Purpose

Keloids are benign fibro-dermal tumors, which produce an excess deposit of extra-cellular matrix as a result of an increase in the synthesis of collagen and a decrease in its breakdown. They usually appear after a skin injury and extend beyond wound’s edges; they are characterized by high-rate of recurrence after excision and lack of tendency of spontaneous involution. Both the traits are visibly pronounced when keloids grow larger in size and became more symptomatic [1-4]. Keloids are not usually described in tissues lacking dermis. Even tough they generally develop during the first year after skin trauma, they have been described as of unknown etiology in case when the patient is not able to associate it with any previous injury [5]. Keloids are located mainly on the thorax, shoulders, and in the cervico-facial region, with a special predilection for the earlobes. They generally present with pain, pruritus, dyschromia, and functional limitation if located close to a joint. Epidemiologically, they affect young individuals (it is unusual to find them at old ages), affecting both sexes equally, with a family tendency (autosomal dominant and recessive), and are markedly more frequent in the Hispanic, Black, and Asian populations.

Treatment of keloids is both traditional and wide-ranging, such as simple excision, with recurrence rates of up to 100% [1-4], or intra-lesional injections of triamcinolone acetonide, dexamethasone 21-phosphate ± hyaluronidase, botulinum toxin type A, and interferon [2, 6-8]. Trigon® is the most widely used product, administered in doses ranging from 10 to 40 mg/ml in several applications, with a response rate of 50-100%, but with a 5-year recurrence rate of 10-50%.

Pressotherapy is a very common methodology, with 70-100% improvements reported in 60% of patients [4, 5]. Application of topical silicone shows a little improvement in 75% of all treated patients, and this effect is probably due to the occlusion and maintained humid environment, rather than to the effect of silicone components. However, the combination of silicone occlusion and pressotherapy provides a lower recurrence rate [4, 8]. Laser is another approach that may be used, especially CO2 laser, with recurrence rates of 40-90% reported [4, 5, 8]. Moreover, cryotherapy is a fairly widespread and well-documented method, where 1 to 3 cycles of 10 to 340 seconds of 1 cm3 are applied. Improvements of up to 74% have been described in a single month, especially in combination with intra-lesional corticosteroids. This mechanism functions through induced injury and tissue necrosis [9], and has a recurrence rate of 0 to 24%, with dyschromia and pain as the most frequent complications, being more effective in primary keloids than in resistant or recurrent ones [9-12].

Recently, a combination of surgery and interstitial brachytherapy has gained relevance. Recurrences rates of 16-21% have been reported in the first year, as compared with 45-100% with surgery alone [3, 12-14].

Brachytherapy with its great benefit of allowing the administration of high doses of radiation without damaging surrounding healthy tissues and causing few side effects, proved to be very efficient. It is applied alone or in combination with surgery, being more effective in the latter [13-17].

Although brachytherapy is commonly used in the treatment of different cancer types, it can also be employed in the prevention of keloids’ development [13]. When applied in a keloid treatment, the most common side effects are mild edema, depigmentation, and delayed healing [3, 13, 14, 16].

Even though the combination of surgery and brachytherapy can be found in the literature from previous 30 years [1], its utilization has spread more significantly over the last decade.

Material and methods

Study design and participants

In November 2020, a descriptive, observational, and retrospective study was designed. Participants were patients diagnosed with keloids, treated with surgery and brachytherapy, with a follow-up of not less than 1 year (as this period is considered with the highest recurrence rate) were included in the study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Procedures

Surgery was performed by plastic surgeons under local anesthesia alone or combined with sedation, depending on the size of keloid and patient’s tolerance. Extra-lesional excision of a keloid without a margin was carried out, after which a 6F brachytherapy catheter was placed at a depth of 0.5 cm. The area was closed using subcutaneous and intradermal sutures. Initially, a conservative regimen of 5 Gy in 3 fractions was chosen, administered every 6 hours, for 36 hours from the surgery. Since 2014, after a bibliographic review and participation in a national study project, the dose was modified to 6 Gy in 3 fractions, except for keloids located in the cervico-facial region, where the 5 Gy/3 fractions regimen was maintained. The current gold standard is 18 Gy in 3 fractions, considered the most effective, with the lowest rates of recurrence and adverse effects.

