Purpose

Chemoradiotherapy is the standard treatment for locally advanced cervical cancer, typically comprising 25 fractions of external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) to a cumulative dose of 45 Gray (Gy) administered concurrently with platinum-based chemotherapy, followed by 3 or 4 fractions of high-dose rate (HDR) brachytherapy [1, 2].

Women with cervical cancer are at risk of developing venous thromboembolic event (VTE) [3]. One of the factors contributing to this increased risk of VTE development is the use of platinum-based chemotherapy, which may induce vascular toxicity [4]. Moreover, pelvic irradiation and immobilization during brachytherapy may increase the risk of VTE occurrence [5, 6].

In this case series, we reported three female patients diagnosed with near-fatal saddle pulmonary embolisms shortly after receiving intracavitary high-dose-rate (HDR) brachytherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. Patients’ consent was obtained. The summary of the three cases is provided in Table 1.

Table 1

Summary table of the three presented cases

Case summaries

Summary of case 1

A 35-year-old, non-smoking woman (BMI, 28 kg/m2) without comorbidities, with a FIGO stage IIIC1 (radiological T2bN1M0) squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix, received 45 Gy EBRT and 5 cycles of cisplatin (40 mg/m2). Subsequently, she underwent HDR brachytherapy with an immobilization period of 27 hours. High-dose thromboprophylaxis was prescribed during hospitalization.

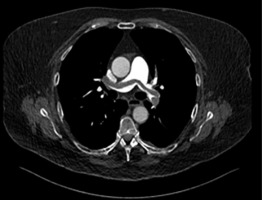

Approximately two hours after applicator’s removal, the patient collapsed, presenting with hypotension (60/40 mmHg), hypoxemia (oxygen saturation, 87%), and tachycardia (130 bpm). Despite supporting therapy with oxygen and a single-dose of dalteparin 15,000 IU, the patient deteriorated and developed a cardiac arrest, after which resuscitation was initiated. Emergency CT pulmonary angiography revealed a massive saddle pulmonary embolism in both main branches of the pulmonary artery as well as filling defects in the segmental and subsegmental branches (Figure 1A). Additionally, there was subdiaphragmatic free fluid around the liver (Figure 1B). Due to the risk of epidural hematoma and intra-abdominal bleeding with an epidural catheter in situ, low-dose alteplase was initiated (two single doses of 10 mg).

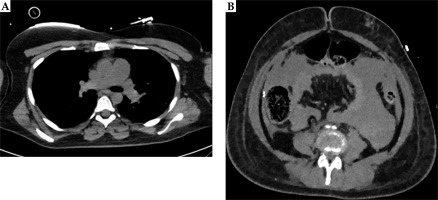

Fig. 1

A) CT angiography without contrast showing saddle pulmonary embolism (case 1). B) Abdominal CT angiography showing free fluid (case 1)

Ten hours after the collapse, the patient became hypotensive again with abdominal distension, suggesting hypovolemic shock due to intra-abdominal hemorrhage post-resuscitation. CT angiography revealed active bleeding from the liver parenchyma. Selective coil radio-embolization was successfully performed on the right and left hepatic arteries.

The following day, the patient developed new bleeding from the superior mesenteric artery and abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS). Decompressive laparotomy was performed with packing of the liver. A re-laparotomy due to persistent bleeding was necessary, and subcutaneous bleeding foci were treated. The patient remained hemodynamically stable and underwent abdominal closure 48 hours later. She was discharged home 18 days after the resuscitation. The patient showed a complete oncological remission during a response evaluation at three months, and recovered well from the embolism and subsequent surgeries. Currently, the remission continues to progress.

Summary of case 2

A 66-year-old, non-smoking obese woman (BMI, 36 kg/m2), with a history of diverticulitis and FIGO stage IIIC1 (radiological T2bN1M0) squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix, was treated with 45 Gy EBRT and 5 cycles of cisplatin (40 mg/m2). Subsequently, the patient underwent HDR brachytherapy, with an immobilization period of 28 hours. During her hospitalization, high-dose thromboprophylaxis was administered.

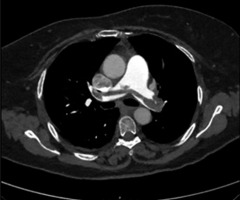

Approximately two hours after applicator removal, the patient developed a fever (38.7°C temperature) and hypoxemia (oxygen saturation, 77% without supplemental oxygen and 92% with 10 l/min supplemental oxygen). CT angiography revealed a saddle pulmonary embolism, with thrombi extending to all lung lobes, and minimal signs of right heart failure, including straightening of the intraventricular septum (Figure 2). The patient was transferred to intensive care unit (ICU) and started on therapeutic dalteparin (18,000 IU/day). A venous ultrasound confirmed deep vein thrombosis in the left popliteal vein.

