INTRODUCTION

One of the main goals of sport science and health research is identifying independent variables (e.g., injured muscle group) that affect a dependent variable (e.g., running performance), since such information is useful for establishing predictive relationships [1–3]. Traditionally, health behaviour research has depended on regression modelling [4]. However, interpreting these interactions can be challenging, particularly when three or more independent variables are considered [4]. A more contemporary approach to this research issue involves employing machine learning algorithms [5–7]. In this regard, some authors have highlighted that machine learning represents a promising supplementary method to conventional analyses in sports injury and rehabilitation research [8], offering potential for practical research and clinical application in both primary and secondary prevention [2]. The primary concept of machine learning is to create a predictive algorithm (or model) by training on a “labelled” dataset [5, 9]. A variety of statistical techniques are employed to evaluate the significance of the effects of independent variables on the dependent variable [10]. Several machine learning models have been used in the sport science field and in the sports injury field in particular [3, 11, 12]. A systematic review and meta-analysis showed that external load metrics, as well as internal load parameters, are associated with injury risk in professional soccer players based on machine learning models existing in the scientific literature [12]. Nonetheless, when the injury occurs, there are no previous studies using machine learning approaches explaining the changes in key performance metrics through different injury types (e.g., different absence time, involved tissue). This is especially important in muscle injuries given the variability of absence times [13–15]. Return to play following muscle injuries depends on the dimension of the injury as well as the affected tissue, with more tendon involvement usually leading to longer periods of recovery [15–18].

Despite a reduction in overall soccer injury rates in recent years, muscle injury rates have remained constant [19]. This is even more concerning given that muscle injuries present a high recurrence rate [20–23], with longer associated absence periods [20, 22]. Specifically, the hamstrings are the most injured muscle group [22, 23], with one systematic review highlighting that the recurrence rate could be up to 68% [24]. Some studies have shown the impact of injuries in different cohorts, with one study showing significant reductions in playing time, jogging and running distances following injuries without specifying the injury location [25]. Another study [26] also analysed the changes in external load parameters after all-type injuries, showing a significant decrease in maximum speed reached during matches. There are only three studies revealing the effects of specific muscle injuries on match running performance. One of them showed significant reductions in distances covered at high intensities and in explosive distance following rectus femoris injuries [27]. The other two studies assessed changes in external load metrics after hamstring injuries, revealing reductions in maximal speed, highspeed running (HSR) distance and sprinting running distance [28, 29]. However, no previous studies have specifically analysed the impact of absence time on this loss of performance, which could be an important variable since the lack of competitive stimulus (e.g., substitutes) is an important factor for decreasing performance [30]. Moreover, the consequences of calf and adductor injuries for match running performance have not been studied. Understanding the key variables that explain running performance decreases could be of interest for practitioners to focus the rehabilitation on those abilities related to the actual decline in performance. Some authors have emphasized this approach, suggesting that rehabilitation should not only aim for return-to-play (i.e., the ability to fully participate in team sessions and competitive matches) but also include a return-to-performance objective. This latter goal involves achieving pre-injury levels in key performance metrics, such as high-intensity actions (e.g., sprinting, HSR) [31, 32]. Consequently, the aim of the present study was to analyse how absence time explains the loss of performance in LaLiga elite soccer players following muscle injuries. Specifically, based on external load parameters and demographical information, this study aimed to analyse the relationship between absence time and loss of performance in the main external load metrics in elite soccer players.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

A total of 110 injuries from 90 male players who competed in the First Division of the Spanish Professional Soccer League (LaLiga) during the season 2022–2023 were collected for this study. Following previous procedures [25], four pre-injury and four post-injury matches were selected for analyses. Those players who did not present pre-injury or post-injury data were discarded. This resulted in 880 match observations for each variable. For inclusion, the injury must have been confirmed in a medical report or at least through the club’s official media. Goalkeepers’ injuries were not considered due to their very different game demands in terms of match running external load [33]. Lower-limb acute muscle injuries were considered for inclusion. If the medical report specified that the injured tissue was the tendon without involvement of the muscle tissue, it was not considered due to the substantially longer absence times for these injuries, as well as due to the very different biomechanical implications [15–17]. LaLiga authorized the use of data regarding match demands for this study, and, in accordance with LaLiga’s ethical guidelines, this investigation does not include any information that identifies individual soccer players.

