Purpose

Prostate permanent brachytherapy is a well-established treatment for low- and favorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer (PCa) [1-6]. This outpatient procedure, usually performed under spinal anesthesia, is easy to perform, and most patients are able to resume their normal activities of daily living within a few days. However, the incidence of acute toxicity, mainly urological, is not negligible.

In recent years, major advances have been made in prostate imaging, most notably multiparametric (mp) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The emergence of this advanced imaging technology allows to predict the location of dominant lesion in the prostate with a high degree of accuracy. Also, it allows to determine whether the lesion is a localized, unifocal disease amenable to focal treatment.

The aim of focal approaches is to reduce the impact of treatment on urinary, sexual, and bowel functions. Modern focal treatments, all of which are image-guided, include cryotherapy, high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), vascular-targeted photodynamic therapy, laser ablation, thermal ablation, focal brachytherapy (BT), radiofrequency waves, microwave ablation, focal external beam radiotherapy (e.g., CyberKnife), and irreversible electroporation (e.g., NanoKnife) [7]. Of these focal techniques, BT is the only recognized oncological procedure able to deliver a specific quantity of radiation with detailed dosimetry [8]. Moreover, comprehensive guidelines for focal BT are available, ensuring high quality training and quality assurance. Focal prostate BT can target the involved lobe, known as hemi-gland HG BT (HGBT), or only the dominant lesion in that lobe, with a margin of safety. However, this approach, in which only a part of the prostate gland receives treatment, is controversial. To date, only a limited number of studies have assessed focal or HG prostate low-dose-rate (LDR) BT, and most of these studies have had small sample sizes and a short follow ups [2-4, 9-16]. Nonetheless, the reported 5-year local control rates are excellent (95-97%) and equivalent to whole-gland BT (WGBT), with low-rates of both early and late toxicity [2-4].

In this context, the Spanish Radiation Oncology Research Group (GICOR; in Spanish, Grupo de Investigación Clínica en Oncología Radioterápica) carried out a phase II clinical trial to compare the effectiveness and side effects of focal HGBT with WGBT in patients with low-risk and favorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer.

Material and methods

This was a phase II clinical trial involving patients diagnosed with low-risk or favorable intermediate-risk, single-lobe PCa. The trial was approved by the Ethics Committee at the Catalan Institute of Oncology on December 4, 2014 (registration number: AC133/13), and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrolment. To assess the differences in late toxicity, minimum sample size was calculated as 108 patients.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: 1. Estimated life expectancy > 10 years; 2. Diagnosis of histologically-proven prostate adenocarcinoma (≥ 10 biopsy cores, and ≤ 50% cancer in any biopsy core); 3. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 0 or 1; 4. Clinical stage T1c-T2a; 5. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) < 10 ng/ml; 6. Gleason grade ≤ 7 (3 + 4) in two cores or less in the involved lobe; 6. International prostate symptoms score (IPSS) ≤ 16; 7. MRI performed < 4 months before enrolment showing the presence of unilateral cancer (i.e., right- or left-sided only) or non-visible disease; 8. Prostate size < 60 cc at treatment initiation; 9. No previous hormonotherapy.

Outcomes

Primary outcome measure

Health-related quality of life (QoL) was assessed using a 26-item expanded prostate cancer index (EPIC), and patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) designed to assess health-related (HR) QoL in multiple domains (i.e., urinary, bowel, sexual, and hormonal). EPIC scores ranged from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better results [17, 18]. EPIC results obtained in the present trial were compared with historical data from a previously published study carried out by the Multicentric Spanish Group of Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer [19]. That study included a large cohort of patients (n = 179), who underwent real-time LDR-BT to the whole prostate gland with iodine-125 (125I) permanent seeds (145 Gy to the target volume).

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcome measures included treatment failure rates and toxicity, as registered in medical records during follow-up clinical visits completed by all participants in the trial. Treatment failure was defined as evidence of local clinical progression and/or biochemical failure, as described in previous studies on focal BT [20, 21]. Local clinical progression was defined as a positive biopsy, following radiologically suggestive findings on MRI or positron-emission tomography (PET) scan. Biochemical failure was classified as an increase in PSA levels ≥ 2 ng/ml above nadir, in accordance with the updated RTOG American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) Phoenix consensus panel [22]. Acute (< 6 months post-implantation) and late (> 6 months) genitourinary (GU) and gastrointestinal (GI) toxicities were assessed according to the common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE), v. 5 [23].