Despite receiving dalteparin, the patient’s condition deteriorated, and she developed respiratory insufficiency. Given the increased risk of epidural hematoma due to the recent removal of epidural catheter, thrombolytic therapy was contraindicated, and a mechanical thrombectomy was performed. This procedure was complicated by catheter perforation of the pulmonary artery, resulting in mild hemoptysis.

That evening, the patient developed neurological symptoms, including arm paralysis, hemianopia, and aphasia. CT perfusion imaging showed a thrombotic occlusion of the M2 division of the right middle cerebral artery (MCA) with signs of recent ischemia. Although a thrombectomy was planned, the symptoms resolved prior to surgery. Over the following days, the patient experienced intermittent neurological deficits consistent with a stuttering stroke. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) revealed atrial septal deviation and a right-left shunt due to a small patent foramen ovale (PFO). The patient was subsequently prescribed clopidogrel 1 × 75 mg and an increased dose of dalteparin (2 × 10,000 IU/day).

Simultaneously, the patient developed gastrointestinal bleeding from a gastric ulcer, which was managed with hemoclips and adrenaline.

After 16 days in the ICU, the patient was transferred to the medical oncology department for 21 days and discharged to a rehabilitation center 37 days after the collapse. The patient achieved a complete oncological remission during response evaluation after three months, and the remission is currently extending.

Summary of case 3

A 66-year-old, non-smoking obese woman (BMI, 36 kg/m2) without comorbidities, with a FIGO stage IIIC1 (radiological T1b1N1M0) adenocarcinoma of the cervix, received 45 Gy EBRT combined with cisplatin, which was switched to carboplatin after two cycles due to nephrotoxicity (eGFR, 41 ml/min/1.73 m2, serum creatinine level of 120 µmol/l compared with pre-chemoradiotherapy values of eGFR > 90 ml/min/1.73 m2 and serum creatinine level of 74 µmol/l). HDR brachytherapy was initially delayed due to a failed applicator placement, but three weeks after completing chemoradiotherapy, HDR-brachytherapy was administered with an immobilization period of 29 hours.

Within an hour after applicator removal, the patient collapsed after a brief walk, became unconscious and gasping. After spontaneous return of circulation, she had tachypnea (30 per min) and hypotension (60/35 mmHg), along with profuse vomiting. Her ECG showed a right bundle branch block, and she was transferred to the ICU for observation. Blood tests revealed elevated lactate levels of 6.3 mmol/l and increased troponins, but cardiac analysis was inconclusive. The patient fully recovered spontaneously. The primary diagnosis of vasovagal collapse was established, and she was transferred to the medical oncology ward.

Three days post-collapse, the patient experienced a recurrence of symptoms. CT angiography revealed massive saddle pulmonary embolism, extending from the pulmonary trunk to the subsegmental branches on both sides (Figure 3). Therapeutic anticoagulation (dalteparin 18,000 IU/day) was initiated and the patient was discharged 11 days after collapsing. However, she was re-admitted two months later due to abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. A CT scan showed metastatic disease, outside the radiated area. Despite the implementation of best supportive care approach, the patient died three months later.

Discussion

Here, we described three cases of near-fatal saddle pulmonary embolism shortly after brachytherapy for the treatment of locally advanced cervical cancer. All patients collapsed within a few hours after brachytherapy applicator removal, coinciding with mobilization. Cervical cancer patients have therefore an increased risk of life-threatening VTE following immobilization during brachytherapy.

Gynecological cancer patients are classified as “high-risk” for VTE development [7]. The reported incidence of VTE in cervical cancer patients differs widely, ranging from 4% to 40% [8, 9]. This wide range is attributed to various independent personal-, tumor-, and treatment-related risk factors [10]. Specifically, advanced stages of cervical cancer, often associated with large solid pelvic tumors, are independent risk factors for VTE [9]. While early stages of cervical cancer are generally treated with surgery, advanced stages require treatment with chemoradiotherapy followed by brachytherapy [2]. Unlike patients treated with surgery, there are no specific guidelines for VTE prevention for patients treated with chemoradiotherapy and brachytherapy. Most guidelines, such as those from the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (ISTH), address VTE prophylaxis in broader oncological contexts, recommending risk stratification and prophylaxis for high-risk patients [11-14]. These recommendations also apply to patients receiving radiotherapy, although brachytherapy is often not specifically mentioned.

