Purpose

Brachytherapy remains a standard treatment in many indications, including locally advanced cervical cancer, endometrial cancer (adjuvant treatment), and localized prostate cancer. Additionally, brachytherapy is the preferred technique in case of local relapse in previously irradiated areas. With general increase in the incidence of cancer and the development of new indications for brachytherapy, the number of patients requiring brachytherapy in the coming years should increase. However, brachytherapists are in short supply in brachytherapy centers. For example, while at least 3 large randomized phase III studies have shown the benefit of a brachytherapy boost for intermediate- or high-risk prostate cancers, a simulation published by the team of Nice (France) within the framework of the French Society of Radiotherapy and Oncology (Société Française de Radiothérapie et d’Oncologie – SFRO) brachytherapy group has shown that, in order to deal with new indications, each French brachytherapist trained in prostate brachytherapy would have to perform 8 implants per week in 2025 [1]. It is therefore crucial to properly train young radiation oncologists. A previous survey in 2012 assessed the state of brachytherapy training among French residents during SFJRO national brachytherapy courses. With almost 10 years of observation [2], the objective in the current paper was to update these results, and to understand the expectations of young radiation oncologists regarding their brachytherapy training.

Material and methods

As a reminder, since 2017 in France, medical studies are structured as follows: two years of theoretical courses at the faculty of medicine, followed by four years of theoretical courses associated with part-time internships in hospitals, and a national competitive examination. Students choose their university hospital of affiliation (all over France, one by administrative region approximately) and their specialty by ranking. Then, the residency period starts, which lasts 5 years for students who have chosen oncology. The residency consists of a succession of 6-month full-time hospital internships from November to May and from May to November. Residents are full-fledged physicians with the right to prescribe, but are supervised by a senior physician at all times. French regulations require oncology residents to complete a 6-month internship in medical oncology and another in radiotherapy during their first year of residency (called the ‘base phase’). At the end of the first year, the residents choose between medical oncology and radiotherapy. Then, during next 3 years (‘consolidation phase’), the resident must complete two internships in radiotherapy, one in medical oncology, two internships among a list of pre-defined specialties (radiology, nuclear medicine, pathology, etc.), and one internship in a discipline of the resident’s free choice. The last year (‘junior doctor’) must be spent at the same radiotherapy department. Internship sites are chosen by the residents every six months from a list in the administrative region, to which they are attached. Therefore, in most regions outside of Paris, only one to three radiotherapy training sites are available. To choose an internship in a department belonging to another region (inter-hospital exchange), the intern must request authorization through a long and complex administrative procedure. At the end of the residency, the intern obtains his/her diploma on the basis of the defense of his/her thesis (at the end of the 4th year), of his/her dissertation (also corresponding to a clinical research work) and on his/her assiduity during the theoretical courses and internships. Their skills in radiotherapy (and even more so in brachytherapy) are not evaluated as such. An evaluation grid with general notions that residents should master does exist, but the evaluation is mostly through multiple choice questions in e-learning and an oral examination in front of a local commission. Theoretical training of residents is at the discretion of the faculty attached to each university hospital and is therefore variable. Thus, the Association of Young French Radiotherapy Oncologists has created a series of theoretical courses, 5 days per year, every 5 years (in order to follow the classic curriculum of an intern). Two days every 5 years are dedicated to brachytherapy.

At the end of the 2021 SFJRO brachytherapy online courses, a questionnaire was submitted to all participants. It was based on the 2012 questionnaire, which was the result of a collaborative work between the SFJRO and the SFRO Brachytherapy Group. This questionnaire was updated to consider recent developments in the discipline, using relevant publications and a focus group organized with residents and fellows at the Institut Curie, Paris.

The questionnaire assessed demographic characteristics of the surveyed residents (hospital of affiliation, seniority), their interest in brachytherapy, their theoretical and practical training, and their wishes for improvement in their training. Answers were free and anonymous.

