Introduction

Retrotransposable elements (RTE) can lead to insertional mutagenesis, alternative splicing, genome instability, aberrant transcription, and DNA damage [1]. Retrotransposable element-derived sequences contain two-thirds of a human genome [2], a considerable part of which was active millions of years ago and is no longer intact. LINE-1 (L1) is a human RTE potential of autonomous retrotransposition. LINE-1 with germline activity is a key source of human structural polymorphisms [3]. Activation of retrotransposable elements is increasingly evident in several types of cancer, the adult brain, and in aging [4–7]. Notably, cellular defences include small RNA pathways that target transcripts, heterochromatinisation of elements, and antiviral innate immunity mechanisms.

This review highlights that inhibition of retrotransposon activity and age-associated inflammation can be used to treat age-related diseases.

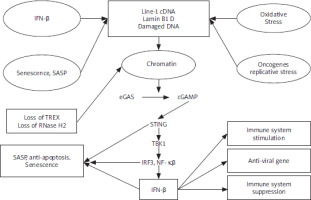

Activation of LINE-1 and type-I interferon

De Cecco et al. [8] reported that L1 transcription is triggered exponentially in the replicative senescence of the human fibroblasts, thus increasing 4–5-fold by 16 weeks following the cessation of the proliferation, which is referred to as late senescence. To analyse evolutionarily L1 elements (L1HS-L1PA5), various reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) primer pairs have been designed. Throughout the entire element, L1 poly(A)+ RNA levels increased 4–5-fold in late replicative senescent cells in a sense but not in an antisense direction. The 224 elements showed by Sanger sequencing of the long-range RT-PCR amplicons, which dispersed all over the genome, of which one-third (75, 33.5%) were L1HS, and of which 19 (25.3%, 8.5% of total) were intact (annotated as free of open reading frame [ORF]-inactivating mutations). Thus, these findings indicate that most of the L1 transcripts upregulated in the senescent cells initiate at and/or near a 5′ untranslated region (UTR) performed by 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends by the same primers. Type-I interferon (IFN-I) response can be stimulated by L1 elements [9]. In late senescent cells, α-family interferons (IFNA gene cluster on chromosome 9), IFNA, as well as IFNB1 can be increased to high levels [8]. Through the early DNA damage-response phase, cellular senescence proceeds, which is followed by a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) response [10]. Notably, upregulation of the L1, as well as IFN-I response, characterises the third and later phase, which has not been confirmed because the majority of findings have focused on the earlier times [8]. Type-I interferon and SASP responses are temporally distinct, which is proven by whole transcriptome RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis. These findings suggest L1 activation with late phase and IFN-I with induction by stress-induced premature senescence (SIPS) as well as oncogene-induced senescence (OIS). In terms of the contribution to genetic disease as well as aging, transposition can alter the genome at deletion or integration sites [11, 12]. It has been suggested that LINE-1 transcription and transposition are activated by senescence-related chromatin reorganisation (lamin B-mediated) [13]. Transposition has side effects, such as DNA damage and DDR signalling, that drive cell senescence and aging [13–15]. In senescent mesenchymal stem cells, DNA repair foci are over-represented at Alu elements, and the knockdown of Alu transcripts can somewhat reverse senescence [16]. Our previous finding supports the present finding regarding molecular mechanisms of Alu and LINE-1 interspersed repetitive sequences in aging [17]. Type-I interferon-mediated cell senescence is involved in the identification of LINE-1 DNA-RNA hybrids. Human fibroblasts upregulate LINE-1 RNA transcripts by spontaneous-, oncogene-, or oxidative stress-induced senescence. The induced IFN-α/β family genes in a reverse transcriptase-dependent and STING-dependent manner [18]. The upregulation of LINE-1 ascribes to loss of LINE-1 repressor RB1, loss of exonuclease TREX, and FOXA1 upregulation, LINE-1 activator that binds 5’ UTR. The expression of some SASP components (CCL-2, IL-6, MMP-3) but not IL-1β are suppressed when IFN expression is abolished. Temporal switches that determine senescence response, both LINE-1 and IFN-expression, occur in a previously overlooked “late-senescent phase” following phases, whereas DNA damage signalling and SASP induction occur. The treatment of aged mice elevates LINE-1 transcripts in some tissues with a reverse transcriptase inhibitor and decreases expressions of IFN-I and IFN-I target genes, as well as SASP. This reverses some age-related pathologies, such as skeletal muscle atrophy and macrophage infiltration. These findings indicate that the LINE-1 cDNA STING/IFN-I pathway maintains several aspects of cell senescence by the STING/IFN-I pathway. Considering that nuclear cGAS localizes to LINE-1 elements preferentially, it is possible that cGAS plays a key role as a “transposition sensor” in addition to its other roles [19]. The complex interplay among cell senescence, DNA damage signalling, and IFN-I are presented (Figure 1).