Procedures

The impact of muscle injuries on soccer players was analysed through a retrospective design collecting the injuries occurring during the 2022–2023 season. Two authors (JP and DM-T) independently collected the injured players, the date of the injury (i.e., date of official report), the date of return to play (i.e., date of the first match in which the player was available for competing again) and the affected muscle group (i.e., hamstrings, quadriceps, calf or adductors). When a player suffered a re-injury, it was differentiated in the anonymized codes. Then, two authors (AF-M and GR-P) confirmed the data extraction and removed duplicates. Once the information about the injured players was fully collected and confirmed, LaLiga provided data for external load parameters for the four pre-injury matches and the four post-injury matches. Finally, main outcomes were introduced for analyses.

Main outcomes

The following demographic variables were considered for analyses:

– Injured muscle group: Categorized as 1) hamstrings, 2) adductors, 3) quadriceps, 4) calf, 5) other.

– Main position of the player in the field.

– Changes in position: This was categorized as yes/no. A player was categorized as yes if his position substantially changed throughout the season (e.g., from centre back to full back) due to the demonstrated significant differences in external load demands between positions [34–36].

– Ranked position in the classification of the team in which the player competed.

– Tier (i.e., from 1 to 4, dividing the 20 competing teams into groups of 5 teams) of the team based on the classification during the 2022–2023 season.

– Number of re-injuries represented during the season for each analysed injury.

The following match running variables were considered for analyses for each match, based on previous studies assessing external load metrics from LaLiga players [37–40]:

– Number of accelerations and decelerations, regardless of the intensity (n)

– Total distance covered (m)

– Distance covered accelerating > 3 m/s2 (m)

– Distance covered decelerating < -3 m/s2 (m)

– Number of absolute HSR (21–24 km/h) actions (n)

– Distance covered at absolute HSR (m)

– Number of relative HSR (> 75.5% of the player’s maximum speed based on the WIMU profile) actions (n)

– Distance covered at relative HSR (m)

– Maximal acceleration registered (m/s2)

– Maximal deceleration registered (m/s2)

– Maximal speed registered (km/h)

– Distance covered sprinting (> 24 km/h)

– Number of absolute sprints (> 24 km/h) performed

– Number of relative sprints (> 85% of the player’s maximum speed based on the WIMU profile) actions

– Time played (min).

In addition, a composite index based on the acceleration-specific performance (component 1), high-intensity running-related variables (component 2), and medium intensity action variables (component 3) were also considered for analyses [41]. This composite index summarizing the match running performance was calculated following previously established procedures based on three latent components [41]:

Latent component 1i= −0.88 × Count of accelerations (zone 2–3 m/s2) − 0.06 × Count of accelerations (zone 3–4 m/s2) − 0.01 × Count of accelerations (zone 4–5 m/s2) + 0.04 × Count of accelerations (zone 5–6 m/s2) + 0.07 × Count of decelerations (zone 2–3 m/s2) + 1.44 × Explosive distance − 0.15 × Count of actions (zone 6–12 km/h)

Latent component 2i = −0.04 × Count of actions (21–24 km/h) + 0.13 × Count of actions (> 24 km/h) + 0.94 × Time spent (zone 21–24 km/h)

Latent component 3i = 0.10 × Average speed (km/h) − 0.49 × Count of actions (zone 12–18 km/h) + 0.23 × Count of actions (zone 18–21 km/h) − 0.01 × Time spent (zone 18–21 km/h) − 0.04 × Energy expenditure − 0.33 × High-metabolic load actions + 1.11 × High-metabolic load distance

Raw composite indexi = 0.29 - Latent component 1i + 0.39 - Latent component 2i + 0.35 - Latent component 3i

Statistical analysis

For each performance metric, two aggregate variables were created: a pre-injury average and a post-injury average, calculated as the mean across the four pre- and post-injury matches, respectively. A difference variable was also computed to capture the net change between the post- and pre-injury averages for each metric. To determine whether these pre- and post-injury differences were statistically significant, the normality of each parameter’s difference distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, with a significance level of α = 0.05. For metrics where normality was confirmed, a paired t-test was applied to compare pre- and post-injury averages; otherwise, the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used. Only parameters showing statistically significant differences between pre- and post-injury averages were included in subsequent machine learning analyses.