For the sake of comparison with the previous 2012 analysis [2], the seniority of residents has been classified between first and second year, third to fourth year, and more than 4th year. Since the onset of French reform of medical studies in 2017, the reflection will have to be organized around the base phase, the consolidation phase, and junior doctor (see the above).

Concerning statistical analysis, the qualitative variables were described using numbers and percentages, the quantitative variables using mean (± standard deviation) or median, and the range if the normality hypothesis was not verified. Statistical significance level was set at 5% for each statistical analysis and confidence interval. Comparisons of proportions were performed with chi-square (χ2) or Fisher tests when the expected number of participants was less than 5. Statistical analysis was done with R software.

Results

Demographics

Of 162 students registered in brachytherapy courses, 118 completed the survey (73% participation rate). Results were compared to 2012 responses corresponding to French respondents only.

Twenty-six residency regions were represented. Seniority in the curriculum is presented in Table 1. The distribution was mostly identical to the 2012 survey (p = 0.3).

Table 1

Distribution of respondents according to their advancement in their curriculum

| Advancement in curriculum | 2012 proportion (%), n = 92 | 2021 proportion (%), n = 118 |

|---|---|---|

| Beginning of curriculum | 33 | 27 |

| Middle of curriculum | 43 | 43 |

| End of curriculum | 24 | 30 |

Eighty-eight percent of the respondents had access to at least one brachytherapy unit in their region. Among the 14 residents who did not have access to brachytherapy internship in their region, the reasons mentioned were the absence of brachytherapy unit in 38% of cases, the absence of radiation oncologist practicing brachytherapy in 33% of cases, and the non-organization of brachytherapy service to receive residents in 19% of cases. The absence of operating room (5%) and of radiation protected room (5%) were less frequently cited reasons.

Of the residents who had access to a brachytherapy unit in their region, 53% reported having access to only one brachytherapy division, 20% to two units, and 27% to three or more units.

Vaginal and utero-vaginal brachytherapy were available in the region of 93% and 84% of the residents respectively. Gynecologic brachytherapy with interstitial implants was available to 64% of the residents. Prostate brachytherapy with permanent or high-dose-rate implants was available to 61% and 38% of the respondents, respectively. Techniques less frequently represented were anal canal (38%), skin tumors (38%), ENT (28%), breast (21%), intra-operative brachytherapy (13%), rectal brachytherapy (11%), pediatric brachytherapy (9%), and endoluminal brachytherapy (esophagus, bronchi) (8%). Five percent of the residents did not know what kind of brachytherapy technique was available in their region.

Interest in brachytherapy

Eighty-six percent of the respondents expressed their interest in brachytherapy compared with 91% in 2012 (p = 0.3).

The dosimetric benefit of brachytherapy, its’ interventional nature, technicality as well as its’ service to patients were the strong points identified by the respondents (70%, 69%, 63%, and 63% of cases, respectively). Compared with 2012, the dosimetric benefit and technicality were more widely cited (70% vs. 59%, and 63% vs. 43%, respectively).

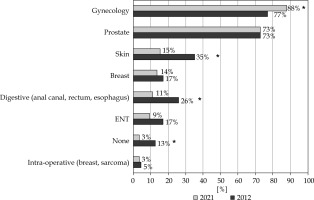

Theoretical training

The proportion of residents knowing the indications for gynecological brachytherapy was significantly higher than in 2012 (88% vs. 77%, p = 0.03), whereas it was stable for prostate brachytherapy indications (73%) (Figure 1). Less common indications tended to be less well-known: skin tumor (15% vs. 35%, p = 0.001), breast (14% vs. 17%, p = N.S.), digestive tumor (11% vs. 26%, p = 0.05), ENT tumors (9% vs. 17%, p = N.S.) (Figure 1). While 13% of the residents knew none of the indications for brachytherapy in 2012, only 3% were in this situation in 2021 (p = 0.01). The proportion that brachytherapy represents in the indications for radiation treatment in France was known by 45% of residents. Forty-one percent of the respondents did not know how to obtain useful recommendations/resources to learn on the indications and to perform brachytherapy in most common indications. The residents were interested in additional brachytherapy training, mainly the GEC-ESTRO courses (53%), the national university diploma in brachytherapy (DU) (52%), and the national brachytherapy workshops (40%).