Mechanism of LINE-1

During senescence, 3 factors, including FOXA1, RB1, and TREX1, have been investigated to determine surveillance fails [8]. The 3′ exonuclease, including TREX1, destroys the invasion of foreign DNA, and its loss is associated with an accumulation of cytoplasmic L1 cDNA [20]. In senescent cells, TREX1 expression reduces [8]. RB1 binds to repetitive elements, including L1 elements, and improves heterochromatinization of these elements [21]. In senescent cells, RB1 expression declines, while expression of such RB family members, including RBL1 as well as RBL2, remains without changes [8]. RB1 enrichment in 5′ UTR of L1 elements is evident in proliferating cells, declines during early senescence, and is undetectable at later times. In these regions, this coincides with a decline in histone 3 Lys9 trimethylation (H3K9me3) as well as H3K27me3 marks. ENCODE chromatin-immunoprecipitation, which is followed by a sequencing (ChIP-seq) database, indicates pioneering transcription factor FOXA1 binding to this region in various cell lines to detect factors interaction with L1 5′ UTR [8]. In senescent cells [22], FOXA1 can be upregulated and bound to a central region of L1 5′ UTR. FOXA1-binding site with deletion decreases sense as well as antisense transcription from L1 5′ UTR by transcriptional reporters [8, 23]. Senescent cells show a misregulation of all these 3 factors, which can lead to L1 activation via 3 mechanisms: (1) loss of RB1 via heterochromatin repression, (2) gain of FOXA1 via activation of L1 promoter, and (3) loss of TREX1 via compromising removal of L1 cDNA. Lentiviral vectors can be used to determine the effect of altering FOXA1, RB1, and TREX1 expression in senescent cells [8]. The increase in expression of L1, IFNB1, and IFNA in senescent cells is suppressed by RB1 ectopic expression, while RB1 knockdown increases their expression. Notably, overexpression of RB1 maintains its occupancy of L1 5′ UTR. FOXA1 overexpression increases the expression of L1, IFNB1, and IFNA, while FOXA1 knockdown reduces its binding to L1 5′ UTR and decreases the expression of L1, IFNB1, and IFNA. Manipulating TREX1 can lead to similar findings. These findings indicate a tangible effect of these factors on the basis of regulation of L1 as well as IFN-I response in senescent cells. In growing early passage cells, single interventions targeting these factors cause small changes in L1 expression. Double interventions show similar minor effects on IFN-I levels. These alterations remain limited in healthy, proliferating cells. Such effects are statistically important; they are overshadowed by the triple intervention (3×) of TREX1 as well as RB1 knockdowns with FOXA1 overexpression and lead to considerable upregulation of L1 as well as IFN-I expression [8]. Thus, to unleash L1, all 3 effectors can be compromised in normal healthy cells. In the lead-up to a retrotransposition event, it is believed that ORF2p nicks chromosomal DNA randomly at hundreds of locations [24]. The somatic effects of L1 nicking and retrotransposition on DNA integrity are not well understood. Thus, considering their “well-documented deleterious effects, the persistence of L1 activity remains a puzzle” [25]. When L1 activity leads to genetic disease, whether through an insertion event or a deleterious homologous recombination event is a major topic of concern about L1 expression. It is hypothesised that accumulation of L1 retrotransposon-mediated DNA damage with chronological age contributes to a decrease in progenitor population-regenerative capacity and physiological aging of tissues. LINE-1 expression can be seen not just in germ lines but in some somatic cells, including endothelial cells, and in somatic tumours as well as tumour cell lines [26, 27]. Even at a modest level, L1 activity can contribute to DNA damage, genomic instability, elevated replicative stress, and cellular senescence if it is supported to continue for decades. A subpopulation of adult stem cells that respond to tissue regeneration signals would be most susceptible to L1-induced damage.

