Purpose

Cervical cancer (CC) is the second most common gynecologic cancer in the United States and the second leading cause of cancer death in women aged 20-39 years [1]. Since the 1970s, the overall incidence of CC has dropped by more than half, reflecting the impact of widespread uptake of screening and more recently, the development of the vaccine for human papillomavirus (HPV) [1]. Although these preventative measures have led to a significant drop in the overall incidence, there has been a widening in the existing geographic, socio-economic, and racial disparities in treatment and outcomes [2, 3]. Moreover, the largest geographic variation in cancer incidence and mortality in the US was detected in the most preventable cancers, such as cervical cancer, and the incidence of CC in Puerto Rico was 30% higher than the incidence among mainland Hispanic women [1, 4]. The survival of Black women was shown consistently lower compared with their White counterparts [5, 6].

The standard of care for locally advanced cervical cancer (LACC) is multimodality therapy, including chemotherapy, external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), and a brachytherapy (BT) boost [7]. The addition of BT improves overall survival (OS) compared with IMRT or SBRT as a boost, and the omission of BT has a more significant impact on survival than the exclusion of chemotherapy [8]. BT in the management of LACC has evolved from relying on 2D dosimetry, where intracavitary brachytherapy (ICBT) with tandem plus ovoid/rings delivered dose to specific reference points, to image-guided brachytherapy (IGBT), where CT and/or MRI are employed to optimize dose to tumor and reduce dose to normal tissues using 3D volumetric planning. With the advancement in 3D imaging and planning, there has been an improvement in utilization of interstitial needles to treat locally advanced disease, allowing for better coverage of target volume and better sparing of organs at risk, especially for larger tumors [7].

Despite the importance of BT in treatment outcomes for LACC, data suggest declining utilization of BT, particularly in patients without insurance, underrepresented minorities, and in low-volume cancer centers. The decline in brachytherapy among vulnerable populations may in turn widen cancer disparities [9]. Previous research has found that racial survival disparities between White and African American patients resolved when accounting for standard of care (SOC) treatment combining EBRT + BT [2].

Locally advanced disease often requires interstitial management to adequately treat the extent of disease, while radiation oncologists may not be trained, equipped, or comfortable performing interstitial implants. A survey of ABS members indicated the complexity of interstitial BT requiring specific training and tools as a potential reason for the underutilization of BT overall [10]. Hence, we hypothesized that patients treated at centers reporting higher number of LACC patients and/or treatment at an academic center would result in higher likelihood of receiving interstitial brachytherapy, which might translate to an improvement in OS. In this study, we utilized the National Cancer Database (NCDB) to examine the patterns and predictors of BT utilization, particularly interstitial BT, in patients with LACC, and its impact on OS.

Material and methods

Patient population and data selection

The NCDB is a nationwide cancer outcomes database for approximately 1,500 Commission on Cancer-accredited cancer programs, and capturing approximately 70% of newly diagnosed cancer patients in the United States. Data are collected and submitted using nationally standardized data item and coding definitions, as outlined in the Commission on Cancer’s Facility Oncology Registry Data Standards. Data reported from Commission on Cancer-approved hospitals are abstracted from patient charts by certified tumor registrars, who undergo training specific to cancer registry. All data submitted to the National Cancer Database undergo integrity checks, internal quality monitoring, and validity reviews. Additionally, every few years, surveyors from the Commission on Cancer evaluate each hospital’s data collection processes.

For the current study, the NCDB was used to identify patients with LACC (clinical FIGO stage IIB-IVA) diagnosed between 2004-2018, and treated with radiation that involved a component of BT. All histologies were included. Patients who received only BT or those with incomplete data were excluded from this cohort. Treatment groups were divided into patients who received EBRT + intracavitary BT vs. those who received EBRT+ interstitial BT. NCDB records on the type of high-dose-rate (HDR; intracavitary vs. interstitial) were acquired with the Standards for Oncology Registry Entry by institutional data registrars using radiation completion notes, with manual verification from treating physicians when needed. Hybrid (intracavitary + interstitial) applicators were captured as interstitial implants within this framework.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square tests were employed to compare categorical patient characteristics across brachytherapy groups, and Wilcoxon tests were used to compare continuous characteristics.

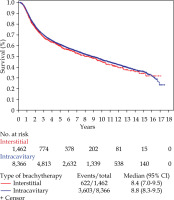

A logistic regression model was fit with clinically relevant predictors, such as race, nodes, T-stage, facility type, age, and Charlson-Deyo score, to estimate the probability of receiving interstitial brachytherapy treatment and to calculate propensity scores. Following this analysis, a Cox regression model was defined with the calculated propensity scores as a covariate, to examine the effect of brachytherapy group on OS. Finally, Kaplan-Meier methods were applied to plot survival curves by brachytherapy group.

Results

The total number of patients who met entry criteria was 9,829, with median age of 55 years. Table 1 depicts the characteristics of patients included in this study. Of the 9,829 patients who received some form of BT during primary treatment for LACC, the majority of patients (74%) self-reported as White, and the majority of patients had some form of insurance, with private insurance (39%) and governmental insurance (51%) most common. Overall, 1,463 patients (15%) received interstitial BT, and the majority of patients received chemotherapy as part of their treatment regimen (93%). There was a significant variation in rates of BT utilization based on geographic location and type of treatment facility (Table 1), and patients treated with interstitial brachytherapy were more likely to be treated at an academic center. Overall, the least number of brachytherapy cases was performed at community cancer programs (3.4% of cases) and in rural practices (2%).

