Purpose

The aim of the paper was to present a rare complication of orchiepididymitis in a patient treated with brachytherapy (BT) for prostate cancer, who underwent trans-urethral resection of the prostate (TURP) four weeks after BT treatment.

Case presentation

A 73-year-old patient with histologically confirmed prostate cancer (intermediate-risk group, cT1cN0M0 ISUP G3; prostate specific antigen [PSA] max. 11 ng/ml) was eligible for high-dose-rate (HDR) BT (2 × 13 Gy with 7-day interval), combined with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for 6 months (leuprorelin) [1-6].

The patient presented with lower urinary tract symptoms of moderate severity (International Prostate Symptom Score [IPSS], 12). In our hospital, BT is approved for patients with an IPSS ≤ 20. Laboratory tests and imaging studies were performed before BT. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

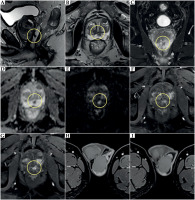

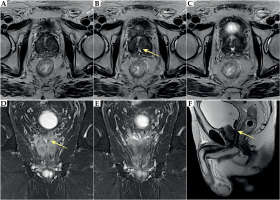

Pre-biopsy MRI images showed a focal lesion in the peripheral zone, in the posterior part located behind and to the left side of the urethra. Adenocarcinoma was confirmed by targeted biopsy (Gleason score 4 + 3). The lesion demonstrated low signal intensity on T2-weighted images, restricted diffusion, and marked early enhancement after paramagnetic contrast agent administration (Figure 1). Additionally, the prostate revealed features of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). MRI single scans of the testes and epididymides were normal.

Fig. 1

Prostate MRI before prostate biopsy and brachytherapy. A) Sagittal T2-weighted image, cancer (yellow circle) in the peripheral zone, enlargement of the transitional zone due to benign prostate hyperplasia. B) Axial T2-weighted image, cancer (yellow circle) in the peripheral zone behind and to the left of the urethra. C) Coronal T2-weighted image, cancer (yellow circle) in the peripheral zone. D) Axial image on ADC map, cancer in the peripheral zone behind and to the left of the urethra (yellow circle); low IS on ADC map, ADC value: –0.55 × 10-3 mm2/s. E) Axial image, DWI bmax 2000 s/mm2; cancer in the peripheral zone behind and to the left of the urethra (yellow circle), high IS on DWI. F, G) Focal enhancement on the peripheral zone in cancer focus (yellow circle). H, I) Normal testes and left epididymis before treatment

On day 2 after the first procedure, micturition disorders followed by urinary retention were reported. The patient was catheterized and instructed to exercise the bladder muscles. Next, HDR-BT was performed as planned. After urological assessment, the catheter was maintained for 7 days, while ADT was also completed.

ADT can decrease the prostate volume and reduce urinary symptoms to some extent. Therefore, urinary retention should not contraindicate ADT completion [6-8].

After elective removal of the catheter from the bladder, the patient reported another decrease in the urine flow, resulting in subsequent episode of urinary retention without clinical symptoms of infection. During catheterization, urine was collected for culture. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection (> 106) was sensitive to meropenem and gentamycin, and moderately sensitive to ciprofloxacin (MIC < 0.12 mg/l). Since there were no severe symptoms of infection nor need for hospitalization, treatment with fluoroquinolone was administered for 10 days. No bacteremia was found in follow-up examination. The patient was then electively referred to the Department of Urology for catheter removal 4 weeks after BT.

After another attempt to remove the catheter due to significant retention and poor urine stream, suprapubic cystostomy was performed and the patient was scheduled for TURP. Based on positive urine culture, meropenem was administered for five days. On the third post-operative day, the catheter was removed and good functional result was obtained (qmax 12 ml/s). Post-void retention was low, and follow-up urine culture was negative.

Four months after completion of BT and three months after catheter removal following TURP, the patient presented with severe left testicular pain without fever. Left epididymitis was diagnosed based on physical examination and testicular ultrasound. Empirical antibiotic therapy was introduced, and transient improvement obtained, while urine cultures were negative.

For eighteen months, the patient presented with many exacerbations of chronic inflammation, which progressed with the involvement of the left testis, without improvement after multiple courses of antibiotic therapy. Since the patient did not ejaculate after TURP, no semen culture could be obtained. During disease exacerbation periods, urinalysis for culture was regularly performed. When a positive culture result was reported, antibiotic therapy was administered based on antibiotic sensitivity testing, which resulted in slight improvement within 3-4 days; however, some symptoms were still present. When negative urine culture was reported, antibiotic therapy was administered empirically depending on symptoms’ severity (Table 1). In addition, there were scrotal fistula and fungal and bacterial infections found during the most severe inflammatory testicular infiltration with skin involvement (Table 2).