Mechanistic basis of LINE-1

LINE-1 reverse transcriptase activity is inhibited by nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), which have been suggested to treat human immunodeficiency virus [28]. Notably, short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) target L1, 2 of which reduce transcript levels by ranging 40–50% and 70–90% in deeply senescent as well as 3× cells, respectively [8]. In deeply senescent cells, the amount of ORF1 protein decreases correspondingly. These findings indicate that the retrotransposition of recombinant L1 reporter constructs is reduced by shRNAs. TREX1 devoid cells that show cytoplasmic L1 DNA, which can be suppressed with NRTIs from accumulation [20]. Longer-term labelling indicates that DNA species are cytoplasmic and enriched for L1 sequences because the lack of BrdU incorporation indicates a canonical feature of senescent cells. shRNA or NRTI lamivudine (3TC) to L1 can block cytoplasmic L1 DNA with synthesis. In senescent cells, cytoplasmic signals are identified by antibodies to DNA-RNA hybrids, which colocalize with ORF1 protein and then turn into single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) signals following RNase digestion. In senescent cells, analysis of BrdU-labelled L1 sequences indicates that they are localised all over an L1 element. This increase in senescent cells is blocked by 3TC ranging from 7.5 to 10 µM and suppresses the activity of L1 retrotransposition reporter. In late senescent and 3× cells, treatment of cells with 3TC or knockdown of L1 with shRNA decreases interferon levels and IFN-I response [8]. Notably, the highly efficient of 4 NRTI tests is 3TC ranging from 7.5 to 10 µM, which inhibits IFN-I response. To inhibit human L1 reverse transcriptase, the efficacy of NRTIs is consistent with their relative ability [28]. In forms of senescence, such as SIPS as well as OIS, the 3TC antagonises the IFN-I response. Passage cells from the proliferative phase to deep senescence should be considered in the presence of 3TC [8]. Notably, 3TC indicates no effect on the time of entry to senescence, early SASP response (IL-1β upregulation), or induction of p16 or p21. The magnitude of later SASP response (induction of MMP-3, CCL-2, IL-6) is decreasing. In late senescent cells, L1 shRNA treatment reduces the expression of MMP-3 as well as IL-6. Late in onset, L1 activation and ensuing IFN-I response lead to mature SASP as well as pro-inflammatory phenotype of senescent cells. LINE-1 transcript levels cannot be affected by 3TC, indicating L1 cDNA-activated IFN-I response. These findings indicate that the knockdown of cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway components STING and/or cGAS [29] inhibits IFN-I response in late-senescent as well as 3× cells and downregulates SASP response in late-senescent cells. Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors alkyl-modified at 5′ ribose position cannot be phosphorylated and thus cannot suppress reverse transcriptase enzymes, indicating intrinsic anti-inflammatory activity via inhibition of P2X7-mediated mechanisms, which triggers the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. At 10 µM or 100 µM, tri-methoxy-3TC (Kamuvudine-9, K-9) cannot suppress IFN-I response in late senescent and/or 3× cells. Notably, reverse transcriptase inhibition is required for 3TC to show an effect on the IFN-I pathway. K-9 indicates an inhibitory effect on inflammatory markers at high concentrations (100 µM), which is consistent with earlier stated studies [30]. CRISPR-Cas9 can be used to inactivate IFN-α as well as IFN-β receptor genes (IFNAR1, IFNAR2) for testing the role of interferon signalling in SASP [8]. Our previous finding supports the present finding regarding CRISPR-Cas9 in aging and neurodegenerative diseases [31]. In early passage as well as deep senescent cells, effective ablation of IFN-I signalling can be obtained. Notably, loss of interferon signalling antagonises late (MMP-3, CCL-2, IL-6) but not early (IL-1β) SASP markers in SIPS and replicative forms of senescence. These findings indicate that IFN-I signalling helps senescent cells establish a full as well as mature SASP response. These findings extend an RNA-seq transcriptomic analysis. Because of truncations and inactivating mutations, approximately 500,000 copies of L1 in the human genome lack the ability to transpose on their own. There are still approximately 80 to 100 fully functional copies of family L1PA1 that can transcribe, translate, replicate, and retrotranspose by RNA intermediate [32]. About 1 in 30 individuals are believed to have a novel L1 insertion. However, the majority of these insertions are obviously harmless [33]; insertions that occur in exons or significant regulatory regions are linked to genetic disorders. The insertion of truncated L1 5’ promoter regions into DNA next to existing genes can contribute to the expression of neighbouring genes with changes, which is significant because of their bidirectional promoter activity. In human cells, in vitro expression of L1-derived ORF2 protein results in apoptosis, DNA damage, and cellular senescence because of its intrinsic endonuclease activity [24]. Forced overexpression of L1 activity from multicopy plasmids contributes to a high level of DSBs, leading to H2AX foci [34], which is a characteristic of senescent cells [35]. Similarly, L1 with chromosomal inversions, insertions, exon deletions, and flanking sequence comobilisation shows direct proof of genetic instability due to L1 with episomal expression, which is followed by selection, capture, and sequencing of genomic L1 integrants [36, 37]. Just a small percentage of nicks lead to sustained damage or retrotransposition because of incredibly developed and effective repair mechanisms. There is always a chance that a repair will be imperfect, leading to competition between damage and repair [38]. This would lead to point mutations, rearrangements, chromatin damage, and replicative stress. It is hypothesised that accumulation of these DNA breaks and misrepairs with age activate p16/pRB and p53 cellular senescence pathways in cells that are challenged in proliferation. It is speculated that chronic low-level L1 activity contributes to the formation of human extrachromosomal inter-Alu DNA circles, which is a characteristic of aged cells [39].