Practical training

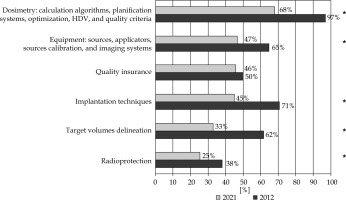

Eighty percent of the residents found their brachytherapy training insufficient compared with 81% in 2012 (p = 0.7). The distribution of untaught aspects in the training of residents in 2021 was similar to 2012, but the training has significantly improved in the meantime. Indeed, treatment planning/dose calculation was missing in the training of 97% of the residents in 2012 compared with 68% in 2021 (p < 0.0001), equipment in 65% vs. 47% (p = 0.02), and implantation techniques in 71% vs. 45% (p = 0.0007) (Figure 2).

Fig. 2

Responses to the question “What theoretical and/or practical aspects of brachytherapy have you not been taught?” between 2012 and 2021 (*significant)

Brachytherapy activities seen or practiced during residency are presented in Table 2. Between 2012 and 2021, there was a borderline increase in the proportion of residents who achieved proficiency in the vaginal vault brachytherapy technique (24% vs. 36%, p = 0.07), but other acquisitions were globally unchanged: 13% for utero-vaginal brachytherapy and 4% for prostate brachytherapy. It should be noted that only 4% of the residents had achieved proficiency in the technique of gynecological brachytherapy with interstitial implants, and 36% of them had never even seen one.

Table 2

Proportion of residents who have seen, done, or learned different brachytherapy techniques

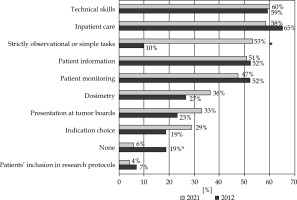

The roles of brachytherapy resident when in brachytherapy rotation in 2012 and 2021 are shown in Figure 3. Six percent of the residents reported having no role, and 12% reported having only a strictly observational role. The proportion of residents reporting having no role in their brachytherapy rotation was significantly lower than in 2012 (6% vs. 19%, p = 0.005). This year, 53% of the residents reported having an observational role in addition to other roles, likely reflecting heterogeneity between the different brachytherapy units and/or supervisors.

Fig. 3

Responses to the question “What are your roles while in brachytherapy rotation?” in 2012 and 2021 (*significant)

Sixty-three percent of the residents stated that they always had senior supervision during their internship, while 32% had supervision mainly during technical procedures, and 5% were never supervised.

For 92% of the residents, brachytherapy activity in a rotation represented 25% or less of the total rotation time and less than 5% of their total training in 68% of the respondents. These figures are comparable to the 2012 survey (p = 0.8). Forty-seven respondents (i.e., 40%) had done or wished to do an inter-hospital exchange (inter-CHU) to learn or improve their technique, 45 of whom originated from outside of Paris. At the idea of taking up a position as a fellow with brachytherapy activity at the end of their residency, 53% of the respondents declared themselves as ‘not confident’ or ‘not at all confident’.

Perspectives for improvement

The main obstacles to theoretical training were difficulty of leaving hospital duties (71%), lack of information on available courses (69%), the cost of courses (64%), and logistical difficulties in getting to various courses (61%) (Figure 4A). Residents from outside of Paris were statistically more likely to cite logistical difficulties in getting to training courses (67% vs. 37% among Parisians). On the question of an overall lack of interest in the discipline, the residents were divided: 38% agreed and 31% disagreed.