Table 1

Urinalysis and urine cultures

Table 2

Culture data

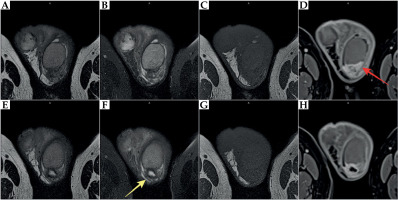

Ultrasound showed hypoechoic infiltrative lesions with increased flow on Doppler imaging, involving the left epididymis and testicular pole with a small abscess. During the most severe clinical symptoms, infiltration also involved scrotal skin. Similar lesions were found on MRI (hyperintense images on T2-weighted images with saturation of fat tissue, with very strong diffuse enhancement and small non-enhancing abscesses in the central part) (Figures 2-4).

Fig. 2

MRI at 10 months after brachytherapy. Inflammatory infiltration of the left epididymis (red arrow) with abscess formation involving the left testis (yellow arrow). A, E) T2-weighted images. B, F) T2-weighted images with fat saturation (FS). C, G) T1-weighted images. D, H) T1-weighted FS images with contrast enhancement

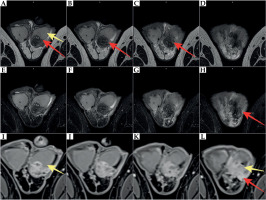

Fig. 3

MRI at 22 months after brachytherapy. Inflammatory infiltration of the left epididymis (red arrow) involving the left testis (yellow arrow). A-D) T2-weighted images. E-H) T2-weighted images with fat saturation (FS). I-L) T1-weighted FS images with contrast enhancement

Fig. 4

Ultrasound examination at 23 months after brachytherapy. A, B) Inflammatory infiltration of the left epididymis involving the left testis (yellow arrow), with inflammatory infiltration of the skin and subcutaneous tissue (red arrow). C) Inflammatory infiltration with pathological increase of flow in Color Doppler

As a result, left orchiectomy was performed two years after BT, and histological findings revealed chronic orchiepididymitis with necrosis. However, features of specific inflammation, such as tuberculosis, were not found. Testicular parenchyma showed signs of partial atrophy of spermatogenesis. Approximately 4 weeks post-operatively, the patient started reporting pain of varying intensity in the left half of the scrotum and groin. On a scrotal ultrasound, slight inflammation without abscess formation was found.

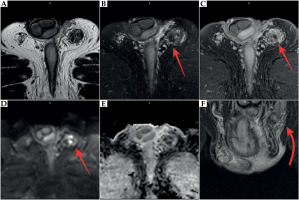

For the next 1.5 years post-orchiectomy, recurrent inflammation persisted with pain of different severity (from slight to moderate), without fever, and with minor inflammatory changes shown on ultrasound in the post-operative bed and in the left groin with no abscess. MRI images displayed lesions in the post-operative bed and in the left groin, with diffuse band-like strong contrast enhancement and small foci of diffusion restriction (micro-abscesses) (Figure 5).

Fig. 5

MRI at 5 months after left orchiectomy, 30 months after brachytherapy. Inflammatory infiltration with small abscesses and post-operative lesions in the bed of the left testis and in the left groin (red arrow). A) Axial T2-weighted image. B) Axial T2-weighted image with fat saturation (FS). C) Axial T1-weighted FS image with contrast enhancement. D) Axial DWI bmax 2000 s/mm2 image. E) Axial image on ADC map. F) Coronal T2-weighted image

These conditions required administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics (diclofenac; diclofenac + vit. B complex, diclofenac + omeprazole, nifuratel + nystatin, metamizole). Inflammation of the lower urinary tract and abnormal urinary findings (leukocyturia) were observed several times.

The final MRI performed 32 months after the end of treatment showed a complete regression of prostate cancer after BT. However, an irregular position of the prostatic urethra was observed, especially in the region of the vas deferens outlet as well as residual inflammatory changes in the scrotum and the bed after left orchiectomy.

On the follow-up MRI, the prostate was smaller compared with baseline measurements pre-treatment. No lesions corresponding to neoplastic infiltration were visible, indicating complete tumor regression. The nodules in the transitional zone decreased in size.

Additionally, deformities of the transitional zone were seen following TURP, with distortion of the verumontanum and irregular left seminal vesicle orifice, which was difficult to visualize. Furthermore, the seminal vesicles and ampullae of the vas deferens enhanced after contrast administration (Figure 6). The level of PSA nadir was 0.289 ng/ml at 36 months after treatment, and remained stable.