Currently, MRI-guided HDR brachytherapy is widely adopted for locally advanced cervical cancer. This approach aims to optimize local tumor control while minimizing major side effects, particularly, urinary, gastro-intestinal, and gynecological complications [2]. Although, cancer and anti-cancer therapy, specifically platinum-based chemotherapy and pelvic radiotherapy, are well-known independent risk factors for VTE, there is limited data on brachytherapy-related VTE [4, 16]. One study by McAlarnen et al. reported on a VTE incidence of 25% in patients undergoing inpatient admission for the treatment of gynecological cancer using brachytherapy [15]. While pulsed-dose-rate (PDR) brachytherapy is believed to contribute to the risk of thromboembolism due to prolonged immobilization (approximately 72 hours) in an inpatient setting, HDR brachytherapy, as administered in our three cases, typically involves shorter immobilization periods. HDR brachytherapy is usually delivered in three or four fractions, with immobilization ranging from less than 10 hours for single fractions and up to approximately 30 hours (maximum) for double fractions with an overnight stay. For immobilization in bed, the patient is positioned supine with log-roll precautions, with bladder catheter in place and intravenous pain management. The patient is allowed to move her legs, and if necessary, the legs are supported. High-dose thromboprophylaxis was prescribed only during immobilization.

Another explanation of brachytherapy-related VTE could be local pressure on the iliac veins by brachy applicator, leading to venous stasis. Upon removal of the applicator, a sudden decrease in pressure might cause the thrombus to shift.

Despite the shorter immobilization period during HDR brachytherapy, saddle pulmonary embolisms in our cases occurred shortly after mobilization following applicator removal. This discrepancy may be attributed to several contributing factors for VTE, including the underlying malignancy (often large tumors), platinum-based chemotherapy, pelvic irradiation, and personal factors, such as obesity [3-6]. In this case series, two of the three patients were severely obese. It could be hypothesized that asymptomatic VTE developed in weeks prior to brachytherapy, was triggered by these multiple factors, and manifested as symptomatic VTE upon patient mobilization. In clinical practice, the incidence of symptomatic VTE might be reduced by screening for subclinical VTE prior to brachytherapy, and by initiating subsequent treatment when silent VTE is detected [17]. D-dimer, a fibrin degradation product, can serve as a preliminary screening tool for hypercoagulability. While a negative D-dimer can exclude VTE [18], positive results in cancer patients often necessitate confirmatory venous ultrasound imaging due to elevated baseline levels [16]. A study conducted in 2019 demonstrated a negative predictive value of 100% and a positive predictive value of 50% for D-dimer levels in cervical cancer patients [19]. In this study, only patients with elevated D-dimer levels and a clinical suspicion of VTE underwent ultrasound imaging of the lower extremities, potentially missing silent VTE To ensure detection of both clinical and subclinical VTE events, pre-brachytherapy screening should include D-dimer measurement and ultrasonography of the lower extremities. This conclusion is supported by a study conducted by Murofushi et al., which recommended measuring D-dimer levels before and after brachytherapy to detect the incidence or worsening of VTE [20]. Moreover, McAlarnen et al. suggested to apply risk assessments tools to identify patients at risk for VTE and those who might benefit from prophylactic anticoagulation [15].

To reduce symptomatic VTE in future patients, routine thromboprophylaxis could be initiated at the start of definitive chemoradiotherapy and brachytherapy. To investigate this hypothesis, we conducted a prospective, observational cohort study in two Dutch tertiary hospitals, examining the incidence of clinical and subclinical VTE in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer receiving high-dose thromboprophylaxis during definitive chemoradiotherapy and brachytherapy [21]. Despite the prescribed thromboprophylaxis, among the 89 included patients, seven patients (7.9%) were diagnosed with VTE, of whom three (3.4%) had subclinical VTE diagnosed during pre-brachytherapy screening, and four (4.5%) had clinical VTE. Based on these findings, we concluded that routine thromboprophylaxis resulted in a relatively low incidence of VTE in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy and brachytherapy [21].

Unfortunately, there is lack of focused studies specifically investigating VTE incidence and prevention strategies in brachytherapy. This lack of evidence makes it difficult to formulate clinical guidelines tailored precisely for this patient group. Future research should focus on prospective data regarding VTE risks in brachytherapy, identifying patient- and treatment-related risk factors as well as developing customized prophylaxis strategies.

Conclusions

Pulmonary embolism represents a severe complication of chemoradiotherapy and brachytherapy. Given the high morbidity and mortality associated with this condition, routine thromboprophylaxis may be warranted. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to support specific guidelines for VTE management in this particular patient group. Therefore, it is important to follow existing general oncological VTE guidelines and perform individual risk assessments in patients undergoing brachytherapy.