Fig. 4

Responses to the question “Apart from the current unfavorable pandemic context, what do you think are the obstacles to your training in brachytherapy?”. A) Obstacles to theoretical training; B) Obstacles to practical training

Barriers to practical training were the need to visit several centers to learn about several indications (85%), insufficient brachytherapy activity in the center to progress effectively in the time allotted to residency (72%), reluctance to invest significant time in a brachytherapy internship when the activity may not be available in the future practice site (65%), and lack of brachytherapy centers in the region (64%) (Figure 4B). Despite the availability of a brachytherapy unit, the residents reported difficulty in actually accessing brachytherapy practice in 62% of cases, especially among Parisian residents (86% vs. 56%, p = 0.008). Residents from outside of the capital seemed to be particularly disadvantaged by the limited supply of brachytherapy units: 72% of these residents cited the lack of a center in their region (p = 0.0004). The elder respondents (in their last year of training) unanimously agreed with the reluctance to train when brachytherapy may not be available in the future practice location (p < 0.01).

Residents trained in cities where a brachytherapy referral center was available did not report a difference in the adequacy of their brachytherapy training (22% vs. 19%, p = 0.8), or in the proportion that brachytherapy represented in their training (p = 0.5). However, their acquisition of techniques was significantly higher in intra-cavitary uterovaginal brachytherapy (20% vs. 7%, p = 0.02) and in breast brachytherapy (6% vs. 1%, p = 0.03).

The participants were interested in materials to improve their brachytherapy training. Educational materials perceived as the most relevant included contouring/dosimetry workshops (79%), mannequin training (70%), publications/books dedicated to residents (67%), face-to-face courses (65%), didactic videos (64%), online courses/webinars (62%), and virtual reality simulation (53%).

Discussion

The present study highlights significant progress in brachytherapy residents’ training since 2012, particularly in their knowledge on indications for gynecological brachytherapy, their competence in vaginal vault brachytherapy (36% vs. 24% in 2012, p = 0. 07), and better understanding of certain aspects of the discipline, including treatment planning/dose calculation (97% in 2012 vs. 68% in 2021, p < 0.0001), equipment (65% vs. 47%, p = 0.02), and implantation techniques (71% vs. 45%, p = 0.0007). Since the last survey, two national training courses have been made available to residents and young practitioners (national brachytherapy workshops since 2011 and national university diploma in brachytherapy since 2018). Both consist of six to ten days of theoretical courses, including mannequin practice and observational internship in a reference brachytherapy unit for three days. However, despite the efforts of brachytherapy teachers over the last ten years, there is still a progress to be made [3].

Residents’ interest in the discipline did not appear to be an issue, with 86% of the residents expressing interest and 31% not considering a general lack of interest as a barrier to training. A recently published survey among 445 radiation oncology residents from 21 countries in Europe also showed that BT teaching is of importance to them, since 60% residents considered that performing brachytherapy independently at the end of residency is very or somewhat important [4]. The SFJRO brachytherapy course was optional back in 2012 (when the first survey was made), and has been made mandatory ever since. Therefore, the views expressed in the current study are very representative of the current radiation oncology residents, since almost all of them were present at the course. However, since the course is now mandatory while it was optional back then, the views expressed in the 2021 survey are the ones of all-comers residents, while in 2012, the students attending the course were probably the most enthusiastic and probably the most trained French residents. The slightly lower proportion of residents interested in brachytherapy in 2021 compared to 2012 is likely due to this fact. In 2016, a similar survey was conducted among Canadian residents [5], which also found great enthusiasm among them, with 97% considering important brachytherapy to be integrated into radiation therapy education. Similarly, in a survey similar to ours among 145 US radiation therapy residents published in 2016, 96% of residents considered brachytherapy education important [6]. 72% of residents were encouraged by their supervisor to study brachytherapy, but only 31% reported having a structured brachytherapy educational program. However, in the United States, the access to brachytherapy for residents appears to be more widespread [7, 8] and an extensive fellowship program in brachytherapy has been developed in recent years [9].