LINE-1 in humans and mice

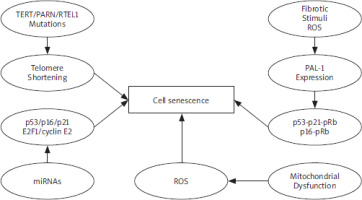

Open reading frame 1 antibody has been used to identify activation of the L1 expression during cancers in humans [4]. In senescent and 3× cells, widespread ORF1 expression is indicated by the same reagent [8]. The 10.7% of dermal fibroblasts in skin biopsies of aged human individuals tested positive for a senescence marker, including p16, which corresponds to a range in aging primates [40]. For ORF1 (10.3%), p16-positive dermal fibroblasts can be positive. Considering the absence of p16 expression, ORF1 cannot be observed. In the tissue microenvironment, the presence of phosphorylated STAT1 is parallel with interferon signalling at a single-cell level [41]. These findings indicate L1 activation by a fraction of senescent cells in normal human individuals, indicating that these types of events accumulate as senescence progresses. Key molecular mechanisms that drive cellular senescence, with a focus on LINE-1- mediated pathways to age-associated inflammation. These pathways, including cytoplasmic cDNA accumulation, STING/IFN-I activation, and SASP development, are modulated by LINE-1 reverse transcriptase activity and present targets for therapeutic intervention (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Mechanism in cell senescence. Several stress conditions indicate cell senescence, such as oxidative stress and DNA damage. These signalling pathways lead to cell senescence under distinct conditions PAI-1 – plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, PARN– polyadenylation-specific ribonuclease deadenylation nuclease, ROS – reactive oxygen species, RTEL1 – regulator of telomere elongation helicase-1 TERT – telomerase reverse transcriptase