Machine learning analysis

The aim of this machine learning analysis was to examine the relationship between absence time (days away from competition) and the magnitude of performance changes across parameters that showed statistically significant differences between pre- and post-injury averages. Players with missing data were excluded to ensure complete datasets for analysis. All variables were then scaled to normalize each feature’s distribution. The dataset was divided into training (80%) and testing (20%) subsets via random sampling.

Two regression models were employed to investigate potential relationships between performance changes and absence time: multiple linear regression (MLR) and random forest regression (RFR), supplemented by Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP). MLR predicts a single dependent variable based on multiple independent variables through a linear relationship, providing direct interpretability due to its reliance on a linearity assumption [42], since regression coefficients directly reflected each variable’s association with absence time, with larger coefficients indicating stronger relationships. However, MLR is limited in modelling complex, non-linear interactions among features [43]. To capture non-linear relationships, a random forest model was also implemented. RFR, a decision tree-based approach, divides samples into homogeneous groups through successive queries on each variable, thus minimizing within-group variance [44]. Unlike MLR, RFR does not rely on assumptions about data distribution, making it well suited for analysing diverse, complex datasets [45, 46]. However, its “black box” nature can limit interpretability, despite strong predictive power [47]. To address this interpretability challenge, we employed SHAP, a technique that quantifies the contribution of each input variable to the RFR model [48]. SHAP values measure a feature’s importance by comparing the model’s predictions with and without that feature, effectively providing an additive feature attribution method that enhances model interpretability [49, 50]. Thus, in RFR, SHAP values highlight the magnitude and direction of each feature’s relationship with absence time, identifying the performance changes most strongly associated with absence time.

Model performance was evaluated through mean square error (MSE) and the coefficient of determination (R2) on the test data [46]. MSE quantified the model’s predictive error, while R2 indicated the proportion of variance in absence time explained by the changes in performance variables. A linear regression model was constructed to analyse the relationship between absence time (in days) and changes in the variable showing a stronger association with absence time based on machine learning models (i.e., maximal speed). The absence time was treated as the independent variable, while the maximal speed change served as the dependent variable. Confidence intervals (95%) for the regression line were included to provide an estimate of the precision of the model.

All machine learning analyses were conducted in Python, using libraries such as ‘scikit-learn’ (https://scikit-learn.org/) to streamline data pre-processing, feature selection, and model implementation.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

The dataset included 110 injuries from players who competed in La Liga, with observations for various performance metrics recorded in both pre- and post-injury matches. Table 1 summarizes key descriptive statistics. The mean number of days players were away from competition due to injury (i.e., absence time) was 34.6 ± 27.9. Muscle injuries were categorized as hamstrings (n = 51), quadriceps (n = 12), calf (n = 18), adductors (n = 12) and other lower limb muscle injuries (n = 17). Across all performance metrics, pre- and post-injury averages were calculated, along with their standard deviations (Table 1).

TABLE 1

Descriptive data for pre- and post-muscle injury main external load metrics

Pre- and post-injury differences

To assess whether the differences between pre- and post-injury performance metrics were statistically significant, we first evaluated the normality of each metric’s difference distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test (α = 0.05). For metrics with a normal difference distribution, a paired t-test was applied, while the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for metrics that did not meet the normality assumption. Table 2 provides an overview of the statistical test results for each metric, indicating significant differences between pre- and post-injury averages.

TABLE 2

Statistical test results for pre- and post-injury differences

Metrics showing significant pre- and post-injury differences (P < 0.05) included time played, total distance covered, maximal acceleration, maximal deceleration, number of relative sprint actions, maximal speed, distance covered sprinting, and the composite index. These results suggest that these parameters were meaningfully impacted by injury, warranting further analysis in relation to absence time.

Correlation analysis with absence time

To explore the relationship between absence time and performance changes, variables that showed statistically significant differences between pre- and post-injury averages were included in a correlation analysis. Table 3 presents the correlation coefficients between absence time and each significant performance metric difference.