During the first six hours after surgery, after planning CT scan and 3D dosimetry, the patient was treated with high-dose interstitial brachytherapy. Second and third fractions were applied at 24 and 30 hours post-surgery. After last fraction, the catheter was removed in the Radiation Oncology Unit, and the patient was discharged from the hospital for periodic monitoring in outpatient clinics.

Outcomes

The recorded data followed a bibliographically evaluated scheme [14, 19]. Study variables may be found in Table 1.

The primary endpoint was to evaluate the recurrence rate of keloid scars using the combined treatment of surgery and brachytherapy, and to compare it with the recurrence rate described in the literature using surgery alone. Recurrence was sub-divided into early (during the first year post-treatment) and late as well as partial and total. The secondary objective was toxicity, classified as minor or major, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2

Categories of complications based on severity

| Minor complications | Major complications |

|---|---|

| Radiodermatitis grade I/II | Radiodermatitis grade III/IV |

| Dehiscence for < 3 months | Chronic wound for > 3 months |

| Mild dyschromia | Severe dyschromia |

| Infection |

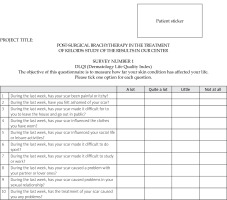

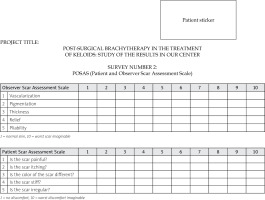

After the literature review, two scales were chosen for the subjective assessment of results, including dermatology life quality index (DLQI) with its cross-cultural adaptation to Spanish (Indice de Calidad de Vida en Dermatología), and patient and observer scar assessment scale (POSAS). The POSAS scale measures the characteristics of the scar subjectively: the point of view of the patient and the healthcare worker as an external observer (Annex 1). Whereas the DLQI scale does not directly assess the scar, but rather the impact it causes on the patient’s quality of life. Since dermatological pathologies significantly influence patients’ quality of life, this type of scale was chosen. The DLQI scale has good-to-excellent internal consistency and high Spearman coefficients in its reliability assessment (Annex 2).

Results

From May 2012 to September 2019, 27 patients were treated with this therapeutic combination at our center. The obtained data were analyzed by the Biostatistics and Scientific Coordination Unit of Biocruces. Continuous variables with normal distribution were expressed with mean and standard deviation, while those without normal distribution were presented with median and interquartile range. Categorical variables were shown as percentages. Differences between the groups were calculated using chi-square test for categorical variables, and Student’s t test for normal continuous variables and Mann-Whitney U test for non-normal continuous variables. All analyses were carried out using R®, version 4.0.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

The mean age was 41.7 (±14.5) years, 56% were males, and 72% of the patients had Fitzpatrick I/II skin type. 64.7% of the participants have been treated previously with corticosteroid infiltrations, laser, or simple excision. The most common etiology was previous surgical incision, followed by piercing. 64% of the patients presented with pain and 37.5% with pruritus. The mean diameter of lesion was 6.5 (range, 4-16) cm2. All patients were treated with 3-fraction brachytherapy, and 76% received 15 Gy. The median follow-up was 4 (range, 1-6) years after treatment completion. The relapse rate in bivariate analysis was 25%, of which 83% of the cases were partial relapses, with 83% of those who had a recurrence developed it in the first year post-treatment. 68% of the patients presented complications associated with the treatment, but only 7% had major complications, most frequently delayed healing beyond 3 months (3 cases) and grade III/IV radiodermatitis (2 cases). 61.1% of the cases developed minor complications, mainly dehiscence (4 cases) and infection (3 cases).

From the assessment scales, the questionnaires indicated very favorable results regarding scar quality. The mean DLQI survey rate was 0, with an interquartile range of 0-5. The mean POSAS scale rate was 11 (range, 7-14) for the observer and 11 (range, 5-19) for the patient.

Discussion

A keloid is a scar that extends beyond the limits of the original injury, and originates from surgical treatments, accidents, micro-traumas, and unknown causes. It is due to an excessive and/or prolonged response of the inflammatory phase of healing due to overexpression of growth factors and interleukins, which stimulate the proliferation of fibroblasts and the synthesis of collagen.

A keloid is a pathology that is difficult to treat, and has high recurrence rates, for which multiple therapeutic approaches are proposed, including the injection of intra-lesional corticosteroids or other substances (imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil), pressotherapy, application of topical silicone, laser therapy, and cryotherapy.

