-up of 23 months, only 2 out of the 27 patients (7.4%) had mild (grade 1) right shoulder pain (most likely referred to pain from the diaphragm) despite the high-dose exposure, possibly due to the small volume involved and high radiation-tolerance of the diaphragm [16]. Moreover, the statistical analysis showed no association between tumor dimension or PD with diaphragm and lung radiation exposure.

Given that the V30Gy and V50Gy of the diaphragm tend to be very low in liver HDR-IBT, we suggest additional dosimetric parameters, such as D0.2cc, D0.5cc, and D1cc on top of Dmax for the purpose of reporting and future research. In this study, the maximum point dose was significantly higher than D0.2cc, D0.5cc, and D1cc due to the heterogenous dose distribution in HDR-IBT [8, 12]. Our study also showed there is no statistically significant association between tumor dimension or PD with diaphragm and lung radiation exposure.

The irradiated lung volume from liver HDR-IBT is usually at the right lung base adjacent to the diaphragm that is further away from the central lung “no-fly zone”. While there is abundant data in the literature on lung SBRT and the associated toxicity it is not known if the same can be extrapolated to HDR-IBT. Despite the fact that only a small volume is irradiated, dose heterogeneity inside HDR-IBT treatment volume is large, unlike more homogenous SBRT [7, 8, 12]. It is not known if these extreme high doses as seen in the lung can result in clinically significant lung injury, such as pneumothorax. As seen in this study, the median Dmax, D0.2cc, D0.5cc, and D1cc of 90 Gy, 55 Gy, 44 Gy, and 34 Gy, respectively; the doses were well-tolerated and no patient developed clinical pneumothorax or symptoms of lung injury symptoms at a median follow-up of 23 months. The small volume of high-dose region and being in the periphery of the lung field, may explain this low toxicity.

Even though we calculated EQD2 for single-fraction high-dose HDR-IBT for comparison with existing fractionated radiotherapy protocols, it has its limitation. The drawbacks related to EQD2 in general include its purposely designed for conventional EBRT treatment instead of single-fraction high-dose HDR-IBT and generally it disregards cell repair, low dosage hypersensitivity, and linearity at high-dose [17]. Furthermore, it requires precise α/β ratio of OAR for calculation [15]. Another issue in this study is that the TG-43 algorithm used in Oncentra Brachy TPS overestimates the dose to OAR due to the absence of inhomogeneity correction [18, 19].

From this small retrospective series, it can be concluded that small volume of the diaphragm and lung tissue can tolerate point doses, which are 5 times more than what is used in SBRT of the liver or lung, despite being delivered in single-fraction. We would like to suggest a standardized reporting for diaphragm and lung in liver HDR-IBT with Dmax, D0.2cc, D0.5cc, and D1cc for the diaphragm and lung tissue. In future, these data can also be used in lung HDR-IBT, if brachytherapy indication is further expanded.

Conclusions

This is the first publication in the literature that considered the dia- phragm and lung tissue dose volume parameters in liver HDR-IBT and its clinical toxicity. Small volume of the diaphragm and lung tissue tolerated extreme high doses of radiation (in the range of 5 times of that used in SBRT), without significant morbidity. Current constraints used for these organs maybe too conservative. A standardized reporting is needed for future liver HDR-IBT studies for diaphragm and lung tissue as OARs. Data from this study can also be used in future for expanded indications of brachytherapy, such of trans-thoracic CT-guided lung brachytherapy.