Our survey showed that residents knew the indications for gynecologic and prostate brachytherapy in 88% and 73% of cases, respectively. It seems essential that all young radiation oncologists know the possible indications, and are confident about the efficacy of brachytherapy in order to be able to refer patients correctly to referral centers [10]. On the other hand, brachytherapy indications for skin, ENT, and digestive cancers seem to be less known by the residents. Indeed, these indications have lost popularity in France in recent years in general, despite a strong historical background of brachytherapy, given the acceptable and logistically much simpler alternatives with modern EBRT, surgery or systemic treatments. Only a handful of centers in France still perform that kind of brachytherapy. In a web survey involving 23 Italian radiation oncology schools’ directors, there was a wide heterogeneity in the learning activities available to trainees in BT across the country. Overall, the availability of different BT procedures was superior to French training programs, since, for instance, 50% of centers offered pediatric brachytherapy, 75% anal BT, 60% eye BT, and 80% endobronchial BT. While gynecologic BT was available in 95% of academic hospitals surveyed, only 59% of school directors declared it was worth teaching that to residents which is worrying for the future, since no valid alternative has proven efficacy in locally advanced cervical cancer. On the other hand, HDR prostate brachytherapy was deemed worthy of teaching by 94% of school directors [11]. Although outside of the scope of this particular survey, it would also be important to foster brachytherapy among residents of other disciplines. Certainly, the disinterest or misconception of other specialists (gastroenterologists, dermatologists, surgeons, gynecologists, etc.) in brachytherapy may also be partially responsible for the decay of brachytherapy in some indications.

The 2017 ESTRO curriculum [12] states that: “Trainees should have an opportunity to become at least familiar with brachytherapy. This can be organized by collaboration with institutions, in which these treatments are concentrated”. The Core Curriculum General Competencies include the ability to identify when brachytherapy may be of value, plan patient’s procedure, and to determine and outline gross tumor volume (GTV), clinical target volume (CTV), internal target volume (ITV), planning target volume (PTV), organs at risk (OARs), and planning organ at risk volume (PRV) using appropriate diagnostic scanning techniques, including computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET)/CT in brachytherapy planning, to evaluate brachytherapy treatment plan in collaboration with physicists and radiation therapy technologists (RTTs), to evaluate the risks and benefits of a brachytherapy treatment plan, to discuss the indications and aims of brachytherapy, to apply radiation protection principles when assessing patients, and to manage early radiation reactions in patients receiving brachytherapy. As far as France is concerned, in the evaluation grid of the specific techniques that a junior doctor must learn, brachytherapy appears along with stereotactic radiotherapy, hadron therapy, intra-operative radiotherapy, and contact radiotherapy. The aspects of brachytherapy to be mastered according to this grid are prescription, applicator/seed placement, delineation, and planification, all under complete senior supervision. These different aspects of training seem to have improved since 2012 in our study, but they still need to be taught more widely, since 68% of the respondents did not feel sufficiently trained in dosimetry, and 45% in implantation techniques. As dosimetry is performed in some centers by a physicist or dosimetrist, it may be necessary to involve these specialists in the teaching of residents.