TABLE 3

Pearson correlation coefficients between recovery time and significant pre-post performance metric differences

The strongest correlation was observed for the difference in maximal speed (r = -0.355), indicating that longer recovery times were associated with a more pronounced reduction in maximum speed. This was followed by the difference in time played (r = -0.328) and the difference in maximal acceleration (r = -0.303), suggesting that extended recovery durations are linked to decreases in both playing time and maximal acceleration. Additional negative correlations were found for the difference in composite index (r = -0.218) and the difference in the number of sprints with relative threshold performed (r = -0.149), pointing to declines in composite performance and relative sprint counts as absence time increases. In contrast, positive although weaker correlations were found for the difference in the distance sprinting (r = 0.205) and the difference in maximal deceleration (r = 0.185). Overall, these findings suggest that extended recovery times tend to correlate with reductions in high-intensity performance metrics, particularly in maximum speed and acceleration, highlighting areas most impacted by prolonged absences.

Machine learning analysis

To further understand and model the relationships between those performance metrics that seem to worsen as the recovery period extends, a machine learning analysis was conducted. While statistical analysis highlighted significant differences between pre- and post-injury performance metrics, machine learning allows us to identify and quantify the features most associated with the length of recovery time. Two distinct regression models were employed to assess the relationships between the change in performance metrics and recovery time: MLR and RFR. The MSE and R2 scores for both models on the training and test sets are presented below:

– MLR MSE: Training set = 689.057; Test set = 365.1421

– RFR MSE: Training set = 514.169; Test set = 312.355

– MLR R2: Training set = 0.1163; Test set = 0.348

– RFR R2: Training set = 0.341; Test set = 0.442

The RFR model demonstrated a lower MSE and higher R2 score compared to the MLR model, indicating better performance in capturing the relationships between performance change and recovery time. This improvement in RFR’s performance is likely due to its ability to model complex, non-linear relationships among the features, whereas MLR assumes linearity and independence among predictors. In this case, the independent variables may not be entirely independent, negatively affecting the MLR’s accuracy.

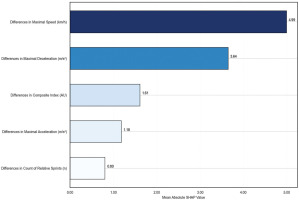

To interpret the models, Figure 1 presents a visual representation of the MLR coefficients for each variable, sorted by absolute value. This helps to identify which variables are most strongly correlated with recovery time. The MLR model estimates the absence time using the following linear equation:

FIG. 1

Multiple linear regression coefficients, indicating the relative impact of each parameter on the duration of absence.

Absence time [days] = β0 + β1 · Differences in Maximal Acceleration + β2 · Differences in Maximal Deceleration + β3 · Differences in Number of Relative Sprint Actions + β4 · Differences in Maximal Speed + β5 · Differences in Composite Index

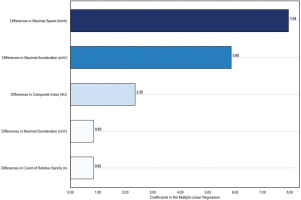

In this model, the β coefficients represent the estimated change in absence time for each unit change in the respective independent variable, assuming all other variables remain constant. β0, β1, β2, β3, β4 and β5 showed a value of 33.22, -5.85, -0.83, 0.82, -7.94 and 2.35, respectively. For the RFR model, SHAP values were used to determine the contribution of each feature to the prediction of recovery time, as shown in Figure 2. Both models consistently identified the difference in maximal speed as a key factor related to recovery time, suggesting that this metric may be particularly affected by longer recovery periods. Linear regression with 95% confidence interval of maximal speed (i.e., as the variable with better association with absence time in machine learning models) was plotted both in relative (%) and absolute (km/h) changes in Figure 3.