Fig. 6

Prostate MRI at 8 months after left orchiectomy, 33 months after brachytherapy. Post-operative defect in the transition zone with abnormal position of the urethra and the promontory area. Asymmetry of the seminal vesicle orifice on the left (yellow arrow). A-C) Axial T2-weighted images. D-E) Coronal T2-weighted images. F) Sagittal T2-weighted image

Discussion

HDR-BT combined with 4-6 months of ADT administration is the standard treatment option for patients with intermediate-risk prostate cancer, especially in centers with expertise in BT utilization [1-4, 7, 9-11]. The risk of late and severe urinary complications (G3 and above) in patients undergoing BT alone is quite low (maximum, 10%) [7, 12, 13]. Approximately 1-2% of patients experience urinary retention, but usually these symptoms resolve several weeks after catheter implantation. Studies have found that the severity of urethral irritation resolves after maximum of 5 years [7, 10].

According to recommendations, TURP is not a contraindication to BT [14]. However, the time period between prostate resection and implantation must be minimum 3 months [15-18].

There is no consistent clinical data on the use of TURP after BT. Flam et al. found that the risk of complications after TURP following prostate irradiation was several times higher [16].

The decision to perform TURP after BT should be tailored and based on detailed patient medical history, with prior episodes of prostatitis, their duration, and frequency of symptoms as well as the presence of voiding dysfunction. Prostate volume is also an important aspect.

According to EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer – 2024, about 1.5-22% patients experience urinary retention following implantation, and TURP is required in up to 8.7% of cases, with incontinence also reported (0-19%) [6].

Another serious complication is urethro-rectal fistula [15-18]. Based on our internal protocol, TURP should be performed at least 3 months after BT. According to studies, the most likely course of recurrent left epididymitis is due to the deformity of the prostatic urethra and overgrowth of the left vas deferens outlet [7, 19, 20].

TURP is the most common method for treating benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Traditional TURP is performed by careful removal of the apical tissue around the verumontanum [21].

Even in the absence of prior radiotherapy, TURP can induce significant tissue lesions, such as fibrotic and scar changes, in the region of the verumontanum, depending on surgical technique. Physical removal of prostatic adenoma tissue is inevitably linked to the loss of antegrade ejaculation due to disruption of the ejaculatory apparatus [22].

In their study, Sibona et al. presented an ejaculatory apparatus that was very complex from anatomical point of view. The authors provided a synthetic literature review about the ejaculation-sparing techniques for BPH surgery [23]. According to the literature, up to 73% of patients do not regain normal sexual function following TURP [21].

Ejaculation disorders are related to retrograde ejaculation, while pathophysiology of ejaculation disorders after BPH surgery is not fully recognized. It seems that preservation of the verumontanum borders and the bladder neck, can reduce the risk of post-operative adverse effects [23]. The aim of modern treatment methods for BPH, including minimally invasive surgical techniques, such as HoLEP, is to minimize tissue damage around the verumontanum to reduce significant risk of ejaculation dysfunction and preserve antegrade ejaculation [21-23]. The mechanism and severity of symptoms in our patient may be related to the lack of preservation of antegrade ejaculation.

Another more prevalent mechanism is associated with the obstruction in the prostatic urethra and the return of urine into the seminal duct.

Some investigators have reported that TURP before or after RT increases the risk of genitourinary (GU) toxicity, including urethral strictures and incontinence [24]. One of the complications of benign prostate hyperplasia is recurrent epididymitis [25-29]. Our patient was an asymptomatic carrier of aggressive bacterial strain, which became evident after HDR-BT. Currently, asymptomatic bacteriuria is not an indication for treatment if no additional factors are involved [30]. However, in the case of urinary tract procedures, bacteriuria should be treated [19, 31-34]. Therefore, it seems necessary to perform a urine culture prior to any surgical intervention, such as prostate biopsy or radiotherapy, which may lead to the activation of infection due to a change in urinary tract dynamics, e.g., causing an obstruction of urine outflow. Urinary retention was reported after the first BT implantation, resulting in an unfavorable course.

Tamalunas et al. compared the number of complications following TURP and HoLEP in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) secondary to the bladder outlet obstruction. Complications in the form of orchiepididymitis were not observed in their study [35].

Conclusions

Extreme caution regarding TURP should be exercised in patients undergoing BT. Conservative and pharmacological treatment must be introduced in the occurrence of urinary disorders after BT, while any intervention (i.e., TURP) should be performed at least 3-6 months after BT, which is crucial, especially in the case of development of radiation outcomes over time.

Less invasive surgical techniques for treating BPH should be considered in patients after BT. Combined adverse effects resulting from two invasive procedures for prostate treatment performed within a short time interval (i.e., treatment for BPH and prostate cancer), may lead to serious and life-threatening complications.