INTRODUCTION

Despite the soccer game being predominantly dependent on aerobic metabolism, it can be argued that the most decisive actions are covered by the anaerobic metabolism (i.e., sprinting, jumping, etc.). The intermittent character of a soccer game results in a succession of high-intensity activities and periods of low intensity during which the players recover [1]. The relevance of aerobic fitness has been underlined because it correlated with the total distance covered during a match [2], particularly at high intensity [3]. More recently, it has been argued that the ability to repeat high-intensity activities is only partially related to aerobic capacities [4]. Nevertheless, peak oxygen uptake (

Maximal

Access to normative values is an essential component of evidencebased coaching. Normative values provide a standard against which individuals can compare their own performance and fitness. This helps set realistic goals and expectations for improvement. Understanding where an individual’s performance stands in comparison to the norm can guide the development of appropriate exercise regimens that target areas requiring improvement while capitalizing on existing strengths. Normative values are derived from large datasets, and this might be problematic when dealing with elite athletes because data on such athletes are more parsimoniously collected and shared. Moreover, the data for the Italian Serie A championship, one of the most popular in Europe, were unavailable.

The study aimed to provide reference cardiorespiratory values of first-division soccer players measured during a ramp exercise running test. Previous studies on elite soccer players [5–8] found that cardiorespiratory parameters extracted from CPET decreased with age and were influenced by playing position and season phase. Therefore, the reference values herein were stratified for age, playing position, and season phase. A large database of CPET collected over a decade on Serie A teams in Italy provided the potential for rigorous reference of the abovementioned parameters with a cohort of elite athletes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

This was an exploratory, observational, follow-up study of 451 professional male soccer players, aged between 16 and 38 years, belonging to 10 Italian “Serie A” league soccer teams. The players were tested from 1 to 5 times across the observational period; therefore there were 741 available data points. The population was examined in the period July–May of each year (from 2009 to 2017) from preseasonal training until the end of the tournament according to a standardized protocol consisting of clinical and functional assessment parameters. The clinical assessment included history of risk behaviour and physical examination, and the functional assessment included spirometry and ergospirometry. After receiving the description of the procedures and potential risks, all subjects gave their written informed consent. All procedures performed in the study complied with the ethical standards of the Internal Institutional Review Board Committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments or with comparable ethical standards. Players were unaware of the aim of the study and researchers performing analysis of results were blind to players’ identity.

Gas measurements

For the ergospirometric test (Vmax Encore, Yorba Linda, CA, USA), we used a breath-by-breath analysis of the flows fractional inspired and expired O2 and CO2 concentrations (FiO2, FeO2, FiCO2, FECO2) obtained via mass flow and fast-responding gas analysers (fuel cell and infrared analysers). Breath-by-breath data collected during each incremental test were time-averaged over 10 s. The following variables were obtained: oxygen uptake (

Procedures

An incremental symptom-limited exercise test was performed on a treadmill (Runrace 900, Technogym, Gambettola, Italy) under HR monitoring (Polar, Kempele, Finland). Subjects standing on the treadmill breathed through a mask. A continuous “ramp” protocol at constant grade (1%) (starting from 8 km/h, increasing speed by 1 km/h every 60 seconds) was used. The test was stopped when subjects complained of exhaustion. Exercise tolerance was evaluated as the maximal speed reached (maximal exercise velocity: MEV), adjusted according to a modified Kuiper’s equation: MEV (km/h) = velocity last stage completed + [t (s)/stage duration (s) × stage increment], where t is the time of the uncompleted stage expressed in seconds [9].

Statistical analysis

The

RESULTS

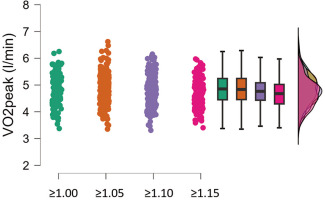

RER criteria

The soccer players reached RER ≥ 1.00 on 727 occasions (frequency 94%); RER ≥ 1.05 on 596 occasions (frequency 77%); RER ≥ 1.10 on 366 occasions (frequency 47%); RER ≥ 1.15 on 172 occasions (frequency 22%).

Normative data

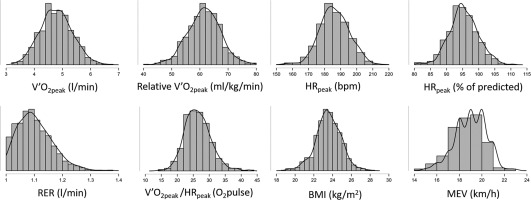

The normative data calculated over 727 occasions with RER ≥ 1.00 are reported in Table 1 and Table 2. We found an average

TABLE 1

Descriptive statistics of normative values

TABLE 2

Descriptive Statistics of secondary data

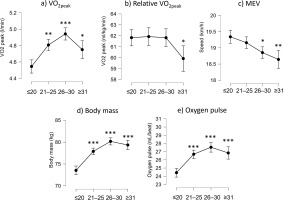

Age

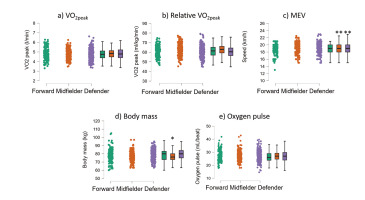

Playing role

Figure 4 shows the different distributions of the most relevant variables between playing roles. ANOVA showed that absolute

Pre-season vs in-season

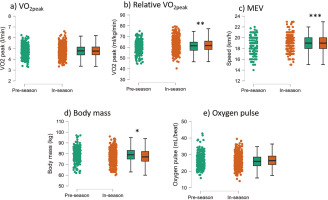

We found minor differences when comparing in-season and preseason results (Figure 5). While absolute

DISCUSSION

A database of 727 graded exercise tests was adopted to determine relevant cardiorespiratory reference values for Italian first-division soccer players. We found an average

The traditional standard for determining

Normative values in exercise and sport science provide a framework for setting goals, monitoring progress, and tailoring training programmes. The present study provides the distribution (see Table 1 and Figure 2) of cardiorespiratory parameters from a large sample (451 players tested on a total of 727 occasions) of first-division Italian soccer players. We found a

The effect of age on elite soccer players’ cardiorespiratory parameters was diverse (Figure 3). Indeed, absolute

Midfielders were the players with the highest relative

Soccer players in our sample reached higher peak exercise velocity in the in-season than pre-season (Figure 5). This is in line with previous studies [5], and it is an expected result. The tests were conducted after at least four weeks of soccer-specific training. However, the increase in maximal exercise velocity was not due to the rise in absolute

As the present study is based on real-world settings, there are some limitations that are typical of contexts dealing with top-level athletes. For example, the athletes stand quietly on the treadmill for only one minute before commencing the exercise instead of waiting at least 5 minutes as per standard procedures. This was due to the limited time available with the athletes. We could not obtain most of the athletes’ peripheral blood samples at the end of the exercise; therefore, we could not control the lactate concentration at exhaustion. On the other hand, the strength of the present study is that the findings are robust, considering the large dataset with over 700 data points. To ascertain whether the herein-reported level of

CONCLUSIONS

This study contributes to the understanding of the physical and physiological profile of elite soccer players. Our findings from a large data set confirm that