In recent years, the technique considered the gold standard for the treatment of recurrent keloids and/or keloids resistant to other treatments is the extra-lesional excision and application of interstitial brachytherapy [12, 14, 16-20].

Cruces University Hospital adopted this technique in 2012 for the treatment of keloids resistant to conservative treatments.

The current study was a descriptive and retrospective in nature, although it is understood that this type of study is not as powerful as experimental studies, with case-control for hypothesis testing. A dose-fractionation of 5 or 6 Gy (depending on the location) in 3 fractions given during the first 36 hours after excision was chosen. Even though there are studies reporting higher [21] or lower doses [3, 14, 15, 19, 22-25], and higher [25, 26] or smaller fractions [3, 14, 19, 23], the largest and most recent trials have described the lowest recurrence rate with acceptable complication levels using the dose-fractionation selected [17, 18, 27-30].

The primary objective of this study was the recurrence rate after combined treatment compared with simple excision. We also analyzed the rates of minor and major complications, and quality of life using the POSAS and DLQI scales.

The primary objective of the study was the recurrence rate after combined treatment compared with simple excision, resulting in 8.25% of relapses. At this point, there is great variability of results in the literature, from those reporting recurrence rates of only 2% [18], from 4 to 20% [15, 16, 21, 26, 27, 30-33], from 20 to 30% [1, 3, 13, 19], from 30 to 40% [20, 22], and even greater than 50%, although these were seen as partial recurrences [7, 23, 30]. Comparing these results with ours, in Daudare et al. study, patient follow-up was only 6 months post-treatment, and subsequent recurrences might have not been documented [1, 20, 30, 34]. Likewise, some studies did not consider the partial re-appearance of keloid as hypertrophy, but rather as recurrence [24, 25]. On the other hand, a considerable percentage of our keloids were located on the trunk, and were extensive, old, and resistant to previous treatments, all characteristics associated with a higher recurrence rate [12, 14, 16, 21, 24, 26, 31, 32, 35].

Regarding demographic data, the results indicated that 56% of the patients were males, 72% had Fitzpatrick I/II skin type, the average period of time from the onset of the condition to the treatment request was 5 years, and the most frequent location of the keloid was around the ear (52%), followed by the thorax (24%). The average diameter of the keloid at the time of its removal was 6.5 cm, and the average time until treatment was 5 years. 64.7% of the patients studied have been treated previously with corticosteroid infiltrations, laser, or simple excision. The most common etiology of the pathology was a surgical incision, followed by piercing. 64% of the patients complained of pain, and 37.5% suffered from pruritus. These results are in line with the findings reported by other groups [14, 18-20].

68% of the patients presented some type of complication, of which only 7% were considered major complications. At this point, it should be emphasized that all major complications observed in our study were limited exclusively to chronic wounds taking more than 3 months to heal. Comparing our results with the literature, all studies reported low rates of major complications: between 1 and 25% [14, 18, 20, 24], and little higher, between 15 and 75% [15, 31] for minor complications. Regarding possible carcinogenesis associated with radiotherapy treatment of keloids, several studies emphasized the absence of objective data supporting this theory, establishing that the radiotherapy treatment of keloids is a safe approach [14, 18, 19, 26, 31, 36].

Finally, in the subjective evaluation of the results using the POSAS and DLQI scales, with few exceptions [3, 12, 23, 37], it is unusual to find quantifiable data, reporting only positive subjective evaluations of esthetic results. Considering the impact of the keloids on quality of life, due to the symptoms and esthetic alteration that might imply, evaluating this point was crucial to our team. We opted for the Spanish version of DLQI scale for the first assessment and the POSAS scale for the second. Very good results were obtained, with an interquartile range between 0 and 5 (a result of 0-1 in the DLQI scale, meaning that the scar has no impact on the patient’s life), and an average of 11 for both the observer and the patient (on the POSAS scale, where a numerical value between 5 and 50 is assigned, and the higher the score, the worse the scar), which again coincides with the rest of the authors [38-43].

Conclusions

The combination of surgery and interstitial brachy-therapy using 5-6 Gy dose in 3 fractionations during the first 36 hours after surgery is an effective well-tolerated technique, with acceptable toxicity and satisfactory objective and subjective outcomes. Investigations involving various techniques to treat keloids report mixed outcomes. Surgery followed by skin brachytherapy is a valid approach in the treatment of resistant or recurrent keloids. Prospective, randomized studies with larger sample sizes are necessary to obtain more statistically significant results.