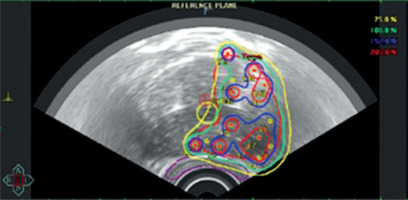

HGBT treatment characteristics

All patients underwent permanent implant of 125I seeds to a dose of 145 Gy to the involved lobe (Figure 1). Under spinal anesthesia, two harpoons were used to block prostate movement, and real-time ultrasound-guided implantation was employed in all cases. Oncentra Prostate Program (Nucletron, Elekta, B.V., Vee-nendaal, Netherlands) was used for real-time dosimetry, whereas stranded seeds (I-125 IsoCord®, Eckert & Ziegler) or robot-assisted seeds (Elekta Inc.) were applied.

The prescribed minimum peripheral dose to the prostate was 145 Gy, in accordance with the 2022 GEC-ESTRO ACROP prostate brachytherapy guidelines [8]. The urethra, bladder, and rectum were contoured to meet the following dosimetric constraints: clinical target volume (CTV) V100 ≥ 95%, D90 > 145 Gy, V150 ≤ 60%, rectum D2cc ≤ 145 Gy, D0.1cc < 200 Gy, urethra D10 < 150%, and D30 < 130%.

The number of implanted seeds ranged from 16 to 62, depending on the prostate size, with the exact number of seeds based on dosimetric calculations. Seed activity was 0.414 mCi in smaller prostates (< 45 cc) and 0.62 mCi in larger prostates (> 45 cc).

Follow-up

Patients were evaluated during treatment, and at 1, 3, and 6 months post-treatment. Subsequently, follow-up visits were performed at 6-month intervals until two years, and annually thereafter. PSA levels were determined every 6 months. Follow-up included imaging tests; a CT was performed at 4 weeks post-implant to assess implant quality and an mpMRI was performed annually thereafter. The EPIC questionnaire was administered by telephone by an experienced interviewer [17, 18] before treatment and at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months after treatment. This instrument was administered annually thereafter.

Statistical analysis

First a sample size of 108 patients was calculated to find differences in late toxicity. When we added the outcomes on quality of life, we determined that 38 patients treated with HGBT were enough to detect moderate differences between groups (effect size of 0.5 SD) in EPIC scores. Considering the number of patients treated with WGBT (n = 179), a statistical power of 80% and a significance level of 5% were calculated.

Summary statistics were reported to describe baseline patient characteristics, treatment-related variables, patterns of treatment failure, and follow-up duration. Post-treatment PROM outcomes were reported as figures, with mean EPIC-26 scores for the HGBT group vs. the historical WGBT cohort [19]. To compare changes between the two groups over time, while accounting for correlation among repeated measures, we constructed separate generalized estimating equation (GEE) models for each EPIC-26 score as the dependent variable. Time and study group were included in the models as categorical variables, and interactions between these variables were evaluated to test for differences in trends. Additionally, EPIC-26 mean of change from pre-treatment to each follow-up evaluation and their corresponding effect size (mean of change/SD of change) was estimated. General guidelines define an effect size of 0.2 as small, 0.5 as moderate, and 0.8 as large magnitude [24]. Time to event was measured from treatment initiation to failure, death, or most recent follow-up visit. Estimates were calculated with actuarial and Kaplan-Meier methods using IBM SPSS statistical software program.

Results

A total of 38 participants were included in the HGBT trial. The recruitment took place from 2016 to the 2020. The mean follow-up was 71.4 months (range, 44-93). Patient recruitment was slow, mainly due to the availability of multiple alternative treatments for this patient population (mainly low-risk PCa), including active surveillance and robotic prostatectomy. Due to this slow recruitment rate, we were unable to reach the sample size estimated for secondary outcomes (n = 108 patients) within the expected time frame, and the study was terminated in 2020.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients, treatments, and treatment failure indicators. The mean age of the patients was 64.9 years (range, 50-78). The tumor was left-sided in 22 patients and right-sided in 16. The mean PSA at baseline was 6.12 ng/ml (range, 1.53-10). All patients (37/38, 97.4%) had Gleason 3 + 3, except for one patient who had Gleason 3 + 4. Clinical staging was T1N0 in 34 patients and T2N0 in the remaining four patients. By MRI, staging was distributed as follows: stage T1c (n = 23), T2a (n = 9), T2 (n = 1), and no visible tumor in five cases (Tx).

Table 1

Patients characteristics and results

The mean (range) treated volume (V100) was 17.34 cc (range, 3.76-38.65). The median number of needles used was 12 (range, 7-18), and the median number of seeds inserted was 41.5 (range, 16-62). Seed activity was as follows: median = 0.504 mCi; mode = 0.409 (min 0.34, max 0.56 mCi). The mean total activity of the seeds measured at a distance of one meter (total Kerma rate) was 19.93 cGy.