DISCUSSION

The effect of absence time on loss of performance

This study aimed to explain which differences in external load metrics are more strongly associated with absence time in elite soccer players after muscle injuries. Our results, derived from machine learning algorithms, suggest that absence time is associated with the loss of maximal speed, with longer absences leading to greater performance losses in this metric during matches. The results of the present study could be important to better understand what the consequences of a muscle injury are depending on its absence time. Practitioners can expect a larger decrease in maximal speed and deceleration/acceleration outcomes when the recovery process is longer, thus adapting their reconditioning strategies to perform better in subsequent matches. Given this fact, two players with a hamstring injury but differing prognoses should follow distinct return-to-play pathways. The player with a longer recovery period is likely to experience greater losses in maximal speed and acceleration/deceleration abilities during matches. Consequently, return-to-play criteria for this player should prioritize specific tests to ensure recovery of pre-injury levels of maximal speed and acceleration/deceleration [51]. These assessments should play a more prominent role in their rehabilitation process compared to a player with a shorter recovery timeline [51–53]. By adopting this approach, practitioners can optimize the rehabilitation process, facilitating quicker return-to-performance by ensuring the athlete regains pre-injury performance levels as efficiently as possible.

The loss of performance after muscle injuries has been previously reported. In line with our results, two studies showed reductions in maximal speed [26, 28]. Nonetheless, this information was not linked to the implicit variability in absence time related to muscle injuries. Our results clearly showed that maximal speed is the variable that is more closely linked to longer absence times, while maximal acceleration and deceleration can also be influenced by absence time. Interestingly, the difference in the number of sprints at the relative threshold (i.e., 85% of the player’s maximum speed) was the variable that showed the weakest relationship with absence time in our two machine learning models. This means that longer periods of recovery are not necessarily linked to greater loss of performance in this metric, so practitioners can expect similar decreases in the number of sprints performed regardless of the absence time. Nonetheless, practitioners should assess whether an athlete’s maximal speed and acceleration/deceleration capacity have returned to pre-injury levels. The composite index shows that the overall performance of the player is affected by muscle injury, but this decrease could be partly explained by the shorter duration of time played, as shown in our pre-post injury difference analyses. However, it seems that the longer the absence time, the greater the loss of overall performance (i.e., composite index), which is important to note.

Loss of performance during matches: implications and solutions

Decreases in maximal speed, maximal acceleration/deceleration, overall performance (i.e., composite index) and number of sprints were observed in our analyses. Notably, most of the recorded injuries (52 out of 110 injuries) affected the hamstrings. Maximal speed is the variable that demonstrated the largest decrease with longer absence times, which is closely related to the activity and function of the hamstrings [54–56]. Therefore, as previously reported, practitioners should check whether maximal sprinting velocity has been recovered in analytical tests (i.e., isolated linear sprints) [57, 58]. Nonetheless, previous research has established that previously injured players showed decreases in the acceleration phase (i.e., ability linked to maximal horizontal force production) rather than in the maximal speed phase [59, 60]. However, our results explicitly demonstrated that maximal acceleration ability is affected during matches, and that absence time largely explains the loss of performance in this metric (i.e., longer recovery periods lead to larger decreases in maximal acceleration). As shown in Figure 3, linear regression models clearly illustrate the downward trend in maximal speed differences as absence time increases. However, it is notable that variability also increases with longer absence periods, making changes in maximal speed more unpredictable with extended recovery times. Therefore, coaches should be particularly aware of this variability, especially in cases of prolonged absences due to injury, which often involve tendon tissue and present greater challenges for prognosis [52, 53]. Although the literature in this field is still scarce, lower acceleration could lead to less achievement of maximal speed during matches, since sprints in soccer are mainly performed for shorter distances (i.e., 2 to 4 s or 10 to 30 m) than those covered to assess mechanical sprinting properties (i.e., 40 m) [59, 60]. Therefore, given the short distances where sprints occur in soccer and given the reduced time for performing them, a loss of maximal acceleration could be linked to a reduced maximal speed outcome during matches (i.e., there is no time and space for achieving maximal speed). Given this association, it is crucial for practitioners to assess mechanical properties of sprinting prior to return to play [61]. However, it is also important to note that most of the sprints in soccer are not in a linear pattern (i.e., approximately 85% of maximum velocity manoeuvres involve curvilinear sprints) [62, 63], with torso rotation (62% of sprints) [62] and ending with an action such as duelling with an opponent or involvement with the ball (50% of the sprints) [62]. Therefore, it is important to achieve peaks of maximal speed and accelerations in integrated soccer tasks such as transition games [64], one-on-one transition tasks [65] or small-sided games [66, 67]. Regarding assessment of specific sprinting patterns in soccer, it is important to assess curvilinear sprinting tests [68] and repeated sprinting ability, recreating the specific demands of the game [69]. In addition, Global Positioning System (i.e., external load) metrics should be checked during late stages of the rehabilitation process to ensure that preinjury maximal speed and acceleration/deceleration output has been reached [70, 71].