Table 1

Patient characteristics

On multivariable logistic regression to predict receipt of interstitial brachytherapy (Table 2), a higher stage and treatment at an academic center were associated with increased interstitial BT utilization. African American patients were less likely to receive interstitial BT, as were patients with positive nodes. There was no significant association between age at diagnosis or comorbidity score and patterns of interstitial BT use. After propensity score matching, no OS difference between patients who received interstitial vs. those treated with intracavitary BT was observed (Figure 1, Table 3; HR: 0.985, p = 0.734).

Fig. 1

Kaplan Meier survival estimates for the overall patient cohort treated with interstitial vs. intracavitary brachytherapy

Table 2

Multivariable analysis of receiving interstitial brachytherapy

Discussion

Brachytherapy is a key component of the overall multimodality management of LACC [7]. Previous research suggested that BT utilization is declining across the nation, potentially due to decreased training, resource, and financial burden as well as a non-evidence-based movement towards delivering non-invasive EBRT boosts [2].

Several previous studies have found that Black women, uninsured, and government-insured women, are less likely to receive any form of BT [11-14]. On multivariable analysis, our study also found that race was a significant predictor of interstitial BT utilization, but insurance status was not able to be analyzed as it showed significant collinearity with some other variables of interest. The recent expansion of Medicaid benefits through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has been found to potentially reduce disparities in cancer care overall [15], particularly in receiving brachytherapy [16]. Moreover, a recent analysis of the NCDB, which included 17,442 patients who were treated with definitive chemoradiation between 2004 and 2014 for stage IIB-IVA CC, found that although BT utilization declined during 2008-2010 compared with 2004-2007, the rates of BT use recovered during 2011-2014 in all insurance groups, especially for Medicaid (OR: 1.44, 95% CI: 1.26-1.65) and uninsured patients (OR: 1.28, 95% CI: 1.03-1.57), which was attributed to the implementation of the ACA [17]. However, the use of brachytherapy could be negatively impacted by the much-debated implementation of RO-APM model, which represents an initiative from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services Innovation Center to transform Medicare reimbursement from a fee-for-service model to an episode-based payment model [18]. In anticipation of this proposed model, which has been delayed, several reports warned of its potential negative impact on BT utilization, given the financial de-incentivization for this particularly complex procedure if not adequately incorporated into the RO-APM model [19].

Similarly to previous reports [20-22], our data indicated that treatment at an academic center was predictive of significantly higher interstitial BT utilization [17]. This presents another potentially important consideration for the proposed RO-APM model, as the current proposals do not include a provision for dividing cancer care between two centers. Brachytherapy is often performed at a referral center, when a community site does not have the resources or expertise to perform high quality BT. Moreover, the model ties reimbursement to historical experience and trends of BT utilization, hence it is feared to widen the existing geographic disparities and continue to put rural communities at a disadvantage [23]. Recently published data from the EMBRACE-1 trial showed that at a median high-risk clinical target volume (HR-CTV) of 28 cm3, 40% of patients required a combined intracavitary and interstitial approach to achieve adequate tumor coverage [24]. In addition, the authors reported that the benefit of adding interstitial needles was highest for patients with larger tumors (HR-CTV > 30 ccs) [25]. It was reassuring to note in our analysis that among patients who received a BT boost, higher clinical stage was significantly associated with increased interstitial BT utilization. However, previous NCDB analysis of patients with LACC treated between 2004 and 2016 using chemoradiation and a boost (EBRT or BT), showed a significant association between higher FIGO stage and receipt of EBRT boost [21]. It is possible that even radiation oncologists who are comfortable with intracavitary brachytherapy, may not feel equipped to use interstitial needles in patients with bulky tumors. As reimbursement evolves over time, it will be important to make sure that reimbursement allows for complex brachytherapy to be performed in referral centers to deliver optimal care for all patients, including marginalized populations, which often present at advanced stages due to inadequate accesses to screening and/or vaccination programs [2].

In addition, it is important to note that the use of “Academic centers” in the current manuscript is a limitation of the NCDB data, and expertise and volume of brachytherapy implants are by no means fully captured with this variable. As has been shown in a previous report [20], the volume of patients treated and/or specific treatment center might have the largest impact on patient survival, independent of academic designation.

In terms of OS, after propensity score matching, the utilization of interstitial BT implant did not translate into an OS benefit, possibly due to the selection of cases that have poor initial response to chemoradiation and/or advanced stage of disease.

This analysis was subject to several inherent limitations of population database studies, such as the possibility of inaccurate coding, underreporting, and selection and reporting bias. This analysis was limited to patients who received radiation for LACC with a BT component. However, it is difficult to determine from the NCDB whether this has been performed with a definitive vs. palliative intent, which might influence the rationale behind the type of BT utilized, and hence, impact the analysis. Importantly, the NCDB only recently started to capture radiation treatment in distinct phases. The goal of 2018 implementation of separate phase-specific data items for the recording of radiation modality and external beam radiation treatment planning techniques, is to clarify these information and implement mutually exclusive categories; therefore, interstitial vs. intracavitary might not have been adequately acquired as distinct categories prior to this update.

Conclusions

The current work provides a unique analysis for interstitial BT utilization determinants in the management of LACC. It overall supports growing body of literature that BT utilization, irrespective of technique, is impacted by patient race and treatment facility. Our data show that patients with a higher stage cervical cancer and those treated at a high volume or at academic center were more likely to receive interstitial BT. This pattern possibly reflects appropriate intensification of therapy for larger tumors at centers with interstitial implant expertise. However, utilization of interstitial implant did not translate into an OS benefit. Further study could lead to improved understanding of barriers to accessing interstitial brachytherapy, and how current and proposed insurance as well as reimbursement models affect its implementation, in order to inform policy and efforts to ensure equitable and accountable care with brachytherapy.