The mean PSA nadir was 1.4 ng/ml (range, 0.17-4.24), and the mean time to nadir was 27.55 months (range, 2-87). The mean times to bio-chemical failure and local clinical progression were 55.34 and 60.18 months, respectively.

Quality of life

After completion of the treatment with HGBT, quality of life (QoL) measures decreased in multiple domains on the EPIC-26 (Figure 2). However, urinary and bowel sections both improved over time. Sexual impairment increased over the entire five-year follow-up period, while hormonal score remained quite stable. The only significant difference (p = 0.002) in QoL between the two groups [20] was in urinary irritative-obstructive symptoms, which were better in the HGBT group. The participants’ response rate to the EPIC questionnaire ranged 63-95% in our HGBT study, and 52-98% in the WGBT study [19].

Fig. 2

Patient-reported outcomes of patients treated with HGBT and of the cohort of patients treated with WGBT [19]

Figure 2 shows the EPIC-26 mean of change from pre-treatment to each follow-up evaluation and their corresponding effect size, which indicate small-to-moderate deterioration of urinary incontinence, large worsening of urinary irritative-obstructive and bowel domains (though only during the first 3 months after treatment), and sustained moderate-to-large sexual deterioration.

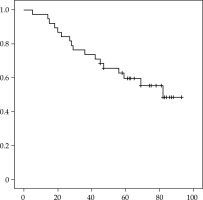

Disease control and changes over time

Figure 3 illustrates failure-free survival curves (Kaplan-Meier) for the HGBT group. Of the 38 patients, 17 (44.7%) developed biochemical failure, with a mean time to biochemical failure of 55.3 months (range, 5-82). The mean time to local clinical progression was 60.18 months. The 5-year biochemical control rate was 59.6%, indicating that slightly more than 40% of patients developed biochemical failure within five years. A total of 14 patients developed local relapse (confirmed by PET or biopsy), which was contralateral in nine patients, ipsilateral and contralateral in four patients, and regional in one patient (pelvic nodes).

Fifteen patients underwent salvage therapy as follows: contralateral LDR-BT (n = 7), high-dose-rate (HDR) BT (n = 3), nodal radiotherapy + hormonal therapy (n = 2), hormonotherapy alone (n = 2), and prostatectomy (n = 1). All of the patients who underwent salvage therapy were alive and without evidence of disease at last follow-up. At the last follow-up (median of 71.4 months), 23 of the 38 patients were alive and without biochemical failure, 12 were alive with biochemical failure, and three had died from other causes, while the mean PSA was 2.16 ng/ml (range, 0.01-17).

Chronic toxicity

Of the 38 patients, 16 developed urological toxicity (CTCAE-5), distributed as follows: grade (G) 1 (n = 14, 36.8%), G2 (n = 1), and G3 (n = 1, transurethral resection). The remaining 22 patients (57.9%) had no symptoms (CTCAE, v. 5.0) [23]. One patient required a temporary urethral catheter, and one patient developed minor (G1) rectal toxicity.

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to determine whether focal hemi-gland brachytherapy is as effective as whole-gland brachytherapy in the treatment of low-risk and favorable intermediate-risk prostate cancer by comparing the two therapies in terms of treatment failure rates and side effects.

Data on toxicity outcomes for the WGBT group were obtained from a retrospective study previously carried out at our institution [1, 25, 26]. That series included 700 patients, who underwent transperineal, ultrasound-guided 125I brachytherapy (145 Gy) between 2000 and 2012. The median age was 64.8 years (range, 35-79). Most of these patients (638/700, 91%) had low-risk disease (D’Amico criteria) and 12% (n = 85) received hormonotherapy.

Chronic GU toxicity was lower in the HGBT group compared with the WGBT group [1]. Late GU toxicity rates in the WGBT study were as follows: grade 0-1: 89.9%, G2: 9.2%, and G3: 3.3%. The most common G3 toxicity was urethral obstruction, with 17 patients requiring transurethral resection of the prostate or urethrotomy. One death (G5 toxicity, urinary sepsis) was reported.

Langley et al. carried out a clinical trial (“HAPpy” trial) with a study design similar to ours. These authors compared HGBT with WGBT, finding that HGBT resulted in lower IPSS scores, with a trend towards better erectile function [4]. In our study, the only significant difference (p = 0.002) between HGBT and WGBT was in urinary irritative-obstructive symptoms, which were lower in the HGBT group. Ta et al. evaluated toxicity outcomes in a cohort of patients treated with HGBT, showing that IPSS scores worsened at 2 months (p = 0.0003) vs. baseline, but these differences disappeared over follow-up time. The authors did not observe any late urinary or sexual toxicity [16].