Since the publication of Fumagalli et al. [2], brachytherapy has continued its’ technological revolution, with numerous developments in imaging, applicators, and source projectors. With the demonstration of efficacy of interstitial brachytherapy in gynecology and prostate brachytherapy boost, these procedures should be offered in clinical routine to all patients, regardless of their place of residence in France. This increase in technicality further lengthens already long learning curves. In the latest US accreditation council for graduate medical education (ACGME) program in 2019, residents were required to perform at least 15 intra-cavitary implants (vaginal vault or utero-vaginal), and 5 interstitial implants during their training [13]. An analysis of this program between 2007 and 2018 in the United States showed that the number of intra-cavity implants per resident increased from 40 to 49 (p < 0.005), while the number of prostate implants decreased from 21.5 to 12 (p < 0.001), primarily due to the overall decline in prostate brachytherapy activity over this time period [14, 15]. Experience in gynecological brachytherapy with interstitial implants remained low, on average 0 to 2 implants per resident, which was globally consistent with the results of our survey (24% of residents had done and 4% have achieved proficiency) [16]. In France, this ‘logbook’ system with quantitative targets for procedures to be performed does not exist in brachytherapy, whereas it has been introduced for other technical specialties, particularly surgery [17]. The existence of a learning curve is however well-described in brachytherapy as in surgery [18-22]. Therefore, it is crucial that residents perform a variety of brachytherapy implantations under supervision during their curriculum. Forty-six percent of the residents in our survey mentioned the lack of supervised practice as a barrier to their learning, especially when the senior physician never hands over the implantations to the resident. And yet, it has been shown by Shaikh et al. that interstitial prostate seed implants can be safely performed by trainees with appropriate supervision: in 291 patients treated with low-dose-rate permanent interstitial brachytherapy for a localized low-/intermediate-risk prostate cancer, there was no impact on V100, D90 at the prostate or on freedom from biochemical failure, when comparing the resident, fellow, or attending groups [23]. In the INTERACTS survey from Italy, the main barriers to BT education were comparable, since 63% of school directors mentioned the lack of clinical practice (63%) [11]. In the aforementioned European survey, barriers to achieve independence in BT were reported as the lack of appropriate didactic/procedural training from supervisors (47%), decreased case load (31%), and lack of personal interest in brachytherapy (18%). 68% reported their program lacks a formal BT curriculum and standardized training assessment [4].

In our study, 52% of the residents said they were ‘not confident’ or ‘not at all confident’ in performing brachytherapy during their fellowship period, which is comparable to figures published in the United States, where only 54% of residents felt capable of performing brachytherapy at the end of their residency. It is also comparable with the European survey, in which, the confidence in joining a brachytherapy practice at the end of residency was high or somewhat high in only 34% of senior residents [4]. However, the proportion of residents who mastered different techniques was much higher in the United States compared with our survey: brachytherapy of the vaginal vault was very well mastered (97% vs. 36% in our survey) as well as simple intra-cavity brachytherapy for cervix cancer (83% vs. 13% in our survey). As brachytherapy of the vaginal vault is relatively simple, this low figure more probably reflects the lack of practice by a large proportion of residents in France (no access to a rotation or no supervised practice). 66% and 46% of residents felt able to perform gynecologic interstitial brachytherapy or prostate brachytherapy, respectively, at the end of their residency in the United States vs. 4% and 4%, respectively, in our survey. Residents’ confidence in their ability to perform brachytherapy on their own was directly correlated with the number of implants performed [6]. In the European survey, in senior years of training, the only application performed more than 5 times was vaginal cylinder for post-operative endometrial cancer in 50% of responders, intra-cavitary applications for cervical cancer in 37%, interstitial applications in 23%, and prostate in 20% [4].

It is therefore more crucial than ever to organize a coherent training program for our young radiation oncologists in this discipline. Although brachytherapy training is not limited to residency, the low proportion of residents having achieved proficiency in the most frequent brachytherapy techniques remains of concern. One of the reasons frequently given by residents as a barrier to training, particularly in Paris, was the reluctance to train when brachytherapy may not be available in the future place of practice. Indeed, in France, because of the unfavorable reimbursement model in brachytherapy by the health insurance system, very few private practice perform BT [10]. However, a certain number of residents decide to join the private practice sector at the end of their residency/fellowship. As brachytherapy also requires scarce resources to be practiced correctly (operating room, anesthesiologist, imaging platform, trained radiation oncologist), the activity tends to be concentrated in large centers [24].