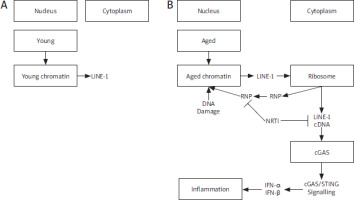

Such findings indicate the upregulation of L1 mRNA with age in various tissues in mouse examination [8]. Our previous study supports the present finding regarding mRNA expression in a mouse model of aging and neurodegenerative diseases, offering potential therapeutic effects [42]. LINE-1 RNA sequences sense strands displayed across an element; all 3 active L1 families are observable. Notably, the frequency of L1 ORF1-positive cells increases with age in tissues at the protein level. Thus, regions of ORF1 staining colocalise with the activity of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal). In tissues of old (26 months) mice, various IFN-I response genes (OAS1, IFNA, IRF7), pro-inflammatory and SASP markers (IL-6, MMP-3, PAI-1 [SERPINE1]), are upregulated. Considering an experimentally induced model of cellular senescence (young mice subjected to sublethal irradiation), the findings indicate an increase in L1 expression and IFN-I response genes (OAS1, IFNA). 3TC (can be administered in water and at human therapeutic doses) treatment for 26-month-old mice downregulates IFN-I response and alleviates the SASP pro-inflammatory state in a broad and significant way [8]. However, L1 and p16 (CDKN2A) mRNA expression downregulates but cannot achieve statistically significant results in most cases. Type-I interferon or SASP responses cannot be affected by K-9. Senescent cells express SASP markers while ORF1-expressing cells activate IFN-I signalling based on immunofluorescence analysis of tissue sections. The 3TC treatment reduces IFN-I as well as SASP responses but does not include the presence of senescent cells or L1 expression, in contrast to senolytic treatments, which can remove senescent cells from tissues, thus NRTIs can be classified as senostatic agents [43, 44]. Natural aging causes decreased adipogenesis [45] and thermogenesis [46], while 2 weeks of treatment with 3TC increases both in old mice. In opposing a number of aging phenotypes, including skeletal muscle atrophy [47], glomerulosclerosis of the kidney [48], and macrophage infiltration of tissues (a characteristic of chronic inflammation [45, 49]), thus longer-term treatments (20–26 months) can be successful. Age-associated inflammation is presented (Figure 3). After treatment with 3TC for 2 weeks, macrophage infiltration of white adipose tissue is effective and returns to youthful (5-month) levels. The role of transposable elements that have colonised the mammalian genome has been one of the most puzzling findings in aging systems. Most of these elements cannot replicate outside of the host cell, but they can still replicate their DNA within the host and pose a threat to the host genome. LINE-1 class of retrotransposons is successful and can be found in every mammalian genome with a ubiquitous feature, accounting for about 20% of DNA in mice and humans [50, 51]. This 6 kb retrotransposon has all the components for retrotransposition and can replicate itself as well as other retroelements that rely on L1-encoded proteins for retrotransposition: ORF1 is a nucleic acid chaperone, and ORF2 is endonuclease as well as reverse transcriptase [3, 52, 53]. LINE-1 activity has been associated with DNA damage and mutagenesis because of the need for DNA breakage and insertion for replication and expansion within a host genome [34, 36, 54]. LINE-1 activity in somatic tissues leads to many age-associated diseases, such as cancer and neurodegeneration, and studies on L1 have emphasised their activity in the germline [3, 54–56]. In light of the damage that L1 can cause, host genomes have developed several molecular mechanisms for silencing these parasitic elements [57, 58]. These mechanisms lose effectiveness with aging, which leads to L1 derepression [6, 7, 59]. Heterochromatin, which restricts the activity of these elements and can contribute to inflammation via innate immune response, appears to be redistributed and reorganised, facilitating this derepression [7, 20, 60, 61]. Regardless of evidence that suggests the upregulation in L1 expression is a characteristic of aging, it remains unclear whether inhibiting L1 activity has any effect on delaying the onset of age-related pathologies. In 2024, Shah et al. demonstrated short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs), a class of retrotransposons implicated in aging and age-related diseases, including neurodegeneration, cardiovascular disorders, and cancer. They explored their mechanistic roles in cellular dysfunction and highlights emerging SINE-targeted therapies – particularly antisense RNA – as potential anti-aging interventions, offering a roadmap for translating retrotransposon biology into clinical strategies for healthy aging [62].

Figure 3

Age-associated inflammation. LINE-1 retrotransposon elements derepress in aging (A), accumulation of cytoplasmic LINE-1 cDNA induces type-I interferon response by the cGAS DNA sensing pathway and leads to age-associated inflammation. Inhibition of L1 replication improves health and lifespan. RNP, Ribonucleoprotein (B)

Limitations

A phenotype that includes activation of the endogenous L1 elements and ensuing activation of IFN-I response indicated by naturally occurring senescent cells in tissues. As the senescence response progresses, this phenotype seems to be a vital but still underappreciated component of SASP. Senescence changes the expression of 3 regulators, including TREX1, RB1, and FOXA1, and these changes are effective and required for the transcriptional activation of L1 elements [8]. It is important to keep these types of elements repressed in somatic cells because various surveillance mechanisms should be overcome to unleash L1. The present review predicts that mechanisms of endogenous RTE activation and failure points need to be investigated in future studies.

Future perspectives

During aging and cellular senescence, the interferon- stimulatory DNA pathway can be used to activate innate immune signalling in response to L1 activation. Cytoplasmic DNA can originate from various sources, including cytoplasmic chromatin fragments from damaged nuclei [63] and/or mitochondrial DNA from stressed mitochondria [64]. This review suggests that L1 cDNA is an effective IFN-I inducer in senescent cells. Treatment with NRTI antagonises the IFN-I response and reduces age-related chronic inflammation in multiple tissues. Inflammaging and/or sterile inflammation is an important hallmark of aging and a contributor to several age-associated diseases [65, 66].