Late GI toxicity was minimal in the HGBT group, with only one patient (2.6%) developing rectal toxicity (G1). By contrast, in the historical WGBT cohort, 18 patients developed late G2-3 GI toxicity (2.57%). These findings confirm no differences between the two groups in terms of GI toxicity. Conversely, Langley and colleagues observed a trend towards improved bowel QoL [4]. Also, in a French study on focal BT (Ta et al.), no late rectal toxicity was observed [16].

Quality of life outcomes were similar in the HGBT and WGBT cohorts, although worsening of the urinary irritative-obstructive symptoms was less significant in the HGBT group. Both cohorts experienced some degree of impairment in the domains evaluated (i.e., urinary incontinence, urinary obstruction, bowel, and sexual function). Interestingly, these results contrast with the toxicity results, a secondary outcome measure in this trial, which showed less impairment.

Nadir PSA was higher in the HGBT group than in the WGBT cohort, probably due to the presence of normal prostate tissue in the contralateral lobe. However, the role of PSA kinetics as a surrogate marker of treatment success in ablative focal therapies was questioned because this approach leaves the functioning prostate tissue in situ. In HGBT, the contribution of a non-tumoricidal radiation dose to the untreated hemi-gland remains undetermined. Nonetheless, PSA appears to be a valuable marker to assess disease control in this form of focal therapy [4].

Oncologic outcomes were significantly worse in the HGBT group compared with the historical cohort, with a 5-year biochemical relapse-free survival rate of 54% vs. 95%, respectively. At 5 years, the overall survival rate was slightly lower in the HGBT group (92.1% vs. 94%).

Oncologic outcomes in the HAPpy trial [3, 4] were far superior to those obtained in our study in the focal BT group. In the HAPpy trial, treatment failure occurred in 2 out of 30 patients (6.7%), while in our series, it occurred in 17/38 cases (44.7%). We believe that these differences can be explained by the systematic use of mpMRI and transperineal template biopsy in the HAPpy trial. Moreover, these authors obtained more biopsy cores in each patient, with a mean of 30 cores vs. only 10-20 in our series, depending on the referring hospital. By way of comparison, Anderson et al. reported a mean of 26 cores [15]. In addition, we did not perform any biopsies at 1 and 2 years post-treatment, even though this is the recommended approach for focal treatment [12, 13] and for focal ablative therapy [7]. It is important to note, however, that the above-mentioned studies were not published until the current trial was closed.

In addition, other authors reported better results with focal BT. Matsuoka et al. reported a match-pair analysis of 51 patients and compared them with 51 patients treated with radical prostatectomy [27]. After a median of 5.7-year follow-up, 5-year biochemical failure-free survival rate was 79%.

Two systematic reviews on focal BT were recently published. Hopstaken et al. identified 8 studies in 2022 [28]. Sample sizes were small with a median of 30 patients (range, 5-50), and a median follow-up was 24 months. Three research reported a 100% absence of clinically significant cancer in the treated area, although one study reported 12% after treatment. Treatment was well-tolerated, with only one study reporting one grade 3 complication, i.e., acute prostate hemorrhage due to incorrect catheter removal. Concerning continence, no differences for pre- and post-procedural continence scores were seen; only one study reported a significant increase in IPSS score from 8 to 14 at 6 months. Four studies reported on erectile function, with 3 presenting a decline. A second meta-analysis was published by Mohamad et al. in 2024 [29]. Ten studies were identified, including 315 patients treated with focal brachytherapy as a definitive treatment. Mean PSA was 7.15 (2.7) ng/ml. Most patients (n = 236, 75%) underwent LDR brachytherapy and 25% received HDR-BT. Among the participants, 147 (46.5%) had a Gleason score ≤ 6, and 169 (53.5%) had a Gleason score ≥ 7. Only 11 (3.5%) patients received ADT. Biochemical control rate at a median follow-up of 4 years was 91%. Late grade ≤ 2 GU and GI toxicity were reported in 6 (2%) and 14 (4.4%) patients, respectively, without any G3.