Another reason frequently cited as a barrier to training is the lack of activity in the center, implying that one has to go to several centers to learn the different indications, with 12% of the residents not having access to a brachytherapy unit in the region. The prognostic impact of the volume of activity in the center has been widely demonstrated in interventional disciplines (particularly in surgery) on the quality of treatments, sometimes leading to the establishment of minimum quotas of interventions per year to maintain the activity of a center. It is quite obvious that this relationship also exists in brachytherapy, and the training of residents is therefore affected. In our study, residents from cities where a brachytherapy reference center was available were better trained overall in uterovaginal brachytherapy and breast brachytherapy, even if these results are partially diluted by residents having performed inter-hospital exchanges in reference centers. This observation is not specific to France [25]. In a survey conducted in 2015 during the Indian Brachytherapy Society’s annual meeting, 93% of brachytherapists said they believed the cause of the decline of brachytherapy in India was related to the lack of training [26]. After a brachytherapy training workshop, 66% of young Indian radiation oncologists reported that the lack of expertise was the reason why brachytherapy is less and less performed [27]. Similarly, in a survey of US residents, 59% found low activity to be the barrier to acquire autonomy in discipline [6]. In fact, the analysis of the logbooks of American residents between 2007 and 2018 showed a steady decrease in the number of interstitial implants performed by residents from 34.5 to 20.6 (p < 0.001), due to decreasing prostate volume, from 21.5 to 12 (p < 0.001) [16, 28]. France has fewer brachytherapy centers per capita than other countries: one center per 1,200,000 inhabitants in France vs. one per 850,000 in Spain, for example [29]. In an analysis of radiotherapy units in Europe, it was found that France had one of the lowest rates of centers performing brachytherapy: 40% vs. 60% or more in Northern European countries, for example [30]. One of the possible ways to bypass the overall decline in activity in the country is to use simulation training on a mannequin or in virtual reality, which was favored by 70% and 53% of the residents in our survey, respectively. These modern approaches, initially developed for young surgeons, have also proven effective in brachytherapy [3, 31-34]. In India, a cadaveric ENT and gynecological brachytherapy learning workshop conducted in 2016 was a great success [27]. However, brachytherapy is best taught through a real-time training with a senior mentor. Technical teaching must not be completely disconnected from daily clinical practice, which is full of unforeseen events, but also of great richness on the human level [35].

In response to the decline in brachytherapy activity and difficulties in training of young radiation oncologists in the United States, the American Brachytherapy Society has implemented a ten-year strategic educational plan called ‘300 in 10’ [36]. The goal is to train 30 brachytherapists per year over 10 years through a multi-faceted approach (national brachytherapy curriculum, simulation workshops, two-month internship for the most advanced residents, certification process and maintenance of this certification). In Canada, a similar initiative has been developed by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada’s (RCPSC) Radiation Oncology Committee, resulting in an area of focused competence (AFC) in brachytherapy, a diploma requiring an additional year of training specific to brachytherapy [5, 37]. Beyond simple numerical objectives, a portfolio with ambitious objectives is given to the student: dosimetry, choice of indications, choice of applicator, teamwork, quality assurance, radiation protection, research, and teaching [38]. The objective in France would be to train 5 to 10 brachytherapists in full autonomy per year after the junior doctor phase and/or a fellowship, with formalization of a training contract, including periods of practical training in host departments.

Conclusions

Compared to 2012, our results confirm very encouraging signals, pushing to engage a structured and joint reflection between the French brachytherapy teachers within the SFRO brachytherapy group, the radiation oncology residents and the supervisory bodies (National College of Teachers in Oncology [CNEC], National Institute of Cancer [INCa], and Ministries of Health and Education). In the absence of a mandatory and dedicated internship in a brachytherapy expert center as in Germany or a dedicated fellowship as in North America, the residents, interested and motivated in our survey, must have a protected and assured access to brachytherapy rotations and inter-hospital exchanges.