The fact that maximal deceleration has been identified as the second most modifiable variable depending on absence time in our RFR model is highly relevant. This could be attributed to the longer absence time in those muscle injuries that mostly involve the tendon [18, 52, 53]. It is well known that high-intensity braking actions are highly dependent on the tendon capacity [72, 73], which is linked to the eccentric muscle contraction capacity [74, 75]. Based on our machine learning models and in these associations, it is crucial to check eccentric strength ability, as well as integrating it into high-demanding braking on-field activities before returning to play after muscle injuries [72]. The fact that maximal deceleration ability is more affected by longer rehabilitation processes could be associated with maladaptation in tendon capacity due to the lack of mechanical stimulus [76, 77]. Therefore, this is especially relevant in those injuries affecting more tendon tissue (associated with longer absence times). The loss of maximal braking ability is also linked to increased knee joint mechanical loading during the final foot contact of changes of direction [78]. Therefore, longer muscle injuries can potentially increase the risk of knee injuries if the loss of maximal deceleration during matches is produced due to an incapacity in reaching high-intensity deceleration values, especially after hamstring injuries [79]. Consequently, it is crucial to check maximal deceleration ability before the return to play to avoid severe injuries in other tissues such as the anterior cruciate ligament [79]. A potential solution for this issue is to introduce early eccentric exercises, which have been demonstrated to be safe during rehabilitation of muscle injuries [80]. In addition, flywheel resistance training during rehabilitation and especially braking in the last third of the movement (i.e., lengthening position) could be of interest in longer rehabilitation periods produced by tendon tissue involvement [81, 82].

While maximum speed, acceleration, and deceleration capacity are significantly influenced by absence time, our machine learning models show that the number of sprints performed is not dependent on the recovery time. This finding was surprising given that both repeated sprint ability [83] and maximal eccentric strength [84] have not been found to be impaired after injury. Therefore, the cause of the lower number of sprinting actions is not clear in our opinion. Anyway, this outcome should be checked regardless of the absence time, since shorter recovery periods can produce similar decreases in the number of sprinting actions performed. In this regard, Whiteley et al. [29] proposed that there may be additional return to sport criteria for some players in terms of high-speed running or sprinting, which aligns with the results of our study. Moreover, the shared decision-making model of return to sport highlighted the “ability to perform” [85], which is not being met based on the findings of the present study. Consequently, practitioners should consider not only clinical outcomes for avoiding reinjuries but also performance-based metrics such as the ability to perform several sprints, independently of the absence time. This aligns with the return-to-performance approach, which emphasizes not just medical clearance but the full restoration of key physical capacities essential for optimal soccer performance [31, 32].

Clinical recommendations

This study emphasized the importance of assessing the following outcomes as criteria for return to play, especially as the length of absence increases.

Ability to reach similar pre-injury maximal speed

Ability to perform similar pre-injury maximal decelerations

Ability to perform similar pre-injury maximal accelerations.

In addition, regardless of the absence time, it is always important to check:

Ability to perform similar pre-injury sprints during matches or in integrated soccer-specific tasks.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings of the present study suggest that prolonged recovery times after muscle injuries are associated with reductions in maximum speed and acceleration/deceleration capacity in elite soccer players. However, the number of sprinting actions did not show relationships with absence time, suggesting that this outcome should be assessed regardless of the recovery time. By focusing on these high-impact performance metrics during rehabilitation and taking absence time as an important factor for individualizing return to play criteria and rehabilitation progression, practitioners may be able to develop targeted interventions that expedite recovery and mitigate performance losses after injury. These findings can contribute to the design of the return-to-performance phase, helping to bridge the gap between return-to-play and full restoration of pre-injury performance levels.