The low enrolment number in our clinical trial can be explained by several different factors. First, the European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines recommend active surveillance for these patients [30], which may at least partially explain why so few patients were referred to our hospital for BT in that period. In addition, BT is not the only focal treatment available for patients with low-risk PCa. Other forms of focal therapy, including HIFU and cryotherapy, are also used in this population. For example, Kaufman et al. treated a large series of patients (n = 91) with focal HIFU [31]. The primary endpoint of that study was failure-free survival (FFS), defined as the absence of clinically significant PCa in- or out-of-field in a protocol-mandated saturation biopsy. At 36 months, the FFS rate ranged from 44% to 65% in patients who underwent the protocol-mandated biopsy (only 51% of the sample). Even though we did not perform post-implant biopsies, the 5-year biochemical failure rate in our cohort was 40.4%, which was close to the rate reported by Kaufmann and colleagues. Marra et al. compared focal cryotherapy with active surveillance in patients with low-to-intermediate-risk PCa [32] in a group of patients treated between 2008 and 2018. In that study, 121 patients underwent focal cryotherapy, and 459 patients were under active surveillance. At a median follow-up of 85 months, the only significant between-group differences were time to radical therapy, time to radical therapy plus androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), and time to any treatment, all of which were shorter in the active surveillance group. At 10 years, the radical therapy or ADT-free rate was 51% vs. the 5-year biochemical control rate (59.6%) observed in our study. Complications were relatively rare (26.5%), and mainly low grade; three men developed incontinence, while scores on both the international index of erectile function-5 (IIEF-5) and the IPSS increased. Based on these findings, the authors concluded that despite the low complication rate of focal cryotherapy, no meaningful advantages over active surveillance were detected at 10 years, and thus active surveillance should be preferred to focal cryotherapy in this patient population.

In line with our findings, Mohamad et al. concluded in their systematic review and meta-analysis that definitive focal brachytherapy has a favorable toxicity profile, although oncologic outcomes are yet to mature. The evidence is limited by the small number of studies with a low number of patients, across study heterogeneity and possibility of publication bias [29]. Perhaps the main issue in our trial is the failure to systematically obtain key data. Ideally, all of the patients should have undergone mp-MRI, followed by a systematic transperineal mapped biopsy fused with MRI, before performing focal BT. Unfortunately, both of the participating hospitals in this study are brachytherapy reference centers, which means that most patients were referred from small hospitals in our coverage area. In fact, MRI was performed in majority of our patients after biopsy. After obtaining the results, it was confirmed that the correct staging of PCa was definitively multiparametric, while systematic biopsies of the whole prostate were directed to the suspicious lesions. Another limitation is that no central revision of the pathologic biopsies was performed, which would have provided a more standardized and reliable data.

Given the results of the present trial and in the frame of its important limitations, we recommend more research to be conducted to better determine the role of HGBT. More specifically, prospective, well-designed trials, similar to the LIBERATE prospective registry on focal LDR-BT [15], are needed. The LIBERATE study, which is currently underway in Australia, will assess local control at 18 months based on repeated biopsy and mpMRI, and will also evaluate 5-year biochemical progression-free survival [15].

Overall, the body of evidence to support focal treatment as a feasible alternative to either active surveillance or radical interventions for localized PCa is limited, as shown in the systematic review by Bates et al. [7]. Moreover, the available data on the oncological effectiveness of focal treatment vs. standard treatment options are mixed and inconsistent [7]. In this regard, Bates and colleagues concluded that there is insufficient high-certainty evidence to endorse focal treatment as an oncologically effective and durable modality for the management of localized PCa, compared with active surveillance or radical treatment. Consequently, the use of focal treatment is not currently recommended in routine clinical practice. Instead, focal treatment should only be performed in the context of a clinical trial or rigorously-designed prospective comparative study, which include comprehensive data collection, standardized definitions, and appropriate outcome measures [7].

Conclusions

The results of the present small clinical trial on focal hemi-gland prostate brachytherapy do not support this treatment modality for localized prostate cancer due to high biochemical failure and contralateral relapse rates. Moreover, biochemical and local control rates were much worse in patients who received HGBT vs. the historical cohort treated with WGBT, even though this had no impact on the overall survival. Interestingly, HGBT was associated with lower rates of chronic toxicity than WGBT, although patient-reported QoL outcomes were similar to those obtained with WGBT.

The unfavorable outcomes observed in this trial are likely attributable to sub-optimal patient selection, resulting from overly permissive and/or ambiguous inclusion criteria and inadequate diagnostic assessment. More specifically, majority of the patients were referred from small hospitals in our coverage area, and there was no central assessment of MRI or biopsy cores. In short, the data obtained in the present study do not support HGBT over standard WGBT for patients with low-to-intermediate-risk PCa. Nonetheless, based on findings from previous studies and our own clinical experience, we believe that hemi-gland brachytherapy is a promising technique that merits further research in prospective, well-designed trials with appropriate selection criteria and larger cohorts.